VoxCheck has been monitoring Russian disinformation in six European countries for almost two years. In this article, we talk about the database of Russian disinformation called “Propaganda Diary,” the main results of monitoring, and the most dangerous trends in pro-Russian rhetoric.

After February 24, 2022, Kremlin disinformation campaigns about Ukraine in the European information space reached unprecedented scales. This created the need to build resilience to information attacks in key audiences for Russian propaganda. The first step was systematic monitoring of disinformation narratives in each individual country. Since the beginning of the full-scale invasion, the VoxCheck team has been monitoring pro-Russian media in six countries: Germany, Italy, Poland, Czechia, Slovakia, and Hungary.

“Propaganda Diary” database

VoxCheck monitored media outlets in European countries and analyzed narratives about Ukraine disseminated by these media. Mostly, identified fakes and manipulations were in line with the main narratives of Russian disinformation campaigns. Every month, the VoxCheck team published reports on the monitoring results. All results are also reflected on the “Propaganda Diary” database website.

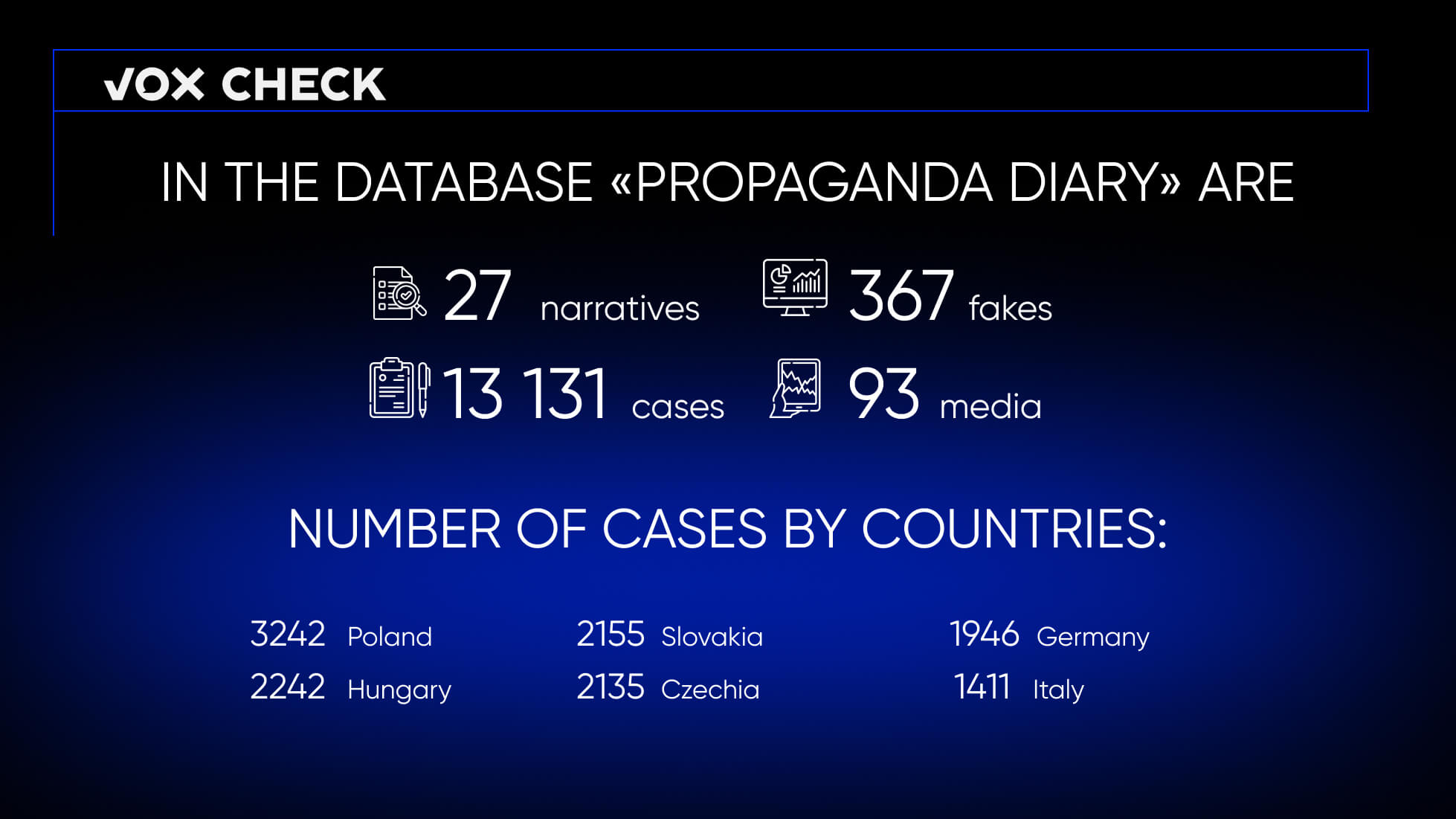

To identify cases of disinformation, VoxCheck employed weekly manual monitoring of a selected list of online resources. The database consists of over 13,000 overtly fake or manipulative messages, which we refer to as disinformation cases. To classify them, we grouped all cases with a common theme into fakes. From these fakes, we formed narratives based on key shared messages. In other words, various cases of disinformation serve as examples of one or several fakes, and different fakes are examples of one disinformation narrative.

What else is in the database?

- A list of all the media we monitor in each country.

- ‘White’ and ‘black’ lists of media in each individual country: resources on the white list are reliable sources providing credible information about Ukraine, while sources on the black list regularly disseminate fake narratives about Ukraine.

- Dynamics of fakes: a review of trends for each month in the years 2022-2023.

- The database has nine language versions and can be downloaded in its entirety, with all cases, in any language version.

Results of monitoring

We identified 27 disinformation narratives and 367 fakes spread across 93 media outlets in various countries. The overall number of disinformation cases from February 24, 2022, to October 2023 is 13,131. Notably, there was a significant increase in cases in each country in 2023: from February 24, 2022, to January 2023, 4,836 cases were identified, averaging 403 cases per month. However, from February to October 2023, there were 8,296 cases, averaging 920 publications per month.

Results of the monitoring of Russian disinformation in Europe

The majority of disinformation about Ukraine was disseminated by media outlets in Poland (3242 cases), Hungary (2242), and Slovakia (2155). The three most popular narratives were “The West controls Ukraine and uses it for its own purposes” (1584), “The actions of Ukraine and the West forced Russia to start the war” (1347), and “Nazism in Ukraine” (1322).

The first narrative, “The West controls Ukraine and uses it for its own purposes,” is well-known to many Ukrainians due to the activities of Medvedchuk: pro-Russian forces have been spreading the idea of “external control over Ukraine” for years. However, European media outlets do not always resort to direct quoting of Russians or collaborators. To promote this narrative, they invite “respected speakers” (actually pseudo-experts), such as Americans Jeffrey Sachs or Scott Ritter, who predict that the U.S. will turn Ukraine into a “new Afghanistan” — a failed state whose citizens “will die for America’s geopolitical goals.”

Within the narrative “The actions of Ukraine and the West forced Russia to start the war,” typical justifications for aggression were voiced, such as “Ukraine bombed Donbas for 8 years,” “NATO expansion threatens Russia,” “Ukraine was preparing to attack Russia first,” “The West deceived Russia,” and so on. Blaming the victim (‘they are to blame themselves!’) is a classic tactic used by Russians, repeatedly employed against various countries affected by Russian imperialism.

Pro-Russian propagandists also continue to seek “Nazis” in Ukraine. If before the full-scale invasion, attacks were mostly directed against individual Ukrainian politicians or military figures, such as the Azov battalion, in 2022-2023, almost every Ukrainian ready to resist Russian aggression is labeled as a Nazi.

Disinformation trends in Europe

The first trend is the persistence of pro-Russian narratives. The main narratives of pro-Russian media in Europe have remained unchanged for almost two years. To the extent that some sources continue to repeat fakes that were invented as far back as 2014. For example, Robert Fico, the new Prime Minister of Slovakia, repeated a fake from Russian propaganda during the election campaign, claiming that “the war in Ukraine started in 2014 when Ukrainian Nazis and fascists began killing Russians in Donbas and Luhansk.”

Propaganda seems frozen in the past: in pro-Russian publications, the Revolution of Dignity in Ukraine is still considered a state coup, Russian aggression since 2014 is labeled a civil war, and the “Azov” unit is referred to as a battalion, even though at the beginning of the full-scale invasion, it was already a regiment, and it has now expanded to a brigade. The proof of the persistence of narratives lies in the three aforementioned most massive narratives during the monitoring period. All of them have been propagated by Russia since at least 2014. So, propaganda does not necessarily have to be sophisticated and skillful; it is enough to frequently repeat fabrications, especially when the carriers of falsehoods are pro-Russian politicians, opinion leaders, or media.

On the other hand, pro-Russian media sometimes update old narratives through new information triggers. For example, the war between Israel and HAMAS: fakes emerge about how weapons found in HAMAS fighters were supplied by Ukraine or about how Israel fabricates war crimes, “just like Ukraine did in Bucha.”

Another example is the revitalization of narratives through new war crimes. Russia commits war crimes daily in Ukraine. Almost every crime is accompanied by fakes that align with the old narrative “Russia does not commit war crimes in Ukraine”: “Russia is not involved in the destruction of the Kakhovska Hydroelectric Power Station,” “Ukraine stages events to accuse Russia of crimes,” “the deportation of Ukrainian children to Russia is not a war crime.”

Therefore, despite the persistence of narratives, monitoring European media remains relevant, as it is necessary to identify new fakes about Ukraine and respond to them.

The second trend is strengthening of disinformation dissemination by pro-Russian and Eurosceptic political environments. The most dangerous situation arises in those countries where politicians directly or indirectly advance the Russian agenda — Poland, Slovakia, and Hungary. In the first two, parliamentary elections were held in the fall of 2023, during which pro-Russian themes were echoed: calls to cease or reduce support for Ukraine, and discriminatory statements regarding Ukrainian refugees in Europe. Meanwhile, in Hungary, a pro-Russian leader has been in power for years and is one of the disseminators of Russian propaganda in the EU. For example, in October 2023, during a meeting with Putin, Viktor Orbán referred to the Russian invasion as a “military operation.”

As a result, European media may spread disinformation by quoting politicians from their own countries if they do not include fact-checking of political statements in their publications. Moreover, when pro-Russian themes are voiced at a higher level, such statements gain more legitimacy in the eyes of the audience.

The third trend is that propaganda hits harder on vulnerable topics related to Ukraine and the Russian invasion. Pro-Russian media search for issues that are most sensitive to the European and Ukrainian audience: corruption in Ukraine, risks of decreasing support for Ukraine in the West, and expectations regarding a counteroffensive. Of course, disinformation outlets don’t just acknowledge these problems; they extract them from context, distort, exaggerate, create conspiracy theories or information-psychological operations based on these stories, and direct them against various audiences. Thus, a neutral statement like “there are problems with corruption in Ukraine” turns into “Ukraine is the most corrupt country in the world” in the world of propaganda, “All Ukrainians are corrupt,” or “Ukraine is an incapable state.”

Conclusion

In Europe, there is no information space that has escaped Russian propaganda’s penetration. The quantity of disinformation varies depending on the country, political circumstances, and the activity of pro-Russian media. However, VoxCheck identified common trends in all six countries.

Basic Russian narratives remain constant to such an extent that the most massive narratives in European media are those invented by Russia back in 2014: the West’s total control over Ukraine, justification of aggression against Ukraine, and “Nazism in Ukraine.” Pro-Russian resources mimic what Russian state media does: construct an entire parallel reality based on references to old stories. However, there is an advantage for the creators of fakes in this: what is repeated more frequently and intensively is better remembered and more effectively ingrained among the audience. Meanwhile, new fakes emerge within these narratives as propagandists react to current information triggers.

The spread of disinformation about Ukraine is facilitated by a pro-Russian or Eurosceptic political environment. The highest risks are in countries where politicians have directly or indirectly promoted anti-Ukrainian statements (Poland, Slovakia, and Hungary). Media outlets have also joined these information attacks when quoting politicians or participating in political discussions. The most dangerous fakes remain those that undermine the audience’s confidence in supporting Ukraine, such as false information about military actions, Western aid, the fight against corruption, or reforms in general.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations