Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022 came as a surprise to many Western observers and policymakers. This was perhaps based on the belief that more than three decades of transition since the fall of the Berlin Wall and the dissolution of the Soviet Union would have ended this type of aggression in Europe.

To people in Georgia (who saw Russia invade their country in 2008), to people in Ukraine (who witnessed the annexation of Crimea in 2014 and war in Eastern parts of their country), to people in Moldova (who live with the Russia-supported territory of Transnistria within their country), and to most others that live in countries that were once incorporated in the Soviet union, this was less of a surprise. The transition that started in 1989 is far from finished in many of the countries that came out from under the oppression of the Soviet Union’s communist regime.

For scholars that focus on this region, it has long been clear that the transition process from autocratic, communist, planned economic systems to open, democratic, rule-of-law-based, market economies still has some way to go. Progress has been very uneven among the countries that came out of the Soviet Union and the communist bloc in Europe. However, this progress is highly correlated with how countries have chosen to move their institutions and focus towards the EU rather than Russia. In this contribution, I will outline this in some detail and argue that a successful Ukraine entering the EU can trigger a new wave of transition not only in Ukraine but across the region, to the benefit of all of Europe’s citizens and beyond.

The transition towards liberal democracy

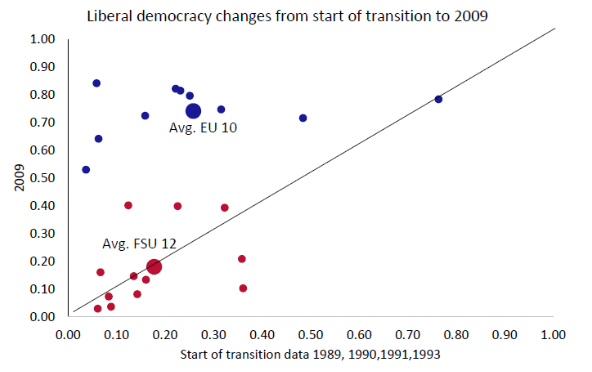

The start of transition after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the independence movements in the Baltics, and then the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 set off a first wave of transition to liberal democracy in the region. Although this transition was very different across countries, there is a very strong correlation between the transition and becoming a member of the EU (Figure 1, from Becker 2019). Two decades after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the average transition country that had become a member of the EU (‘EU10’ in Figure 1) had improved its liberal democracy score, as measured by the V-Dem project, from around 0.25 to above 0.7. During the same period, the twelve countries that came out of the Soviet Union and did not become EU members (‘FSU12’) had stayed at a liberal democracy score of around 0.2. There is of course significant variation within the groups, but regardless of the starting point, all of the countries in the EU10 group ranked well above all of the countries in the FSU12 group. In some countries, the starting point is part of the explanation, but this explanation is not valid for the majority of countries.

FIGURE 1 THE TRANSITION TO LIBERAL DEMOCRACY: THE FIRST 20 YEARS

Source: Becker (2019) based on data from V-Dem project.

Figure 1 does not provide a causal link between EU membership and the development of liberal democratic systems. However, it is clear that countries’ choice to move towards the EU and away from Russia’s sphere of influence is highly correlated with significant reforms of these societies. It is also clear that when Ukraine wanted to follow this path towards the EU, Russia found it so threatening that it first invaded parts of the country and then launched a full-scale war.

Human dimensions and the fight for dignity

As economists, it is easy to focus on economic variables in the transition process. In Becker and Olofsgård (2018), we look, for example, at how growth has evolved over time in the same groups of transition countries that are shown in Figure 1 above. There we noted that the FSU12 group of countries were further behind the EU10 at the end of the first 25 years of transition because the initial decline in incomes were so severe in the FSU 12 group that the commodity price boom later was not enough to compensate for this initial economic disaster. We also document how investments in EU10 countries are significantly higher than in FSU12 countries, but that also this can be dwarfed by external factors such as changing oil prices when we look at growth over a decade or two.

However, we know that over the longer term, relying on favourable external factors is a poor substitute for creating an environment that can deliver sustainable growth for generations to come. This is why institutions and building human capital are so critical in any fundamental transition process, and this region’s development is a testament to this. When we broaden our scope to include other variables that are critical for the wellbeing and happiness of people, the gap between countries that moved closer to the EU compared with those that did not becomes even starker. In Becker (2014), written at the time of the Russian invasion of Crimea, I showed several indicators of what it was people in Ukraine were fighting for in the Revolution of Dignity. Back then, I wrote: “…the real issue is if people in Eastern partnership countries want to live in modern, democratic, and transparent countries or in less open societies where most of the benefits accrue to ruling elites. These different social models are correlated with significant differences in a long list of indicators that are related to the well-being and happiness of people…”.

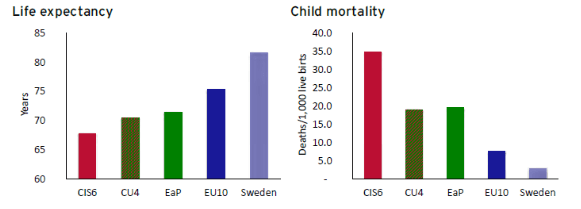

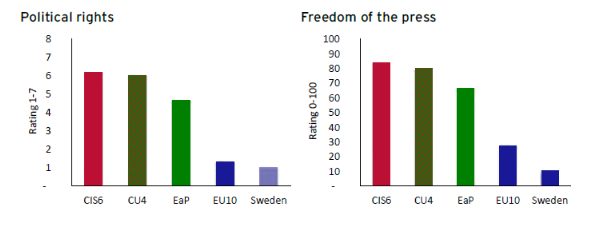

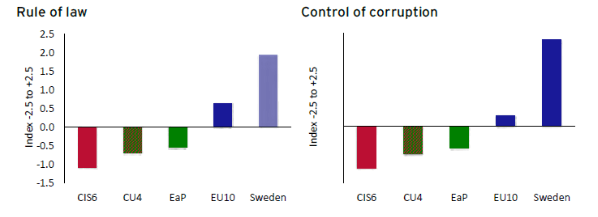

Some of these indicators are shown in Figures 2-4.

FIGURE 2 HEALTH INDICATORS

Note: the EU10 is defined as above while CIS6 consists of Russia, Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz republic, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan; CU4 includes Russia, Kazakhstan, Belarus and Armenia, members of the customs union set up by Russia as an alternative to free trade in the EU; and EaP are the Eastern Partnership countries at the time with Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine. Sweden is included since it is the EU country that is home to the Stockholm Institute of Transition Economics, which I head

Source: From Becker (2014) based on UNDP and IHME data.

Leading long, healthy lives and seeing your children survive are important factors for the wellbeing and happiness of most (Figure 2). Being able to vote in free and fair elections, being represented in political processes, and having access to media that can report on all issues that are relevant to you also contribute to a sense of meaning and dignity (Figure 3). Access to a legal system that is unbiased in providing justice and public officials that are there to serve citizens rather than themselves and their superiors are also important factors contributing to both dignity, human rights, and prosperity in a country (Figure 4).

FIGURE 3 FREEDOM INDICATORS

Note: A lower rating is better.

Source: From Becker (2014) based on Freedom House data

FIGURE 4 RULE OF LAW AND CORRUPTION INDICATORS

Source: From Becker (2014) based on World Governance Indicators data.

It should not have come as a surprise that people in Ukraine would rather move in the direction of the EU than the customs union with Russia back in 2013. What seems to have surprised Russian leaders as well as many outside observers was that people in Ukraine were ready to sacrifice their lives in the Revolution of Dignity to achieve these freedoms. It is the duty of the EU and its partners to make sure this fight for dignity was not in vain.

Finishing the transition process with Ukraine’s victory

The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 set off a first significant wave of transition from autocratic, communist systems towards liberal, democratic, market systems across the region. However, many countries that came out of the Soviet Union remain stuck in transition and have not managed to move close enough to various EU standards to allow them to join the Union.

The victory of Ukraine will not only pave the way for the citizens of Ukraine to join the EU but will also set an example for many other transition countries that got stuck on the way to membership. This could include not only Moldova, which is already a candidate country, but also Georgia, other countries in the Caucasus and Balkans, and perhaps also Belarus once it is freed of its Russian shackles and its own dictator. The road away from Russian domination and into the Union is not only the road to economic freedom, but also the road to longer and happier lives for the citizens of the countries that join in the wake of Ukraine’s victory over its long-time oppressor. It is also a transition that will make all of Europe safer, more prosperous, and happier as our region is finally freed from the last remnants of Soviet repression.

References

Becker, T (2014), “EU’s Eastern Partnerships—The real deal”, SITE Policy Paper, March.

Becker, T (2019), “Liberal Democracy in Transition – The First 30 Years”, FREE Policy Brief, October.

Becker, T and A Olofsgård, (2018), “From abnormal to normal: Two tales of growth from 25 years of transition”, Economics of Transition 26(4): 1–32.

#helpUkraine_helptheWorld

This publication is a part of a collection of essays initiated by the National Bank of Ukraine. Famous economists, political scientists and historians, experts recognized in the world, volunteered to share their thoughts and arguments on why helping Ukraine is helping the world. The complete book of essays can be found via the link.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations