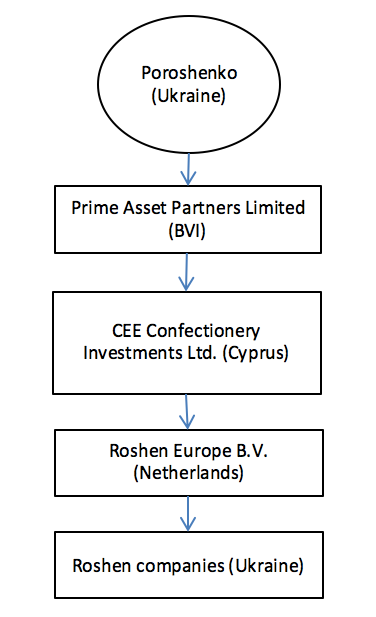

On Sunday, documents, that are now known under the name `Panama Papers’, revealed that in 2014 Ukrainian president Petro Poroshenko became a shareholder of Prime Asset Partners Ltd. incorporated in British Virgin Island, an international offshore destination.

This revelation caused an international and domestic political mini storm, on the margins of the already on-going political crisis in Ukraine. Some accused the president of engaging into entrepreneurial activity (not allowed under the Constitution of Ukraine while in office), failing to disclose ownership of offshore vehicles (as required by law), tax optimization and other irregularities. Others defended the president saying that the offshore legal entity was required to create a “blind trust” or was a part of pre-sale restructuring, both of which could be aimed to fulfil Poroshenko’s electoral promise to sell off his assets.

Whatever were the intentions of the president, he (or his consultants) followed standard Ukrainian business practices. Even if there were violations, they are minor and technical in nature.

The case raises a number of legal and institutional issues, drawing attention to the inadequate exchange control regulation, inflexible corporate and contract law, excessive regulation and unreliable courts in Ukraine. It is unfortunate that so little has been made over the last two years, including by the president, to remedy the situation. This article discusses the most important of these issues, some of which are well covered in press and some of which have been missed.

Before there was … a Ukrainian trust

How did the president manage his assets before creating the offshore company? Were there any violations prior to the current incident? Somewhat unusually, the corporate structure of Poroshenko’s business was simple. His companies were put into Ukrainian investment fund and managed by a local, legally independent financial institution [1]. The benefits of such an arrangement were multifold: a transparent, fully Ukraine based structure [2], technical compliance with limitations on activities of public servants [3],and no tax on the profits if the assets are sold, unless they are further distributed to the beneficiaries.

This simple and transparent structure was changed. As of March 25, 2016, Roshen business is owned by the president from abroad [4].

Why change?

We can think of at least three reasons for this change: setting up a foreign law blind trust, a part of presale restructuring, tax optimization. We now explain all three in more details. All of these reasons are at least in part a consequence of inadequate and outdated legislation in Ukraine.

„Blind Trust” and pre-sale restructuring

The president has made an electoral promise to divest his assets if he is elected. This promise was a response to the public concern about potential conflict of interest between profit-maximization objectives of the business owned by the president and the national interest. Blind trust and selling the assets are both possible mechanisms for the resolution of this conflict.

Blind trusts are frequent international practice. A blind trust holds the assets of a politician while she is in the office. The assets are managed by independent and reputable trustees while the politician has no right to give any orders about how to manage the assets nor receives any information about their performance. The trust contract cannot be „undone” until certain pre-defined events take place (e.g. a person ceases to be a president).

In fact, blind trust is similar to Ukrainian investment fund used by Petro Poroshenko. So, why the change? International reputation of the trustees and legal certainty of foreign jurisdiction can provide additional protection against abuse by the trustees and the politician. In contrast, the Ukrainian institutional safeguards are weak.

Still, one might want to see a hybrid solution with a blind trust established in Ukraine, same as the Ukrainian investment fund of the president. It would be nice to have the fund administered by foreign reputable trustees, subject to foreign legislative protection. Unfortunately, this is not feasible under Ukrainian legislation. First, foreign trustees may not manage Ukrainian investment funds. Second, such a contract governed by foreign law would be at least partially unenforceable in Ukraine or with respect to Ukrainian persons.

Why several companies were established? Setting up a blind trust in a foreign jurisdiction requires at least two foreign entities. One entity is a party to the agreement with the trustees, the shares of another are put into trust. The choice of the location for the entities and other particularities of the structure are determined by multiple factors. First, the jurisdiction for incorporation of the grantor of trust, usually of a common law tradition, should have flexible corporate law, appropriate financial regulations and trust laws permitting creation of a „blind trust”. Second, the choice is driven by (i) the preferences of the management company (Rothschild, in Poroshenko’s case), as it depends on their set-up, as well as by (ii) tax and cost considerations (more reputable jurisdictions cost more).

Why in British Virgin Islands? It is an understandable choice, as jurisdiction would meet the above requirements. But so would be the more expensive United Kingdom, the USA, or the Netherlands, which are not viewed as offshores by general public.

Selling the asset is another way to resolve the conflict of interest. This might have been the most reasonable and simple approach in a properly functioning market economy. Selling a Ukrainian business without “going offshore” is possible, but quite difficult. Ukrainian strict exchange controls, inflexible corporate and contract law, excessive regulation and unreliable courts complicate the logistics of the transaction and scare prospective purchasers driving the price down. Furthermore, Ukraine is in a recession and the buyers who are eager to invest in Ukraine and are familiar with the Ukrainian intricate business environment are far and between. As a result, it might be attractive to restructure the ownership structure of the assets so it is easier to sell them outside of Ukrainian jurisdiction.

Is the structure tax driven?

An alternative explanation is that the offshore company was created to decrease the total tax obligations [6]. Cheating Ukraine of tax proceeds, however, was probably not the aim of the restructuring. Under both old and new corporate structure, profits from the sale of business would not be taxable in Ukraine – there is a tax exemption for the profits of Ukrainian funds and no rules to reach the profits of foreign companies. Nonetheless, to avoid accusations of wrongdoing, the price at which Ukrainian business was transferred to the Dutch holding is important.

Ukrainian tax implications of distributing the funds to Poroshenko as a beneficiary would also be similar regardless of whether it is done through the offshore structure or domestic fund – money will be taxable in Ukraine. Indeed, distributing the profits to Poroshenko would generate tax obligations in Ukraine and would decrease the risk of accusations and public perception of tax optimization.

The overall tax burden of the business sale with the jurisdictions chosen by Poroshenko’s consultants would be quite low. There might be no or limited tax exposure abroad – the BVI/Cyprus/Netherlands structure is well suited for the needs of Ukrainian business thanks to favourable taxation of capital gains and dividends and an excellent double tax treaty between the Netherlands and Ukraine (a benefit for the purchaser). Using “onshore” foreign jurisdictions, though quite possible, would be more expensive.

There is one clear non-tax advantage of using foreign structure – the ability to receive the profits from the sale of business outside of Ukraine. This would reduce exposure to currency and other Ukraine specific risks. Doing so, however, even though legal, would be a politically questionable choice.

Possible irregularities while creating a new structure

There are several additional considerations, some of which have not been discussed in detail in the media and by the public.

NBU licensing

The fool-proof options for a Ukrainian to acquire shares abroad are to get an NBU license to invest or to have the transfer of shares documented as a present from abroad and pay tax on it in Ukraine. A more innovative approach, which would probably stand scrutiny, would be to claim that the shares acquired had no value (for example, because they have no nominal value).

Transfer pricing and settlement for the shares

The price for the shares in Ukrainian companies transferred to foreign holding might have been irrelevant in other jurisdictions – intergroup restructuring is often non-taxable. Not so in Ukraine, where intergroup transfers are treated as a sale, with transfer prices applicable and tax payable if due. We do not know the price in the current case. Selling for nominal value would be a business practice for Ukraine. Especially in cases such as this one, when any profits realized would be tax exempt, and thus Ukrainian transfer pricing would not apply.

A related question is settlement for the corporate rights purchased by the Dutch holding. Has the consideration been already paid to the investment fund? Generally, the closer the price to the market value, the more difficult it is to find the funds for making the intergroup settlements. If the payment was made, what is the sources of the funds (the nominal value of the shares in the foreign companies is negligible). A loan? Funds from a foreign company we are unaware of? Or is the debt outstanding? This would be the cleanest option. After the sale, the proceeds could be transferred to the “Prime Assets Capital” in settlement of the debt for the intergroup transfer of the shares. Thus way, the sales proceeds would end up in Ukraine, where they are due.

Settling a company while in highest office

It is not clear whether creating a new company by the president, even though inactive, should qualify as engaging into entrepreneurial activity, prohibited under the Ukrainian Constitution. The law is silent, so is court practice.

Anti-trust clearance

Another question to ask is whether Rothschild received antitrust clearance from Ukrainian competition authorities, as it probably should have if the blind trust was created and the control passed from the asset management company “Fusion Capital Partners” to the international manager. The president is still indicated as the ultimate beneficiary of the business. This, however, may or may not mean an anti-trust violation – the practice for disclosure of such arrangements is still developing in Ukraine.

Failure to declare

The lawyers of Petro Poroshenko and his other supporters did a good job trying to explain away his failure to declare the BVI company in his annual declarations. Still, it was clearly a violation. It would have been material if the restructuring was completed in 2014 or 2015 covered by the declarations filed. A failure to disclose a parent company holding the president’s major business asset would have been impossible to justify. But the transaction was completed in March 2016. At least as of 25 March 2016 the information about ROSHEN EUROPE B.V. (the Dutch company) replacing the investment fund was entered in Ukrainian register, with Poroshenko disclosed as a beneficiary.

A possibe explanation could be that while the foreign structure was being created (obviously by the lawyers and not the beneficiary) and blind trust negotiated, the offshore companies were viewed for what they practically, even though not legally, were, namely a technical instrument with no value until used. An error of judgement, understandable, but still an error.

With great thanks to Integrites lawyers who share the opinion that the president’s business structure is not uncommon, but believe that the solution does not appear to be resistant to the public scrutiny and, therefore, explanations of the president’s Ukrainian counsel are not convincing.

Notes

[1] Non-diversified investment fund “Prime Assets Capital” is managed by asset management company “Fusion Capital Partners”.

[2] You can find financial statements, auditors’ reports and certain other information on “Prime Assets Capital” here and here.

[3] The beneficiary could retain informal management control over the companies.

[4] See the outline of Roshen business based on the information from the companies register.

[5] The agreement establishing the trust on 14 January 2016 was signed by Prime Asset Partners Limited incorporated in BVI.

[6] Profits of the president’s business are taxed in Ukraine on the level of Ukrainian companies (Roshen is ranked no.74 among top taxpayers, with tax payments in 2015 exceeding 1,3 bln UAH. Individually, Poroshenko declares income received as dividends, which is taxable in Ukraine (in 2014, for example, he declared over 345 million UAH under the category dividends and interest). Thus, the concern is not that his operations are not taxed at all, but that the president might have intended to avoid paying tax in Ukraine on the capital gains from the sale of his business.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations