At this time, the government is developing the tax reform (again) but is either lacking the general view on the main direction of changes or not communicating its view. This article suggests that Ukrainian tax system should be at least marginally better than in the neighbouring countries in order to attract both foreign and domestic investment.

In summer 2015 the government intends to adopt the “true” tax reform that should be enacted since January 1st 2016 and is intended to correct the drawbacks of the “preliminary” tax reform adopted on December 28th 2014, with which business is quite unhappy. Hence, there are just about three months left for development of the Tax Code changes. Yet, the web-page of the working group responsible for the reform is practically empty – it contains only the provisions from the Coalition Agreement and Government Program that are either already adopted or too general. There is, however, a discussion of the future tax reform in the media (e.g. here and here).

Since there is no ideal tax system, which tax system would be good for Ukraine? My suggested answer is – anything better than those in the neighbouring countries. Remember an old joke – two hares are running away from a wolf, and one says to another: “You cannot run faster than a wolf anyway.” – “I don’t need to run faster than the wolf, I just need to run faster than you do”.

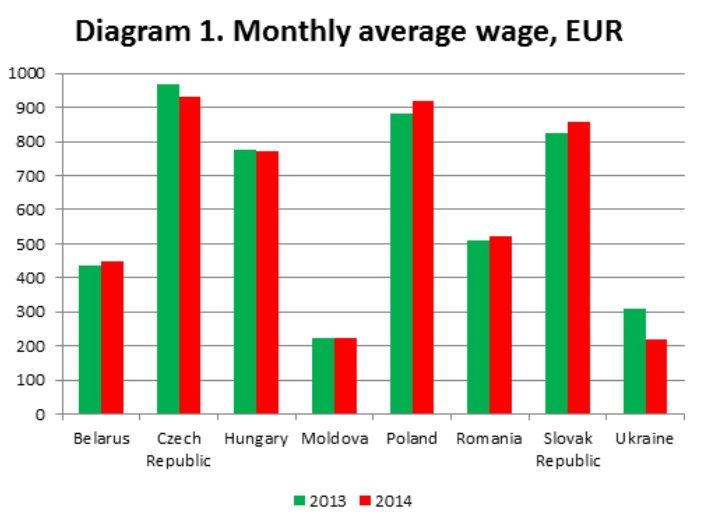

Now, as capital is leaving Russia, a natural question arises – why not to attract this capital to Ukraine? Having asked this, the next question is – why would investors want to come to Ukraine, what is the competitive advantage of Ukraine over the neighboring countries? An immediate answer is – wages (Diagram 1). Ukrainian labour is no less skilled than Polish or Romanian, and yet it is 2-3 times cheaper.

Data source: country statistical agencies

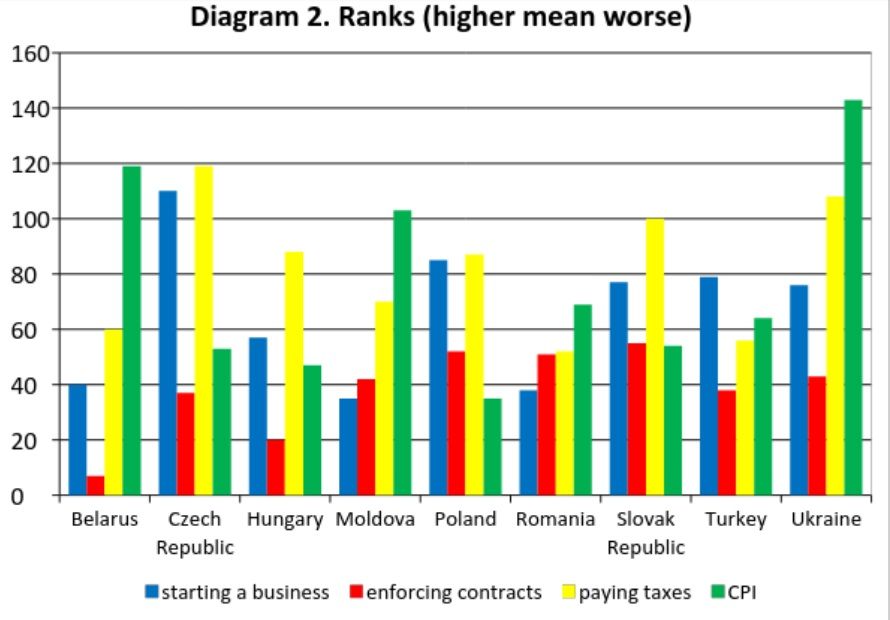

However, cheap labour alone is not enough to attract investment. As much, or even more, important is the regulatory environment. Diagram 2 shows how Ukraine compares to its neighbours with respect to a few of Doing Business indicators. We see that by “starting a business”, “enforcing contracts” and “paying taxes” Ukraine is comparable to other Eastern European states and Turkey, while Corruption Perception Index (CPI) is much higher. I would say that the taxation system is responsible for a substantial share of this index value.

Data source: Worldbank Doing Business-2015 report, Transparency International Corruption Perception Index-2014

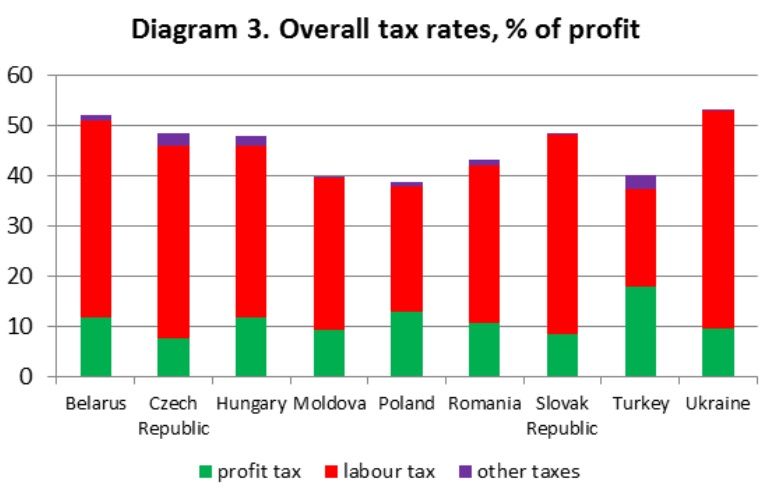

Let’s look at the taxation system. Diagram 3 shows that with respect to profit tax Ukraine is in line with other countries, but labour taxes (personal income tax and social contribution) are among the highest in the group. Of course, the problem with social contributions and “salaries in envelopes” is widely known. Diagram 3 demonstrates that without addressing this problem, Ukraine will be at a disadvantage compared to the neighbouring countries, and should not expect to attract many foreign investors who pay “white” salaries and thus are in an inferior position compared to domestic companies that use “grey” payment schemes.

Data source: Worldbank Doing Business-2015 report

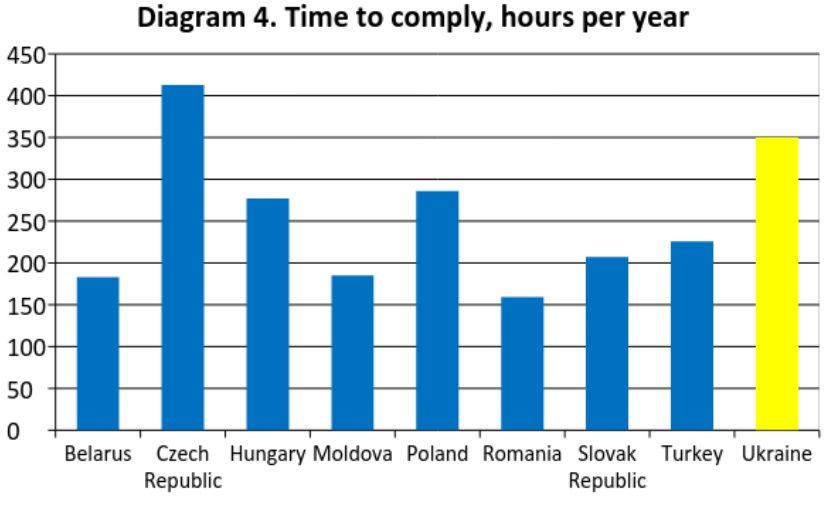

Diagram 4 clearly shows another big disadvantage of the Ukrainian tax system as compared to our neighbours. Specifically, Ukraine has the second highest cost of compliance, at 350 hours per year (assuming eight-hour working day, that’s two months of full-time work!).

Data source: Worldbank Doing Business-2015 report

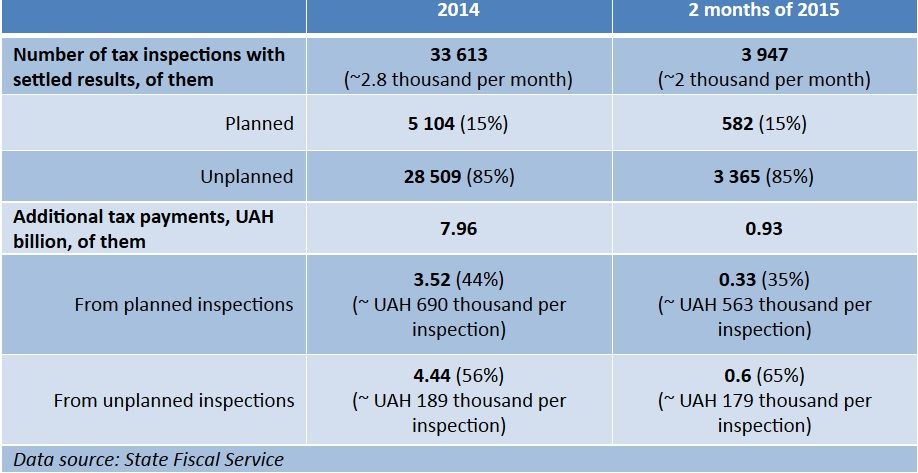

Finally, the next table shows one aspect of compliance that is perhaps among the worst for business – tax inspections. Since June 2014, the State Fiscal Service provides the data on the number of tax inspections and the sums of additional tax payments arising from those inspections. While looking at this table, keep in mind that small enterprises (with annual revenues lower than UAH 20 million) enjoy the moratorium on inspections. The latest available data on the size distribution of enterprises are from 2013. At that time, about 5% of enterprises exceeded the 20-million threshold (then equal to EUR 2 million). Assuming that the size distribution of firms is rather stable, at the end of 2014 there were about 30 thousand of “not small” enterprises that could be inspected. Hence, on average each of such firms can expect at least one inspection per year. The additional amounts of taxes due as a result of inspections are also quite substantial.

The analysis above suggests the following directions for the tax reform:

The analysis above suggests the following directions for the tax reform:

- Reduce labour taxes and at least slightly reduce the overall enterprise taxation level. Reduced revenues can be replenished with taxes on consumption.

- Reduce compliance cost by making it more profitable to comply than to evade. The necessary condition for this is making the Tax Code as clear and detailed as possible (no need to aim at a small Tax Code) to limit the scope for decision-making of the Fiscal Service and tax inspectors.

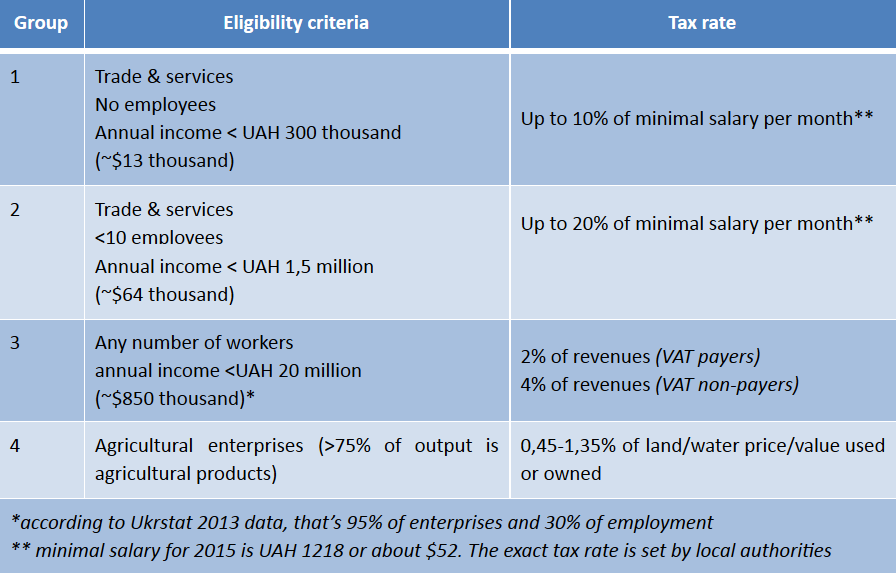

- When taxation procedures are sufficiently streamlined, leave only the fixed-tax part of the simplified taxation system (groups 1 and 2 from the table below) so that enterprises do not have incentives to stay small or to split – it is OK for business to grow, and large enterprises should not be punished for being large.

Annex. Simplified taxation system

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations