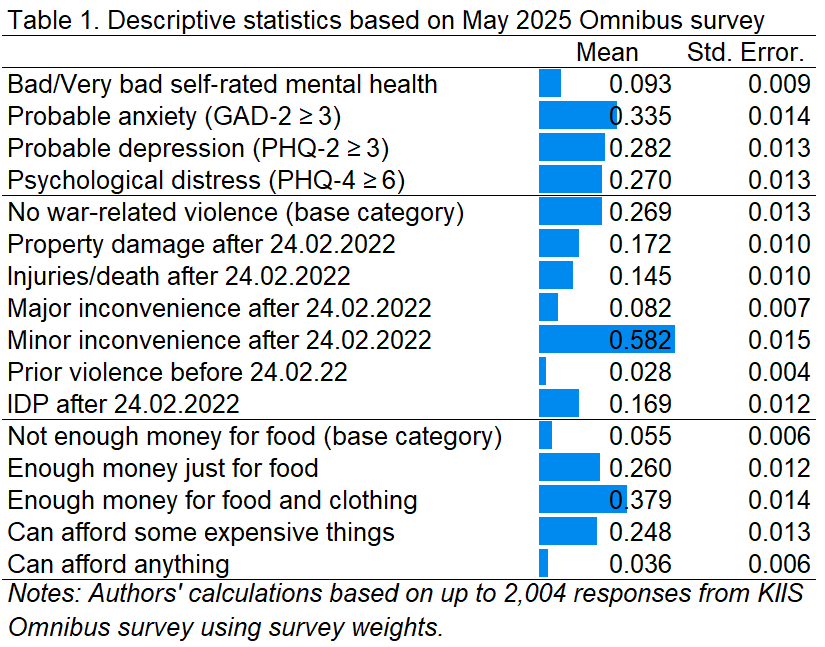

A nationally representative survey of 2,000 Ukrainians from May 2025 reveals substantial war-related mental health impacts: 33.5% of respondents suffer from probable anxiety and 28.2% report probable depression. These prevalence rates are nearly six times higher than pre‑war estimates!

Preliminary analysis indicates a compelling result: war-related violence is so widespread that it is not associated with worsening mental health. Economic well-being, on the other hand, is found to be a robust predictor of mental health resilience, suggesting that material security may serve as a critical protective factor against psychological distress in conflict-affected populations.

War and mental health

What affects people’s mental health during war? The determinants of mental health outcomes in conflict-affected populations remain incompletely understood, particularly regarding the relative contributions of direct violence exposure versus socioeconomic factors. Data from a nationally representative survey (N = 2,000) conducted in Ukraine provide empirical evidence addressing this question. Analysis reveals a paradoxical finding: despite widespread exposure to war-related violence, this variable demonstrates no significant association with mental health indicators across the sample. This null effect may reflect a ceiling effect whereby near-universal trauma exposure eliminates variance necessary for detecting associations. Instead, economic security is the strongest and most consistent predictor of psychological resilience.

To study the effect of various factors on mental health of Ukrainians we commissioned questions to be added to the May 2025 Omnibus survey by Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (KIIS) which includes a detailed portrait of respondents’ socio-economic and demographic characteristics, including gender, age, displacement status, region, education, occupation, and perceived material well-being. Survey weights were applied to account for deviations from the population structure before the full-scale aggression (State Statistics Service of Ukraine, January 1, 2021), allowing for national representativeness and meaningful inferences about mental health trends during the ongoing conflict.

We focus on four main mental health outcomes: self-rated mental health, probable anxiety, probable depression, and psychological distress. The mental health outcomes (except for self-rated mental health) are assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4), a validated ultra-brief screening tool for psychological distress (Kroenke et al., 2009). The PHQ-4 consists of four items: two measuring anxiety symptoms (Generalized Anxiety Disorder-2 or GAD-2: “feeling nervous, anxious or on edge” and “not being able to stop or control worrying”) and two measuring depressive symptoms (PHQ-2: “little interest or pleasure in doing things” and “feeling down, depressed, or hopeless”).

Respondents rate how often they have been bothered by each symptom over the past two weeks using a four-point scale: Not at all (0), Several days (1), More than half the days (2), Nearly every day (3). Thus, subscale scores for anxiety and depression range from 0 to 6, and the total PHQ-4 score ranges from 0 to 12. Following the cutoffs established in the literature, we define probable anxiety as a GAD-2 score ≥ 3, probable depression as a PHQ-2 score ≥ 3, and moderate-to-severe distress as a total PHQ-4 score ≥ 6 (Kroenke et al., 2009). In addition, we include a binary indicator for self-rated mental health, coded as “bad/very bad” versus other responses, based on the respondent’s direct evaluation of their mental well-being.

Mental health during the war

In 2021, according to Global Burden of Disease (GBD) estimates, the prevalence of anxiety disorders was 4.50% in Ukraine and 4.60% in Poland, indicating that Ukraine’s pre‑war levels were broadly comparable to those of its western neighbour (Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 Results). The prevalence of major depressive disorder was higher in Ukraine – 5.02% versus 1.98% in Poland. Previous research has already documented high levels of psychological stress symptoms, including depression and anxiety, among internally displaced persons (IDPs) and veterans (Singh et al 2021) after the start of Russian aggression in 2014, albeit on a smaller scale in Crimea and Donbas. The situation has likely worsened after the full-scale invasion of 2022 which affected a much broader population. Indeed, Table 1 reports much higher estimates of probable depression and anxiety in war-torn Ukraine based on the May 2025 Omnibus study.

Our estimates derived from the PHQ‑4 screening tool cannot be directly compared with the Global Burden of Disease (GBD 2023). PHQ‑4 uses two‑item subscales (PHQ‑2, GAD‑2) to capture core depressive and anxiety symptoms over the preceding two weeks, identifying probable cases rather than applying full diagnostic criteria. In contrast, GBD estimates are based on large epidemiological surveys using structured diagnostic interviews and typically refer to 12‑month prevalence.

Nevertheless, the gap between the estimated wartime prevalence of probable anxiety 33.5% and depression 28.2% is large enough to indicate a substantial worsening of the mental health burden attributable to the conflict. Although nearly six times higher than the GBD estimates for Ukraine in 2021, these figures are strikingly consistent with a systematic review covering 1945–2022, which reported aggregate prevalence rates of 30.7% for anxiety and 28.9% for depression in war- and conflict-affected populations around the world (Lim et al. 2022).

A combined indicator of moderate-to-severe distress based on a total PHQ-4 score greater than or equal to 6 characterizes 27.0% of respondents. Despite such high numbers of anxiety, depression and distress, Ukrainians tend to underestimate this burden with only 9.3% of respondents indicating bad or very bad self-rated mental health.

Table 1 also reports descriptive statistics for key explanatory variables of interest: measures of violence and subjective financial status that are in the focus of the current study. A substantial share of Ukrainians report some form of war‑related violence in May 2025. The most common experience was minor inconvenience, such as temporary service disruptions, reported by 58.2% of respondents. Smaller but still significant shares experienced property damage (17.2%), internal displacement after February 24th, 2024 (16.9%), injuries or death of relatives or friends (14.5%), or major inconvenience (8.2%) such as life-threatening lack of food or medicine. Prior violence associated with Russian aggression in Crimea and Donbas before February 24, 2022 was relatively rare, and reported by only 2.8% of respondents. Overall, only about one in four respondents (26.9%) fell into the base “no war‑related violence” category, underscoring the high prevalence of conflict‑related disruption in everyday life.

Economic hardship is also widespread, but its severity varies considerably. Only 5.5% of respondents reported not having enough money for food, while an additional 26.0% said they had just enough resources for food. The largest group, 37.9%, could afford food and clothing but not expensive items (such as a fridge), suggesting moderate but still constrained resources. About a quarter (24.8%) said they could afford some expensive things, and a small minority of just 3.6% reported being able to afford anything they wanted. These figures highlight a spectrum of subjective economic well‑being, with a large share of the population clustered in the middle range but still far from financial comfort.

What affects the mental health of Ukrainians?

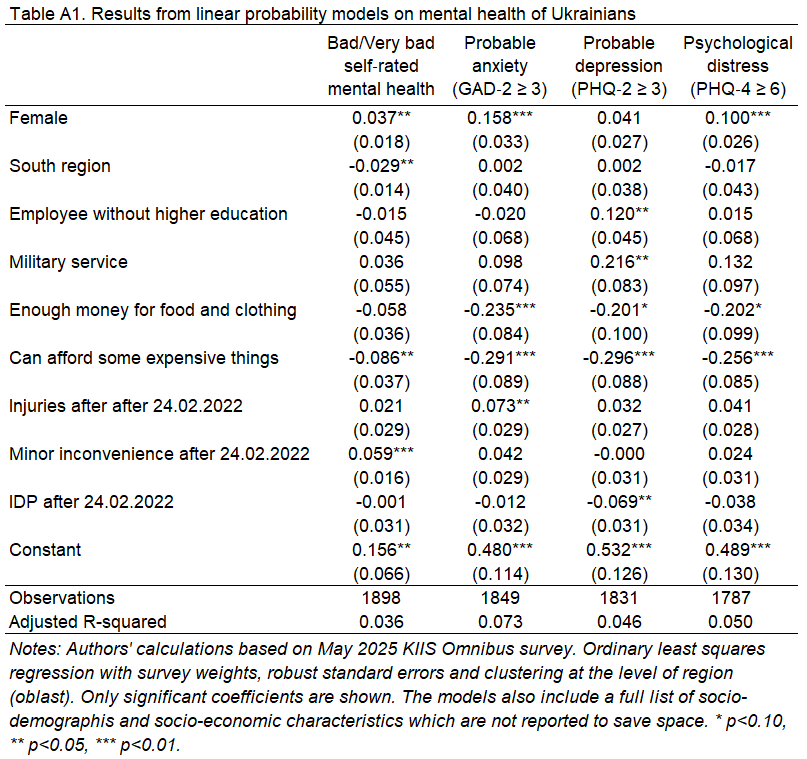

We employ linear probability models to assess the effects of the war (measured by different forms of violence) as well as other factors on mental health. In particular, we estimate models for 4 binary variables identified above: whether respondents report (i) bad or very bad self-rated mental health, (ii) probable anxiety, (iii) probable depression, and (iii) moderate-to-severe distress. The base category includes living in settlements with less than 20 thousand people, having high school education or less, being a manual worker and not having enough money for food. Linear probability models are estimated using ordinary least squares with survey weights, robust standard errors and clustering at the level of region (oblast).

Preliminary analysis in Table A1 in Appendix reveals a striking and consistent pattern across all four outcomes: material well‑being emerges as the strongest predictor of better mental health. Compared to respondents who reported not having enough money even for food (base category for subjective financial status), those who said they could afford some expensive items were 29.1 percentage points (significant at 1%, unless reported otherwise) less likely to report anxiety, 29.6 percentage points less likely to report depression, and 25.6 percentage points less likely to meet the threshold for moderate-to-severe psychological distress.

Those respondents who could afford only food and clothing were 29.1 percentage points less likely to have probable anxiety than those in the poorest group (base category of not having enough money for food). They are also less likely to have depression and distress, but the effects are only marginally significant at 10%.

These findings are supported by recent international research. A 2024 scoping review of youth displaced by conflict found that poverty was mentioned among three most frequent factors unfavorable for mental health (Otorkpa et al 2024).

Another surprising result is that war-related violence is not associated with mental health problems in most cases except for two. Injuries or death of relatives or loved ones are associated with 7.3% points elevated risks for anxiety (significant at 5% only). Minor inconveniences such as power outages or the unavailability of necessary goods (the most common form of war violence which affected 58.2% of respondents) are associated with 5.9% points higher probability of bad or very bad self-rated health.

Other violence-related indicators, including property damage, exposure to earlier violence before 2022, and major inconvenience (such as life-threatening lack of food or medication), were not significantly associated with any of the four mental health outcomes.

The survey also includes a wide range of socio-demographic characteristics (age, gender, city size, macroregion, education and occupation) which have been described in our earlier study based on KIIS Omnibus survey. While they help to avoid the omitted variable bias, none of them are significant at 1% except for female gender.

Gender differences in mental health outcomes were substantial. Women were 15.8 percentage points more likely than men to meet the threshold for anxiety, and 10.0 percentage points more likely to report moderate or severe distress. These gender gaps are consistent with global evidence on women’s greater vulnerability to stress and internalizing disorders during times of crisis. For instance, the same scoping review found that female sex was a robust predictor of poor mental health across multiple conflict zones even more frequent than poverty (Otorkpa et al 2024). This reinforces the urgency of making mental health support more accessible to women, especially in lower-income households.

A highly policy-relevant finding is the lack of strong geographic variation in mental health outcomes. Respondents from the West, South, and East of Ukraine reported similar levels of anxiety, depression, and distress compared to the base category of the Center. In fact, the only regional difference was a slightly lower likelihood of reporting bad or very bad mental health among respondents in the South — a difference of just 2.9 percentage points (significant at 5%). City size also had little to no influence, including no effect of living in regional (oblast) capital. The only two marginally significant effects are a 13.3 percentage point lower reported probability of depression (significant at the 5% level) among respondents from cities with 20–49K inhabitants, and a 9.1 percentage point reduction in probable depression (significant at the 10% level) among those from cities with 50–99K inhabitants, compared to respondents living in villages.

Among other socio-demographic characteristics significant at 5%, we can also mention higher probability of depression for employees without higher education (by 12.0%) and those in military service (by 21.6%).

One might expect that education or job status would protect mental health, but the evidence from Ukraine suggests otherwise. None of the education levels, including higher education, were significantly associated with lower risk of anxiety, depression, or distress. Students, retirees, and those in professional or self-employed roles showed no significant differences either.

Discussion and conclusions

Sabes-Figuera et al. (2012) studied war-affected communities in European countries of Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Kosovo, FYR Macedonia, and Serbia as well as refugees in Germany, Italy and the UK. Their results indicated that psychological consequences of the war were linked to elevated long run healthcare costs, particularly among individuals who remained in conflict-affected areas. Thus, prioritizing the mental health impacts of war is essential not only for humanitarian and public health reasons, but also due to the long-term economic implications.

Our results are consistent with previous literature and suggest that the day-to-day experience of economic insecurity (worrying about having enough to eat or buy essential goods) is associated with a bigger negative effect on mental health than war-related violence. This is not because violence doesn’t matter but because it is too widespread – only 26.9% of respondents do not report any war-related violence while 52.8% report more than one form of violence. From a policy perspective, this finding implies that targeted (and not populist) financial assistance may be as important for mental resilience as psychological interventions.

References

- Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 Results. Seattle, United States: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), 2023. Available from: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R.L., Williams, J.B. and Löwe, B., 2009. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ–4. Psychosomatics, 50(6), pp.613-621.

- Lim, I.C.Z., Tam, W.W., Chudzicka-Czupała, A., McIntyre, R.S., Teopiz, K.M., Ho, R.C. and Ho, C.S., 2022. Prevalence of depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress in war-and conflict-afflicted areas: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in psychiatry, 13, p.978703.

- Otorkpa, C., Otorkpa, O.J., Olaniyan, O.E. and Adebola, O.A., 2024. Mental health issues of children and young people displaced by conflict: A scoping review. PLOS Mental Health, 1(6), p.e0000076.

- Sabes-Figuera R, McCrone P, Bogic M, et al. Long-term impact of war on healthcare costs: an eight-country study. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e29603.

- Singh, N.S., Bogdanov, S., Doty, B., Haroz, E., Girnyk, A., Chernobrovkina, V., Murray, L.K., Bass, J.K. and Bolton, P.A., 2021. Experiences of mental health and functioning among conflict-affected populations: A qualitative study with military veterans and displaced persons in Ukraine. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 91(4), p.499.

This research was financed by The Medical Faculty at the University of Oslo for the implementation of the project: “The Repercussions of War Violence in Ukraine: Consequences for Mental Health, Substance Abuse and Utilization of Primary Health Care”. The funder didn’t have involvement in the research design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, or in the writing of the report. All views are of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the funder.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations