Over 1,500 Ukrainian educational and research organizations have been seized by Russia after 2014, including 289 higher education institutions such as universities, institutes, colleges, and their branches. These institutions are now exploited to promote Russia’s geopolitical agenda through propaganda, justification of Russia’s annexation of Ukrainian territories and assimilation of Ukrainian population in occupied regions.

Russian aggression against Ukraine, which started with the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014 and intensified with the full-scale invasion in February 2022, has profound and multifaceted impacts on the Ukrainian academic sector. Russians not only destroy the physical infrastructure of Ukrainian universities and scientific institutions and kill Ukrainian scientists, but also disrupt educational and research processes, including by displacement of thousands of students, professors, and researchers.

According to UNESCO (2024), Ukraine’s public science sector has about 450 research institutes and 140 universities. From February 2022 to January 2024, 1,443 buildings belonging to 177 institutions were damaged or destroyed. To restore public research infrastructure, Ukraine needs $1.26 billion, including $980.5 million for universities, which produce 52% of public research output. Official Ukrainian estimates are even higher: according to the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine, as of February 24, 2023, as a result of shelling and bombing, 2,711 educational institutions were damaged and 440 were destroyed (MESI, 2023).

Despite the significant attention to the damage Russia has done to Ukrainian science and academia, there is one relatively unexplored issue: Ukrainian academic institutions stolen by Russia. Since the illegal annexation of Crimea in 2014, dozens of universities, research institutions, and their infrastructure, including academic journals, have been appropriated by Russia. The problem significantly worsened after the start of the full-scale invasion because Russia occupied more territories and claimed as annexed more regions: in addition to Crimea, Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia, and Kherson regions (although it completely controls only Crimea).

According to Kubijovyč (2022), as of 2013, there were about 100 scientific institutions that implemented fundamental research in Crimea, including 20 branches of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. They all were stolen by Russia after the annexation of Crimea, including famous Crimean Astrophysical Observatory, the Marine Hydrophysical Institute, the Institute of the Biology of Southern Seas of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, the National Institute of Grape Growing and Wine-making ‘Maharach’, the Institute of Agriculture of Crimea, and many others.

Most of these research institutes were appropriated by the Russian Academy of Sciences, which is currently under the Ukraine’s, EU and US sanctions. Despite this, international publishers and databases recognize these institutions as Russian and cooperate with them. For example, Scopus page of Russian Academy of Sciences includes Crimean Astrophysical Observatory, Black Sea Hydrophysical Proving Ground, Marine Hydrophysical Institute, “All-Russian National Research Institute of Viticulture and Winemaking” ‘Magarach’, A. O. Kovalevsky Institute of Biology of the Southern Seas, Nikitsky Botanical Gardens – National Scientific Center of Russian Academy of Sciences, Institute of Crimean Archaeology (Scopus, 2024). All of these are Ukrainian institutions looted by Russia in the occupied territories.

The most recent official data

There is no unified list of stolen universities, and the official data is scattered. To obtain the latest official data, we sent an inquiry to the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine (MESU), which forwarded our inquiry to the State Enterprise “Inforesurs”. This enterprise is in charge of the Unified State Electronic Database on Education (USEDE) – an automated system for collecting, certifying, processing, storing, and protecting data, including personal data, on providers and recipients of educational services in Ukraine.

“Inforesurs,” based on USEDE data, created two lists of educational institutions: one includes those located in Luhansk, Donetsk, Zaporizhia, Kherson, Kharkiv regions, and Crimea, and the second one includes institutions relocated from those regions to government-controlled areas. Note that this data may be incomplete since some institutions may have not provided the relevant information to USEDE. This doesn’t change the fact that marking Ukrainian territories as Russian violates international law.

Overall, 1,516 educational institutions were located or relocated in 2014-2024 from the Luhansk, Donetsk, Zaporizhia, Kherson, Kharkiv regions, and the Autonomous Republic of Crimea. This number includes all types of educational facilities and education management authorities, from institutions of higher education to departments of education of city councils (Table 1). It’s important to understand that even if an institution relocated, this means that its buildings, some part of equipment and other material assets remain in the occupied territories. Some professors or students may have remained too for different reasons.

Table 1. Educational institutions and education management authorities located in occupied territories as of January 1, 2025

| Type of educational facility | Number, units |

| Institution of Higher Education | 407 |

| Institution of Postgraduate Education | 1 |

| Institution of Vocational (Professional-Technical) Education | 448 |

| Institution of Professional Pre-Higher Education | 152 |

| Other Institutions | 2 |

| Other Educational Institution Providing Vocational (Professional-Technical) Education | 78 |

| Scientific Institute (Institution) | 35 |

| Education Management Authority | 393 |

| Total | 1516 |

According to USEDE methodology, “institutions of higher education” include not only universities but also academies, institutes, branches, and faculties of the universities and colleges. In this paper, we use the term “universities” for all institutions of higher education.

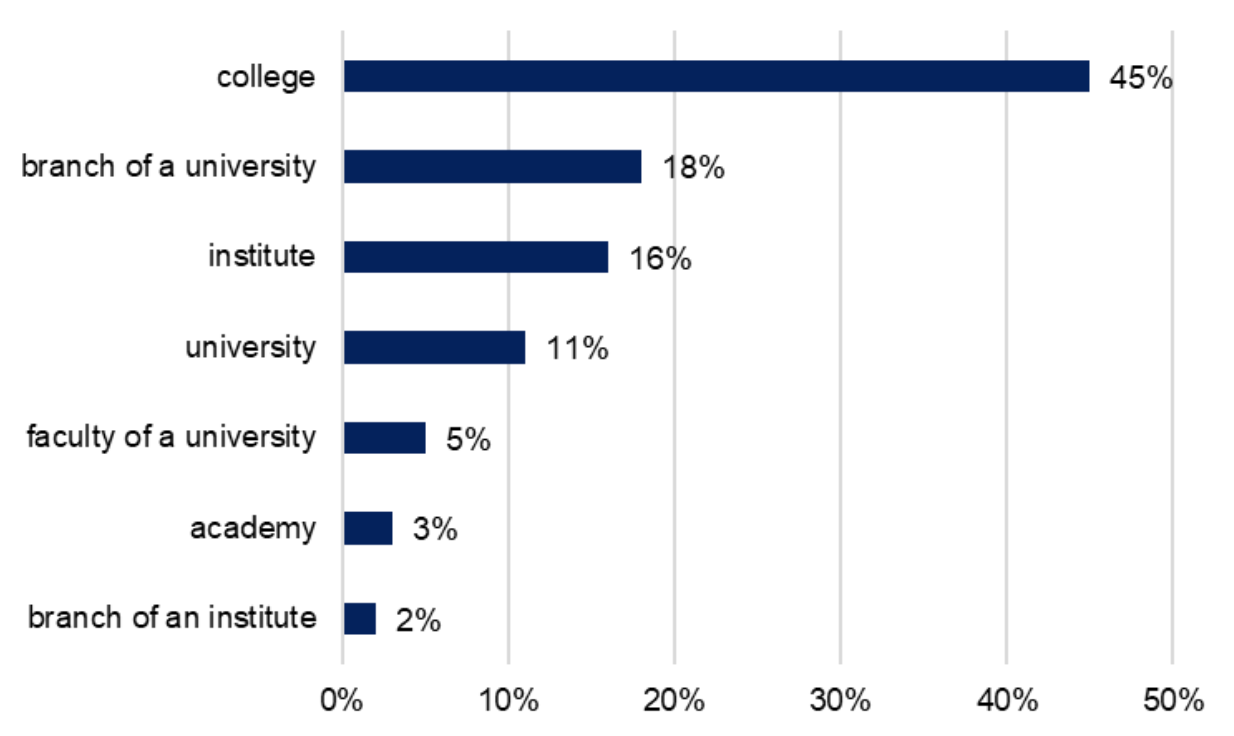

USEDE classifies institutions in the occupied territories into those that “moved to controlled territory” and those that are “blocked.” If an institution has one of these statuses, we identify it as stolen. We exclude institutions that were blocked for some other reasons than occupation. For example, some institutions were closed before the full-scale invasion due to reorganization. We also exclude institutions located in Kharkiv and Kherson regions that were occupied in 2022 but now are under the control of the Ukrainian government. Other institutions, irrespectively of whether Russia closed, reorganized or just renamed them, are labeled as stolen. Altogether there are 289 stolen institutions of higher education in the occupied territories. Their distribution by type is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Structure of stolen institutions of higher education by type, %

Source: USEDE, own calculations

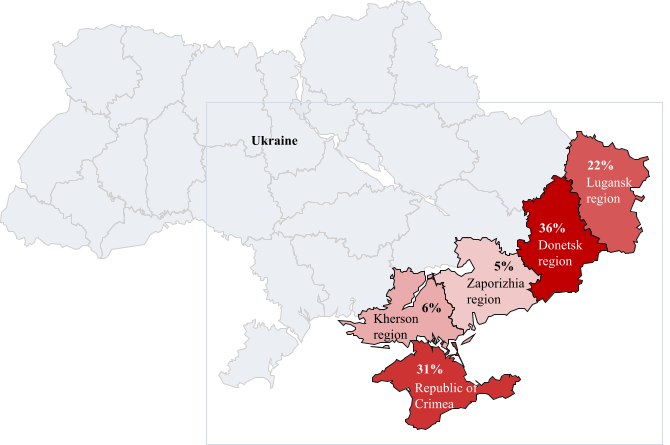

As we see from Figure 1, 131 institutions (45%) can be classified as colleges, 53 (18%) as branches of universities. 45 institutions (16%) are institutes, and 31 of them are universities (11%). Figure 2 shows the geographical distribution of stolen institutions of higher education. The regions that suffered the most are Donetsk (105 institutions were stolen by Russia), the Republic of Crimea (88), and the Luhansk region (64). Kherson and Zaporizhia regions have lost 18 and 14 institutions of higher education respectively.

Figure 2. Geographical structure of stolen institutions of higher education

Of the 289 stolen institutions of higher education, 242 are “blocked,” i.e. they do not implement any activity, and 53 “moved,” i.e. some of their assets and people were relocated to government-controlled areas. Six “moved” institutions were “blocked” later, i.e. they do not exist anymore.

How Russia uses stolen Ukrainian universities against Ukraine

The Hague Convention (1907) imposes on occupying powers the responsibility to respect and maintain the institutions and services on occupied territories, including educational establishments. However, it’s quite typical for occupants to violate provisions of international conventions. According to UNESCO (1945), during WWII, in countries like Czechoslovakia and the Netherlands, universities faced closures, staff dismissals, and strict censorship.

Redzik (2004) explored the case of Polish universities during the Second World War and found that the German occupying forces systematically suppressed Polish academic life by closing universities, confiscating their assets, and persecuting faculty and students. Occupants aimed to suppress national identities and resistance by controlling educational content and access to education. Under Soviet occupation, Poland experienced a nationwide assimilation to Soviet educational and cultural standards too.

Since Russia is a descendant of the Soviet Union, no wonder that it uses the worst practices from both: the German occupying forces and the Soviets.

Stolen academic institutions are widely used for the purposes of Russian propaganda, justification of annexation of Ukrainian territories, and assimilation of the Ukrainian population in the occupied territories. The worst thing is that international organizations and publishers support this aspect of Russian propaganda, as we discuss below: looted Ukrainian universities appear as “Russian” in international journals, and the International ISSN Centre legalizes stolen Ukrainian journals. We consider these two issues below.

Issue #1. Ukrainian Universities/territories are marked as Russian by international publishers and academic organizations

Plastun et al. (2024a), using the Scopus database, showed that there is a systemic issue of misrepresenting Ukrainian territories as part of the Russian Federation in academic publications. The fraction of such publications depends on the duration of Russian occupation and the time of annexation. It is over 90% for universities in Crimea, which were temporarily occupied and annexed by Russia in 2014, versus 50% for Donetsk and Luhansk temporarily occupied in 2014 but claimed as annexed only in 2022. For Mariupol (temporarily occupied by Russia since 2022), it was zero in 2022 rising to 4% in 2023, which is an unfortunate trend. An interesting case is Kherson, which was occupied for a few months in 2022. No publications affiliated Kherson with the Russian Federation in 2022 and 2023, but in 2024 (two years after it was liberated by Ukraine), two articles with this affiliation appeared in Scopus-indexed journals (1, 2).

Thus, international journals accept publications with problematic affiliations. The majority of such publications are published in Russian journals by Russian publishers. But over 30% of the publications with problematic affiliations in 2023 were propagated through international publishers, heavily dominated by Springer Nature/Pleiades (Germany/USA), followed by MDPI (Switzerland), EDP Science (France), IEEE (USA) and Elsevier (Netherlands). Individual publications appeared in ASV Publishing, CSIRO, MM Publishing, Science Press, Wolters Kluwer Medknow Publications, and World Scientific (see Plastun et al., 2024a).

The position of most of the publishers can be summarized as “aggressive ignorance.” This means that they ignore the issue of stolen Ukrainian universities and occupied territories and are ready to provide misinformation on their official web-sites. In this way they play into the aggressor’s hand.

As a result, on official sites of publishers such as Springer, Taylor, and Francis, scientometric databases like Scopus/WoS, and academic social networks like ResearchGate or Academia.edu, there are thousands of publications where Ukrainian territories are marked as Russian, primarily because stolen Ukrainian universities in authors’ affiliations are called “Russian.”

Issue #2. International ISSN Centre and legalization of stolen Ukrainian journals

The ISSN, an international organization responsible for registering academic journals, has decided not to adhere to ISO 3166 (the UN country code standard) and to index Russian journals published in occupied Ukrainian territories (Crimea, Donetsk, and Luhansk regions). No compliance measures were implemented and no sanctions imposed against these journals for spreading propaganda.

As a result, stolen Ukrainian journals are present in the international academic sphere (by “stolen Ukrainian journals” we refer to academic journals that were seized by Russia along with the universities which published them. This includes the unlawful appropriation of their archives, ISSN numbers, editorial boards, and other intellectual assets).

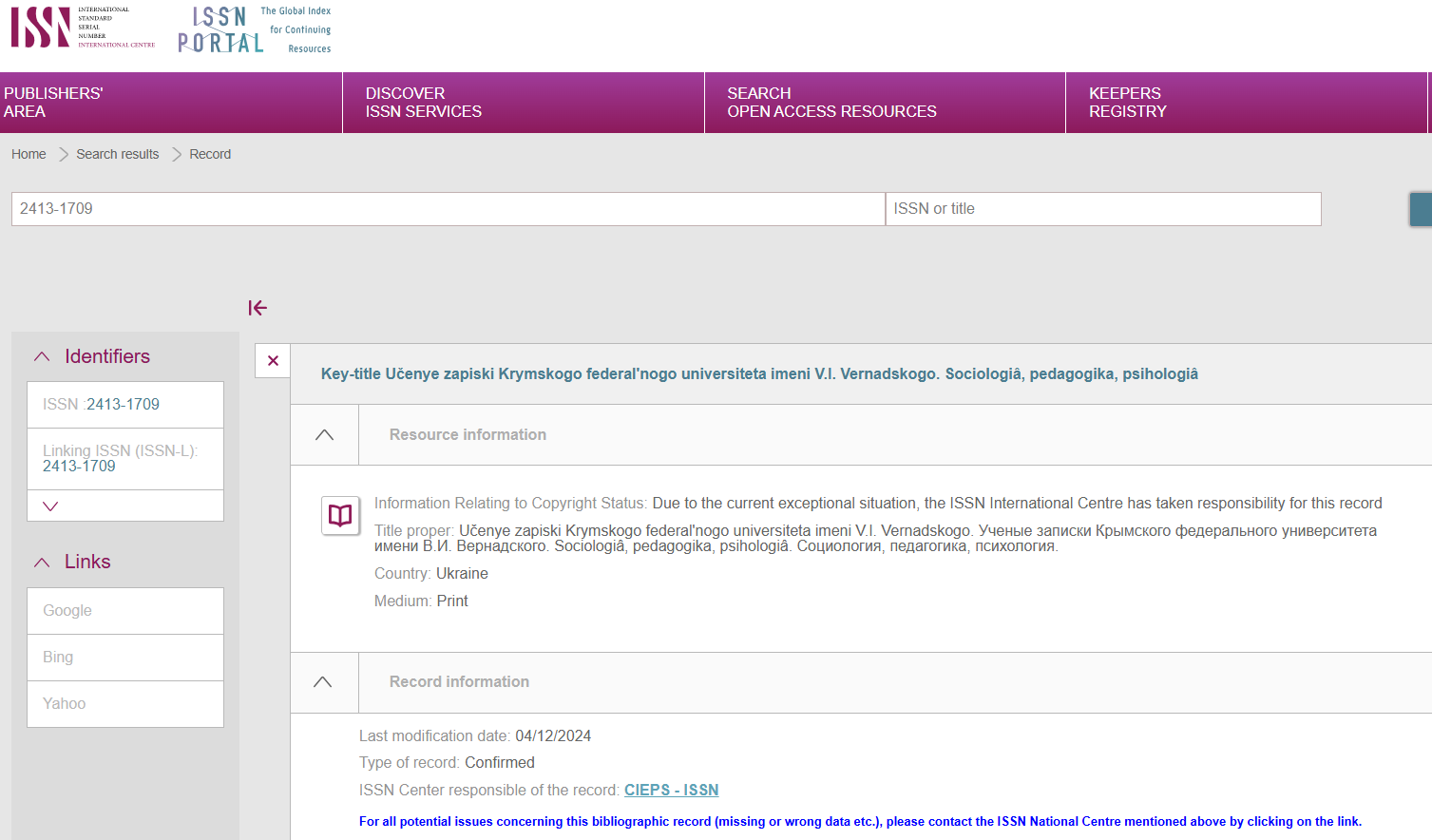

For example, Russia has stolen two Ukrainian journals: “Uchonyye zapiski Tavricheskogo natsionalnogo universiteta imeni V. I. Vernadskogo”: seriya “Filosofiya. Kulturologiya. Politologiya. Sotsiologiya” [“Scientific Notes of the Taurida National V.I. Vernadsky University”: Series “Philosophy. Cultural Studies. Political Science. Sociology”] (КВ No. 15718-4189Р dated September 28, 2009) and “Uchonyye zapiski Tavricheskogo natsionalnogo universiteta imeni V. I. Vernadskogo”: seriya “Problemy pedagogiki sredney i vysshey shkoly” [“Scientific Notes of the Taurida National V.I. Vernadsky University”: Series “Problems of Pedagogy of Secondary and Higher Schools”] (КВ No. 19680-9480Р dated January 25, 2013) and created in 2015 a new journal “Scientific Notes of V.I. Vernadsky Crimean Federal University. Sociology. Pedagogy. Psychology” (ПИ № ФС77-61813 from May 18, 2015). All the archives of these Ukrainian journals were stolen and today are present on the web-site of this new journal. In 2015, this journal somehow received ISSN number 2413-1709 (Figure 3).

Figure 3. A screenshot from the ISSN portal for the record 2413-1709

It is unclear how a stolen journal from an occupied territory received international registration. ISSN refused to comment on this issue.

Besides, ISSN confirmed the ISSN numbers of Ukrainian journals for years despite the fact that some of them were stolen and not controlled by their founders.

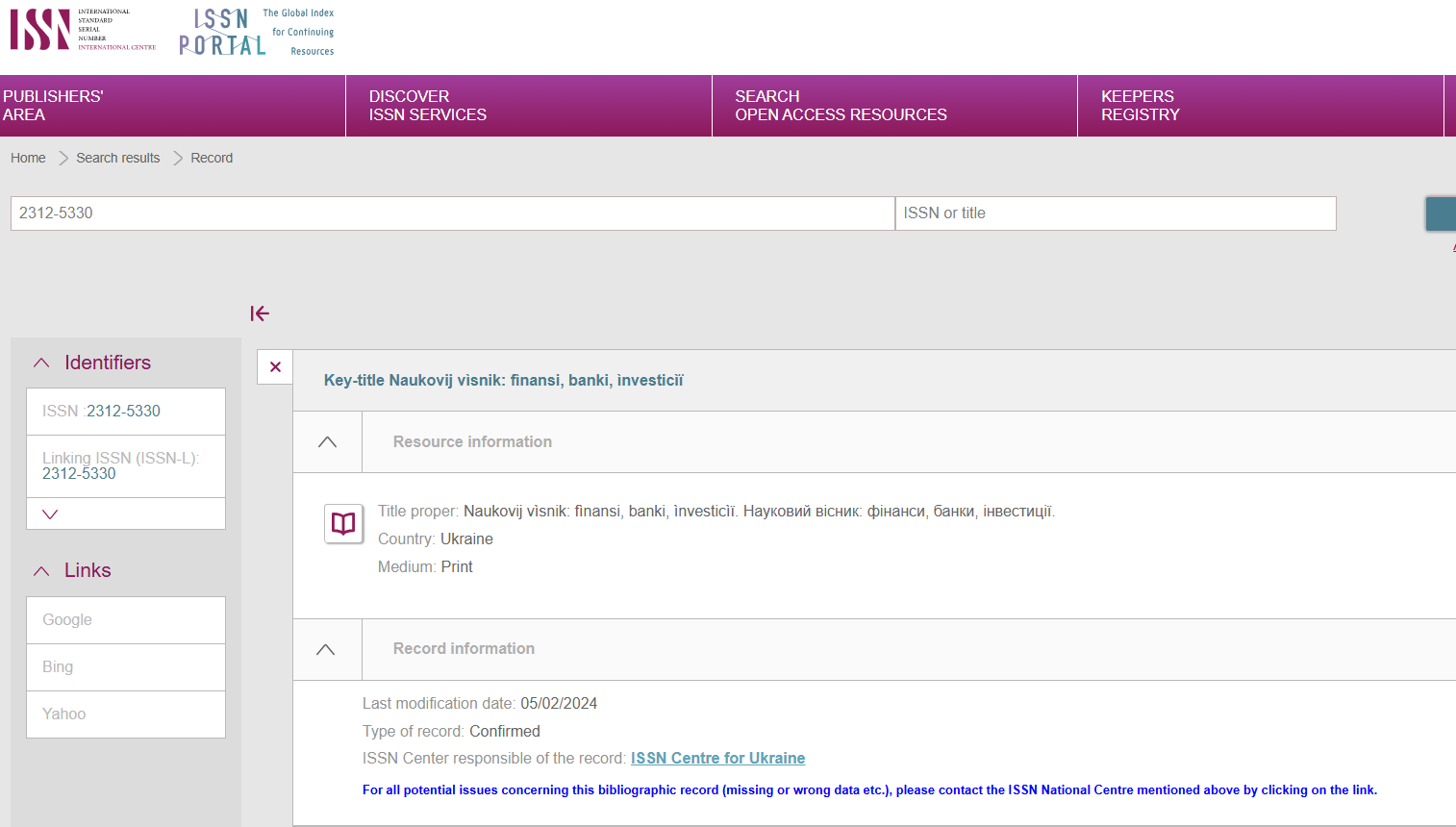

For example, Russia stole the journal “Naukovii vìsnyk: fìnansy, banky, ìnvestitsii” published by Vernadsky Crimean Federal University and renamed it into “Scientific Bulletin: finance, banking, investment” in 2015. Despite this, ISSN confirmed the number 2312-5330, which belongs to the Ukrainian journal “Naukovii vìsnyk: fìnansy, banky, ìnvestitsii” for ten years. This record is still active in 2025 (figure 4).

For more detailed examples visit this link.

Figure 4. A screenshot from the ISSN portal for the record 2312-5330

Stolen universities are used as an instrument of Russian propaganda in the following way (see Plastun et al., 2024a):

- they spread Russian propaganda narratives to support its aggression against Ukraine. Authors from the stolen universities publish academic papers that justify and support Russia’s aggression (Plastun et al., 2024, Plastun & Makarenko, 2024);

- stolen universities are actively involved in Russian efforts to assimilate the Ukrainian population on occupied territories: they use Russian textbooks in the educational process, they are involved in different events organized by Russia, in academic mobility within Russia etc.

Human Rights Watch (HRW, 2024) documented violations of international law by the Russian authorities related to the right for education in formerly occupied areas of Ukraine’s Kharkiv region and other regions that remain under Russian occupation.

Universities used as a tool to abduct and “reprogram” Ukrainian children

Russia extensively uses universities, schools, and even kindergartens to promote its propaganda. For example, new history textbooks justify Russia’s war on Ukraine and state that the goal of the “special military operation” (Russian euphemism for the war) is “the defense of Donbas and the preemptive provision of Russia’s security.”

In line with this, Russia has created a special “university exchange” program to recruit Ukrainian schoolchildren from the temporarily occupied territories. In 2024, about 3,700 children from the occupied Donetsk region were taken for tours and consultations on admission to Russian universities (Zelenetska, 2024).

Since 2022, Russians have deported more than 20,000 Ukrainian children for “re-education” under the “University Sessions” program, according to research by the Almeda Centre of Civil Education. “University Sessions” is one of the projects of educational programs used by Russia to form the so-called “Russian identity” in children from the temporarily occupied areas of Ukraine (Lychko et al., 2024).

Almeda Centre of Civil Education has identified 81 Russian universities where the so-called University Sessions were implemented. Among them are stolen Ukrainian universities, such as V.I. Vernadsky Crimean Federal University and Sevastopol State University.

In June 2022, the President of the Russian Union of Rectors, Rector of Moscow University V.A. Sadovnichy spoke at the opening of the First Forum of Educational Organizations of Russia, “Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics.” The goal of the forum was facilitation of rapid integration of universities of the “Donetsk People’s Republic” and “Luhansk People’s Republic” (i.e. occupied territories of Ukrainian Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts) into the educational space of the Russian Federation.

He said: “This year we accepted 115 [applicants] – these are the children of those who participated in the military actions, and those who participated [in the war] themselves. Another hundred, or even several [hundreds], we transfer from other universities, if they ask, from universities in new territories or other universities, we also transfer them, despite the lack of places.” (note: “new territories” is the Russian euphemism for occupied Ukrainian land – ed.).

As another example, in autumn 2023, students of grades 9–11 from different regions of the Russian Federation, “including the Luhansk and Donetsk People’s Republics, Zaporizhzhia and Kherson regions, the Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol” (i.e. occupied Ukrainian territories) attended the the Winter School on Financial Security organized by Institute of Physics named after P.N. Lebedev of the Russian Academy of Sciences (also a sanctioned entity).

Conclusions and recommendations

The most obvious form of responsibility for such actions can be sanctions against Russian institutions that have participated in the theft or illegal use of resources of the stolen universities; against those academic journals that were stolen from Ukrainian universities, and against those international organizations/institutions that collaborate with Russian clones of the stolen Ukrainian universities and academic journals.

Despite more than 22,000 different sanctions against Russia, the academic sphere is still relatively untouched. Key arguments against sanctions are as follows: science is outside of politics; sanctions might disrupt a free flow of thoughts and might punish innocents; Russian science is an essential element of global science, and sanctions might hurt worldwide science and human development; overall, sanctions are costly and inefficient.

Chumachenko et al. (2022) show that neutrality is inappropriate in this situation. Russia’s unjustified military invasion of Ukraine is unprecedented; it requires unprecedented reactions from the world scientific community. A proper discussion is needed to change the existing consensus: if there is a crime, there should be punishment. It’s not about politics; it’s about justice.

However, sanctions are not the only option on the table.

Plastun et al. (2024a) argue that academic journals, publishers, and scientometric databases should monitor materials published on their websites to prevent publication, indexing, and display of Russian propaganda related to its appropriation of Ukrainian territories.

Plastun and Makarenko (2024) believe that a sharp increase in reputational risks for international organizations (publishers, scientometric databases, etc.) caused by higher attention to these issues within the academic community and media can incentivise publishers to reconsider their cooperation with Russian academic institutions and journals. This will prevent using science as a tool of propaganda.

The first steps to fix the problem are as follows:

- Ukraine’s Ministry of Education and Science should publish the list of stolen Ukrainian universities and academic journals as well as Russian universities created with assets of stolen Ukrainian institutions;

- Publishers/database owners should stop mentioning stolen universities in affiliations since they officially do not exist.

- Publishers/database owners should stop marking Ukrainian territories as Russian (in fact, they need to start adhering to the UN standard). If the authors insist on publishing with the wrong affiliations, their articles should be rejected as war propaganda.

- The International ISSN Center should cancel the registration of stolen Ukrainian journals and media.

- The Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) should issue guidance for journals/publishers on no collaboration with stolen Ukrainian Universities/Facilities/Journals.

An example of a responsible position is actions of the international publisher Brill regarding the Russian journal “Scrinium”. Right after the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Brill contacted the chief editor of “Scrinium” directly to clarify his position regarding the war and its relationship with the Russian Academy of Sciences. After ensuring compliance (he was not affiliated with RAN and signed an anti-war letter), Brill decided to continue publishing “Scrinium.” Additionally, Brill ensures that it does not accept funding from the Russian Federation.

Ukrainian authorities should take a more active position and initiate discussions with leading international publishers (Springer, Elsevier, Taylor and Francis, MDPI, etc.), database owners (Clarivate, Elsevier), and related organizations (COPE, International ISSN Center, and others) regarding these issues.

References

- Chumachenko, D., Bilous, O., Sherengovsky, D., & Zarembo, K. (2022). Russian universities must suffer tougher sanctions. Times Higher Education.

- Hague Convention (IV). (1907). Respecting the laws and customs of war on land and its annex: Regulations concerning the laws and customs of war on land. Retrieved from

- HRW. (2024). Ukraine: Forced Russified Education Under Occupation.

- Kubijovyč, V., Miller, M., Ohloblyn, O., Stebelsky, I., & Zhukovsky, A. (2022). Crimea.

- Lychko, T., Vorobyova, A., Sulialina, M., Shapoval, O., & Okhredko, O. (2024). The “University sessions” program as the instrument for the indoctrination and destruction of the Ukrainian identity of children and youth from the temporarily occupied territories (Analytical report) (78 p.). Kyiv: CCE “Almenda”.

- MESI. (2023). Overview of the current state of education and science in Ukraine under russian aggression.

- Plastun, A., & Makarenko, I. (2024). International Academic Collaboration with Russian War Supporters (16 p.). Sumy State University.

- Plastun, O., Makarenko, I., & Berger-Hrynova, T. (2024a). Science vs Propaganda: The case of Russia (15 p.). Sumy State University: CNRS.

- Redzik, A. (2004). Polish Universities During the Second World War.

- Scopus. (2024). Russian Academy of Sciences.

- UNESCO. (1945). Education under enemy occupation in Belgium, China, Czechoslovakia, France, Greece, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Poland (Bulletin No. 3).

- UNESCO. (2024). Analysis of war damage to the Ukrainian science sector and its consequences.

- Zelenetska, V. (2024). The occupiers have created a program for Ukrainian children to study in russia.

Photo: depositphotos.com/ua/

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations