In Ukraine, new legislation on personal data protection is being prepared. What will change?

Internet banking, online services, the state in a smartphone, smart homes, and smart cities. Obtaining social assistance, processing pensions or subsidies, filing declarations — all of this can now be done online without leaving home.

However, how often do citizens carefully read the Terms of Personal Data Processing Consent they sign, leaving information about themselves? And what happens to the information about each of us afterward?

Until 1991, during the Soviet Union period, the issue of personal data protection was not clearly defined. There were specific rules and provisions regulating information processing about citizens (e.g., regulations regarding record-keeping).

The state tightly controlled the processing of information about citizens. Citizens had no rights regarding their personal data.

The Constitution of the USSR formally protected certain aspects of personal life, such as the right to privacy of correspondence and telephone conversations, guaranteeing the right to personal inviolability (however, these rights were often violated by state authorities).

Starting from 1991, the Constitution of Ukraine (and later the Constitution of 1996) guarantees citizens’ right to personal and family life inviolability, including protection against disseminating information about their personal lives without their consent.

In 1992, the Law on Information laid the foundation for further protection of personal data by prohibiting the use and dissemination of information about citizens without their consent.

Overall, changes in the personal data protection system were prompted by the rapid growth in the volume of information and, as a result, the need for storage, processing, and protection.

With the emergence of a large amount of data, their computer processing, and the development of the Internet, in 1981, the Convention 108 (later updated to Convention 108+) for the Protection of Individuals concerning Automatic Processing of Personal Data was adopted.

The next step in personal data protection was the adoption of Directive 95/46/EC. In 2018, aiming to protect the rights of citizens in processing their information and its free movement between countries, this Directive was replaced by Regulation 2016/679 on data protection (GDPR), which today serves as the main document in this area.

In 2010, Ukraine’s Parliament ratified Convention 108. To implement it along with other EU Directives, it adopted the Law “On Personal Data Protection,” which defines the rules, rights, and obligations of those who provide, collect, store, transmit, process, and protect information and personal data.

However, both the methods of data processing and the regulation of data usage are constantly changing. Therefore, with changes in European norms, Ukrainian laws also require adaptation.

After Ukraine obtained candidate status for EU membership in 2023, harmonizing legislation in personal data with European Directives became even more urgent.

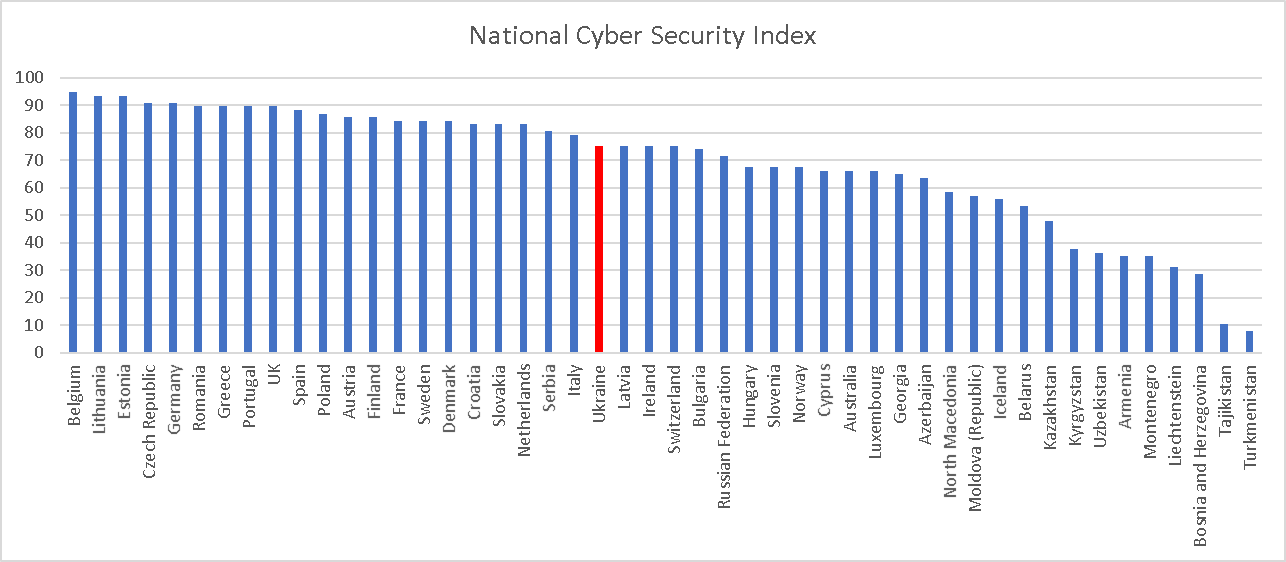

For example, in the National Cyber Security Index (NCSI) rankings in September 2023, Ukraine ranked 24th out of 176 countries worldwide and 22nd among European and former CIS countries (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Data source: e-Governance Academy Foundation

Note: The National Cyber Security Index (NCSI) is a global index that measures countries’ readiness to prevent cyber threats and manage cyber incidents. It includes 12 subcategories (such as cyber threat analysis and awareness raising, personal data protection, and military cyber defense) and covers 49 indicators.

To catch up with the level of data protection in European countries, Ukrainian parliamentarians have developed draft laws No. 8153 and No. 6177. The first proposes a new version of the Law “On Personal Data Protection.” It will regulate citizens’ relationships, rights, and obligations, as well as those to whom personal data is transferred and those who will process it.

Additionally, it provides for establishing an independent supervisory authority on personal data protection (as per EU norms). The details of establishing and operating such an authority — the National Commission for the Protection of Personal Data and Access to Public Information — are outlined in draft law No. 6177.

Currently, these functions are performed by the Commissioner for Human Rights. However, cybersecurity experts note that they cannot respond to all data breaches and losses on time.

People’s deputies propose that the National Commission for the Protection of Personal Data and Access to Public Information oversee compliance with legislation on personal data protection, handle complaints from data subjects regarding violations of their rights, and impose fines on violators.

Additionally, the Commission will review complaints regarding denying access to public information and issue mandatory decisions on providing public information that must be complied with.

From 2011 to 2014, the supervisory authority in personal data protection was the relevant state service. It was abolished to bring Ukrainian legislation in line with the International Convention 108, which stipulates that supervisory bodies can be either a single authorized person or a collegial body but not an entity subordinate to the Cabinet of Ministers.

After all, such a supervisory body should be independent and have sufficient powers to fulfill its duties.

What changes are proposed in the sphere of personal data protection?

Detailing existing norms. Draft bill No. 8153 is much more detailed than the current law, outlining the rights and obligations of data subjects (individuals to whom the data belongs), controllers (referred to as owners in the current law, meaning individuals who determine the purposes of data processing), and processors (referred to as handlers in the current law, meaning individuals who process data on behalf of the controller).

Thus, citizens must be informed about who will own and process information about them and the purpose of data collection and processing. In case of changes in the purpose or address of the controller or processor, citizens will need to be notified.

Moreover, for instance, in the current law, citizens’ rights are merely listed (the right to access their data, the right to submit a reasoned request to the owner of personal data objecting to processing, the right to change or destroy their data, the right to withdraw consent for the processing of personal data, and the right to know the mechanism of automatic processing of personal data).

In contrast, the draft bill elaborates on each of these rights of citizens and the controller’s obligations to comply with these rights. For example, the controller must provide detailed information about themselves, the data processor, contact details of the person responsible for personal data protection, grounds for data processing, etc.

Harmonization of terminology with EU norms. The list of definitions is aligned with European standards. Thus, the draft introduces definitions of biometric data (such as fingerprints and digitized facial features) and genetic data (including health-related information).

Targeted approach. Currently, the law defines the specifics of processing certain types of data (sensitive data) — data concerning a person’s religious, political, and other self-identifying beliefs, biological and genetic data, information about health, etc.

These can be processed under certain conditions: upon the citizen’s consent, to protect their health, to ensure military registration of conscripts, military service members, and reservists, etc.

The draft bill delineates approaches to data processing depending on the purpose of such processing. Specifically, sensitive data can be processed for purposes of significant public interest and for the disclosure or punishment of crimes.

However, such data cannot be processed for military registration or storing information in state registers. Handling such information will be the responsibility of officials accountable for disclosing confidential information.

The draft expands the rights of data subjects, including the right to erasure (deletion, destruction), the right to object (modify), the right to restrict processing, the right to data portability (request for data collected on the Internet), etc. The conditions for obtaining consent for the processing of personal data are significantly detailed.

Posthumous use of personal data. Separately, the draft law defines the procedure for processing data after the data subject’s death, which is not provided for in the current law. Thus, the data of a deceased person may be used or processed with the consent of close relatives of that person: children, spouse (widower/widow), and, if they are absent – parents, brothers, and sisters.

Responsibility for data protection and clear procedures for data breach notification. The project obliges controllers and processors to implement technical and organizational measures to ensure privacy and data protection.

They must assess the risks of data loss or destruction and ensure their reliable protection, and in case of threats, notify both citizens and the supervisory authority.

The controller must notify the supervisory authority within 72 hours after becoming aware of a personal data breach, except in cases where the breach is unlikely to result in a risk to the rights and freedoms of individuals.

Additionally, the controller will be obligated to notify the data subject of the data breach if there is a high risk of infringement on the rights and freedoms of individuals.

The controller is not obliged to notify the data subject if (1) the controller has implemented appropriate and sufficient data protection measures before the data breach or (2) the controller has taken measures to prevent risks of a high degree to the rights and freedoms of the data subject, or if (3) the notification would impose an excessive burden on the controller. However, the draft does not detail what a burden means and how it should be measured.

Transfer of data to other countries. The current law only states that data may be transferred, provided that the receiving state ensures proper protection of such data. The government determines the list of countries capable of providing the required level of protection through its Resolution (the draft proposes that the newly created Commission do this). This includes 58 countries (the so-called “white list“) including EU countries, the US, Canada, and Turkey. In exceptional circumstances, data may be transferred to countries outside the list with the consent of the data subject (i.e., the person to whom the data pertains) to ensure their vital interests, to safeguard public interests, or if the data controller guarantees non-interference in the personal and family life of the data subject (without specifying what such guarantees entail).

The new draft law provides clarification and expansion of the list of entities to whom personal data may be transferred abroad. International organizations and transnational corporations have been added to the list. Additionally, for countries that did not make it to the “white list,” the list of guarantees they must provide to obtain data has been specified. Data transfer to such countries must be allowed by the supervisory authority’s decision — the National Commission for the Protection of Personal Data and Access to Public Information.

Processing of personal data for law enforcement purposes. The draft requires law enforcement agencies to separate and process information about different categories of subjects (suspects, convicts, victims, and other participants in criminal proceedings) in different databases.

Penalty sanctions. The draft law proposes to establish different types and amounts of fines for violations of legislation in the field of personal data protection — from UAH 10,000 UAH to UAH 150 million, or up to 8% of the total annual turnover of a legal entity. Currently, the maximum fine is UAH 34,000.

More about the differences between the draft law and the current law can be found in the tables in the appendix.

Conclusions

Adopting and implementing these proposed bills will adapt the current legislation to European standards and strengthen the protection of citizens’ personal data. However, Bill 8153 risks granting excessive discretion to government authorities and their employees. This level of discretion is average for EU legislation, where laws only provide a general framework or principles for officials’ actions. Traditionally, Ukrainian laws tend to provide clear definitions of terms, criteria, etc. Therefore, in practice, issues may arise with defining high/low risks, “excessive burden,” “necessary and sufficient measures,” and so on.

Establishing an independent collegial body to protect personal data instead of a government service or human rights ombudsman (project 6177) is also a positive development. However, like other independent regulators such as the Antimonopoly Committee of Ukraine or the National Energy and Utilities Regulatory Commission (NEURC), there is a risk of “capture” — when one political group effectively controls this independent body. If this occurs, the Commission’s significant powers (such as imposing fines) could be used to pressure businesses.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations