One of the famous narratives of Russian propaganda: sanctions are not working and they are not efficient. Indeed, despite 25 000+ different sanctions (mostly concentrated on Russian economy) Russian Federation is not only still alive but is able to continue the biggest war in the world since WWII. At the same time, Russia starts any negotiations with demands to lift the sanction pressure. This is a little bit suspicious: why is it so important to ease “non-working and inefficient” sanctions?

One of the explanations for this phenomenon in the economic sphere is simple: fabrication or concealing of statistics by Russian authorities, such as Rosstat (Russian statistical agency). It is a form of propaganda used to create the image of “strong and invincible Russia” (Plastun et al., 2024).

However, there is one area of Russian activity where we have unbiased data: international science. The results of sanctions against Russian science can be evaluated more or less precisely. We have done this in Kozmenko et al (2025) and summarize our research in this article.

International sanctions against Russian academia involve a range of measures, including bans on the supply of equipment and technology, termination of cooperation in projects and grants, suspension or reduction of funding, restrictions on academic mobility, limited access to international databases, and constraints on the ability to publish research findings, among others (Plastun, 2025).

In June 2022, the US announced the closure of federally funded research partnerships with Russia (Ambrose, 2022). The G7 science ministers pledged to restrict government-supported collaborations involving Russian entities. The European Commission froze all agreements with Russian partners and suspended payments under programs like Horizon 2020 and Horizon Europe, where Russia previously participated in 138 projects and received €14 million. Germany immediately halted all joint educational and research activities, while the UK withdrew funding from projects with ties to Russian institutions and banned new collaborations. The Netherlands, Denmark, Latvia, Lithuania, and Finland all froze academic ties, suspended exchanges, and prohibited new partnerships with Russia and Belarus (Upton, 2022a, 2022b). Similarly, Norway cancelled cooperative calls for research proposals, Poland ceased collaboration across academic sectors, and Canada urged scientists to avoid links with Russian industry.

In response to Russia’s continued military aggression, several international scientific collaborations have been suspended at the project level. CERN officially terminated its cooperation agreement with the Russian Federation starting from November 2024. The European Space Agency (ESA) also ended its joint work with Roscosmos on ExoMars and the lunar projects Luna-25, Luna26, and Luna-27. The EU-backed CREMLINplus initiative terminated its partnership with Russian participants. Massachusetts Institute of Technology suspended the project on Moscow’s western outskirts development. Closure of bilateral projects with Russia is also detected in Australia and Germany (German Research Foundation Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and the German-built eROSITA telescope).

The corporate sector has also responded, with multinational corporations adjusting their social responsibility strategies and withdrawing R&D operations from Russia, as highlighted by Kharchenko et al. (2024). Major global tech firms imposed corporate sanctions in science. Mostly in 2022, research centers and facilities were closed all over Russia by Dell Technologies (RFE/RL, 2022), Nvidia and Siemens, IBM, and SAP. Intel sold its facilities in Russia in 2023. Nokia closed its laboratories at Skolkovo and St. Petersburg and officially exited the Russian market.

Supply chain level disruptions critically affected equipment, reagents, and materials procurement procedures for Russian institutions. Before the full-scale war at the beginning of 2022, up to 80% of equipment tenders were won by foreign companies, and dependence of the “life sciences” on Western reagents was about 90%.

A substantial share of research equipment used in Russia is sourced from European and American laboratories. According to COMTRADE data, in 2020, approximately 13.8% of Russia’s imported scientific equipment originated from Germany, while 6.1% was supplied by the United States. Following the invasion, the European Union imposed restrictions on the export of various categories of technical equipment to Russia. In response, major companies such as Zeiss, Nikon, and Thermo Fisher Scientific either halted or suspended their supplies to Russia.

The easiest way to assess the impact of sanctions on Russian academic publication activity is to explore bibliographic databases. The largest and most famous databases to date are Scopus and Web of Science (WoS). Today, Scopus is bigger than WoS. It has 1.8 billion cited references dating back to 1970, 84 million records, 17.6 million author profiles, more than 25,000 active titles, and 7,000 publishers (Elsevier, 2023). Scopus journals’ coverage is higher than in WoS (42,000 vs. 34,200) and broader (including life sciences, humanities, etc.), which is vital for comparison. The content of these databases overlaps significantly.

The period of analysis is 2013–2024 (2013 was the last year before the occupation of Crimea and the creation of the so-called Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR) and the Luhansk People’s Republic (LPR) controlled by Russia. In the first period of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine (2014-2022) there were no official or systematic efforts to sanction Russian science, and after the full-scale invasion in 2022-2024, sanctions were introduced. The data was collected on May 1, 2025.

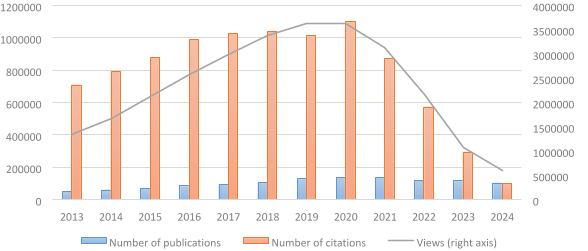

Since the start of the full-scale war the publication activity of scientists affiliated with Russia significantly declined compared to 2021-2022. Figure 1 provides the dynamics of key metrics (number of publications affiliated with the Russian Federation, number of citations, and number of views) for 2013–2024. Note that during the first stage of the war, in 2014-2021, the number of publications, their citations, and views steadily increased. They peaked in 2021, when there were 137.5 thousand publications; the most citations and views were observed in 2020 (1,102,231 citations and 3,619,050 views).

The sad fact is that this growth of Russian publication activity was supported by Ukrainian academicians as well. Even nowadays (summer, 2025) we have revealed 80+ Ukrainian academicians still mentioned as editorial board members of Russian journals.

Figure 1. Key indicators of publication activity affiliated with the Russian Federation for 2013–2024

Source: Built-in Scopus instruments and Scival. Note: number of citations shows how many times papers published in a given year were cited (i.e. how many citations they generated)

The number of publications affiliated with the Russian Federation in 2022 was 14% lower than in 2021, and the number of publications in 2024 was 26% lower than in 2021. For citations, the decline was much larger: in 2022, there were 34% less citations than in 2021, and in 2024 their number was 89% lower than in 2021. The number of article views in 2024 fell by 81% compared to 2021.

Note that at least several months pass between the date of submission of the manuscript and the date of its publication, hence, some papers published after sanctions were introduced were submitted for publication well before that. The citation count in SciVal reflects the total number of citations of papers published in a given year, regardless of when those citations occurred.

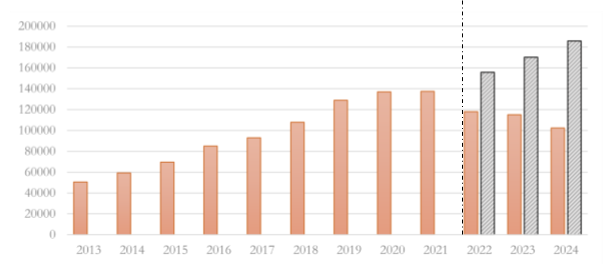

Based on the average growth rate during 2013–2021 (13.3%), the number of publications in 2022 should have been 155,814 instead of the actual 118,054, and in 2024 185,784 instead of actual 102,434 (Figure 2). This means up to 45% (!) of publications were not published in 2024 because of sanctions.

Figure 2. Real (orange) and projected (grey) number of publications affiliated with the Russian Federation for 2013–2024

Source: Built-in Scopus instruments, Scival, and authors’ calculations.

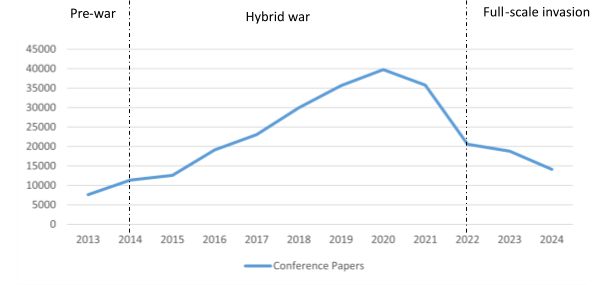

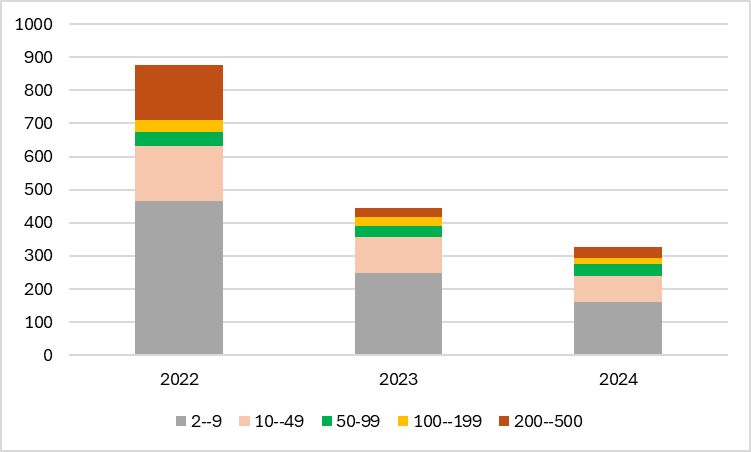

One of the most prominent examples (and the most expected because of rogue-state status) is the proportion of academic conference papers with authors affiliated with Russian universities or research institutions, which fell by 57% in 2022, with a further drop in 2024 (see Figure 3). For example, the Journal of Physics Conference Series (by the United Kingdom) accepted 5,912 papers from Russian scientists in 2021, 1023 in 2022 (Matthews, 2023), and only 213 in 2024 (83% less). The same trend is observed for the Institute of Physics (IoP) Conference Series Earth and Environmental Science (also by the United Kingdom): in 2021, there were 5712 papers, and in 2024, only 68.

This decline occurred via different channels: either directly (for example, the Institute of Physics explicitly announced that they would not commission papers from Russian or Belarusian institutions) or indirectly (e.g. Western institutions cannot get payment fees from Russia or Belarus, Russian scholars cannot get visas or are afraid to go).

Figure 3. Conference papers outputs with Russia-affiliated authors in 2000–2024

Source: Built-in Scopus instruments

Based on the subject area analysis, the biggest losses (more than 40% decrease in number of publications) in academic activity in 2022 were generated in energy, earth and planetary sciences, and environmental science. Physics and astronomy have lost 19.59% in Scholarly Output (i.e. the number of publications indexed in Scopus) after the invasion, economics, econometrics, and finance – 17.29%. In 2024, almost all subject areas had a decline in publication activity compared to 2021, most notably environmental science (–50.59%), earth and planetary sciences (–47.13%), decision sciences (–44.84%). On the other hand, areas such as dentistry and agricultural and biological sciences have seen a growth in their Scholarly Output (+21.48% and +2.55%, respectively).

A similar analysis of the case of institutions showed that in the top 10 Russian academic institutions, seven have lost from 20% to 40% of scholarly output and from one-sixth to one-fifth of authors (Table 1). An interesting observation is that in the top 10 institutions in the government sector (i.e. those affiliated with the Russian Academy of Sciences or some ministries), 40% demonstrated a decline in scholarly output, but in the academic sector, 80% have seen their publications decline.

Table 1. Institutions with the biggest losses in academic activity between 2021 and 2024

| Institution | Scholarly Output (% change) | Number of authors who published (% change) |

| St. Petersburg National Research University of Information Technologies, Mechanics and Optics (ITMO) | –41 | –26.5 |

| Novosibirsk State University | –34.5 | –22.4 |

| Moscow Engineering Physics Institute | –30.8 | –25.6 |

| Tomsk State University | –24.4 | –13.8 |

| Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology (on OFAC and SDN sanctions list) | –20.8 | –14.3 |

| Ural Federal University | –20.5 | –14.8 |

| Peter the Great St. Petersburg Polytechnic University | –19 | –20.5 |

| Kazan Volga Region Federal University | –17.7 | –14.5 |

| St. Petersburg State University | –13.2 | –7 |

| Lomonosov Moscow State University | –6.6 | –4.2 |

Source: Scival and authors’ calculations. Note that these institutions are mostly not sanctioned individually, so this is the effect of general sanctions

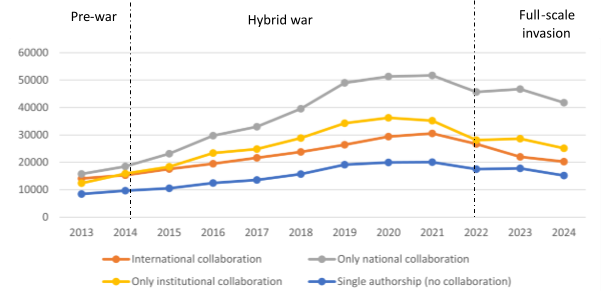

A downward trend is also observed in different forms of collaboration with Russian scientists (Figure 4). In 2022, both international and national collaborations, as well as individual authorship, fell by 12%. Institutional collaboration decreased by 20%. In 2024 the decline continues, in particular, the international collaboration is by 34% lower than in 2021.

Figure 4. Changes in collaboration metrics by the Russian Federation scientists for 2013–2024

Source: Built-in Scopus instruments, Scival, and authors’ calculations.

From the point of view of collaborating countries/regions, the most important ones for Russian academia nowadays are Europe, Asia Pacific, and North America. In the geographical dimension, Russian academia shows patterns similar to its economic and political spheres — a shift from Western countries to China, India, and Turkey.

In the top 20 countries by co-authored publications after the full-scale invasion, 19 (95%) decreased activity by 2024, and only India slightly increased it. The most significant drop in the top 20 is observed in Ukraine (70% – see Figure 5), Poland (54%), and Germany (47%).

Figure 5. Papers where Ukrainians and Russians are co-authors by year of publication

Source: Built-in Scopus instruments, Scival, authors’ calculations. Note that some papers have a very large number of co-authors (usually these are produced under some large-scale international research projects), so Ukrainian scientists have no leverage over who else participates or may not even know all the project participants

This decline may be attributed not only to international sanctions but also to a number of additional factors. They include reduced research funding, brain drain due to the emigration of highly qualified scientists from Russia, limited access to international collaboration and data infrastructure, reputational isolation within the global academic community, and increasing political control over academic institutions and research agendas within Russia.

Findings reveal that sanctions against Russian science are quite efficient and provide evidence in favor of further efforts in this direction. At the onset of Russia’s full-scale invasion, Dmytro Chumachenko, in an Open Letter from Scientists of Ukraine, provided a comprehensive list of such efforts. These included cutting Russian access to research databases and publishers, banning their participation in international grants and exchange programs, boycotting scientific events in Russia, and excluding Russian scholars from journal editorial roles.

Despite the efficiency, the sanctions imposed on Russian science cannot be described as global, systematic, or consistent. In most cases, they represent only isolated elements of what could be a broader and more effective sanctions strategy. Additional measures could include initiating a new wave of academic debate on sanctions against Russian science, developing coordinated sanctions policies by the EU, US, and other partners, and reviewing collaborations with Russian academic institutions and journals to prevent support for the war or violations of academic integrity in scientific papers. Moreover, excluding from indexing any papers that mislabel Ukrainian territories as part of Russia, banning the responsible authors and journals. Finally, one should exclude Russian academic institutions involved in propaganda or war support from the international academic organizations.

These measures could increase the pressure on the Russian Federation in general and might speed up the end of the war.

References

- Kozmenko, S., Vorontsova, A., Ostapenko, L., Plastun A., & Plastun, V. (2025). Sanctions on Russian academia: Are they efficient?. Journal of International Studies, 18(2), 255-269. doi:10.14254/2071-8330.2025/18-2/14

- Plastun, O. (2025, March 13). Free fall of Russian science. Mirror of the Week.

- Plastun, A., Vorontsova, A., Slyvka, Y., Yatsenko, O., Huliaieva, L., Sukhonos, V., & Bilokin, R. (2024). Illusion of stability: An empirical analysis of inflation data manipulation by Russia after 2022. Public and Municipal Finance, 13(2), 68-82.

Photo: depositphotos.com/ua

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations