A wave of populism has been gaining ground in the West since 2012. This column uses regional data for 26 European countries to explore how the impact of the Great Recession on labour markets has affected populist voting, political attitudes, and trust. The results indicate a strong link between unemployment and voting for non-mainstream (especially populist) parties. Unemployment is also correlated with increasing distrust of national and European parliaments.

A spectre is haunting Europe and the West – the spectre of populism. The UK’s vote to exit the EU and the US elections in 2016 have served as a wakeup call to Anglo-Saxon elites. In continental Europe, the first significant successes of anti-establishment politicians came even before the French presidential elections and the German elections of 2017 (where Front National and AfD obtained considerable vote shares). Populist parties in Austria, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Sweden, Spain, and the UK have been gaining substantial ground since 2012.

Firstly published at VOX CEPR’s Policy Portal.

The recent wave of populism is different from the previous wave that was mostly concentrated in Latin America (Dornbusch and Edwards 1991, Acemoglu et al. 2013). As argued by Rodrik (2017), the current wave is not driven so much by a left-wing demand for redistribution; instead, it is related to the rejection of globalisation (trade integration, financial globalisation, and immigration). This issue is prominent in the agenda of both radical-left and extreme-right parties. It seems that the left–right divide is being replaced by the confrontation between parochial and cosmopolitan values (De Vries 2017). At least to some extent, this has been driven by the vulnerability of the lower-middle classes to job polarisation caused by trade and technological progress, which in turn has brought up outsourcing and increased competition from low-wage countries, and automation (Autor et al. 2017, Colantone and Staning 2016, Becker et al. 2017). On top of these medium-term developments, economic insecurity in Europe has increased in the aftermath of the Global Crisis as unemployment has grown substantially. And despite the European recovery and declining labour force participation, unemployment is falling quite slowly, especially in the South.

In our recent paper, we study the labour market impact of the Great Recession on populist voting and political attitudes and trust in Europe (Algan et al. 2017). We conduct the analysis at the regional level, exploiting time variation in unemployment, voting, and attitudes/beliefs in more than 220 regions in 26 European countries in 2000-2017.

Unemployment and voting for non-mainstream parties

We start analysing the relationship between voting for non-mainstream parties and the change in unemployment before and after the financial crisis of 2007-2009. We assign non-mainstream parties into four (not mutually exclusive) categories:

- Far right (e.g. Golden Dawn in Greece)

- Extreme left (e.g. Syriza in Greece, Podemos in Spain)

- Populist (e.g. UKIP in the UK, the Five Star Movement in Italy)

- Euro-sceptic (e.g. UKIP in the UK, Jobbik in Hungary).

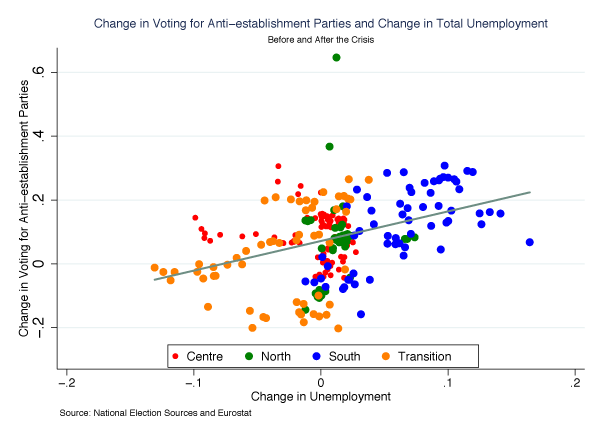

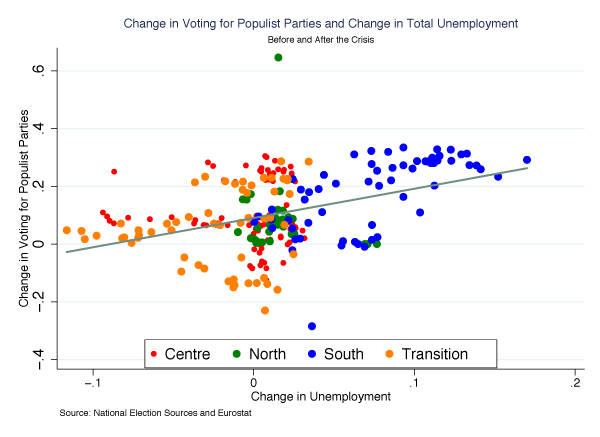

We find a strong link between increases in unemployment and voting for non-mainstream (especially populist) parties. Figures 1a-1b illustrate these patterns. The estimated magnitude is considerable – a one percentage point increase in unemployment is associated with a one percentage point increase in the populist vote. The effects are strongest in the South, but the relationship is also present in the East and the Centre; it is not significant in the North. Interestingly, in the South we observe a tight association between unemployment and voting for radical-left parties, while in the North unemployment correlates with voting for far-right and populist parties – a pattern that is also present in Eastern Europe, where people are turning their backs on communist and far-left parties and moving to xenophobic and anti-European parties.

Figure 1a Change in voting for anti-establishment parties and change in total unemployment, before and after the Crisis

Figure 1b Change in voting for populist parties and change in total unemployment, before and after the Crisis

Our methodology accounts for time-invariant regional factors (related to geography or culture) and general time trends (pan-European or across four groups of countries); however, the estimates may pick up some unobserved or hard-to-account-for regional time-varying variables. In order to advance on the identification of the causal effect of unemployment on populist vote, we extract the component of (or ‘instrument’) the change in unemployment over the crisis explained by the pre-crisis share of construction. Construction and real estate played a major role during both the build-up and the burst of the crisis around the world. And the construction share correlates positively with rising unemployment post 2008-2009. We find a strong effect of an increase in unemployment on the rise of populism. We check alternative explanations of the construction-unemployment-voting nexus and find that it does not seem to reflect other time-varying regional variables, such as immigration, corruption, or education.

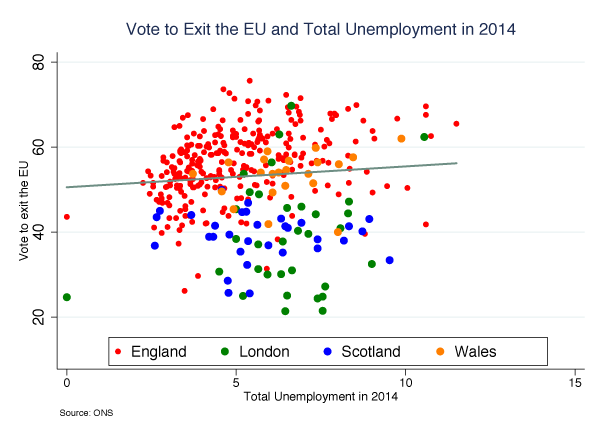

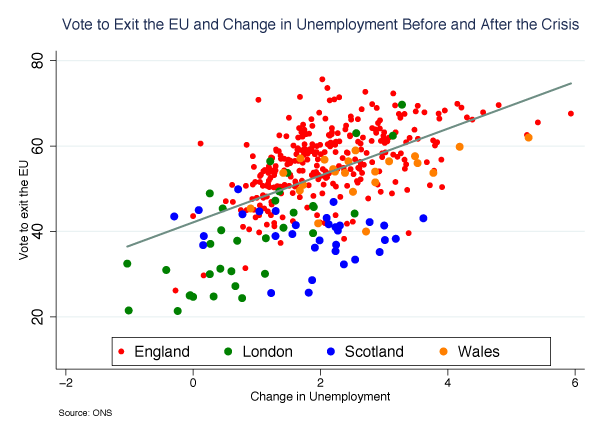

We then use the vote by UK citizens in the June 2016 referendum to leave the EU as an ‘out-of-sample’ test of the Europe-wide results (for a thorough analysis of the correlates of the Brexit vote, see Becker et al. 2017). The results, summarised in Figures 2a-2b, show that increases in unemployment during the crisis period (2007–2015) – rather than the level of unemployment in 2015 – are strong predictors of voting for Brexit. We find similar results when we instrument changes in unemployment with the pre-crisis share of construction across the UK’s 379 electoral districts.

Figure 2a Vote to exit the EU and total unemployment, 2014

Figure 2b Vote to exit the EU and change in unemployment before and after the Crisis

Unemployment and political attitudes

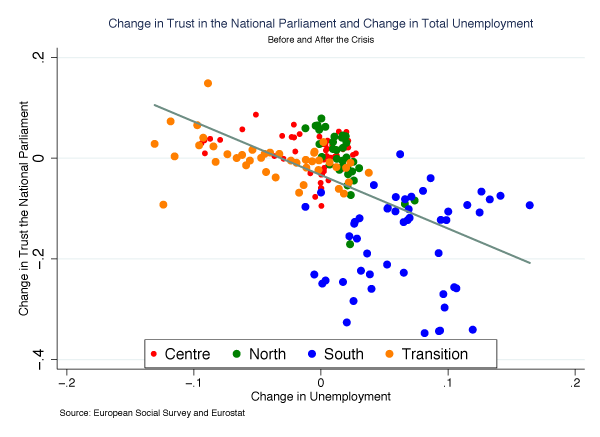

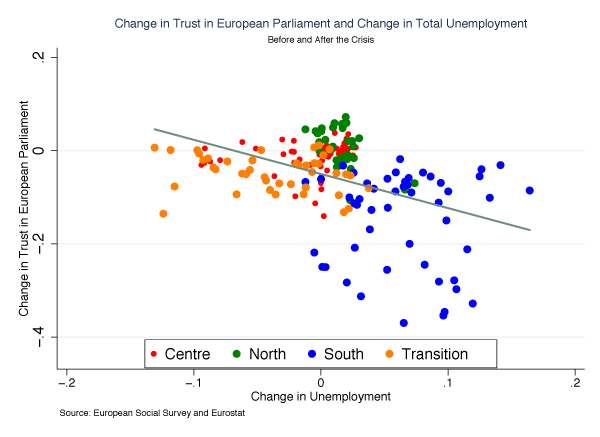

Second, we try to identify the channel through which economic insecurity affects voting outcomes by looking at individual-level data on Europeans’ beliefs and attitudes from the European Social Survey covering the period 2000-2014. Similarly to the concurrent papers of Guiso et al. (2017) and Dustman et al. (2017), we find that an increase in regional unemployment results in a significant decline in confidence in national and European political institutions and, to a lesser extent, in trust in courts. Figures 3a-b illustrate these post- and pre-crisis patterns.

Figure 3a Difference in trust in national parliament and difference in total unemployment, before and after the Crisis

Figure 3b Difference in trust in the European Parliament and difference in total unemployment, before and after the Crisis

The analysis uncovers some additional regularities. The association between unemployment and general trust is weak and not statistically significant in most specifications. Also, unemployment does not correlate with distrust in the police or the UN, suggesting that Europeans blame the rise in unemployment on the European and national political establishments. So it is not surprising that in regions with the largest increases in unemployment, voters support populists in national elections (Algan et al. 2017) and report a higher vote for populists in European elections (Dustman et al. 2017). This also explains the increased supply of populist rhetoric and policies offered by new and even old parties (Guiso et al. 2017). We also find that unemployment does not correlate with respondents’ political self-identification on the traditional left–right axis. Also, despite the fact that many new parties have emerged, respondents in crisis-hit areas are more likely to report that no party is close to their views.

We also examine the impact of unemployment on beliefs about whether European integration should go further or whether it has already gone too far. On average, changes in unemployment are not related with the view that the EU has gone too far nor with attitudes that the EU unification should proceed. However, this average non-result masks heterogeneity. In the South, increases in unemployment are correlated with aspirations for deeper integration. In contrast, in the North and in the Centre, in more crisis-hit regions respondents believe that the European project has gone too far.

The results hold for both men and women, for younger and older cohorts. The relationship between unemployment and distrust in national and European institutions is stronger for non-college graduates. This result is in line with the findings of Autor et al. (2016, 2017), Che et al. (2016) and Colantone and Stanig (2016), who relate populist voting and political polarisation to depressed wages among unskilled workers fuelled by rising competition from low/middle-income countries.

Policy implications

Our results imply that increased unemployment results in loss of trust in political institutions and in increased support for anti-establishment populists. To reduce unemployment, European policymakers were forced to pursue unpopular structural reforms, sometimes amidst massive austerity policies. However, reforms require people’s trust – voters need to be confident that the future gains from painful reforms will be shared broadly rather than captured by selfish economic and political elites. If there is no trust in the political system, reforms cannot be easily implemented – and unemployment will remain high. At the same time, the rising distrust towards courts is alarming, as legal institutions are pillars of Western democracies and capitalist societies. The current momentum of recovery in the European economy offers a chance to break the vicious unemployment-distrust-populism circle. This opportunity should not be missed.

References

Acemoglu, D, G Egorov and K Sonin. (2013), “A political theory of populism”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 128(2): 771.

Algan, Y, S Guriev, E Papaioannou, and E Passari (2017), “The European trust crisis and the rise of populism”, CEPR, Discussion Paper 12444, forthcoming in Brookings Papers on Economic Activity.

Autor, D H, D Dorn, G H Hanson and K Majlesi (2016), “Importing political polarization? The electoral consequences of rising trade exposure”, MIT Department of Economics, Working paper.

Autor, D H, D Dorn, G H Hanson and K Majlesi (2017), “A note on the effect of rising trade exposure on the 2016 presidential elections”, MIT Department of Economics, Working paper.

Becker, S O, T Fetzer and D Novy (2017), “Who voted for Brexit? A comprehensive district-level analysis“, Economic Policy 32(1).

Che, Y, Y Lu, J R Pierce, P K Schott and Z Tao (2016), “Does trade liberalization with China influence US elections?”. NBER Workgin Paper No w22178.

Colantone, I and P Stanig (2016), “Global competition and Brexit”, BAFFI CAREFIN Centre Research Paper, No 2016-44; forthcoming in American Political Science Review.

Colantone, I and P Stanig (2017), “The trade origins of economic nationalism: Import competition and voting behavior in Western Europe”, American Journal of Political Science, forthcoming.

De Vries, C E (2017), “The cosmopolitian-parochial divide: What the 2017 Dutch election result tells us about political change in the Netherlands and beyond”, Journal of European Public Policy, forthcoming.

Dornbusch, R and S Edwards (1991). The Macroeconomics of Populism in Latin America, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL.

Dustmann, C, B Eichengreen, S Otten, A Sapir, G Tabellini and G Zoega (2017), Europe’s trust deficit: Causes and remedies, Monitoring International Integration 1, CEPR Press.

Guiso, L, H Herrera and M Morelli (2017), “Populism: Demand and supply of populism“, Einaudi Institute for Economics and Finance (EIEF), Working Paper n°1703.

Rodrik, D (2017), “Populism and the economics of globalization”, NBER, Working Paper No w23559.

Main photo: depositphotos.com / microgen

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations