Populism has been on the rise around the world in recent decades, although we know little about its potential consequences for the citizens of countries governed by populist leaders. In a recent study (Demirci, 2021), I found that the rise in populism in some developing countries, including Ukraine, increases the likelihood that their citizens will pursue a foreign education.

How to detect the effects of populism

To explore the relationship between populism and student mobility, I focused on four countries as early examples of populism: Hungary, Ukraine, Venezuela, and Indonesia. In each of these countries, as a result of closely contested elections around 2010, either a populist leader gained power or an already-ruling populist leader extended his power with new constitutional amendments. An immediate consequence of the election victories of populist leaders was an increase in the authoritarian nature of their government’s policies.

Relating populism and authoritarianism

The classification of leaders/parties is not easy. Guriev and Papaioannou (2021) in their survey article state three common characteristics of populists: 1) distinction between the people and the elites, 2) reliance on identity politics, 3) taking authoritarian angle (i.e., emphasizing law and order against freedoms). Leaders might have more emphasis in some of these dimensions.

For example, Yanukovych’s main point was his authoritarianism. However, he used some identity politics as well, especially to maximize his votes from Eastern Ukraine. In the other analyzed countries, the discourse on distinction between elites and the people was more apparent while they also showed marks of authoritarianism and identity politics. Thus, I decided to use populism as an umbrella term for all of the analyzed countries.

Freedom House has been calculating an index of civil liberties in each country annually since 1972. The index uses a 7-point scale as a measure of freedom of expression and belief, associational and organizational rights, rule of law, personal autonomy and individual rights. For instance, in Ukraine, Viktor Yanukovych won the presidential election in 2010 by a 3-percent margin of the popular vote. In the same year as his election, the civil liberties index deteriorated in Ukraine by 1 point. Similarly, the index of civil liberties deteriorated in 2011 in Hungary after the election victory of Viktor Orbán, in 2009 in Venezuela after the approval of a new constitutional amendment abolishing the limit on the number of terms a president can serve, and in 2013 in Indonesia after Joko Widodo’s election as the governor of Jakarta and during his campaign for the presidential election.

Using the deterioration of civil liberties after a closely contested election as an indicator for the rise in authoritarian populism, I analyzed the effect of the rise in authoritarian populism on the number of international students originating from each country of interest. The key challenge in estimating this effect is estimating what the number of international students would have been if the country of interest had not experienced a rise in authoritarian populism.

To understand the patterns of student mobility in this counterfactual case, I employed the synthetic control method (SCM), which was developed by Abadie and Gardeazabal (2003). In this method, a synthetic control is constructed for the origin country of interest by assigning weights to other countries that have not experienced a rise in authoritarian populism (i.e., other countries where the index of civil liberties has been constant). The method assigns weights to each possible control country optimally by maximizing the similarity in certain characteristics between the origin country of interest and the countries constituting the synthetic control.

In the application of interest, according to the SCM estimates, the synthetic control for Ukraine should be Belarus, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Mongolia, and Slovakia. The assigned weights were, respectively, 0.448, 0.461, 0.052, 0.039 and 0.001. In other words, the weighted averages of the selected characteristics in these countries, including economic output, youth unemployment, trends in youth population, civil liberties, and popularity of certain destination countries among their citizens, were the most similar ones to those in Ukraine. Thus, my estimate of the number of international students that would have originated from Ukraine in the absence of the rise in authoritarianism was calculated as the weighted average of the population of international students originating from these countries.

The impact of populism on student migration

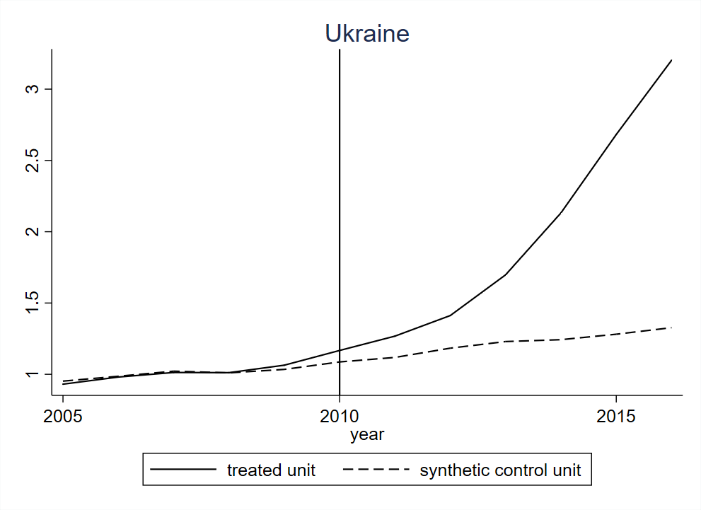

Figure 1 shows the normalized number of international students with respect to the annual average number of students in the pre-populism era in Ukraine and in its synthetic control. The number of outgoing international students was stable both in Ukraine and in its synthetic control until 2010, the year populism took off in Ukraine. After 2010, the number of international students originating from Ukraine increased noticeably while the weighted average for the countries making up the synthetic control remained stable. This divergence shows that the rise of populism in Ukraine increased the outflow of youth as international students from Ukraine. A similar pattern was also observed in the other countries analyzed: Hungary, Venezuela, and Indonesia (as discussed in Demirci, 2021).

Figure 1: Student migration from Ukraine

Notes: Data from the OECD. The solid line shows the normalized population of international students who originated from Ukraine and attended university in an OECD country. The data for a particular year were normalized by dividing the population of international students originating from Ukraine in that year by the annual average population of international students originating from Ukraine in the pre-2010 period. The dashed line shows the normalized population of international students originating from the synthetic control for Ukraine, which consists of Belarus (0.448), Bulgaria (0.461), Czech Republic (0.052), Mongolia (0.039), and Slovakia (0.001). The associated weights are given in parentheses.

Understanding the reasons

Populism may encourage young citizens to study abroad for two main reasons. First, rising populism in a country may lower the quality of higher education in its universities due to difficulties in exercising free speech or in hiring qualified scholars from abroad. Second, the election of populist leaders in a country may restrict personal freedoms and cause a deterioration of its economic outlook. For these reasons, a larger number of young people in countries governed by populist leaders may start pursuing a foreign education with the hope of finding high quality educational options while gaining more personal freedom and better job opportunities abroad.

To understand the validity of these reasons for the observed increase in the number of international students, I compared the patterns of student migration with respect to the characteristics of the destination countries. I present the results of this analysis for Ukraine in Table 1. The results were similar for the other countries of interest, as presented in Demirci (2021).

Table 1: The effect of populism on various outcomes in Ukraine

| Average Annual Effect | Statistically Significant | |

| Output | ||

| Student Migration | ||

| To countries with high-quality universities | 11% | No |

| To countries with lower-quality universities | 219% | Yes |

| To historically more popular countries | 108% | Yes |

| To historically less popular countries | 41% | Yes |

| In the initial three years after the rise of populism | 28% | Yes |

| In the post-three-year period | 154% | Yes |

| Economic Outcomes | ||

| Youth Unemployment Rate (%) | 5 pp | No |

| GDP per capita | -$1,350 | No |

| Scientific Production | ||

| The number of international publications | 17% | No |

Source: Data for student migration from the OECD, data for economic outcomes from the World Bank, and data for academic production from the Scimago.

Notes: Estimates were calculated using SCM. Destination countries considered to have high-quality educational options were those where, annually, at least five institutions on average were in the list of the top-200 universities in the world according to the QS rankings for the 2004-2016 period. These countries were Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Japan, the Netherlands, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The three most popular destination countries among Ukrainian students in the pre-populism period were Germany, Poland, and the United States, and these countries. The statistical significance at 5 percent is reported.

The estimates show that a greater number of students started going to countries that do not have many globally highly ranked higher education institutions. Students also started attending universities in countries that are historically less popular, and the outmigration of students increased over time. These findings suggest that the tendency to seek a foreign education increased not because of a desire to pursue a higher quality education abroad but, probably, because of the intention to use a foreign education as a pathway to long-term migration. Moreover, I used the number of academic publications written by researchers in a country as a proxy for higher education opportunities available in that country. There was no apparent deterioration in the academic publishing of Ukraine compared to its synthetic control after the rise in populism, which also supports the hypothesis that the student migration increased due to longer-term migration rather than better education.

Young citizens may wish to enjoy personal freedoms elsewhere if civil liberties in their origin countries deteriorate due to populism. For instance, Than (2018) reported that young Hungarians complained about the lack of freedoms and considered migration to foreign countries as an option before the 2018 election in Hungary when Viktor Orbán was running the campaign for his third term. Moreover, young people may also want to escape from potentially deteriorating economic opportunities in the origin countries, which could be associated with populism. Indeed, my analysis of the output per capita and the youth unemployment rate shows that Ukraine’s economic outlook negatively diverged from that of its synthetic control countries after 2010 (although the divergence is not statistically significant).

Conclusions

In summary, my analysis shows that the number of people who pursue higher education abroad increases among citizens governed by populist leaders who adopt authoritarian policies. The outmigration of skilled citizens as international students might constitute a threat to the economic outlook of these countries. This is concerning, particularly if these citizens do not return to their origin countries after graduation or if they cut their ties with their origin countries. Such behavior is likely to reduce the potential benefits of international student mobility, such as knowledge spillover and building cultural and business connections between the destination and the origin countries.

References

Abadie, Alberto. and Javier Gardeazabal. (2003). “The Economic Costs of Conflict: A Case Study of the Basque Country.” American Economic Review, 93(1), 113-132.

Demirci, Murat. (2021). “Rising Political Populism and Outmigration of Youth as International Students.” Koc University-TUSIAD Economic Research Forum Working Papers 2123, accessed at https://ideas.repec.org/p/koc/wpaper/2123.html

Than, Krisztina. (2018) “Young Hungarians Weigh Migration Option as Election Nears”. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-hungary-election-youth/young-hungarians-weigh-migration-option-as-election-nears-idUSKCN1HB1JL

Guriev, S. and Papaioannou, E. (2021). “The Political Economy of Populism.” Journal of Economic Literature, forthcoming.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations