Lately, there has been a growing stream of reports suggesting that Europe is preparing for a Russian attack—or at least moving toward accepting that such a scenario may occur. Even Aleksandar Vučić, the president of Serbia and arguably Russia’s closest “brother” in Europe, recently stated that Europe is preparing for a possible war with Russia, as this prospect “is becoming increasingly evident.”

It is reasonable to assume that Europe is not only growing increasingly concerned but is also taking concrete steps in response. For example, it has been reducing its engagement with Russia overall—and with Russia’s scientific community in particular.

Since no modern military technology can exist without a scientific foundation, one might expect that Europe had ended all scientific cooperation with a country that may well attack it in the relatively near future. But is that actually the case? Let us look at the data—but first, let us recall the European Union’s official position.

At the macro level, Europe has been the principal driver of sanctions pressure on Russia. From 2022 to the present, the European Union has adopted nineteen sanctions packages. These packages do not include an explicit ban on scientific cooperation, but they do contain a range of restrictions—for example, on supplying equipment (including research equipment), technologies, materials, and reagents to Russia. In addition, extensive restrictions on payments and the movement of funds complicate scientific collaboration, sometimes making it impossible.

At the micro level, most European research institutions have halted all institutional cooperation with Russian research organizations. Many European universities have banned cooperation with Russian universities, and some have extended these restrictions to collaboration with individual Russian scientists. Moreover, a substantial number of European researchers, citing ethical or reputational concerns, have ended their cooperation with Russia and its scientists on their own.

A detailed overview of the sanctions against Russian science can be found here.

The expected consequences include the termination of cooperation with Russia in projects and grant programs; the suspension or reduction of funding; restrictions on the academic mobility of Russian researchers; limited access to international databases; and constraints on the ability to publish research results.

However, the formal position of Europe and its various institutions does not automatically translate into a consensus among scientists. Some of them insist that they are “above politics,” invoke “academic freedom,” argue that “the free circulation of ideas must not be obstructed,” or state that “I have collaborated with Russians my entire life and will continue to do so” etc. There are also more openly pro-Russian voices in Europe— people who sincerely believe that “things are not so clear-cut” or that “Ukraine is to blame.”

For example, one Italian scientist wrote this:

“As an academic, I don’t intend to discuss Russian universities’ policy on the war. Too many gimmicks and manipulative policies are being employed by Ukrainian authorities, which are being passively reported by EU media. However, I can only imagine that Ukrainian universities have supported their government’s mistreatment of the Russian people in Donbass since 2014.”

Or a similar scholar from Finland:

“Science and scholarship know no borders and no wars. Although a citizen of Finland, I am an associated researcher at the Institute for Linguistic Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg, Russia, and in this capacity I have absolutely no moral problems in cooperating with Russia and Russians. My fields of specialization are such that access to Russia is essential for my work.”

And here is another statement from a Serbian “brother”:

“I work in science. Politics does not interest me. I have many friends in both Russia and Ukraine. Naturally, I do not like this war, in which many Ukrainians and Russians are suffering. I hope it will end quickly. My country was bombed by seventeen different states, including the United States, for no reason. And when the Americans say that they will fight Russia to the last Ukrainian—everything becomes clear! Do not think that the United States and Europe love Ukraine… They do not! If Russian academics support V. V. Putin, that is normal, just as Ukrainians support their own leadership.”

In the table below, we present several rather moderate views that help explain tens of thousands of joint publications produced by European and Russian researchers. We do not provide the names or institutional affiliations of the authors of these quotes. We selected them from hundreds of emails we received in response to messages sent to foreign scholars about their cooperation with Russia. (We will soon publish a detailed study based on the responses we obtained.) Together, these quotes offer insight into the actual motivations of European researchers, with the greatest possible geographic differentiation: they come from researchers from Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Czechia, Finland, France, Hungary, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Poland, Slovenia, Switzerland, and the UK.

Table 1. Selected quotes from responses of European researchers to our inquiry on their cooperation with Russians

| Quote |

| I think many (if not most) of Russian scientists cannot be blamed for the criminal policies of the Russian government. I also think that not all scientific connections with Russia should not be severed, in spite of the brutal Russian aggression on Ukraine. I don’t think all Russian scientists should be ostracized from the international scientific community now, unless they were personally outspoken in favor of the war against Ukraine. In the future, when Ukraine hopefully wins the present war, co-operation with Russian academia will have to be resumed, and all connections with it should not be severed even in so dire times as the present ones. |

| I am also on the editorial board of the Crimean ***, which I have joined when the Crimea was Ukrainian and when the Ukrainian authorities solicited the publishers to engage collaboration of Western researchers. This engagement is a token of friendship with the founder of this review |

| I strongly believe in the autonomy of science, which should serve as a bridge — not a wall — between communities, even in times of conflict. Upholding scientific values such as openness, rigor, and critical dialogue is more crucial now than ever |

| I do not think that boycotting academic journals and universities is the right way to put pressure on Russia. Universities have always been the seat of democracy and the defence of human rights. Other means must be used to end this senseless war. |

| I do not approve of Russian aggression against Ukraine, but I believe that science should be apolitical |

| I am very much regretting the invasion of independent UKRAINE by RUSSIAN troops … and do find it an AGGRESSIVE ACT. Otherwise – I am independent scientist and NOT ENGAGED in any political opinion |

| My Russian colleagues have become close friends in those 35 years, and I do not hold them personally responsible for the criminal invasion of Ukraine, even though they work at a University that has followed the mainstream of Russian politics since then. You and I know that only one person is responsible for this war. |

| My Russian colleagues have become close friends in those 35 years, and I do not hold them personally responsible for the criminal invasion of Ukraine, even though they work at a University that has followed the mainstream of Russian politics since then. You and I know that only one person is responsible for this war. |

| As head of one of the most prestigious Slavic institutes in Europe at the University of Heidelberg, which has an excellent reputation worldwide, my word carries weight in the Russian academic world, even though scientific relations with the West have been shattered for quite a time. As a member of the editorial board, I have rejected several submitted articles that were historically and scientifically extremely questionable and attempted to delegitimize Ukraine in line with state propaganda. I would like to continue to work in this way in the future and thus make my contribution to reforming Russia from within. |

| As it is extremely difficult to work on Slavic Philology, for different reasons, I strive to maintain and develop collaborations with foreign scholars from various countries—including, due to my research interests, a significant number from Russia—regardless of the political climate and as independently from it as possible. I also have strong working relationships with colleagues in other “problematic” contexts, including my own country. While I understand and respect your position, I believe it is essential not to isolate fellow researchers who are operating under pressure or in difficult circumstances. In my view, it is imperative to continue engaging with them along a rigorous and principled scientific path |

| To be clear, my attitude to the Russian aggression and other geopolitical adventures of the Putin regime has been unequivocally negative. I have also supported Ukraine in its war against aggression. However, I do not support the policy of boycotting everything that is Russian and making all Russian people and institutions collectively responsible for decisions taken by Putin and his entourage. This is unfair (given the increasingly authoritarian character of the Russian political regime and mounting repressions against people who openly disagree with the regime) and counterproductive (it helps the Kremlin propaganda). The situation is not black-white, but more nuanced. |

| I strongly oppose Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and have discontinued all formal relations with Russian institutions, which I had held for more than 30 years, after February 2022. I do not see my membership in the editorial board as any kind of of approval of Tomsk State University – although I do not assume that they have a lot of choices other than supporting the war – but as a reflection of my continued personal relationship with the editor, who is not among the winners of the war. |

| I deeply think that, precisely in times of trouble, the humanist way of thinking, not eviling the other for bad reasons but promoting friendship through good research, is to be maintained |

| I have recently welcomed a Russian delegation of dermatologists in Zurich for a day of scientific talks, including an Ukrainian professor, which proves to me the favorable relationship between Russians und Ukrainians in academia. Out of these reasons, I do not see any plausible reason for resigning from the council. |

| I think that resigning would be an empty gesture, which would have no effect on the ongoing Russian terrorist campaign against Ukraine. It might however make it dangerous for my Russian colleagues, none of whom can be blamed for the actions of Putin and his army, to continue to have contact with me. |

As we can see from most of these quotes, even while siding with Ukraine and acknowledging the criminal nature of Russia’s aggression, some European scholars see no problem in continuing cooperation with their Russian counterparts. Their arguments mostly boil down to “science is above politics” and “Putin alone is to blame for the war.”

However, because statements do not always correspond to actual behavior, let us look at quantitative measures of scientific collaboration between Europe and Russia. To do this, we use the Scopus scientometric database and its SciVal analytics service.

Figure 1. Numbers of joint European–Russian publications over time

Source: Scopus/SciVal

According to the data (Figure 1), in 2024, the number of joint publications decreased by 51% compared to 2021, the last year before the full-scale invasion. The decline is quite substantial, as the overall scale of collaboration has been cut in half. In this context, the geographic distribution of Russia’s top coauthors is quite telling. In 2021, eight of the top ten co-authors were from Europe, and one from each South Korea and China. In 2024, all ten of the top coauthors were Chinese. This is yet another piece of evidence supporting the so-called “pivot of Russia to the East.”

Table 2. Top coauthors of Russian researchers

| 2021 | 2024 | ||||

| Author | Country | Number of joint publications | Author | Country | Number of joint publications |

| Shariat, S.F. | Austria | 166 | Li, C. | China | 142 |

| Fabbri, F. | Italy | 150 | Chang, J. | China | 141 |

| Peng, H. | China | 150 | Ji, X. | China | 141 |

| Geralis, T. | Greece | 148 | Chen, M. | China | 138 |

| Boyko, I.R.* | Switzerland/ Russia | 140 | Li, F. | China | 138 |

| Yang, Y. | South Korea | 140 | Zhu, K. | China | 138 |

| Zhemchugov, A.S.* | Switzerland/ Russia | 140 | Dai, H. | China | 136 |

| Çetin, S.A. | Turkey | 140 | Gu, M. | China | 136 |

| Berger, N.B. | France | 139 | Li, H. | China | 136 |

| Dedovich, D.V.* | Switzerland/ Russia | 139 | Zhao, L. | China | 136 |

Source: Scopus/SciVal. *Note. Although some of the European scholars mentioned here and below are clearly of Russian origin, Scopus classifies them as Europeans, and we follow the same classification.

In 2024, according to Scopus, there were 9,253 joint European–Russian publications, indicating that cooperation has continued quite actively. To ensure that we are not dealing solely with large projects in which authors may not even know each another, but rather with direct and deliberate collaboration, we grouped these publications by the number of co-authors. The results are shown in Figure 2.

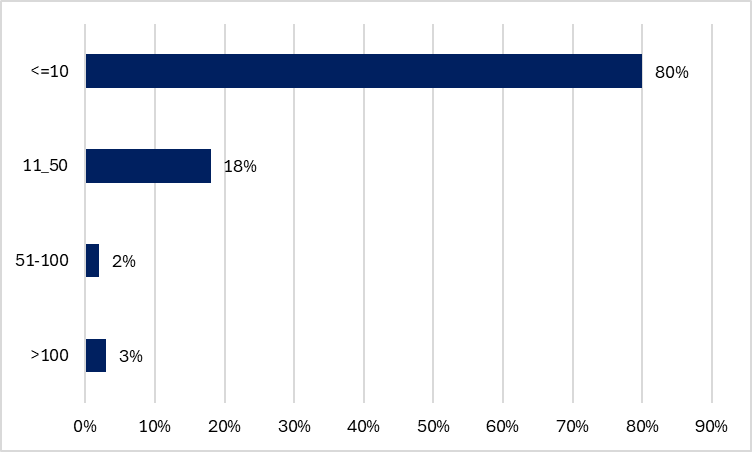

Figure 2. Distribution of articles co-authored with Russians by number of authors

Source: Scopus/SciVal

As we can see, 80% of publications have fewer than ten co-authors. Therefore, this cooperation can be considered a deliberate choice by European researchers.

Let us look at the geographical breakdown of European scholars’ cooperation with Russian researchers and the changes that occurred after the full-scale invasion (Table 3). The largest numbers of scientific collaborators have been—and remain—in Germany, the United Kingdom, France, Italy, Spain, and Poland. At the same time, the steepest declines in the number of joint publications with Russian scientists were recorded in Ukraine (–77%), Lithuania (–66%), Estonia (–65%), and Finland (–64%).

Table 3. Number of joint publications by European and Russian researchers by country

| Country | 2021 | 2024 | Change 2024 vs 2021, % |

| Germany | 5947 | 2547 | -57% |

| United Kingdom | 3824 | 1979 | -48% |

| France | 3445 | 1761 | -49% |

| Italy | 3332 | 1745 | -48% |

| Spain | 2098 | 1159 | -45% |

| Poland | 2006 | 853 | -57% |

| Switzerland | 1584 | 829 | -48% |

| Netherlands | 1604 | 775 | -52% |

| Czechia | 1544 | 722 | -53% |

| Sweden | 1472 | 745 | -49% |

| Ukraine | 1419 | 332 | -77% |

| Finland | 1238 | 442 | -64% |

| Austria | 1330 | 637 | -52% |

| Belgium | 1046 | 590 | -44% |

| Norway | 930 | 437 | -53% |

| Portugal | 856 | 450 | -47% |

| Greece | 843 | 443 | -47% |

| Denmark | 782 | 391 | -50% |

| Hungary | 722 | 372 | -48% |

| Romania | 755 | 374 | -50% |

| Serbia | 685 | 383 | -44% |

| Slovakia | 600 | 246 | -59% |

| Bulgaria | 604 | 303 | -50% |

| Ireland | 533 | 226 | -58% |

| Croatia | 442 | 200 | -55% |

| Estonia | 408 | 142 | -65% |

| Slovenia | 372 | 196 | -47% |

| Latvia | 385 | 172 | -55% |

| Lithuania | 384 | 131 | -66% |

| Cyprus | 237 | 144 | -39% |

| Total | 19023 | 9253 | -51% |

Source: Scopus/SciVal

The main collaborators at the country level have been (and remain) Germany, the United Kingdom, France, Italy, Spain, and Poland. At the same time, all of the analyzed countries have significantly reduced the volume of their joint publication activity with Russian researchers. The largest reductions were recorded in Ukraine (–77%), Lithuania (–66%), Estonia (–65%), and Finland (–64%). An important nuance in Ukraine’s case is that the overwhelming majority of Ukrainian–Russian publications are, in reality, Russian–Russian, because they involve researchers from the occupied territories whom Scopus classifies as Ukrainian.

The top twenty institutions—namely, the direct participants in collaboration in 2024—are presented in Table 4.

Table 3. Top twenty European institutions by number of joint publications with Russian researchers

| # | Organization name | Country | Number of joint publications | Share of top 20 |

| 1 | CNRS (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique) | France | 1024 | 18% |

| 2 | Université Paris Cité | France | 357 | 6% |

| 3 | University of Oxford | United Kingdom | 309 | 6% |

| 4 | University of Turin | Italy | 307 | 5% |

| 5 | Sorbonne Université | France | 275 | 5% |

| 6 | Université Paris-Saclay | France | 275 | 5% |

| 7 | Czech Academy of Sciences | Czechia | 243 | 4% |

| 8 | Uppsala University | Sweden | 243 | 4% |

| 9 | CSIC (Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas) | Spain | 239 | 4% |

| 10 | Charles University | Czechia | 233 | 4% |

| 11 | Commissariat à l’énergie atomique et aux énergies alternatives | France | 232 | 4% |

| 12 | University of Copenhagen | Denmark | 222 | 4% |

| 13 | University of Groningen | Netherlands | 220 | 4% |

| 14 | Harvard University | США | 217 | 4% |

| 15 | University College London | United Kingdom | 210 | 4% |

| 16 | University of Manchester | United Kingdom | 209 | 4% |

| 17 | Goethe University Frankfurt | Germany | 208 | 4% |

| 18 | Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz | Germany | 187 | 3% |

| 19 | University of Münster | Germany | 187 | 3% |

| 20 | University of Rome La Sapienza | Italy | 185 | 3% |

Source: Scopus/SciVal

The distribution of joint publications by type has changed remarkably (Table 4). The share of publications in conference proceedings has declined sharply, a direct consequence of the impact of sanctions on Russian science, as Russian researchers have been attending fewer international conferences.

Table 4. Distribution of joint publications by European and Russian researchers by type

| Publication type | 2015-2024 | 2024 | ||

| Number of publications | Share of total | Number of publications | Share of total | |

| Article | 110564 | 75% | 7281 | 79% |

| Conference Paper | 21103 | 14% | 822 | 9% |

| Review | 7000 | 5% | 533 | 6% |

| Chapter | 3840 | 3% | 262 | 3% |

| Other | 4695 | 3% | 362 | 4% |

Source: Scopus/SciVal

If European scholars had not wanted to see their names alongside Russian ones, one could have expected a substantial increase in the number of retracted publications in 2022. Unfortunately, the number of such publications did not increase. On the contrary, it decreased by several times (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Trends in the number of retracted European–Russian publications

Source: Scopus/SciVal

Table 6 shows which publishers mostly provide a platform for joint publications involving Russian researchers.

Table 6. Journals publishing the largest number of articles co-authored with Russian researchers

| Journal | Publisher | 2021 | 2024 | Change, % |

| Journal of Physics: Conference Series | IOP Publishing | 245 | 27 | -89% |

| Scientific Reports | Nature Portfolio (Springer Nature) | 208 | 79 | -62% |

| Physical Review B | American Physical Society (APS) | 197 | 70 | -64% |

| Physical Review D | American Physical Society (APS) | 195 | 119 | -39% |

| E3S Web of Conferences | EDP Sciences | 175 | 25 | -86% |

| Materials | MDPI | 154 | 21 | -86% |

| Journal of High Energy Physics | Springer Nature (on behalf of the Scuola Internazionale Superiore di Studi Avanzati—SISSA) | 143 | 27 | -81% |

| International Journal of Molecular Sciences | MDPI | 133 | 92 | -31% |

| IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science | IOP Publishing | 123 | 0 | -100% |

| Physical Review Letters | American Physical Society (APS) | 121 | 58 | -52% |

Source: Scopus/SciVal

As we can see, most publishers are based in European countries, with the rest in the United States. In other words, the countries that formally oppose Russia are simultaneously providing platforms for its science thus directly contributing to its development. To understand where the problem lies, let’s look at the top twenty Russian institutions with which European researchers collaborated in 2024 (Table 7).

Table 7. Russian institutions with the largest number of joint publications with European scholars

| Organization | Number of joint publications in 2024 |

| Russian Academy of Sciences | 3,721 |

| Lomonosov Moscow State University | 1,009 |

| Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University | 588 |

| St. Petersburg State University | 566 |

| Higher School of Economics | 536 |

| Joint Institute for Nuclear Research | 509 |

| Ural Federal University | 417 |

| Russian Ministry of Health | 413 |

| RAS – Siberian Branch | 405 |

| Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology | 401 |

| People’s Friendship University of Russia | 337 |

| National Institute for Nuclear Physics | 331 |

| Russian Research Centre Kurchatov Institute | 319 |

| Novosibirsk State University | 273 |

| Kazan Volga Region Federal University | 270 |

| St. Petersburg National Research University of Information Technologies, Mechanics and Optics (ITMO) | 251 |

| Tomsk State University | 241 |

| Russian Academy of Medical Sciences | 217 |

| Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology | 213 |

Source: Scopus/SciVal

All of these organizations support the aggression against Ukraine in one form or another—from providing direct financial and material assistance to the Russian army to aiding the annexation of Ukrainian territories and disseminating propaganda. We illustrate this with the example of Lomonosov Moscow State University.

Case study: Lomonosov Moscow State University (MSU)

First of all, this university signed the so-called “Rectors’ Letter” in support of the aggression against Ukraine. Moreover, MSU’s rector, Viktor Sadovnichii, who also heads the Russian Council of Rectors, initiated the creation of this letter and organized the process of signing it by several hundred (!) Russian universities.

None of this has prevented the international publisher Springer from continuing active cooperation with him. Sadovnichii remains the editor-in-chief of Springer’s journal Differential Equations.

The university has been actively facilitating the annexation of Ukrainian territories, as Sadovnichii stated at the opening of the First Forum of Educational Institutions of Russia and the so-called Donetsk and Luhansk “People’s Republics,” held in Rostov-on-Don on June 3-5. The purpose of the forum was to promote the rapid integration of the universities of the so-called DPR and LPR into Russia’s educational space. After Russia stole Donetsk University from Ukraine, the MSU rector declared that without this university, Donbas would have no future and that everything possible must be done to integrate it into Russia’s educational space. This is precisely the kind of “integration” in which MSU has been engaged.

In early August 2023, representatives of MSU’s Faculty of History visited the stolen Ukrainian universities—Donetsk State University (DonSU), Melitopol State University, and Azov State Pedagogical University. During the visit, they discussed current tasks related to integrating the Zaporizhzhia region into Russia’s sociocultural space, as well as plans for publishing a propagandistic collective monograph on the history of the formation of historical knowledge in Donbas in 2014–2022.

MSU has also been advancing the “integration” of the annexed Ukrainian territories into Russia and supporting the war against Ukraine by granting special admission quotas to “citizens of the DPR and LPR,” as well as to the children of Russian military personnel killed in Ukraine.

As part of its efforts to support Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, the university’s Faculty of Psychology designed a professional development program for psychologists who work with participants and veterans of the war, as well as with their family members. Among other, they provide support to Russian soldiers returning from the war.

MSU staff have been actively brainwashing Ukrainian children living under occupation. As part of the “University Shift—Young Lomonosov” educational program, MSU hosted fifty schoolchildren and five teachers from the so-called Donetsk People’s Republic from September 11 to 20. The schoolchildren met with the rector and visited “Patriot,” a military-patriotic park of culture and recreation operated by the armed forces of the Russian Federation.

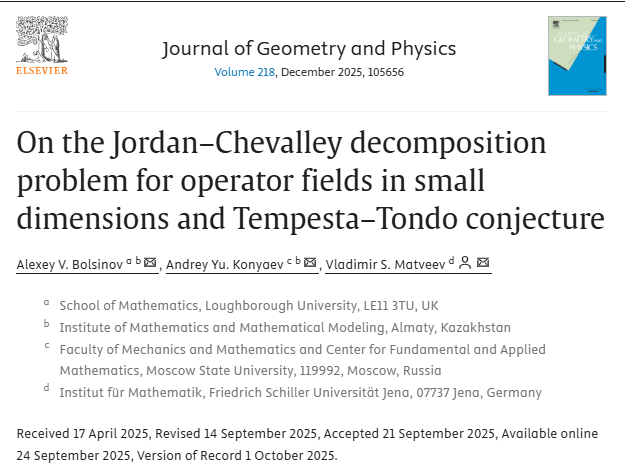

However, when yet another joint article by a European scholar and an MSU representative appears, and the academic community sees something like Figure 4, it receives the signal that collaborating in 2025 with an active supporter of the war against Ukraine is perfectly fine.

Figure 4. Joint article by European and Russian researchers

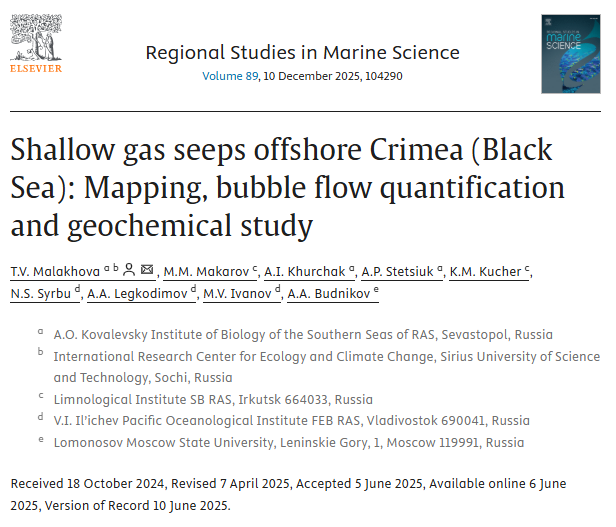

This is not the only signal which MSU sends to the world. As an active supporter of the annexation of Ukrainian territories and a vehicle for propaganda, MSU uses its publications to broadcast messages to the academic universe, such as “Crimea is Russia,” “Donetsk is Russia” etc., as well as the claim that stolen Ukrainian institutions are the property of the Russian state. MSU researchers readily collaborate with these stolen Ukrainian scientific institutions, including the A. O. Kovalevsky Institute of Biology of the Southern Seas, which the Russian Academy of Sciences seized from the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine in 2014. MSU scholars (and not only they) promote the idea that Sevastopol is a Russian city. Unfortunately, colleagues from Switzerland and Belgium join them in this (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Joint article by Russian and European researchers in a journal published by Elsevier (2025)

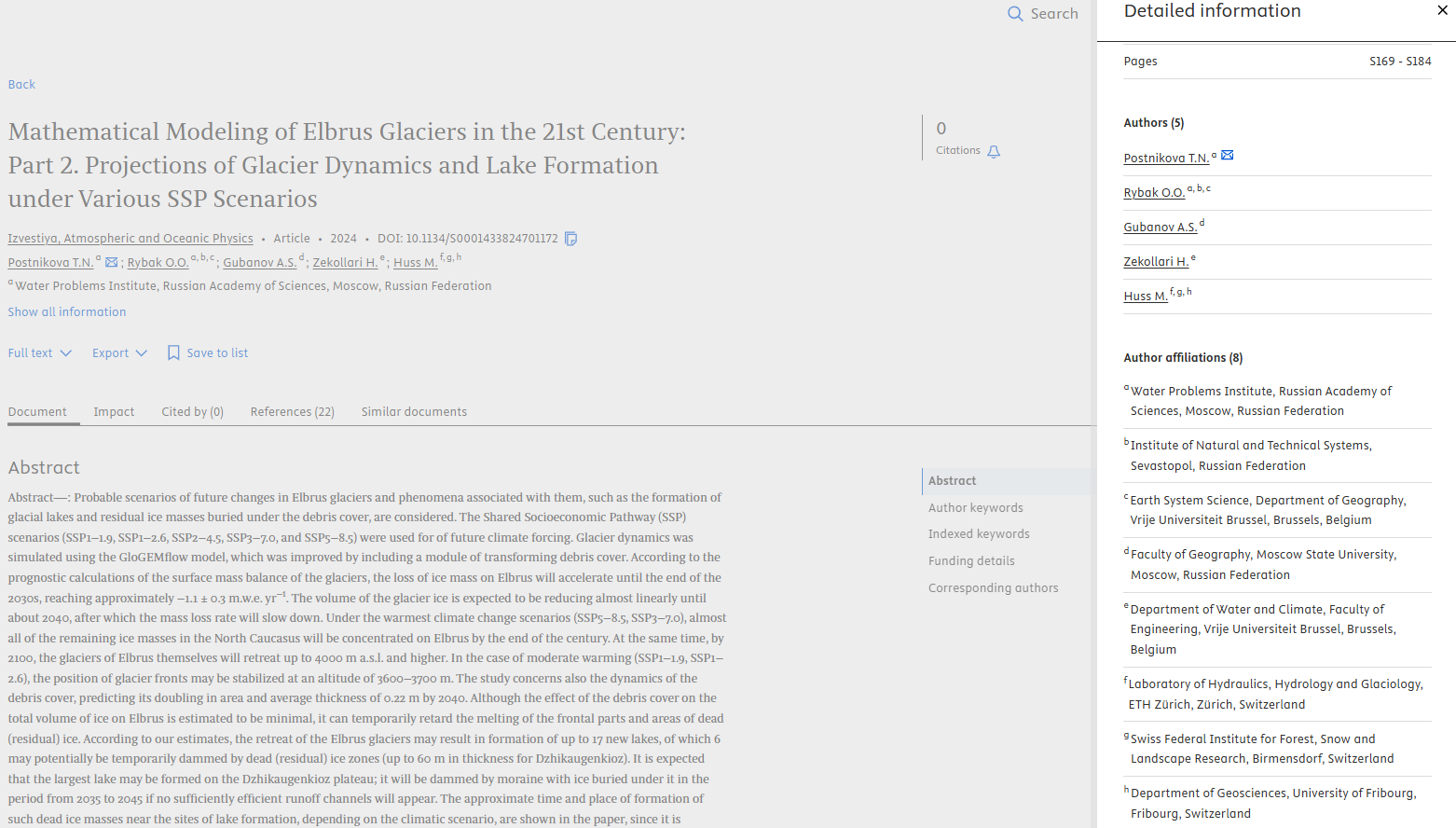

Figure 6. Joint European–Russian article in a journal published by Springer Nature, asserting that Sevastopol is Russia (2025)

And a Slovak scholar, writing in a Slovak (!) journal together with “colleagues” from MSU, insists that Ukraine’s research institute—the Crimean Astrophysical Observatory—belongs to the Russian Academy of Sciences (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Joint Slovak–Russian article claiming that Ukraine’s research institute, the Crimean Astrophysical Observatory, belongs to the Russian Academy of Sciences

All of this contributes to the spread of Russian propaganda narratives, producing exactly the kinds of views within the academic community that we presented in Table 1. So can anything be done about this outrageous situation—and if so, what exactly?

Suggestions

It is evident that the current measures—restrictions on cooperation with the Russian academic community, in some cases an outright ban on collaboration with Russian institutions, sanctions against the Russian economy that also affect payment capabilities and the supply of goods (including reagents and equipment), visa restrictions, and so on—are clearly insufficient, despite their effectiveness (remember an over 50% decline in Europe’s joint publication activity with Russia), because Russian universities and research institutions have largely avoided sanctions. Sanctions are a powerful tool that provides the legal basis for halting cooperation at the institutional level, which then translates into less collaboration at the individual level. Therefore, the list of sanctioned Russian institutions should be expanded.

Given the contentious nature of sanctions against academic institutions (which may be perceived as an attack on academic freedom and the free exchange of ideas), we propose applying sanctions as a punishment for specific actions rather than for the mere fact of belonging to Russia.

That is, if a university has openly and publicly supported the aggression against Ukraine (for example, by signing the Rectors’ Letter mentioned above), this is an entirely legitimate basis for imposing sanctions against it. If a scientific organization or university has been stolen from Ukraine, this should automatically mean inclusion on the sanctions lists. If a research institution is involved in military R&D, it should be on the sanctions lists. And if an academic institution actively assists the military aggression against Ukraine (for example, by collecting money and goods for the army), facilitates the annexation of Ukrainian territories, or engages in propaganda for the war against Ukraine, it should be on the sanctions lists.

Another aspect of addressing the problem is educational outreach—explaining why cooperation with scholars affiliated with Russian institutions contributes to the spread of Russian propaganda and is reputationally toxic. In this context, European authorities could issue formal recommendations and warnings regarding collaboration with Russian researchers, including an explanation of the pitfalls of such cooperation, which we have discussed in this article.

European academic organizations should pay more attention to monitoring the publication activity of their employees, since this can cast a shadow on the entire institution. For example, the terms for concluding or renewing contracts could include the absence of questionable publications—that is, publications co-authored with Russian researchers.

These proposals will not, of course, solve the problem entirely, but they will help reduce Russia’s presence in global science and diminish its propagandistic activity within the academic community.

Photo: depositphotos.com/ua

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations