The new Law of Ukraine On Vocational Education creates extensive opportunities for cooperation between education institutions and employers. From now on, every employer can move from the role of a passive consumer to that of an active participant in shaping the specialists they require.

In early September, the new Law on Vocational Education (4574-IX) entered into force. It introduces a comprehensive modernisation of cooperation between vocational education institutions (VEI) and employers. New structured, contractual, and institutionally formalised mechanisms have been introduced to enhance the relevance, quality, and sustainability of vocational training. Partnership with business is no longer an additional option but an essential component of the governance, financing, and implementation of vocational education (VE) programmes.

A key innovation is the establishment of supervisory boards within VEIs (Article 42). These boards must operate on a parity basis between the institution’s founder and employers, and their powers include approving institutional strategies, endorsing financial plans, and initiating audits. The founder must review, and the director must implement supervisory board decisions adopted within their mandate. This step strengthens quality of governance and transforms employers from external, potential partners into active participants in the institutional development of colleges, VEIs, and training centres.

The law increases competition in the vocational training market by stipulating that work-based learning (WBL) with the option of having qualifications certified in a qualification centre does not require a licence (Article 44). This means that private-sector actors will also be able to provide training services, offering potentially more attractive learning opportunities for adults e.g., short-term courses, direct interaction with a potential employer, and guaranteed employment etc.

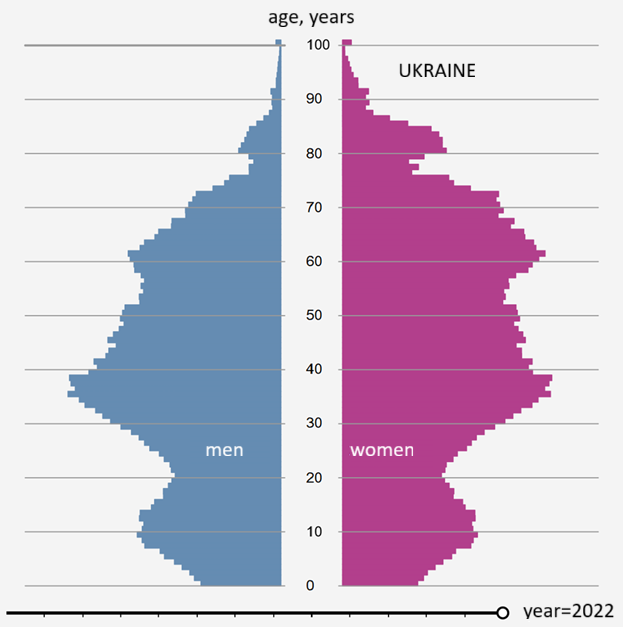

In 2022, the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine (MoES) encouraged VEIs to begin training and retraining adults through Law 2312-IX (which became null and void after the new Law on Vocational Education entered into force, as its provisions were incorporated into the new legislation). This law enabled individuals to acquire professional qualifications without simultaneously completing general secondary education and to receive free vocational training multiple times during their lifetime (on condition of having two years of insurance contributions after each training cycle and at least a three-year interval between them). However, only a limited number of VEIs made use of this opportunity. Most providers continue to focus primarily on young learners. At the same time, the age-gender structure of Ukraine’s population in 2022 (Figure 1) highlights the need to shift attention towards adults aged 35-60.

Figure 1. Age-gender structure of the population

Source: State Statistics Service of Ukraine

For graduates of VEIs or professional training courses who studied at public expense, mandatory independent assessment of learning outcomes in a qualification centre is being introduced (Articles 11-12). Graduates will be able to choose the assessment centre themselves. This approach aims to improve training quality.

Qualification centres will operate as independent institutions responsible for assessing learning outcomes. Separating training provision from assessment is expected to help identify and remove from the system those providers delivering low-quality training. Their identification will be based on persistently poor learner performance during final qualification examinations.

Education institutions may establish their own qualification centres. However, such centres must, first, be institutionally separated from instructional activities and, second, may assess learners from their “parent” institution only in exceptional cases (for example, when no other qualification centre exists in the region or when available centres are not adapted for persons with special educational needs).

Qualification centres are also expected to offer services to businesses by providing transparent verification or certification of the skills of potential or current employees.

A significant innovation is the introduction of standardised cooperation agreements between VEIs and legal or natural persons (Article 69). Such agreements, valid for up to five years, may cover practical training, dual education, equipment modernisation, curriculum development, and employment support. All resources obtained under such agreements must be used for the purposes specified in the contract, and templates approved by MoES will help reduce legal and administrative risks. This is expected to formalise previously informal arrangements and replace them with predictable, long-term contractual relationships.

Tripartite vocational education councils will be established under regional state administrations, consisting of representatives of public authorities, employers, and VEIs. Their mandate is to develop proposals for optimising the regional network of VEIs and to provide recommendations ensuring that training programmes correspond to labour market needs (Article 43). This mechanism ensures that businesses influence regional education policy rather than participating only in isolated initiatives.

The dual form of VE finally receives full legislative recognition (Article 14). Learners will have the opportunity to pursue individual learning pathways. An employment contract between the learner and the employer will now be concluded, combining all state guarantees, rights, and responsibilities of VEI learners with comprehensive occupational safety requirements. The development of dual education will encourage employers to identify and train future employees at early stages of their career trajectories.

VEIs now operate as state, municipal, or private entities, acquire the status of Centres of Vocational Excellence (designed to support the development of specific economic sectors by integrating educational, research, and innovation activities), and join technoparks, clusters, business incubators, innovation centres, and similar structures (Articles 31-32). Such diversification will enable VEIs to choose their development strategies and participate more flexibly in partnerships, joint ventures, and innovation projects with employers and investors.

The law significantly strengthens the financial VEIs’ autonomy (Articles 61-66). They will now be able to attract funding from various sources, place funds on deposit, use leasing instruments, receive donations, and participate in grant programmes. The new funding formula will account for labour market demand for qualifications, and institutions will be able to expand the range of paid services they offer. The law also clarifies options for long-term asset management (Articles 66-68), including leasing the entire property complex of an education institution (with supervisory board approval), transferring an institution into the management of a legal entity under a standard agreement, and updated rules for leasing individual assets.

For the first time, the law addresses student self-governance and its role in addressing academic and welfare issues (Article 30), defines the right of an individual to study along an individual learning pathway (Article 8), and expands institution-level autonomy (Article 34). VE thus becomes more responsive to the needs of all participants in the learning process.

Overall, compared with the 1998 Law, the 2025 reform creates an enabling environment for sustainable partnerships between vocational education and business, while strengthening the system’s capacity to respond to current and future labour market needs.

Photo: depositphotos.com/ua

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations