‘Equal conditions for all’ is not a bad idea. However, as I explained in previous articles, it should be first realized with respect to the general system. As long as the latter is repressive, discretional, unfair and full of really large leakages, there is no point in harmonizing the STS with it – simply because as of now it is much healthier in itself. Instead, wouldn’t it be better to make an opposite harmonization – try to make the general system equally simple in use, straightforward, predictable, corruption-proof, and equal for all?

The Past, Present and Future of Simplified Taxation: Debunking the Myths

I have already emphasized that the discussion around tax reform should be focused on the primary issues, with priorities set according to the magnitude of problems – which means, in particular, that the simplified taxation system (STS) should be kept intact at least for the moment. Unfortunately, while this article was in process, the MinFin came up with a proposition on the emasculation and further actual elimination of simplified taxation for all firms and entrepreneurs that have a turnover above 300,000 UAH, through forcing accounting of business expenses with a 12% turnover tax along with cash registers. This proposition has actually become the most radical and most discussed topic of the whole tax reform offered by the MinFin. Maybe it was made according to Parkinson’s law of triviality, as I suggested in one of my previous articles; maybe there were political-economic reasons behind this decision as described below and before hand. All in all, there are few other issues, even within the realm of the Ukrainian tax system, that bring about as many misconceptions and as much anger as the STS does. Such misconceptions, usually based on biased or simply anecdotal evidence are, unfortunately, common for many tax experts and economists, so it is a time to fill the gap. And because the MinFin brought this issue to the fore, it now requires a thorough analysis. A good background for such an analysis was recently prepared by the USAID LEV program [1] – this article is largely based on it, however my interpretations of the results may differ from the ones provided by its authors.

In brief: small (especially, micro) business has its own peculiarities that make simplified taxation necessary and socially desirable. Moreover, even some reduction in the tax burden for it can be, arguably, justified as a compromise for bringing it out of the shadow. But, most importantly, the STS is the only departure from the rule of “selective implementation of the impracticable norms” that plagues the rest of the Ukrainian tax system. It was deliberately made as simple and straightforward as possible in order to avoid any discretion or excuses for repressing the entrepreneurs. Its main advantage is that while paying taxes, the payers rarely know their inspectors in person; an inspection is a “special case”, not a matter of everyday life; the rules are simple, formal, straightforward, and uniform; very few of the entrepreneurs subject to this system complain about extortion and unfair treatment. Still, it is not without problems mainly because co-existence of two tax subsystems in one economy with notably different tax bases almost inevitably creates opportunities for legal tax minimization. They should be restricted to a possible extent, but not “at any cost”, certainly not by adjusting of simplified taxation to the worst features of the “general” system.

It is like a building of 15 rooms with a terrace. The building is quite heavy (high tax burden), but the main problem is that it was designed by the mainstream architects that had not even tried to explore the soils, just copied some Western examples. Meanwhile the ground appeared to be weak and shaky for the whole construction. No surprise that this building is falling apart, and needs permanent maintenance that makes it increasingly ugly. At the same time, the terrace is lighter, better suited to the ground, and looks much healthier if just taken alone. And, yes, there are pretty large cracks between it and the rest of the building – although they are hardly comparable to the ones in the main building.

Now the main building is falling apart, it threatens to bury its inhabitants, and the same or similar architects that developed the initial design come to look for a fix. They glance at the construction, and the first thing that strikes them is the terrace – because its appearance conflicts with the rest of the building, and with these architects’ tastes of harmony. Respectively, they advise to somehow tie the main walls with braces (again, ignoring the ground and fundamentals), paint over the gaps, and destroy the terrace because it irritates them… While they do find a few good reasons to justify it, they fail (or refuse) to respond to the counter-arguments.

But is this parable really right?

Why a simplified tax?

There are a number of reasons in favor of a special simple tax for micro business [2] that are common for most of the World. This is why such kinds of tax arrangements exist in many countries.

The first of these reasons is universal, since it is related to the very nature of a micro business: for purely business purposes it rarely needs accounting or even bookkeeping. Indeed, these are primarily business tools (not the fiscal ones!) that were developed for the owners and top managers in order to help them control their firms when they outgrow a certain level that makes direct overseeing of the operations difficult. In this sense, the respective expenses are justified, although they should be still classified as transaction costs. However, as soon as a micro business normally does not need them – it is a part of its overall advantage of negligible administrative costs – savings on this item partly compensate for the lack of economies of scale, and, among others, allows small business to be competitive.

In the meantime, net income taxation can exist only in the form of declarations that should be supported by some duly kept books and duly collected primary documents (such as cash receipts) in order to make further inspection possible. Therefore, an entrepreneur should spend a substantial portion of her time for keeping records, etc., or hire a specialist for this. Moreover, even fully literate and trained persons are not necessarily able to make it accurate enough: this requires certain skills and capabilities that many people just lack. Also, it creates a permanent ground for cavils and consequent fines. This is especially true due, again, to the very nature of a micro business where the business costs are often hardly dispensable from the household’s ones – just think of a taxi driver that uses his own car for dual purposes. Finally, the cost of tax compliance (including the bookkeeping and accounting) is highly regressive. In Ukraine, according to IFC estimates, it can reach 8.2% of revenue for firms with up to UAH 300 thousand annual sales [3], which is substantially higher than the taxes such firms have to pay.

Simplified taxation in the form of a lump-sum tax (as at the Tier 1 and Tier 2 of the Ukrainian STS) is a simple solution that allows the taxpayers to get rid of unnecessary bookkeeping. A primitive record of sales is needed only in order to make sure that total turnover remains within a limit stipulated by the law. In fact, this recording still does not guarantee anything, so a few other methods are needed (they will be discussed below). But what is most essential, is that lump-sum taxation requires no record on expenses and no primary documents. This is especially important for small vendors that sell a high variety of goods in small quantities. For those entrepreneurs that sell to legal entities – thus, receive not cash but wired transfers – a turnover tax (as under Tier 3) is almost equally simple, since all their revenues can be calculated by a couple of mouse clicks. In the meantime, their turnovers can be equally easily checked by tax authorities at a distance, so no inspections are normally needed.

In such a way, according to the calculations made by the USAID LEV program, the STS in Ukraine saves about 0.5% of the GDP (approx. UAH 7 billion in 2014) that otherwise would have been wasted [4] for unnecessary work. Also, it partly levels the playing field for large and small business (otherwise the latter would have to bear a relatively higher compliance cost), reduces the barriers to entry, and allows for substantial but hardly assessable savings on administrative costs of the fiscal authorities that otherwise would have to inspect every small vendor.

Notably, simplified compliance is not a tax privilege in itself, and is not necessarily supposed to become one. However, since the simplification often leads to narrowing of the tax base at least because the simplified system attracts mostly those for whom it is also economically beneficial, de facto a simplified tax can become a privilege. Still, there are a couple more reasons that justify not only simplification, but also even some privileging of a small business.

In many countries, small, particularly new-born, enterprises are privileged due to their key role in the Schumpeterian entrepreneurship. Even giants like Apple, Google, Toyota, Samsung, and many others once were undertaken as micro businesses. For this reason, start-ups are being nursed, provided with tax holidays etc, because they may later on mature and bring some new ideas, corporate culture, and other innovations that feed growth and wealth. This is, of course, true, and especially important for Ukraine and other transition countries that still lack entrepreneurship as a full-fledged process of vertical mobility in business.

However, in fact only a small portion of micro enterprises have any capacity to grow. This is natural, since the size of a firm is eventually determined by entrepreneurial talent of its owner(s), other things being equal, while the latter should be expected to be Pareto-distributed. Thus, the majority of small and micro firms will never grow into larger ones; a lot of them will just provide subsistence for entrepreneurs. They are poorly governed compared to those who managed to grow; respectively, their productivity and competitiveness leave much room for improvement; they have no potential to become “gazelles”. For all of these reasons, several Economists see no reason for their existence at all [5] and even prefer unemployment benefits.

Nevertheless, many countries that have unemployment benefits in place usually do their best to support even the subsistence of small businesses, as they absorb potential unemployment. These entities, even in spite of their low productivity, still generate some value, and have their own niches that are not attractive enough for larger and more productive entities. In the meantime, the alternative to them is either unemployment, which is not productive at all (and creates numerous traps, negative externalities, etc.), or – in case of elastic labor market – low-productive low-paid workplaces at larger firms. From a fiscal viewpoint, even some easing of the tax burden for low-productive micro business is justified because it helps to save on unemployment benefits while still generating some revenues (this is, in a way, akin to consumer discrimination made by a seller).

The next reason is most acute in poor and institutionally weak countries: it is the compromise on de-shadowing. However high the penalties are, and however totalitarian the control is, no government in the World can eliminate the shadow economy completely. There is always a line where more or less-wise governments should change a stick to a carrot and offer some acceptable conditions for those who like to work officially. As in the previous case, it is better to collect something rather than nothing, especially if (as in the case of simplified taxation) it does not incur any substantial administrative costs. Besides, the shadow economy has lots of negative side effects and spillovers, like deterioration in public morale, corruption, rackets, etc., that are diminished if the business pays some symbolic tax for staying legal.

Finally – and primarily – simplified taxation shelters the micro business from extortion by tax officials. As I already explained in previous articles, the Ukrainian tax system is highly discretional, it allows for extortion “in the name of law” – under the threat of enforcement of impracticable law. Moreover, this extortion tax is regressive, since small business normally has less negotiating power than a larger one. For this reason it is mostly subversive for small, and, especially, micro business. Simplified taxation in the form of a “single tax” that allows for zero discretion at least for the most problematic taxes it replaces has appeared to be a very effective remedy for this problem. Historically, this feature of the STS played a major role – both in its creation and in the further attempts to curtail it.

Brief history of the STS

The simplified tax was introduced in 1999 as a part of deregulation package mainly in order to shelter small business from discretion (hence, extortion) of tax authorities and get it paying more to the budget instead. Both goals were achieved successfully by 2004 or so, as there were already a few million genuine middle-class people that played a decisive role in the Orange revolution. During the 2000s, the real value of lump-sum tax (as well as upper bounds for using the STS) was eroded by inflation so it soon became a privilege, which made it subject to abuses (see below), particularly from the larger firms’ side. In 2010, these abuses were used as an excuse for attempting to curtail the usage of the STS and emasculate it by Yanukovich-Azarov’s government – although in deed they, perhaps, mainly tried to destroy the middle class as a political-economic basis for democracy and competitive market economy. This attempt resulted in an uprising (the current version of the STS came as a compromise after it) and the loss of more than two million workplaces in small business. (Detailed history can be found here)

Unlike its predecessors, the contemporary government was brought to the power by the Maidan. It seemed that to hit those who paved its way to power is probably the last thing to do from a political viewpoint. However, nowadays we witness a new attempt on simplified taxation that is potentially not less detrimental to it. Noteworthy, as usual, is that complaints on violations involving simplified taxation arise as the “tax laundry” becomes under attack: the incumbents having vested interests in the acting system gladly direct the reformers for fighting simplified taxation. Among other things, this is because the reforms here are most unpopular, so have little chance of being implemented. Of course, officially the MinFin again justifies its propositions with alleged “major abuses” related to the STS. But are these abuses indeed that terrible?

Abuses of the STS: how important are they?

Abuses are inherent to any tax system or its part. They, of course, should be fought, but the measures against them should be cost-effective. Such costs include (but are not limited to) administrative expenses for control and inspections; damage to the compliant payers; risks of corruption and other abuses of control – for, say, political repressions, mowing the markets for cronies, etc. Besides, one should take into account that a fiscal effect means only more effective redistribution, not a welfare gain; meanwhile the costs are often net losses. So, for instance, if wasting of one Hryvnya on tax compliance and enforcement helps to raise five Hryvnyas in budget revenues, it is economically productive only if the government can use this money 20% more efficiently than a taxpayer. On the other hand, of course, tax avoiding also brings numerous negative spillovers.

Abuses of the STS are very evident. People only need to read about an oligarch hiding billions of USD from taxation in the tax havens, or about a crook organizing “tax laundries” of equal size. Even when people get paid in envelopes themselves, they rarely think about the source of cash for this payment. At the same time, many of us personally know a guy that actually works as an employee but is being paid as an entrepreneur; or a genuine entrepreneur with many millions of annual sales that pays only a few hundred UAH monthly as his single tax. Still, all of these facts are just anecdotal evidence. What is the real picture?

The STS is indeed abused “from outside” by larger businesses that use it for avoiding labour taxes. In particular, it is sometimes profitable for larger firms to split apart in order to benefit from the STS’s relatively low rates, or for employers to register their employees as individual entrepreneurs. Particularly, such splitting could be one of the reasons for growth (in this case – artificial) of a number of business entities in the 2000s, especially after the employers subject to the STS were obliged to pay the PIT and payroll taxes for their employees in a regular way (initially they paid half of their own lump-sum rate for each employee), which also made the employers subject to more inspections and related discretion. Also, simplified taxation is used by smugglers because absence of bookkeeping does not allow for customs’ post-audit. All in all, perhaps, abuses of simplified taxation should be considered the third important tax loophole, after tax havens and “tax laundries” as described in one of the previous articles. The LEV study estimates the abuses related to avoidance of the labor taxes as 6.3 billion UAH (here and after – in 2013) [6], which constituted about 0.4% of the GDP, that is just 10% less than the entire revenues from the single tax. In the meantime, it is about ten times less than, for instance, the VAT abuses estimated at 50-70 billion UAH for the same year.

Besides, the STS is being abused from within. As long as no effective control over the real volume of sales is in place, the taxpayers can relatively easily under-report their turnovers. This makes little sense for the payers of lump-sum tax (Tier 1 and 2), since in such a way they cannot reduce their tax liabilities – with one but important exemption. Namely, those whose volume of sales exceed a limit making them ineligible for using the respective STS regime, have a strong interest to cheat, since otherwise they would have to pay more. This is particularly important for the upper limit of Tier 2, where a taxpayer enjoys maximal benefits of actual regressiveness of the lump-sum tax, while on Tier 3 she has to pay 4% of total turnover. In the meantime, an incentive to conceal sales within Tier 3 is again lower, because it can save only 4% of the concealed volumes. Therefore, one should expect several abnormally high numbers of entrepreneurs reporting the turnovers close to the upper limit of Tier 2, while probably making more in reality. But what is “high” and what is “close”?

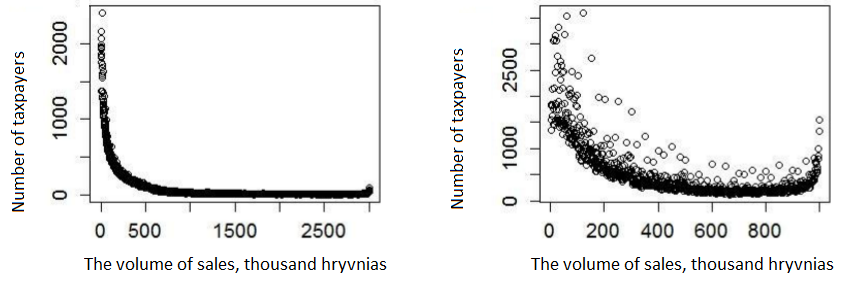

Normally, undistorted firms’ distribution by size strictly follows the Pareto one [7]. Any deviation from this rule signals about some problems. Therefore, if we plot the number of firms that reported volumes of sales within some narrow range against these volumes, then the excess above the Pareto curve will give us the estimation for a number of entities that exceed the limit. Using this method, the LEV study has found that about 28 600 entitles (or about 5.4% of all entrepreneurs that use the Tier 2 of the STS) can be suspected of this – although, perhaps, many of them report honestly, and just do not like to grow beyond it, so this number should be treated as an upper estimate (see Figure 1). Also, slightly smaller number of entities declared approximate (round) numbers, which looks somewhat suspicious, but most probably just means that the entrepreneurs were not accurate enough in recording their sales – since it does not affect their tax liabilities anyway. But for this very reason these violations are minor and can hardly result in any significant revenue losses for the government. All in all, the concealed turnovers were estimated at 7.8-13.2 billion UAH [8] above the declared ones, so all together up to 40 bln. UAH. Given that otherwise these entrepreneurs would have to pay 4% at the Tier 3 of the STS, the fiscal losses incurred by these abuses can be estimated within 1.6 billion UAH.

At the same time, for Tier 3 (where any misreporting does mean tax evasion) the distribution is almost exact, apart from a tiny excess close to the upper limit – although, of course, it does not necessarily mean that there are no abuses at all. Still, even the opponents of the STS do not provide any evidence for major and systemic under-reporting on the Tier 3. Thus, the problem is, probably, limited with the number above.

Figure 1. Distribution of the taxpayers of Tier 2 and Tier 3 of the Ukrainian system of simplified taxation by the reported volumes of sales in 2014. Data: State Fiscal Service of Ukraine, by a special request. Estimation: the USAID LEV study.

Therefore, the research shows that under-reporting at Tier 2 does exist (did anybody expect the opposite?), and it does involve thousands of taxpayers. However, fiscally it is not very important. Which, in turn, means that the most cost-effective way to address this problem is a targeted intervention, as opposed to a crackdown on the STS as such, or any massive attack on the possible abuses, like mandatory use of cash registers.

The latter case is a good example of the damage that incorrect approaches based on anecdotal evidence can incur. Total (direct and implicit) cost of buying, installing, and servicing of cash registers by the Tier 2 taxpayers in a first year was estimated by the State Regulatory Service of Ukraine (SRSU) at 37 billion UAH. This figure is criticized, maybe at least partly fairly. But even assuming that this estimation is overstated by three times (no more, since the least expensive register currently recognized by tax authorities and actually available in Ukraine costs about $200 alone, not to mention other costs), this is still dozens of billions UAH of waste. Of course, this number will be lower just because the economy can adjust. Namely, a few hundred thousand entrepreneurs for whom the respective cost is unbearable will have to go out of (official) business and fire their employees, just like what happened in 2010. They will either have to look for jobs (which are scarce due to the crisis), or to seek a social benefit, or just go to the shadow. At the same time, those who will install the registers will not necessarily pay more taxes – there are lots of tricky ways for evasion, especially in a country as corrupt as Ukraine. Nevertheless, the MinFin’s tax reform stipulates mandatory use of cash registers starting from 1.06.2016 for all entrepreneurs having more than 300,000 UAH as annual sales, and for everybody (including the open market and street vendors, for which it is not technically possible!) starting from 2019. Is such a measure cost-effective in fighting the abuses that are many times less in volume that the cost of their fighting?

Instead, these abuses should be addressed (when their scale becomes comparable to other kinds of abuses) by identification of indirect characteristics associated with the high likelihood of under-reporting. These characteristics may be the size of the premises, use of some forms of advertisement or brands, industry, etc., or some specific combinations of them. The respective categories should be treated separately – maybe, expelled from Tier 2 (thus, have to use Tier 3 or general system of taxation), maybe forced to install the cash registers – in this case, for good reason; maybe something else. But these complications will not and should not damage the rest 95% of entrepreneurs that did not violate anything.

STS as a privilege

Finally, as mentioned above, the STS is, in a way, a privilege. Although this was not the initial intention of its creators, there is nothing wrong with it, since some kind of privileged regime for micro business can still be partially justified for at least two reasons mentioned above: social (as it helps reduce unemployment) and institutional (as a compromise for de-shadowing). Of course, as with any kind of a privilege, it is unfair, and, more importantly, distorting. But how important are these effects?

According to the same LEV study, the direct fiscal cost of privileging small and micro business with relatively lower rates that the Ukrainian STS provides is 4.8 bln UAH, or 0.3% of GDP. Along with abuses mentioned above (using STS for avoidance of labor taxes) they constitute UAH 11.1 bln, which is about 60% higher than is saved on unnecessary accounting and other administrative and compliance costs. Note, however, that the revenue that is not collected to the budget is still not wasted, as it becomes private income. Meanwhile, on the other scale we have net losses on unnecessary bookkeeping and inspections – so, at this level the STS is quite likely to be welfare-enhancing, in spite of its deficiencies.

However, the distortions it creates may still impose losses that outbalance the gains. An attempt to estimate these losses quantitatively yielded no significant results. A qualitative analysis reveals the fact that at least some of these distortions may drive in a direction that is desirable from other viewpoints. In such cases, they should be considered as elements of a competitiveness policy, social policy, etc.; and therefore the “distortions” should be called “incentives”. So, which are the main distortions, and how to treat them?

Some firms deliberately restrain their growth or artificially split apart in order to avoid exposure to the confiscatory general tax system. This should be considered adverse, however with a reservation that many of these firms will not appear and grow at all unless sheltered from “general” tax system in their infancy. The obvious way to reduce this negative effect is by making the general system more favorable to business. The good news is that unlike in many other cases, this distortion creates political-economic interests in its alleviation. And it is not only a hypothetical benevolent government that is interested. There is a large number of small enterprises that have already overgrown the nursery of the STS by their business models, but still remain reluctant to accept all of the problems of the general tax system. Besides, usage of tax-avoidance schemes described above incurs high risks (such as fraud by the employees) and other internal transaction costs. They largely complicate crediting, selling a business, and are absolutely incompatible with any attempts to raise funds on a stock market. The mid-sized firms that now use these schemes would be sooner or later happy to get rid of them, if the conditions of the general system become more favorable. These categories of business can create political pressure for a genuine tax reform, which is a positive side of this story.

| gains/losses from STS | for business | for budget |

| description | numerical estimate (if available) | numerical estimate (if available) |

| direct effects | ||

| savings on simplified accounting | UAH 7 bln + savings on bribe tax | saving on tax audits and inspections |

| lower tax burden for SMEs | UAH 4.8 bln | unclear due to high elasticity and possible increase in the need for social protection |

| actual employees paid as “entrepreneurs” (including professionals (such as IT) not paying labour taxes in full) | UAH 6.3 bln

keeping professionals within Ukraine |

decreasing unemployment unclear due to high elasticity |

| “tax optimization” for larger businesses, smuggling, other abuses | negative and positive | negative |

| externalities: | ||

| distortions in competition and industrial mix | negative | negative |

| de-shadowing | positive | positive |

| self-employment (lower demand for unemployment benefits) | positive | positive |

| total welfare effect | rather positive | rather positive |

There are also widespread complaints that small firms compete unfairly since they pay less taxes. This may be in many cases true, as the average tax burden for them is, indeed, lower than average all over the economy. However, first of all, there is no indication that they will be paying more if pushed on the general system. Just to remind you that the STS was introduced, among other things, for fiscal reasons – as a presumptive tax that is hard to avoid; and it did lead to a dramatic increase of tax revenues from the respective category of payers. Now according to recent data, presented by the USAID SURE project, an individual entrepreneur using the “general” tax system on average pays to the budget roughly the same as one on the STS.

Then, these problems can be acute only for a few rather small sectors, since the STS taxpayers constitute nearly 1/16 of the whole private sector. Note also that this share does not tend to grow as it should if indeed the respective companies won the competition en masse. These distortions should be compared to the ones tolerated (or even created) by the general tax system, where some crony firms can enjoy de-facto privileges on the “corporate profit tax”, industrialized VAT evasion and fraud, and other kinds of “unfairness”. Moreover, the same firms can abuse the discretional opportunities provided by the general tax system for direct suppression of their competitors with sanctions for alleged tax violations, or by simply raiding their competitors.

At the same time, according to the LEV estimations, without the STS the overall tax burden on a small firm would be, on average, as high as 14% of revenue instead of actual 7.7%. This would kill the majority of small businesses [9], especially given that larger companies enjoy the economy of scale and often significant market power. In light of the latter, some privileging of small enterprises may be justified as they help to maintain competition. For instance, the large retailers’ lobby that loudly complains about “unfair competition” in fact represents a small number of whole-national networks that were accused a few times of price collusion and other anti-competitive practices by the Ukrainian anti-trust authorities. It is quite likely that if they manage to get rid of the STS that helps keeping their smaller competitors afloat, these large companies could easily suppress the competition by initiating massive tax inspections of the small vendors, and enjoy vast market power. Note that such developments will, among other things, aggravate the problem of poverty, since as of now, the poor have an affordable option of buying the necessary goods – maybe less convenient and poorly protected, but instead inexpensive due to fierce competition of not-so-heavily taxed small vendors.

Finally, the STS is accused of providing a privilege for well-paid professionals, such as IT-specialists. This is also partly true, but with important nuances. In addition to the “compromise de-shadowing” mentioned above, another important argument in favor of this arrangement is that from a broader perspective it should be treated as an important element of a competitiveness policy.

But, first of all, an entrepreneur has much better opportunities for concealing income. For instance, a computer guy servicing neighbors can easily remain in the shadow, and only a very modest rate of tax can tempt him to go official. At the same time, for the sake of “fairness”, a self-employed person working at her own risk should not be taxed as high as an employee – merely because the latter enjoys quite generous social protection, her workplace is protected by the law, etc. Besides, an entrepreneur has to spend а substantial portion of her time, efforts and money looking for a customer. These are business costs, while most of them cannot be documented because they are implicit. This is the same with learning and other background work: an employee gets compensated for it, an employer can even send her for vocational training; while an independent professional has to do it at her own expense. And, of course, she works with her own equipment.

The problem is that there is a thin and blurred line between a genuine entrepreneur and an employee with many scales of gray in-between. Take, for instance, an IT-specialist that provides services to individuals: he has to advertise and invest in the equipment, then works with clients and gets paid. He is clearly an entrepreneur. Then, he starts selling the same kinds of services to anybody, including legal entities. Is he still an entrepreneur? Yes of course, but theoretically some of his clients can now treat him as an employee. Then, he starts selling his services to one big client – a legal entity. This is the most doubtful situation, since, on the one hand, he has a contract, but, on the other hand, it is not a labor one. Finally, on the other side of the spectrum, this client hires him permanently. The only way to cope with this problem is to bring the tax rates for employees and self-employed close enough so that the remaining difference more or less exactly compensates for additional risks and costs of self-employment. But this should be done mostly from the upper side, there is no other way around, since otherwise those who now work as an entrepreneur will either go to the shadow (as in the example above), or leave Ukraine.

The latter case is especially important and deserves a special treatment due to its impact on the country’s future. As some other post-Soviet countries, Ukraine has a very peculiar competitiveness position. On the one hand, it is notorious with poor market institutions and other conditions that are comparable to third-World countries, on the other it has inherited a potential for innovations that would have never emerged in such a poor country should it have developed in a normal way. This potential could be realized in a globalized World and secure a possible “Ukrainian miracle”, or it can quickly disappear unless supported in some way.

Indeed, the well-paid professionals that constitute this potential are usually mobile, they know foreign languages (or can easily learn them), and so in a globalized World they can choose the best place to live. Still, despite the low tax rates for well-paid professionals there is no inward migration of them to Ukraine – the opposite happens: the country suffers from brain drain and risks losing the remnants of its competitive advantage as an the innovative economy. The foreigners complaining that their Ukrainian colleagues pay so few direct taxes still do not rush to move to Ukraine. And for a good reason: Ukraine is not the best place for middle-class people, since it is unsafe, insecure, prices for goods and services consumed by the middle class are higher than in many EU countries, not to mention the US; loans are exorbitantly expensive (so a mortgage is as expensive as in developed countries), etc. Low taxes help to at least partly compensate for these deficiencies, so people at least get “value for money”. Therefore, this distortion works in a positive direction by at least partly alleviating brain drain and helping preserve the capacity for innovations.

Just as with the other kinds of abuses or privileges related to the STS, these are insignificant compared to the major ones. According to the latest estimates [10], all of the STS Tier 3 payers that could be potentially accused of using (or abusing) this privilege received for the whole year of 2014 about UAH 24 billion – so, this number should be considered as an overestimated upper limit. But it is still less or equal to the monthly amount of envelope wages paid in Ukraine.

Conclusions

All of this does not mean that simplified taxation needs no reform at all. No doubt, it is not perfect and has much room for improvement – some of these ways were suggested above. However, the general tax system badly needs a much more comprehensive, radical and deep reform. ‘Equal conditions for all’ is not a bad idea. However, as I explained in previous articles, it should be first realized with respect to the general system. As long as the latter is repressive, discretional, unfair and full of really large leakages, there is no point in harmonizing the STS with it – simply because as of now it is much healthier in itself. Instead, wouldn’t it be better to make an opposite harmonization – try to make the general system equally simple in use, straightforward, predictable, corruption-proof, and equal for all?

The next question is “what does ‘equality’ mean in this case?” First and foremost, it means that the rules are applied equally and impersonally to all that are subject to them, without any discretion, bias, or cronyism. In the Ukrainian reality, this means “without any opportunity for discretion”, or, at least, with as few opportunities as possible. But assume we achieve this, and the general tax system is not repressive and discretional any more. Should simplified taxation in any form persist above this point? Yes, although, perhaps, on a somewhat lesser scale.

Above I mentioned that there is at least one natural economic reason for simplified taxation of micro business: it does not, in itself, need bookkeeping sufficient for tax purposes. Thus, there would be no need in simplifying the taxation for the entities that overgrow a certain size (to be defined by research) that requires accounting for purely business purposes. Ideally, this should be done by some positive economic incentives. A universal property tax (based on imputed value) paid by all, including the micro business subject to STS, and combined with (non-discretionary) taxation of redistributed profits only, can largely do the trick. Dramatic lowering or cancellation of the payroll tax along with the PIT can help with another part of the story. But the ceilings for annual turnovers can be still necessary.

Further evolution could involve differentiation of rates and their gradual increase, particularly for some services in Tier 3 that are most frequently abused for tax avoidance. But it should be done very slowly, in order to give the people enough time to adjust, and only after elimination of the really major loopholes in the general system. Any increase in the rates should be done only in light of economic growth.

But these are only very rough and preliminary suggestions. Let me reiterate that a possible reform of the STS can and should be considered only after successful implementation of the “big” tax reform, otherwise it resembles designing a terrace prior to the main building. Nobody can predict right now what new ways of tax optimization the taxpayers will create, how large the abuses will be, and so forth. Yet, there will be enough time to inquire and discuss all of this after the main reform will be implemented. There is no need to rush.

Appendix 1

The “Single tax” for small business was introduced in the late 1990s as an effective measure for preemptive taxation of micro businesses that were otherwise almost fully evading taxes. For some time it was even a sort of “best practice” example. Before its introduction, the small open market vendors normally paid no more than a personal income tax (PIT) on a minimal wage, although during those times their business was quite profitable. Instead, they were inspected almost daily [11] with symbolic official outcomes but, probably, sufficient unofficial “duties” paid to inspectors that otherwise would not be so interested in frequent visits to the bazaars. Introduction of simplified taxation in a form of lump-sum single tax immediately increased tax proceedings from this category of payers a few times [12] (!), meanwhile allowing for rapid growth of small and micro business. Notably at the time, it was supported by the IMF and the World Bank as an effective measure of taxing micro business – along the lines of the “compromise de-shadowing” argument explained above.

It is worth highlighting that the use of the STS was and remains a matter of voluntary choice for the payers. Hence, the taxpayers en masse have voluntary chosen to pay much more in taxes – just unbelievable! However, the answer is simple: perhaps, the cost of compliance and discretionary administration (that, in turn, means uncertainty and a bribe tax) was higher. Thus, in fact this paradox just indirectly partly revealed these hidden costs, and channeled them to public use.

However – now it can be openly said – the true main reason behind the introduction of a single tax was not even its fiscal effect (anyway not critical for the budget revenues), but a political-economic one. Back in the Fall of 1997, Ksenya and Dmitry Lyapin, during this period analysts at the ‘Yednannya’ union of entrepreneurs, told the author in a private discussion that they had an idea on how to push Ukraine towards a liberal market economy and democracy. Namely, they offered to create a payable political-economic demand for opening-up of the new opportunities by liberating three million genuine middle-class people from their instant struggle with misery, on the one hand, and somebody’s personal discretionary rule based on blackmailing, on the other hand. As a tool for this generous task, they proposed simplified taxation in a form of single tax. In less than two years, it was implemented due to the personal efforts of Kseniya Lyapina [13], Alexandra Kuzhel [14] and Yury Yekhanurov [15]. And indeed, by 2004 there were already a few million of such middle-class people that played a critically important role in turning an intra-elite upheaval into a genuine revolution.

Of course, simplified taxation was not without its own problems. Most of all unfortunately, the law did not stipulate any indexation neither for the rates of lump-sum single tax, nor for the upper limits of business revenues for its users, even from the beginning. This soon turned this special regime into a privilege: initially the maximum rate was set well above the average salary, and the minimum one was higher than a PIT on a minimal wage; but in less than five years inflation and wage increases diminished these still fixed amounts in relative terms by many times, and in a few years ultimately made them insignificant comparing to other business expenses. On the one hand, under these privileged conditions small business grew by several times and by 2009 reached the level of one-third of the total official private sector employment, and 66 small business entities per 1000 people – the latter is more than in the most of EU countries. Nevertheless, the quality of this business remained quite low, since the de-facto privileged regime caused lots of low-profitable micro businesses to emerge. Also, a privilege allowed those providers of B2B services that were endowed with significant market power (first of all, the owners of the bazaars) to raise their prices, therefore actually substituting taxes in the composition of business costs of their clients. In full accordance to theory, after 2004, small business became dominated by individual entrepreneurs that could hardly earn an approximate average salary with such fierce competition. Still, they were saved from unemployment or more adverse conditions at the larger enterprises.

What is even worse, is that with any kind of a privilege, the simplified taxation became widely abused (see the main text). These abuses were used in 2010 as an excuse for Yanukoviych-Azarov’s government’s attempt of curtailing and emasculating of simplified taxation supported by some Western advisors [16] claiming for “major abuses” [17] it brings about. However, arguably, the true main reason completely overlooked by these advisers was the political-economic one: Yanukovyich wished to get rid of the middle class that seriously threatened the “Limited Access Order” during the Orange Revolution and those times successfully obstructed him from fraudulent succession of power from Kuchma. Note that the crackdown on simplified taxation was undertaken under the motto publicly revealed by the PM Azarov: “We wish to bring people back to the factories”. If the true reason was indeed fiscal, the arguments should rather be for a substantial increase in the budget revenues, or as an opportunity to decrease taxes for the rest of the economy. Such kinds of arguments were also used, but no assessments of the fiscal effect were ever published. Another plausible reason for some industrial lobbyists (particularly, the ones in light industry) to support curtailing of simplified taxation was elimination of successful competitors and boosting the supply of a cheap labor force. Although, it is also possible that these lobbyists were just politically bribed: the light industry, which representatives were the most active lobbyists against simplified taxation, was eventually privileged with an exemption from the corporate income tax.

This attempt was also accompanied by a dramatic increase in the “social contribution” (payroll) tax that was previously included into a single tax [18]. In 2010, the rule was changed so that the total tax liability rose approximately two times and became unbearable for the smallest individual entrepreneurs [19]. It also increased the barriers for entry or legalization.

Taken together, these two simultaneous changes resulted in disastrous social consequences. First of all, they led to an uprising of small businesses known as the Tax Maidan, when thousands of small entrepreneurs occupied Independence Square in Kyiv. They eventually forced the government to surrender: it had to agree to keep the simplified taxation as such, and started negotiations concerning its reform – so, the government’s initial commitment appeared non-credible. Nevertheless, the new system that eventually emerged as a result of these negotiations in a year was similar and hardly any more favorable for small business than the original one [20], the repressions against entrepreneurs that took place in the process along with above-mentioned drastic raise of the tax rate caused small and micro business to shrink. Most importantly, its main social role – securing employment – was seriously damaged: according to national statistics, about 2 million workplaces were lost in small and micro businesses during 2010-2011 [21]. Most of these probably just moved into the fully unofficial sector. Also, fortunately, the economy during that time was still recovering from the decline of 2009, so Mr. Azarov’s dream has partly came true: a few hundred thousand of the fired employees and entrepreneurs that gave up were probably absorbed by mid-size and large enterprises, as employment there went up.

Previous parts of the article:

The Ukrainian Tax System: Why and How it Should be Reformed. Part I

The Ukrainian Tax System: Why and How It Should Be Reformed? Part II

Notes

[1] О.Бетлій, І.Бураковський, К.Кравчук “СПРОЩЕНА СИСТЕМА ОПОДАТКУВАННЯ В УКРАЇНІ:ОЦІНКА В КОНТЕКСТІ СУЧАСНИХ РЕАЛІЙ“. Look at the paper for methodological cautions and limitations of this study

[2] The current Ukrainian definition of a micro business actually embraces some broader categories of small business for which the above arguments do not hold. Actually, not all entrepreneurs that can be officially qualified as a “micro business” are eligible for the STS too. And even among the later, an entity with annual sales of 20 mln.UAH can hardly be considered as a genuine micro busyness. So, in this section we are talking about very small entities, predominantly sole proprietors or family businesses with at maximum a couple of employees.

[3] compared to 0.07% of the turnover for the companies selling over 35 million UAH annually – all of the data for 2008, the most recent available

[4] In the work this figure is interpreted as a “subsidy”. This may be correct in comparison with other sectors, but on the economic balance sheet it should appear as “savings”, or, rather, avoiding waste.

[5] p.7: ‘Subsistence businesses result mainly from the fact that unemployment benefits in Ukraine are insufficient to cover the living costs’…(p.15): “Subsistence businesses should not exist in a developed or emerging economy. Subsistence businesses can play an important role during the transform process from an undeveloped agricultural stage into an industrial stage. But in an emerged economy like Ukraine’s, it is a sign of system failure that so many of this kind of business exist.”

[6] it is hard to estimate other kinds of abuses due to the lack of data. However, smuggling and related abuses are not the problems of the STS. Splitting is costly for any more or less large firm so the losses are limited. It can be made useless by a good and sufficiently high property tax.

[7] there is plenty of empirical evidence of this fact. Look, for instance, here or there

[8] look at the referred paper for details of assumptions and cautions

[9] Most individual entrepreneurs work in retail. And this is an extremely competitive sector, so a margin of 30% is considered very high for most kinds of goods. It should cover all kinds of costs, including rent for the premises, equipment, and salaries (if applicable). Taking this into account, even the current 4% of the turnover in Tier 3 is often too high (from anecdotal evidences). 14% is nearly half of the trade margin, so it would kill at least the retail – hence, the majority of currently operating small entities.

[10] Made by the author and Olga Bogdanova based on the data obtained from the State Fiscal Service on a special request, unpublished.

[11] Obstacles to Small Business Development in Ukraine. IFC Survey of Small, Private Businesses in Dnipropetrovsk, Lviv, Kharkiv and Vinnitsa (October 1997) – International Finance Corporation Kiev, Ukraine.

[12] A letter of the Tax Administration, available upon a request to author.

[13] later on – the MP, now the Head of the State Regulatory Service.

[14] Those times – the MP, later on – the Head of the State Committee on Entrepreneurship, now the MP.

[15] Those times – , later on – the Head of the State Committee on Entrepreneurship, the MP, the Prime Minister of Ukraine in 2006-2007, then the Minister of Defence, now out of politics.

[16] Although the recommendations of the referred paper were somewhat milder than Azarov’s propositions, they still were aimed at substantial curtailing of simplified taxation. A few quotes: “B2B services … starting 2014 should switch to general taxation. Entrepreneurs’ physical persons – on the simplified should pay at least minimum pension insurance contribution. Probation period for participating in Simplified taxation – 1 year of operation under general taxation (article from the draft Tax code). Retail trade as well as persons providing other B2C services should have cash machines and provide customers with checks”.

[17] “the current system is to be identified as one of the major fiscal problems in Ukraine as of today”

[18] In fact, this increase was geerally justified because the absolute value of social contribution included into the single tax (at maximal rate) remained the same, while minimal salary rose almost ten times. However, it should have been done gradually and during the years of economic boom.

[19] Although this increase was not substantial for wealthier entrepreneurs (as the ones working in the big cities) they were still sensible for the ones in provinces. Besides, although other business costs could be higher than a tax, they did not decrease, so the margin diminished substantially.

[20] A part of the social contribution.

[21] Note that this happened for the first time since the introduction of simplified taxation. Small and micro business grew up, although in a diminishing rates, both in the year of a boom and during the crisis and subsequent decline in 2008-09. Also, such a fall cannot be explained by the alleged elimination of fake sole proprietors registered for the sake of tax avoidance, because (a) a rough estimation of their number was about tens of thousands at maximum – quite a lot, but incomparable to 2 mln., (b) the new system also, alas, allows for such kind of abuses – then, why should they go out of business?

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations