In 2017, 63% of Ukrainians believed that the government do not make efforts to reform the country. 77% of the population cannot name a single successful change. Most Ukrainians oppose liberal market reforms, such as land market or privatization. Ukrainian reformers tend to blame the Soviet mentality as an explanation. But that is not the case. In 1992 most Ukrainians were supportive of the land reform and privatization. That support was lost throughout the country’s post-soviet history.

The popularity of reforms and reformers has been studied in dozens of economic papers over the past decades. Ukraine appears in most of them. They show that the Soviet legacy, the population’s ignorance and populists’ myths are less to blame than is usually claimed. Yet the mass public dissatisfaction with the progress is the right way to lose another chance for success.

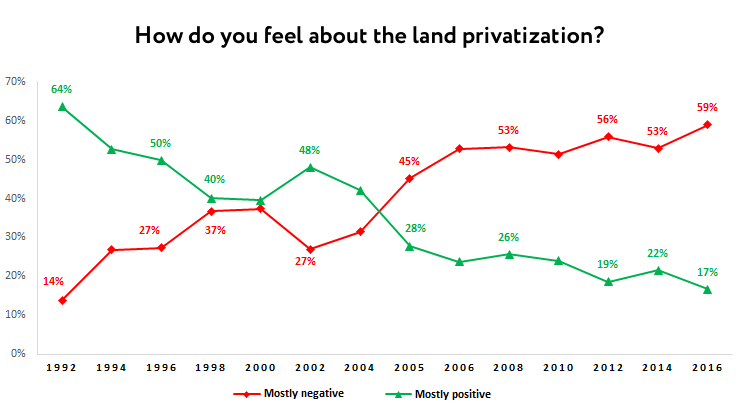

In 1992, only 14% of Ukrainians opposed creation of the land market. A decisive 63.5% supported it. In 2016, a totally opposite situation took place: a miserable 16.7% in favor while decisive 59% against.

Source: Results of annual national monitoring surveys

This is hardly consistent with the popular belief that Ukrainians oppose the land reform due to a rooted socialist legacy or the Soviet mentality.

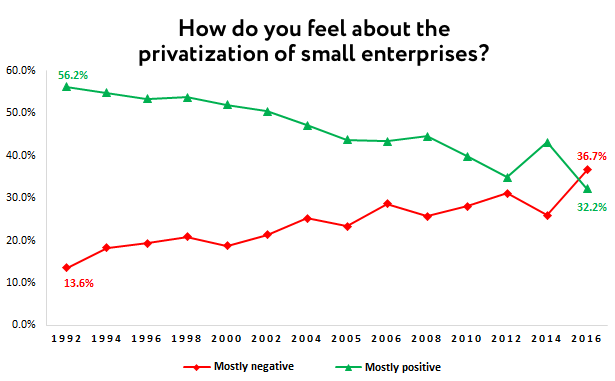

The same is true for privatization. State property reform, or privatization, began once the country became independent. Today it is still far from its completion, though almost every government put it on the priority list. One of the reasons is acute lack of public support. Except for 2014, small privatization kept losing support.

Source: Results of annual national monitoring surveys

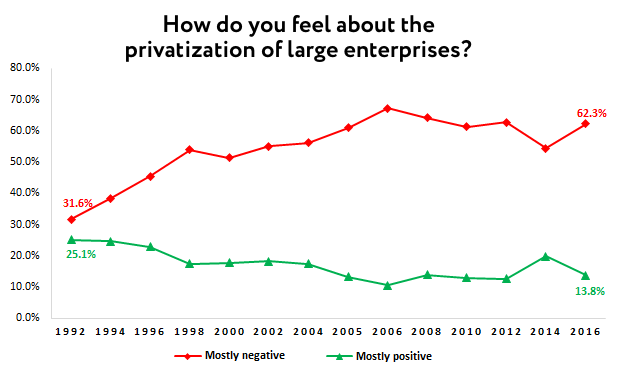

The opposition towards large enterprise privatization has always been higher than the support. Yet again, the opposition hiked twofold, support has fallen twice.

Source: Results of annual national monitoring surveys

Call for a strong hand. There is a dangerous increase in the number of citizens believing that “a strong leader who does not care about the Parliament or the elections is a good way to put the country in order.” In 1995-97 this thesis was supported by a little over 50% of the population; in 2010-14 – by 71%. For comparison, in Germany this kind of idea is supported by merely 20% of the citizens. In Russia, where it has been fully implemented, by 73%.

Why, then, the farther Ukraine moves away from the Soviet past, the smaller is the public support of market reforms and the higher support of authoritarianism as a cure?

To answer the question, we have analyzed studies of the subject. Two dozen papers underlying this article show that the reforms are unpopular mostly for economic and political reasons rather than the population’s ignorance or ideological bias. These reasons can be divided into two groups: economic and noneconomic ones.

Economic Reasons. Post-Soviet Pain Rather than the Soviet Legacy

Material losses. There is a close relationship between economic conditions and how people vote in reforming countries. There are those who win and those who lose in time of change. Those who expect to benefit from a reform, support it. Those who suffer, or expect to suffer later, oppose it. If the majority of population suffer during reforms, there will be lack of support. Voters punish government in favor of opposition if their financial situation deteriorated, and vice versa. The balance between positive and adverse effects of the reforms to a greater extent determined the political future of transition countries, rather than their differences in history, culture, or the scale of post-communist legacy (Fidrmuc 1998). Unemployment and inflation are the key factors causing material losses and affecting support for market reforms.

If a reform increases unemployment or the risk of unemployment, people tend to lower support for the parties associated with reforms and increase support for leftwing parties. On the other hand, private sector expansion increases popularity of reformers while bringing down support for communists and extreme left. Private sector employees traditionally more supportive of market reforms and low rate of state subsidies, whereas public sector employees and unemployed favor reforms only at the beginning. It defined by their expectations to get a better job in private sector as a result. If these expectations are not met, the reform support decreases while the preference for generous subsidies goes up (Fidrmuc 1997).

Those transitional countries that managed to keep inflation low experienced greater support for market reforms (Hayo 1999). Back in the 1990s, many transitional economies in Central and Eastern Europe faced severe crises, rising unemployment and inflation. Market transformations enjoyed great public support at the beginning of transition; yet in most of post-soviet economies that support was deteriorated or lost. Ukraine was among the countries severely hit by transition. Among all post-Soviet states of 1990s, Ukrainians gave the lowest estimates to economic and political systems of their country (Rovelli, Zaiceva 2011).

Economic shocks can interact with cultural preferences and determine citizens’ attitudes towards market economy and liberalization. The impact of crises on the population can lead to reform reversals and the country’s transition to a less liberal economic system.

One of the studies explored how the Great Recession changed the attitudes of Eastern and Western Ukrainians towards market economy and democracy. Residents from the East were more hit by the crisis, which decreased their support for market economy. This effect was stronger in areas closer to the border, which may suggest the interaction between economic and cultural factors. Western residents hit hardest by the crisis exercised greater disappointment with market economy and became more similar to their Eastern peers (De Haas et al. 2015). Economic shocks can undermine support for democracy as well as for market institutions and the government (Katz, Levin 2017).

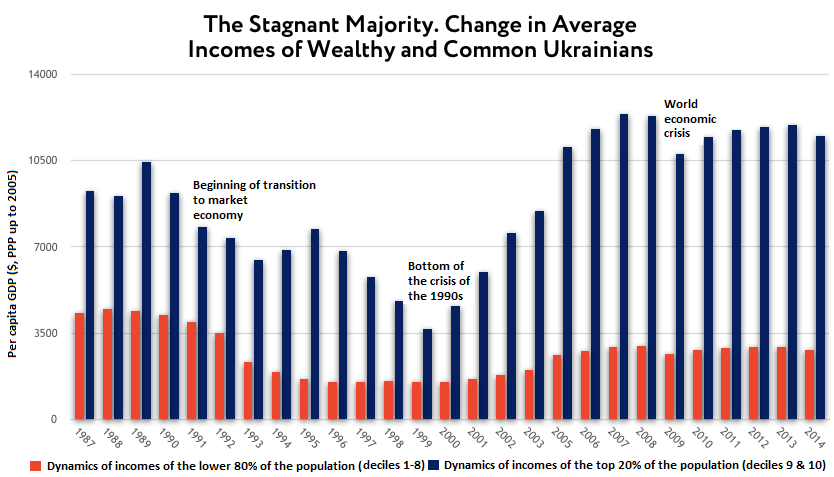

Inequality. Bulgaria, Russia and Ukraine experienced the most dramatic increases in income inequality among post-Soviet countries during the transition. Sharp losses by 80% of the population were accompanied by a significant gain among the richest 20% (Milanovic 1998). While incomes of top 20% have restored to pre-crisis levels, incomes of the lower 80% kept stagnating throughout the entire post-Soviet period.

When economic conditions and the standard of living improving, people tend to support larger-scale reforms. High inflation, living standards and inequality deterioration awakens nostalgia for the previous regime. Reduced life expectancy, high mortality rate, weak rule of law and widespread corruption enhance people’s yearning for the “stable” past (Golinelli, Rovelli 2011). Though leftwing ideas are popular in Ukraine, it is not a thing in itself; it may be a consequence of numerous other, non-ideological causes. The same factors keeping leftist ideas afloat bring down popular support for reforms.

Material losses, however, is not the only factor. As much important how people assess reforms and whether they trust the reformers.

Non-Economic Reasons

While economic losses by the population decrease the support for change, it is the crises that often unfold a public demand for change. In certain conditions, reformers can maintain high popular support while implementing hard measures. To succeed, they must be trusted and their policy must be perceived as just.

The Matter of Justice. Unfair Reforms are no Reforms at All

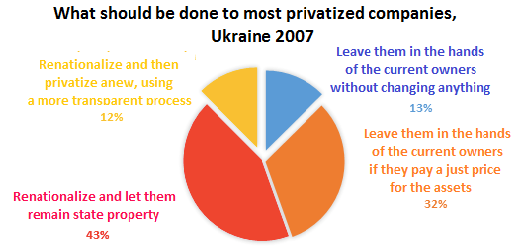

Perceived illegitimacy. A research involved 28 transition economies including all post-Soviet. More than 50% of the population of each of those countries (more than 80% of all respondents) support some form of privatization reversal, from additional taxes on the new owners to complete expropriation and renationalization of privatized enterprises. However, only 36% out of those 80% prefer state ownership. The remaining 64% prefer private property but want to revise privatization due to a massive dissatisfaction with its results.

Source: Denisova et al. 2010

Those who favor state ownership and deny to support privatization may have ideological or personal considerations for that. Others favor private property in principle, but oppose privatization due to unjust distribution of national wealth. People that suffered the greatest economic losses during the transition are least supportive of privatization and most frequently favor revising its results (Denisova et al 2010).

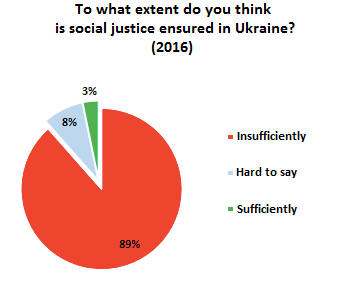

Inequality fair and unfair. Although the income inequality sharply increased during post-Soviet transition, Ukraine has a relatively low inequality rate compared to other countries. A 2009 survey shows, however, that more than 90% of Ukrainian citizens overrate inequality, believing it is much higher than it actually is. In 2009, the Gini coefficient for Ukraine was 28 points, placing Ukraine among the 30% of countries with the lowest inequality index. However, according to the Ukrainians’ assessments, the coefficient should have been 39 points, which would have placed Ukraine among the 30% of countries with the highest inequality level in the world (Gimpelson, Treisman 2015). Such differences between perception and reality may be related to whether people consider inequality as fair and wealth of the rich as deserved.

Source: Results of annual national monitoring surveys

People do not oppose inequality when it is clear that the rich have deserved their wealth working harder or mastering better skills (Breza et al. 2016). If they believe the rich have made their fortune in a doubtful way, inequality is perceived as injustice. Only this “unjust” component of inequality, i.e. income inequality due to the different opportunities adversely affect the support for reforms. If someone becomes rich owing to a privileged position in society, parents’ connections, access to better education, etc., others tend to regard this as unfair (Guriev 2018).

Factual inequality hardly affects people’s belief that the government should alter income distribution. Perceived inequality this is what strongly correlates with public desire for redistribution and demand for leftwing policies. It is considered as a way to restore justice (Gimpelson, Treisman 2017). And neither education nor public informing can resolve the problem. People do not give up the misconceptions of inequality even facing with contrary facts.

The Matter of Trust

Ukrainian political parties often protect the interests of influential groups. Therefore, people neither trust the parties nor identify themselves with them. Citizens not feeling that parties represent and protect their interests reduce support for democracy. As a result, the younger generation of Ukrainians has considerably less confidence in political parties compared to the older one (Reshetova 2011). If you think that the politicians cheat you and so you will get higher prices while all the benefits will go to the privileged ones, then the opposition to change will be quite a rational behavior (Fernandez, Rodrik 1990).

In its turn, a high level of social distrust creates a political demand for excessive state regulation. This relates to interpersonal trust as well as to public trust in business, politicians, and political institutions. In highly distrustful countries people tend to favor strong state intervention even when realizing how corrupt the state is (Aghion et al. 2009).

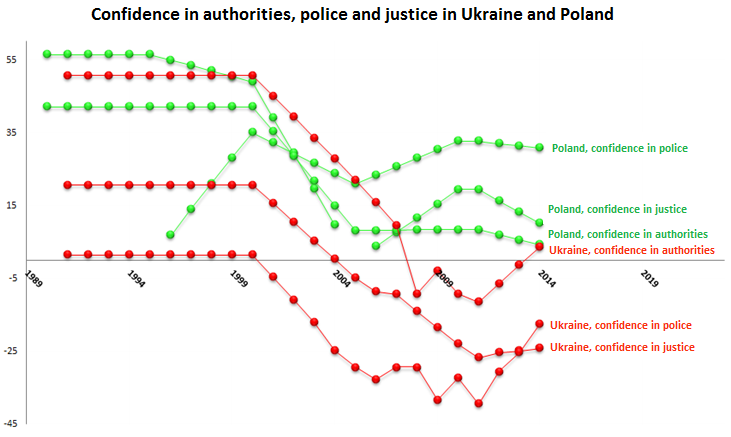

During Ukrainian post-Soviet period the citizens’ confidence in authority, police, and justice has dramatically declined. This was often observed in other post-Soviet countries, although, to a lesser extent. For example Poland: although trust in its institutions kept decreasing, the percentage of trusting citizens was always higher than that of the distrusting ones. In Ukraine, a more dramatic picture observed: since the mid-2000s, the number of citizens distrusting the above-mentioned institutions has almost always been higher than the share of those trusting.

Source: The Democracy Barometer

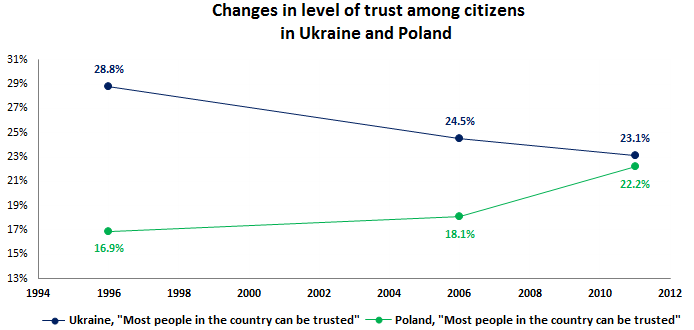

As to interpersonal trust in Ukraine it kept declining during the entire post-Soviet time. In Poland, historically, even fewer citizens replied that most compatriots could be trusted. However, the opposite trend was observed: the level of trust kept increasing in the post-Soviet period.

Source: World Values Survey

One of the key factors determining citizens’ trust towards each other and political institutions is economic growth (Kroknes et al. 2015). Economic crises lowering trust among people, destroying cooperation mechanisms and adversely affecting the economic policy choice. Contrariwise, economic growth and political system effectiveness form citizens’ demand for policies conducive to growth, enhance support for democracy and strengthen confidence in political institutions.

When Hard Change can be Popular

Economy and justice. Most of the population must feel that they will benefit from the change. The redistributive effects of each reform must be considered. If changes hit many people hard, compensatory mechanisms for the most vulnerable should be proposed. Economic growth, lower income inequality, and a higher quality of public administration enhance the level of support.

In addition to material aspects, reforms must carry a symbolic significance. People have to feel that the reforms are being implemented for them and in their favor, not at their expense and in favor of the chosen few. There are reforms painful and unclear to the public. There are reforms painful and risky for the beneficiaries of the unfair status quo. If only the first are implemented while the second are postponed until the next political season, there will be no support. No public approval will be gained if while reforming an extremely unfair society “the bad guys” in the image of oligarchs or corrupt politicians do not lose. Not only will citizens provide no support to such reforms; they may even refuse to recognize them as such.

The Ukrainian lesson

Increasing energy tariffs and the exchange rate liberalization are not regarded as reforms by majority of the population, despite all their importance and lack of alternatives. Every common citizen can personally feel their negative consequences in the form of rising prices and falling living standards, while potential benefits remain unclear. On the other hand, delays and failures in anti-corruption and the rule of law dimensions together with slow motions in the quality of public service make the average citizen believe that the current pain will not pay off as tomorrow’s gain; or that his/her own pain will be someone else’s gain.

Due to the transition experience of post-Soviet countries, the popularity of political reforms always prevails over the popularity of economic ones. Power limitations of corrupt politicians increases support for market transformations. Restricting the power of civil servants and allowing voters to monitor, reward or sanction politicians for wrongdoing enhances the legitimacy of the reformer. Such actions convince the voter that the fruits of change will be distributed broadly rather than to the leaders’ associates.

The country has overcome a number of massive protests. Their slogans say that the citizens associate justice rather with combating elite’s abuse of power and restoring equal opportunities in the society rather than with left-wing socialist-style policies.

What prevents the authorities from implementing reforms, 2016

Source: Institute of Sociology of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine

Confidence in the reformer. If people do not support a reformer, they will not either support a reform. In the absence of a popular leader, a complex reform is vulnerable. Reputation of the leader defines support for a policy that concerns citizens but is not quite clear to them. If citizens do not know or do not trust the leader, their opinion on the policy is susceptible to manipulation.

Balancing between painful and popular changes, taking into account the aspect of justice, and maintaining public trust are what the first wave of Ukrainian Post-Soviet reforms was lacking. This is what it lacks today. Neither the data nor the research support the popular idea that the socialist past is the main reason behind the popularity of anti-market attitudes in post-Soviet Ukraine. The dismal economic history, the discredited political system, the disgraced word “reform” are better explanations. Moreover, if reforms are unpopular due to its design rather than the human mentality, it may be handled. There is a high risk, however, this will be possible next time.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations