The case of Ukraine shows that privatization of assets is not enough, by itself, to improve the market performance. Institutional reforms that reduce uncertainty and improve protection of rights are also a pre-condition for economic productivity gains. Adoption of law proposals that simplify and lower the cost of registration of rental rights, resolving issues with legal status of land parcels, consolidation of land ownership to the level of cultivated field and, ultimately, lifting the Moratorium could finally provide certainty and security to the rights of owners, tenants, state and investors.

The current debate about lifting the Moratorium for sales of agricultural land and regarding the land reform in general touches directly and indirectly one of the core issues of agricultural development in Ukraine: security of property rights for land and its implications for productivity of agricultural sector. Does the rental market in its current design provides sufficient security and support or suppress the agricultural productivity? We argue and provide evidence that tenancy in Ukraine is less secure than land ownership. These relatively insecure tenancy rights lead to underinvestment, shift in crop mix and cause losses in productivity and value added in agriculture.

Key points of land reform in Ukraine

In addition to traditional sources of uncertainty (price and weather), agriculture in Ukraine faces an additional uncertainty factor – changes in the institutional protection of property rights for land.

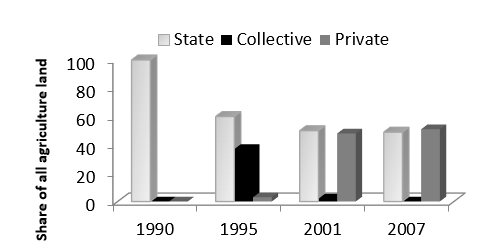

The country had experienced some major changes in institutional regulation as a part of the transition from a centrally planned to a market economy. While in 1990 all land belonged to the state, by the end of 1990s, most of the state farms had been reorganized into collective farms, which owed about 40 percent of agricultural land (Figure 1), and then land was transferred to private ownership as a part of the privatization process. However, most individuals, who received agricultural land during this time, had no working capital, equipment, or capacity for independent farming. Many of these new owners had only two options for using the land: to keep it idle or to rent it out (in most cases to managers of the former collective farms). Besides, poor or non-existing privatization records and unclear transaction procedures were pervasive and numerous cases of land grabbing, manipulation and falsification had been recorded [2].

Figure 1. Changes in Land Ownership Structure

Source: State Agency for Land Resources of Ukraine (2014)

To regulate the land use and land transactions, the Parliament of Ukraine adopted a new Land Code in 2001. However, a ban on sales and conversion of agricultural to non- agricultural land (the Moratorium) was imposed until January 1st, 2005. It had been extended five times since then and is expected to be extended further in 2016 (Editor’s note: On November 10 in the evening session Parliament adopted the Law «On amendments to section X Transitional provisions of the Land code of Ukraine concerning prolongation of prohibition of alienation of agricultural land» (draft law №3404); law provides extension of the moratorium on sale of land of agricultural appointment till January 1, 2017). These extensions contribute to institutional uncertainty in the agricultural sector as rights of tenants, land owners and investors may be changed by future institutional design of the land market.

A more recent example of imposing unexpected restrictions on the land market is the Law of Ukraine adopted by the Parliament on February 12, 2015. This Law imposes seven years as a minimum length of agricultural land rental contracts.

As a response to such institutional uncertainty, several coping strategies have been adopted by land owners and producers. These strategies include informal rental transactions, keeping land idle or short term rental contracts. All of them are associated with a decline in agricultural productivity and may also lead to unsustainable land use.

Poor protection of property rights of tenants vs. owners decreases incentives to invest in general and in land improvements in particular as the institutional uncertainty reduces expected net present value of returns to investments. The option value for any investment becomes particularly high, as investors would prefer to have resources available by the time when the land sales market is established. In such environment, investments in crop enterprises with relatively short return (e.g. annual crops) would be a safer scenario than investments in crop enterprises with a longer return (e.g. perennials).

Is the crop structure efficient in Ukraine?

To provide an evidence to the above statement about insecure rights of tenants and under-investments, we developed a simple test. We compare the changes in share of perennial crops (fruits, berries, grape) with respect to changes in the share of rented land for large and medium farms in Ukraine during 2004-2012. If the rights are insecure we would observe a systematically lower share of investment intensive perennial crops at tenant farms. In order to rule out an alternative explanations that the tenant farms may have a better access to capital, technology and other resources, a similar comparison was done for grains and oil crops. If not the property rights, there should be no difference in crop mix across the tenant and owner cultivated farms. In policy analysis, such approach is known as difference-in-difference.

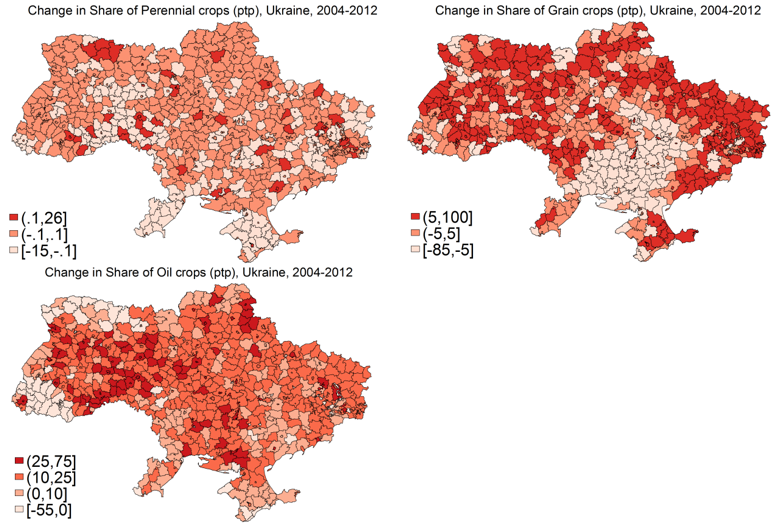

The State Statistics shows that a significant transformation in the crop mix was observed between 2004 and 2012. An average share of oil crops, led by sunflower, more than tripled (from 8 percent to 25 percent) and the total land area for these crops has more than doubled. Strong international prices and increased oilseed productivity seem to be responsible for this shift. About 50 percent of land cultivated by medium and large farms has consistently been used for production of grain crops. However, the perennial crops show a very different tendency. Both the share and total land area under perennial crops contracted and the number of producers has declined. The average share of cropland decreased from 0.66 percent to 0.48 percent and the total area declined from 74.6 thousand hectares to 31.5 thousand hectares. The retail market has responded by an increase in import of fruits. During the same period, profitability of perennial crop production has increased almost 6 times and productivity has more than doubled. In 2012, the average profitability of production for perennial crops was about 1,770 USD per ha while for the oil crops and grains it was 770 USD per ha and 515 USD per ha, respectively. It would be reasonable to expect that in a longer run the share of perennial crops would increase. Instead it shrunk. The observed deviation from what could be an optimal crop mix in terms of the value added, may point to some market imperfections in input or output markets for perennial crop production.

During the same period, the total share of rented land has increased from 92.96 to 94.38 percent for farms above 200 ha. Are these changes related? To answer this question we analyzed the data by the State Statistics with some advanced methods of policy analysis [3].

Figure 2. Change in the crop mix, Ukraine, 2004–2012

Source: State Statistics Form 50 AG

Possible impact of land market imperfections

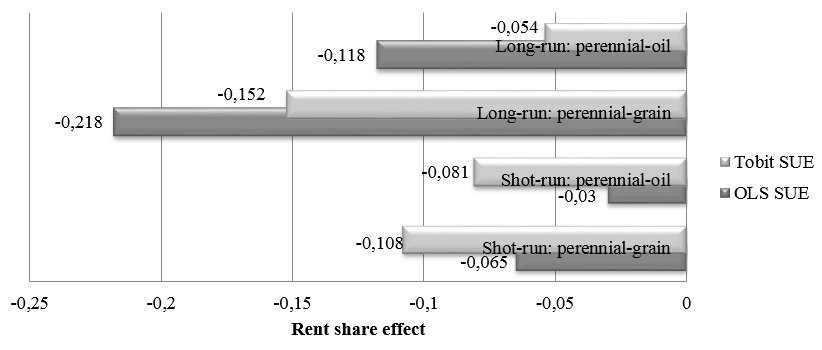

The obtained results show the effect of insecure rights of tenants in short-run (1-4 years) and long-run on investments in perennial crops. The difference in the effect of rental market between perennial and annual crops points to a strong negative effect (Figure 3). It means that tenant farms systematically prefer less risky annual crops. Alternative explanations related to prices, regional specifics and common changes at national level are excluded with statistical methods.

Figure 3. Effect of rent share on the difference in perennial and annual crop mix

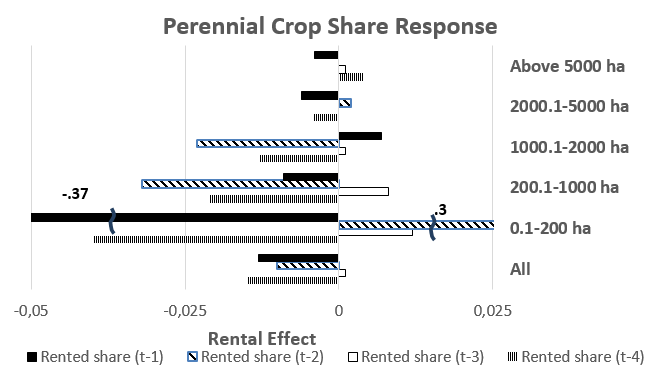

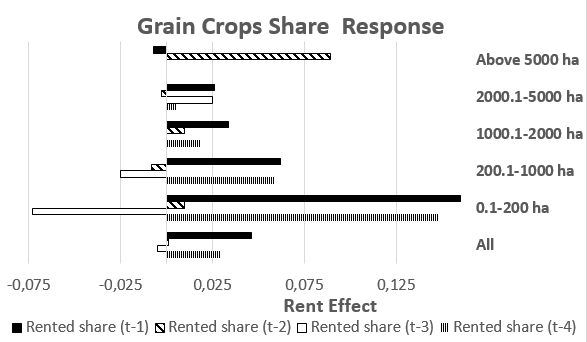

A striking difference in the negative effect of rental market is observed across the farm sizes. Figures 4 and 5 illustrate that the effect is most negative for smaller farms. The effect of rental market on larger farms and the difference of this effect between perennial and annual crops is very small, which would be expected when rights of tenants are well protected. Such differentials in the effect of property rights might be explained by the market and political power enjoyed by larger farms as well as access to better legal services available to them.

Figure 4. Effect of rent share on share of perennial crops

The total difference between the short-run effects for perennials and grains is largest for farms below 200ha (-0.34 percentage points decrease in share of perennials) and smallest for the farms cultivating between 2,000 ha and 5,000 ha (-0.06 percentage points). A similar pattern is observed for perennial vs. oil crops.

Figure 5. Effect of rent share on share of grain crops

To summarize, the decrease in the observed investment in perennial crops (and likely other long-term investments in land quality and other agricultural projects) is largely explained by the insecurity of property rights of tenants associated with unfinished land reform in Ukraine and multiple extensions of the moratorium.

How much does this loss cost the country?

If we estimate the losses as the difference in value added per hectare between perennials and the highest alternative among the annual crops (oil seeds) – profitability in 2012 was 1,772.87 and 774.25 USD per ha respectively – then the loss is about 1,000 USD per hectare. Over 2004-2012 period Ukraine lost about 43 thousand hectares of perennials, which we can now attribute to the insecure property rights. It implies that Ukraine loses about 43M USD per year of value added on under-investments in perennial crops only. Underinvestment in dairy, vegetables, greenhouses and irrigation would increase the size of these losses further. This loss is distributed differentially across the farm sizes and most of these losses are faced by the smaller farms.

Strategies to decrease the negative influence

The case of Ukraine shows that privatization of assets is not enough, by itself, to improve the market performance. Institutional reforms that reduce uncertainty and improve protection of rights are also a pre-condition for economic productivity gains.

The remedies for this uncertainty are primarily of political nature. Adoption of law proposals that simplify and lower the cost of registration of rental rights, resolving issues with legal status of land parcels (e.g. unclaimed inheritance and privatization shares (pays), land in collective property), consolidation of land ownership to the level of cultivated field and, ultimately, lifting the Moratorium could finally provide certainty and security to the rights of owners, tenants, state and investors. Together with improvements in law enforcement and decrease in corruption, these law proposals should provide long needed incentives for the development of Ukrainian agriculture and rural areas in general. Finally, resolving uncertainty regarding, the land market would stimulate longer-term lease agreements and make investment incentives for tenant farms more similar to those for owner farms.

Notes

[1] The full version of the background paper. It is forthcoming in the Journal of Comparative Economics

[2] Report of the Ukrainian Parliament Commissioner for Human Rights, 2004

[3] For more details on methods see the full version of the background paper

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations