Reconstruction, green transition and EU integration are interdependent vectors for a Green Recovery. Ukraine has been getting closer to EU membership as accession negotiations are likely to open this year. Integration into the EU internal market together with a dynamic post-war reconstruction may lead to a substantial restructuring of the national economy, which will impact the energy demand and emissions of greenhouse gases (GHGs) in Ukraine. Despite all the uncertainties amidst the full-scale Russian invasion, the projections of the potential structural changes in Ukraine’s economy and their energy and climate implications are needed to underpin future-proof policymaking and investments.

In this article we outline key macroeconomic developments and structural shifts in Poland and Romania during their EU integration. EU accession of these countries not only led to a higher-growth pathway, but markedly changed production, consumption and trade patterns. This result is highly relevant for Ukraine. Comparable population size and similar socialist legacy make these countries good examples of possible structural shifts that Ukraine might experience during its EU accession. While Ukraine will follow its own path, studying some stylised facts from Poland and Romania may help align expectations and pave the way to robust policymaking to ensure the efficiency of the post-war recovery and EU accession process.

Ukraine’s EU future and importance of regional peers’ experience

Ukraine’s integration to the EU is the focal point for the modernization of the country. It will help attract the critically needed investment to Ukraine’s economy. Being an EU candidate and losing the previously significant markets in the CIS following the Russian invasion, Ukraine has little choice but to find its own niches and comparative advantages in the EU market. Integration into EU value chains will also provide an important political anchor for the country.

EU integration is supported by the vast majority of Ukrainians who see their future among the other 27 EU nations. However, the integration process will require a significant effort from Ukraine, since preserving the pre-war structure of the economy will not allow Ukraine to become an efficient part of EU value chains.

Our analysis of Poland and Romania shows that policy steps and institutional changes towards macroeconomic stabilization followed by stimulation of structural shifts in the economy and support to new consumer habits were among the key factors of success in achieving stable economic growth decoupled from GHG emissions.

We identified 10 key macroeconomic parameters that should be considered during Ukraine’s after-war recovery and EU integration. These parameters support three key findings of our research, so in the following text we advise a reader to consider findings as headings and parameters as sub-headings.

Finding I: Early stabilization led to rising productivity

Macroeconomic stabilization that preceded the EU accession of post-socialist economies created the fundamental precondition for future improvement of production factors, capital inflow and eventually overall productivity of the economy. This was the result of consistent policy reforms, institutional changes and political will for effective transformation of the economy demonstrated by these countries before they became EU Member States. Establishing the preconditions for massive privatization, effective protection of ownership and market-based functioning of the key sectors were especially important for the further transformation and modernization of the states.

While having some positive shifts before the Russian full-scale invasion, Ukraine did not manage to achieve a progress comparable to the pre-accession situation of Poland and Romania. Consistent policy reforms in Ukraine can provide another chance to efficiently transform the economy.

Economic stabilization is one of the Copenhagen criteria that countries must comply with on their EU accession path. This typically required a combination of steps to ensure budget discipline, efficient privatization, market opening, and predictable monetary and fiscal policies. The accession process anchors expectations of future growth, frontloading some of the benefits of politically difficult reforms in the form of early capital inflows and macroeconomic stabilization.

Parameter 1: Stabilization

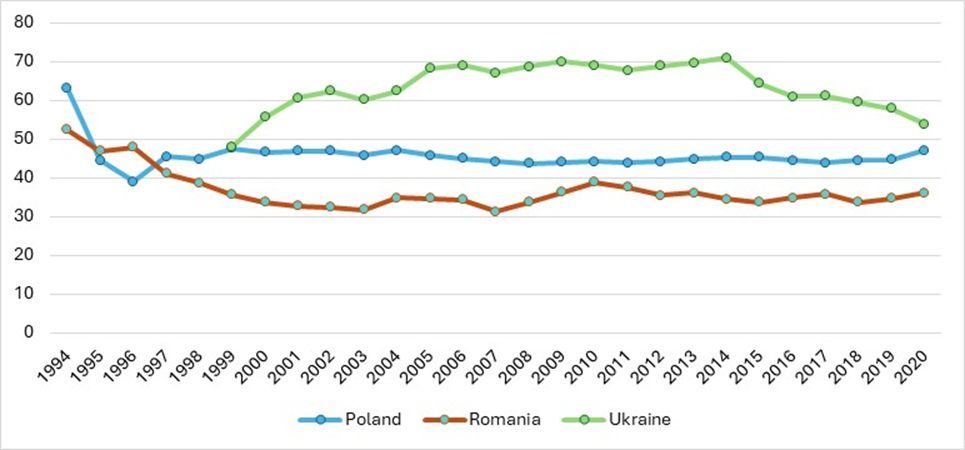

Transition in Poland and Romania began with a substantial reduction of the role of the state in the economy – cutting subsidies to enterprises, quick privatization (see Figure 1). Active economic liberalization in both Poland and Romania allowed much lower pressure on the state budget, limiting subsidies tol below 50% of the total expenses. On the contrary, Ukraine kept soft budget constraints for state-owned enterprises until 2014. The level of subsidization of the economy is likely to change significantly in the first years post-war due to the destruction of many industrial assets and infrastructure. But eventually the role of the state in the economy has to fall to unleash the efficiency gains needed to be competitive in the EU market.

Figure 1. Subsidies and other transfers, % of the total expenses

Source: World Bank

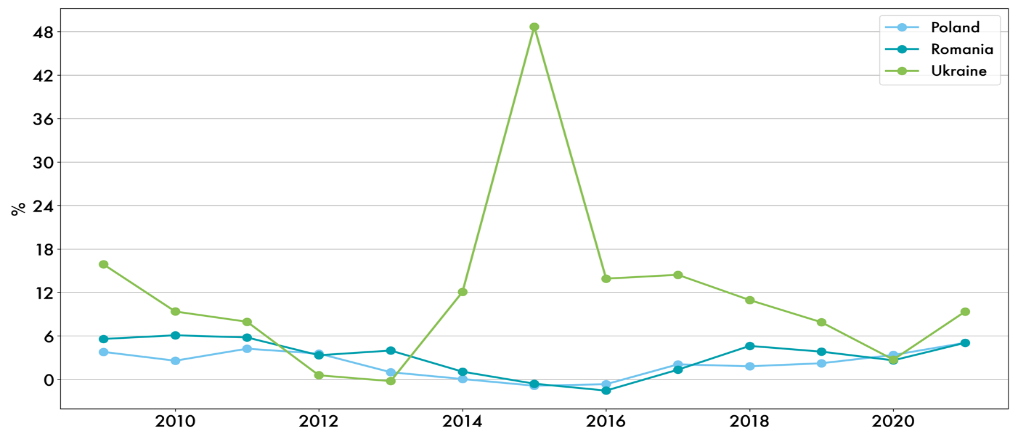

Stabilizing the inflation rate and reaching a predictable trend as the result of inflation targeting by the central bank is another clear trace of the EU integration-inspired policies applied in the transitional countries. Ukraine started following a similar trend only in 2015: it introduced inflation targeting which led to the reduction of the inflation rate. However, various other factors — high exposure to external fluctuations, high volatility and low development of financial markets, and the war — together resulted in higher inflation in Ukraine.

Figure 2. Inflation rate, %

Source: World Bank

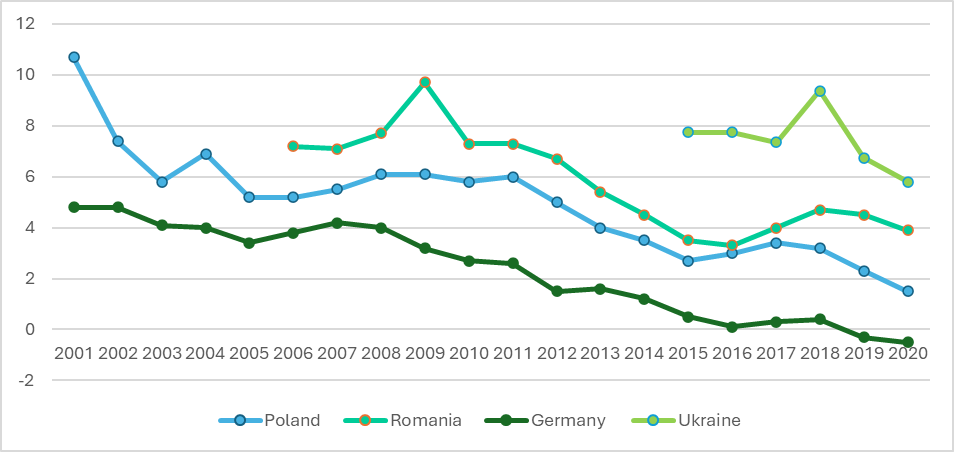

Parameter 2: Better access to capital

Improvement of the national credit ranking as a result of macroeconomic stabilization substantially lowered capital cost in Poland and Romania. While government bond yields in these countries remain higher than in Germany, they are 60% lower than yields paid by Ukraine before the full-scale Russian invasion. The decline in public borrowing cost was largely mirrored in private borrowing cost.

Lower capital cost contributes substantially to reshaping economic structures. In the energy sector, for example, lower capital cost favour investments in renewables, nuclear and energy efficiency over using fossil fuels.

Figure 3. Interest rate on the ten-year government bonds

Source: OECD and World Government Bonds

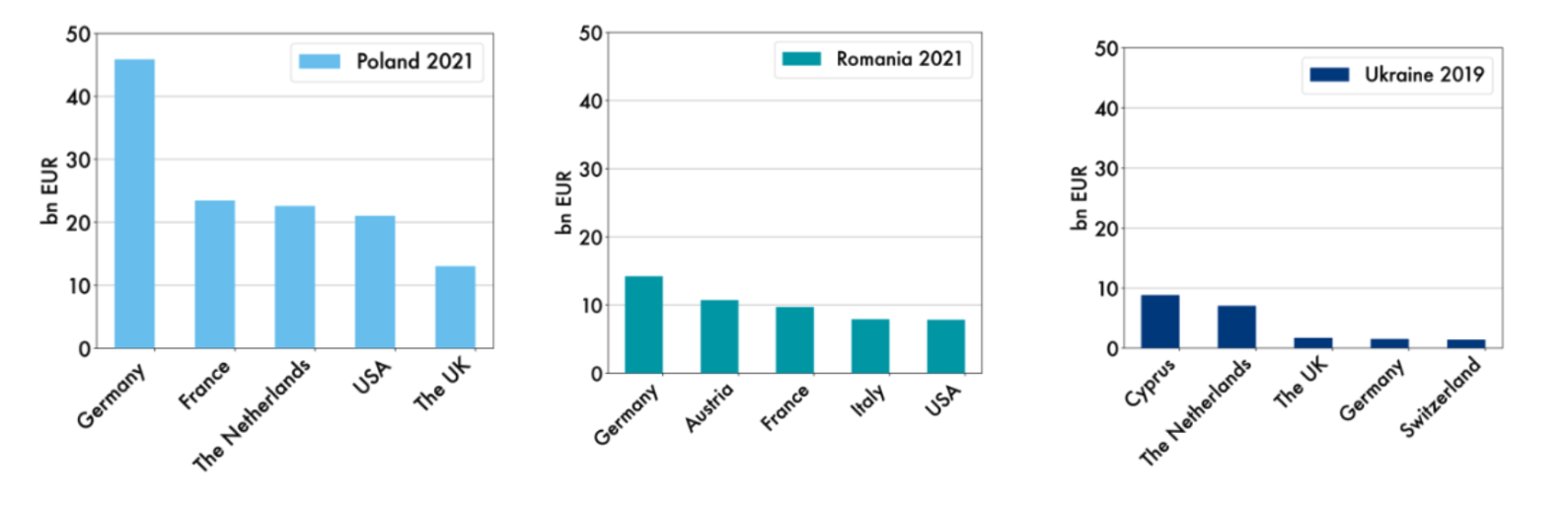

Parameter 3: Increasing foreign direct investment inflow from the EU

Macroeconomic stabilization and creating conditions for capital inflow (including effective protection of ownership rights, transparent markets functioning and privatization rules) went hand-in-hand with increasing foreign direct investments in Poland and Romania. In contrast to Ukraine, which saw a short-lived surge of inflows in 2005-2008, FDI flows to Poland and Romania recovered quickly after the financial crisis.

FDI to Poland and Romania was “not just money”. Investors from successful EU economies brought substantial productivity improvements, while a large share of FDI into Ukraine was round-tripping of domestic funds through offshore locations such as Cyprus or the Netherlands (figure 4).

So far, the Ukrainian energy sector has seen very little foreign investment. In Poland and Romania the picture is mixed – legacy power generation remained state-owned, while foreign investments in renewables are on the rise. Romania has higher foreign investments in gas extraction and electricity distribution since energy-sector FDI is strongly dependent on the national market regulation.

Figure 4. Origin of FDI: Poland, Romania and Ukraine

Parameter 4: Increasing labour productivity

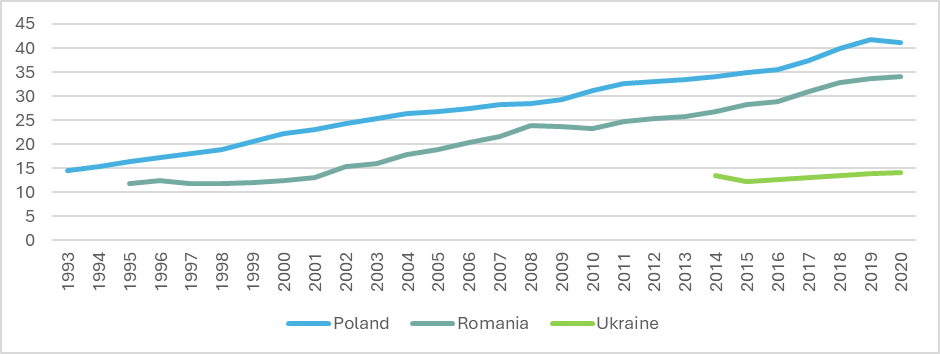

Rising labour productivity (measured as the amount of GDP produced per hour worked) clearly indicates the efficiency gains that stabilization and capital inflow can bring to the transition economies. Poland and Romania have seen a tremendous increase in the labour productivity leaving Ukraine visibly behind. The increase in labour productivity can be expected as the result of comprehensive structural reforms and correct policies in the Ukrainian economy, supported by FDI inflow and development of high-tech industries.

Figure 5. Labour productivity (USD of GDP per hour worked)

Source: OECD and own calculations based on Pension Fund of Ukraine and World Bank

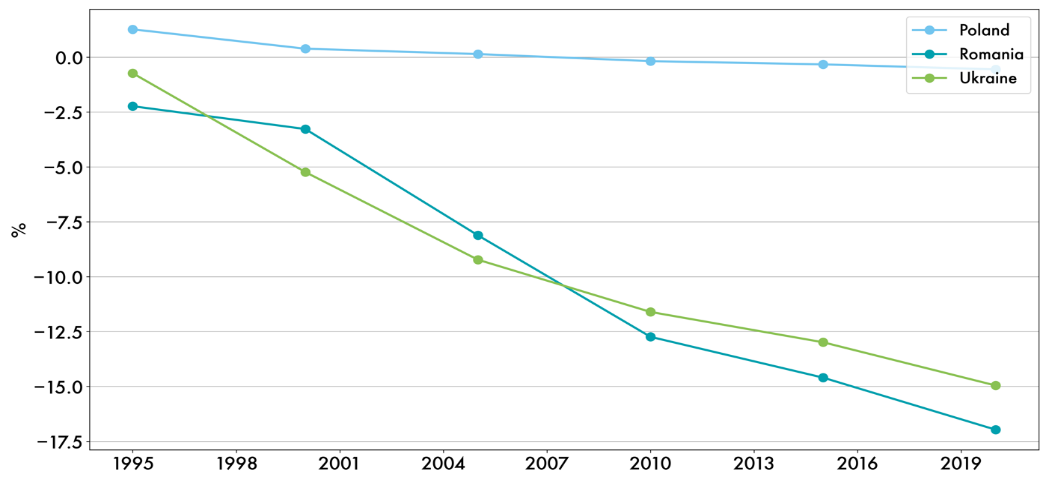

Note that a significant emigration and other population outflows creates a big challenge for productivity increase of transition economies. This problem will probably be extremely difficult for post-war Ukraine. However, the example of Romania which suffered from massive population outflow too suggests that an efficient transformation of the economy and increasing investment can decouple the population outflow from labour productivity increase.

Figure 6 Deviation from 1990 population level, %

Source: Own calculations based on the UN data

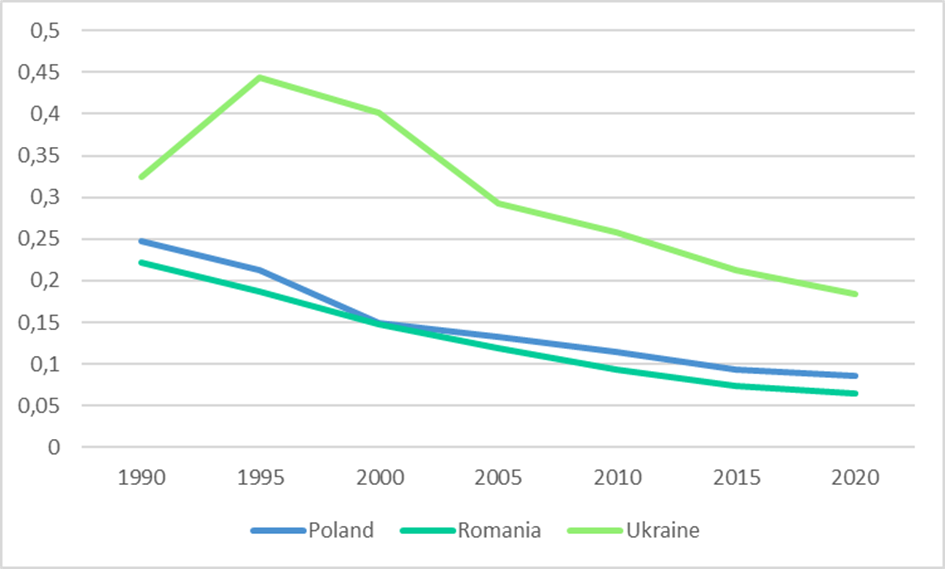

Parameter 5: Increasing industrial productivity

A visible improvement in industry’s energy efficiency (measured by lower amount of energy per unit of value added) is another outcome of the efficient transition in Poland and Romania compared to Ukraine. A significantly higher energy intensity of Ukraine’s GDP since the 1990s (figure 7) demonstrates that the country has implemented an insufficient amount of energy efficient technologies to bring its energy intensity closer to the EU levels.

Lowering the energy intensity of GDP has a direct impact on lowering the GHG emissions and thus achieving climate goals.

Figure 7 Energy intensity of GDP

Source: Enerdata

Finding II: Integration to EU market results in a significant restructuring of the economy

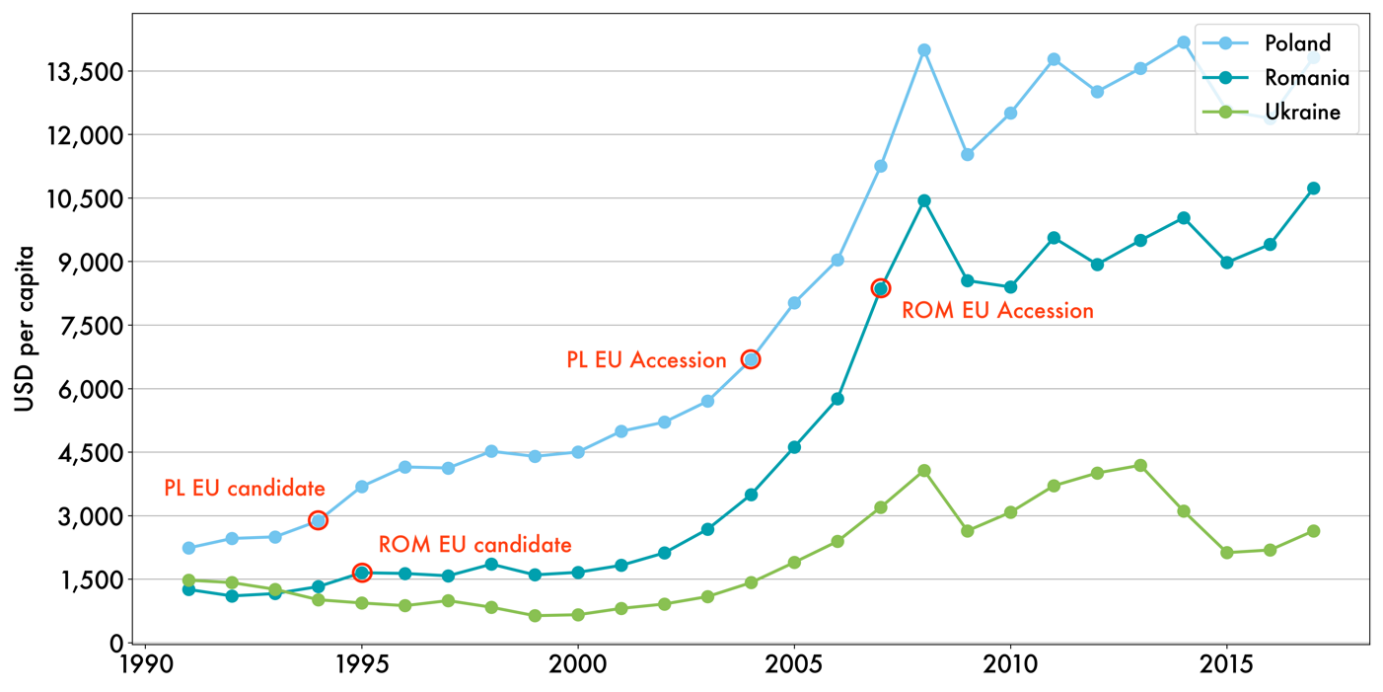

The economic growth path in Poland and Romania coincides with the steps taken by these countries in integration to the EU – starting from early stabilization and modernization of the economies. Romania’s economic growth had a lower pace compared to Poland at the early stage but eventually reached a similar level after a decade of EU integration. A similar outcome can be expected for Ukraine in case of successful reforms and EU integration.

Сhanges in the structure of the economy are another outcome of EU integration of the transition countries. Shifts in demand lead to a decline in some traditional sectors of the economy and local producers finding new comparative advantages.

With integration to the EU market transition economies managed to find their new niches, which is visible in the new export structures. The decline in the traditional industries was followed by integration of the new technologies and growth in manufacturing and services, also leading to lower emissions.

A different tendency was observed in Ukraine before 2022, where a shift towards less technologically advanced industries took place and GHG emission reduction was related mostly to deindustrialization rather than technological advancement.

Creation of a stable environment for FDI inflow and relevant policy steps to stimulate new high-tech industries would allow Ukraine to achieve the outcome similar to successful transition economies.

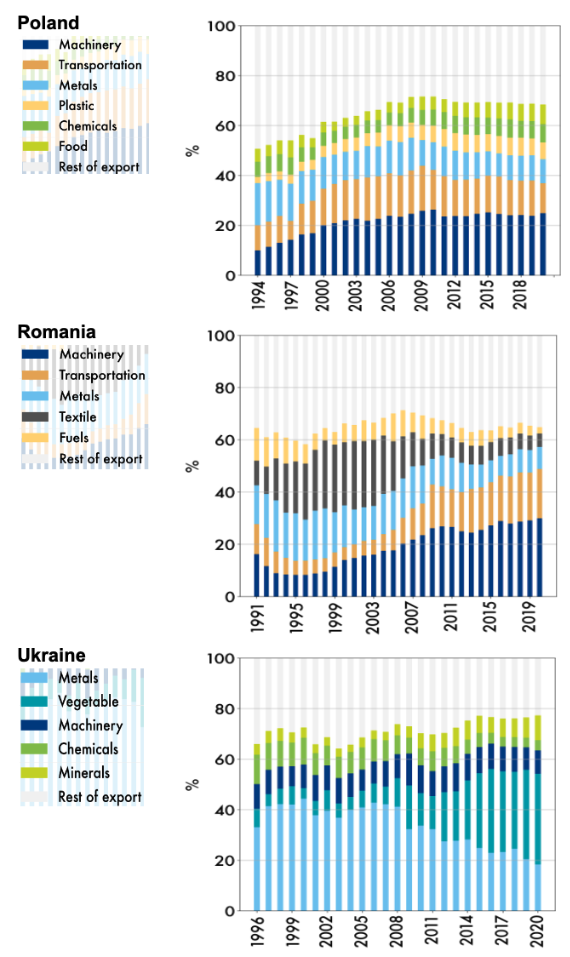

Parameter 6: Increase in technologically advanced exports

Structural adjustment of the economy is visible in the export structure. EU integration resulted in an increase of the share of machinery and services (mainly transportation) in the structure of Polish and Romanian exports (figure 8). Shares of traditional industries like textile, metals or agriculture significantly decreased since the 1990s.

In Ukraine, the situation is different: the share of metals has been constantly declining, while the share of agricultural goods has increased. This tendency signals the general deindustrialization of the economy, even though the share of services in the general structure of Ukraine’s economy increased similarly to Poland and Romania.

Figure 8. Share of the main export sectors (in %)

Source: World Bank

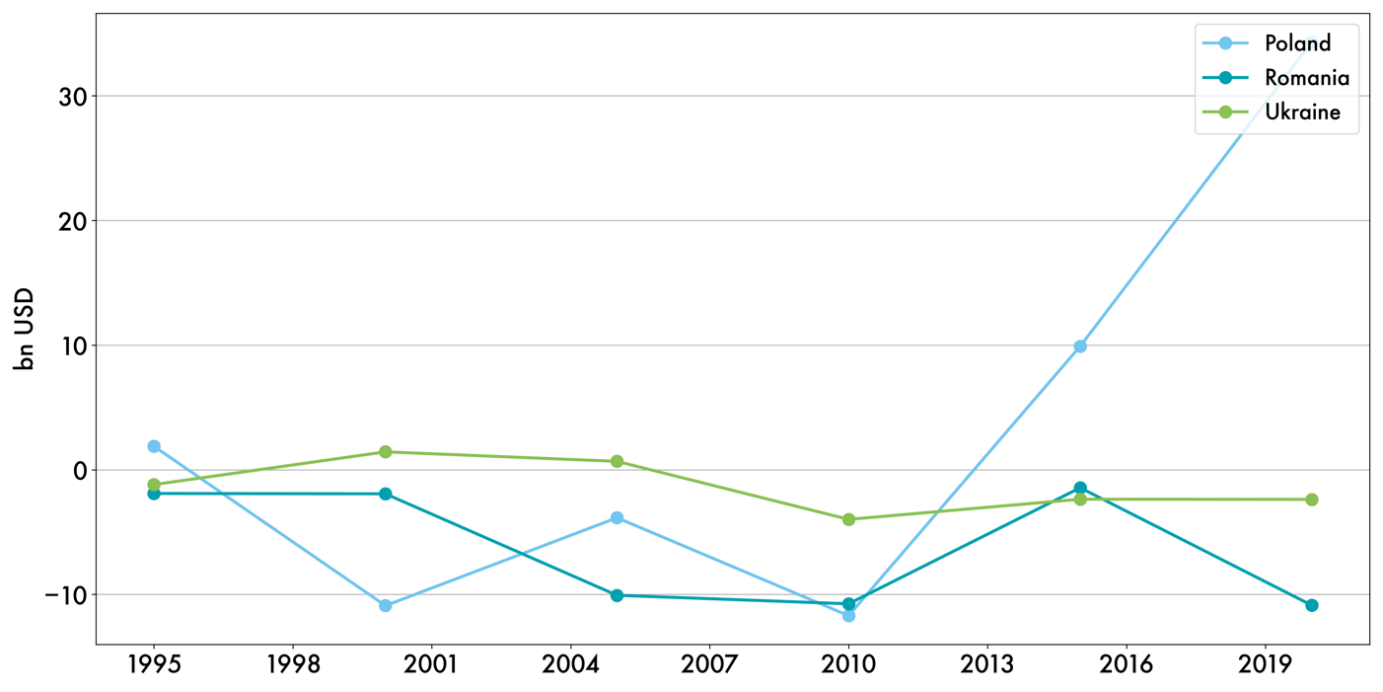

Parameter 7: Export growth tends to lag behind the increase in imports of goods & services

Usually imports of transition economies grow faster than exports resulting in a negative trade balance (figure 9). If capital inflows (e.g. FDIs, remittances) does not cover this deficit, this may result in devaluation of national currencies.

This is economically sensible, as long as future growth allows to pay back the accumulated deficits. The case of Poland actually shows how growing exports can eventually outweigh imports.

Figure 9. Net trade in goods and services (bn USD)

Source: World Bank

Finding III: Transformation of the economy leads to new consumer habits

Economic growth associated with economic reform and integration to the EU market ultimately results in improvement of people’s living standards, growing personal income and demand for a wider range of goods.

This tendency may have a twofold impact on the environment: on the one hand, people get additional opportunities for personal-level investment into energy efficiency. On the other hand, a higher demand for energy consuming appliances, e.g., personal vehicles or larger apartments, can also be observed. The negative climate impact of the latter can be mitigated by prudent policy steps in certain sectors, such as development of public transportation.

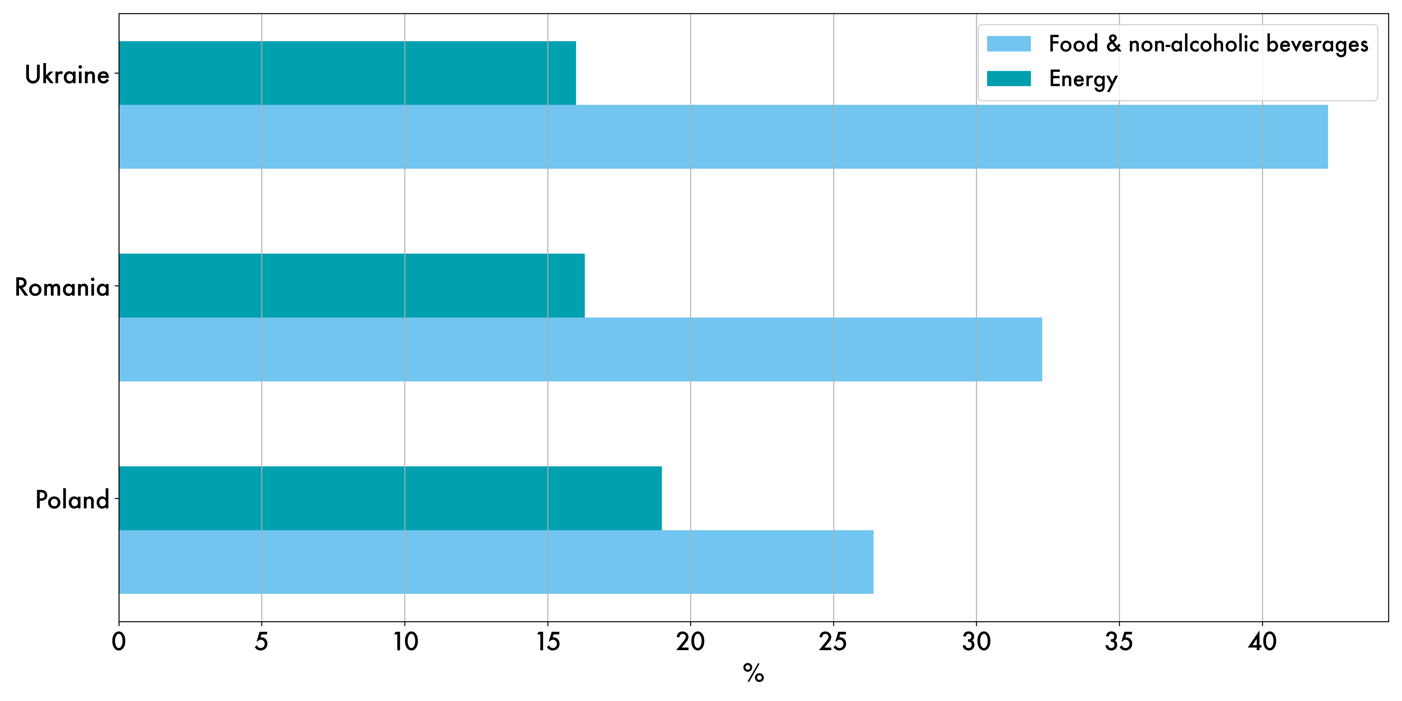

Parameter 8: Decrease of the share of basic needs in personal expenditure

Comparing the structure of household expenditures, we see that people in Poland and Romania spend much lower share of their income on food than Ukraine and a similar share on energy.

Usually richer people spend a lower share of their incomes on food. Thus, as Ukraine approaches the EU, we expect the shares of spending on food and energy in Ukraine to resemble those in Poland and Romania, especially when the government allows market-based tariff setting. This will incentivize Ukrainians to save energy.

Figure 10. Share of household expenses (2021)

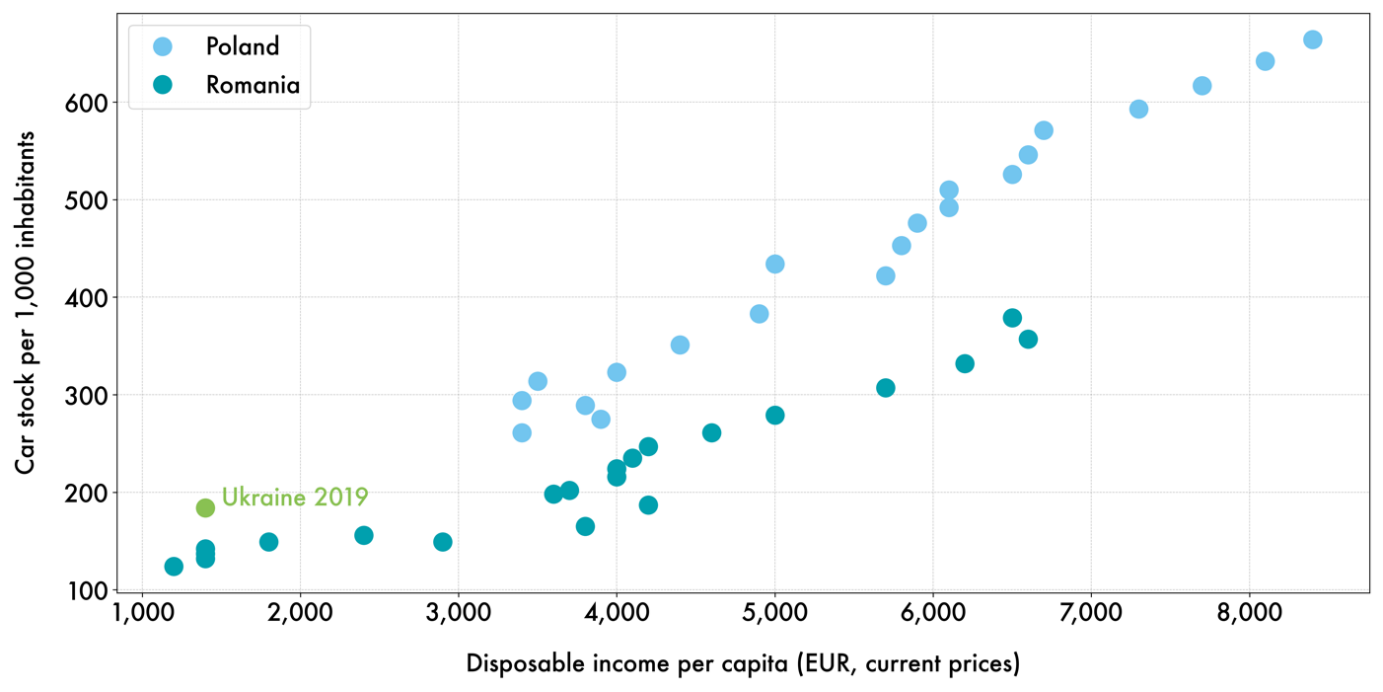

Parameter 9: Personal car ownership significantly increases with increasing income

Improvement of living standards is likely to stimulate demand for private vehicles. The examples of Poland and Romania demonstrate a significant increase of car ownership when disposable income per capita exceeds EUR 4000 per year. Government steering – e.g., through encouraging clean transportation alternatives – might be needed to mitigate the negative impact of this tendency.

Poland and Romania experienced rapid GDP growth in the early stage of the accession process. Growth subsequently stabilized at a relatively high pace, recovering quickly from temporal shocks. The case of Ukraine shows how failure to achieve early stabilization, later restructuring of the economy and integration to the EU market has led to falling behind the tendencies of regional peers.

Figure 11. Car stock per 1,000 inhabitants vs average income

Source: Own calculation based on Eurostat and Helgi Library

Parameter 10: A stable and resilient economic growth

Comparing the entire transition path of the three countries, one can clearly see that Ukraine lost pace already in the mid-1990s and was not able to reach the GDP levels of Poland and Romania in the following years. A much bigger impact of the external economic shocks (including the global financial crisis of 2008-2009), has been another important feature of the Ukrainian economy since 1991. However, an active recovery, reforms, and integration to the EU market can stop this decoupling from regional peers in the future bringing Ukraine to a fast and sustainable economic growth.

Figure 12. Nominal GDP per capita (USD)

Source: World Bank

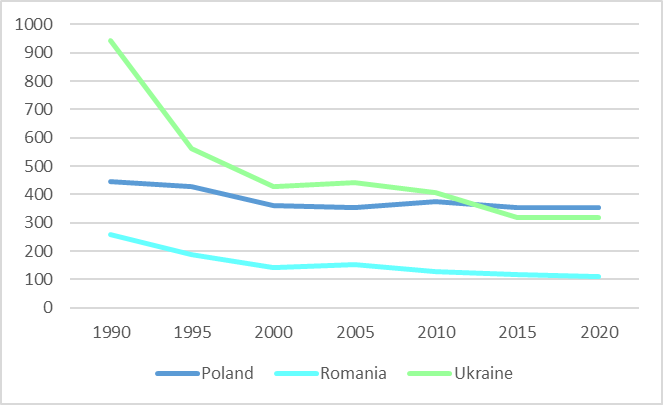

All the three countries under consideration have seen a significant drop in GHG emissions (figure 13) due to structural changes in the economy. In Ukraine, due to rapid economic restructuring, GHG emissions rate had fallen by more than 2.5 times between 1990 and 2000, while the emissions reduction in Poland and Romania constituted around 20% and 55% respectively.

The comparison to GDP shifts in the three countries demonstrates a tendency to decouple economic growth from GHG emissions. Poland and Romania managed to achieve remarkable growth keeping the GHG emissions at a stable level post 1990s.

Figure 13. GHG emissions rate in Poland, Romania and Ukraine, excluding LULUCF (mn tonnes of CO2 eq.)

Source: UNFCCC

Conclusion

Integration of Poland and Romania into the EU triggered an “economic miracle” in both countries. A virtuous cycle of profound reforms, stabilization, foreign investments, productivity gains and structural change unleashed enormous growth potential, drastically improving living standards.

The relevant productivity gains and sectoral shifts substantially reduced the energy intensity of GDP and enabled substantial reductions in emissions. The associated increase in personal incomes of the population results in changing consumer habits that can improve personal energy efficiency if supported by relevant policies.

However, it is important to realize that the tremendous success of these two countries on their path to economic transformation was a result of not only the general driving forces associated with the integration to the EU internal market, but also the pre-accession steps and clear political will for a transition at the national level.

We believe that the strong motivation of Ukraine to proceed with the structural economic reforms on its path to EU accession will also result in deep shifts leading to the improved economic performance and significantly lower GHG emissions rate similar to the cases outlined.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations