The Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022 brought back the spectre of a nuclear war, WWIII, and other potential horrors. Announcing the attack, Vladimir Putin threatened to launch nuclear missiles at anybody standing in the way. The shattered European – and global – security and Russia’s nuclear blackmail have enormous implications for the world: international treaties seem to have little security value, nobody confronts nuclear powers, smaller countries are particularly vulnerable, and economic dependence on actual or potential aggressors is a critical weakness. The rational response for everybody is to arm as quickly as possible. Because only nuclear weapons can offer a credible deterrence, the proliferation of nuclear weapons seems inevitable. We are facing the prospect of an arms race like never before.

Indeed, we see many pieces in motion already. Pacifist countries like Germany and Japan announced their plans to revamp their military forces. Neutral countries like Sweden and Finland are applying for NATO membership to get protection. The defence industry is booming: the defence stock index jumped by more than 10% from 23 February to 28 February 2022. Many countries and companies are re-evaluating their ties with China and are trying to move their production elsewhere before it is too late. Potential victims feel particularly eerie. For example, Taiwan announced it would be extending its military draft to beef up its defences. All of these carry huge economic costs.

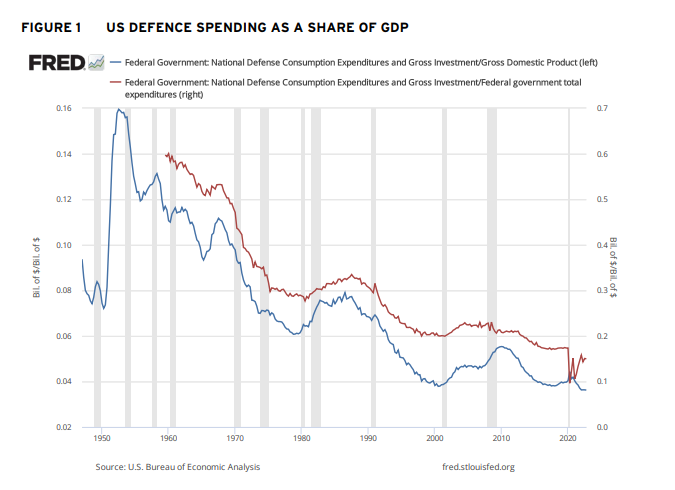

At the height of the Cold War, the US committed 10% of its GDP to military spending (Figure 1). With the current GDP, this amounts to over $2.6 trillion. Every year. In the US alone. It may be hard to comprehend now, but military spending accounted for over a third of federal government spending. This means that instead of building schools, hospitals, etc., the government was building submarines, missiles, etc. Was this due to the lobbying of the military-industrial complex? Maybe, but only partly so because there was no other plausible alternative given the Soviet menace.

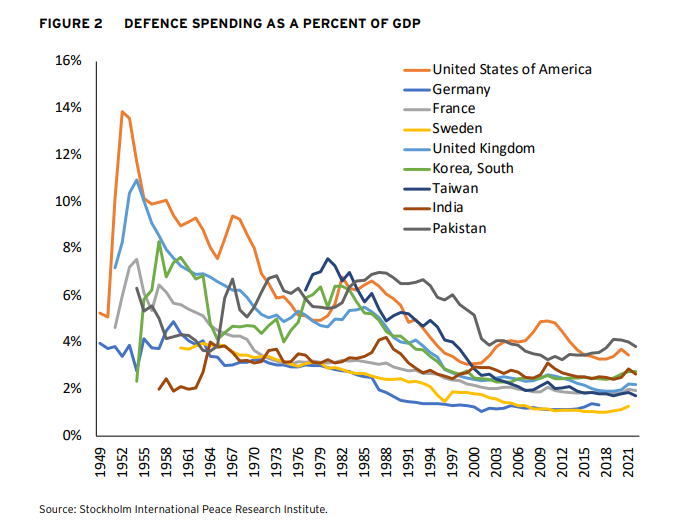

The US carried a disproportionately large burden of defence spending during the Cold War, but other democracies spent fortunes on defense too. According to the estimates of the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, the UK spent 5% of its GDP on defence in 1980. Neutral Sweden was not too far behind with 3%, which was close to France and West Germany. The current generation of Europeans may be shocked to learn that total dollar defence spending in Western Europe was roughly half of US defence spending. Other parts of the world had to be in the arms race too. For example, South Korea and Taiwan spent 7.3% and 6.2%, respectively. Proxy wars in Africa led to more military spending there as well.

The collapse of the Soviet Empire not only reduced war risks but released enormous resources for peaceful uses. Military spending declined everywhere (Figure 2), even in places with unresolved territorial disputes (e.g. India and Pakistan). These newly available funds were called the ‘peace dividend’.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine puts the dividend at risk. For example, after the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014, the Obama administration announced the modernisation of US nuclear weapons. The Congressional Budget Office estimates the cost at $400 billion over the next 30 years, which comes on the top of $800 billion necessary to maintain nuclear forces. With the growing security threats emanating from Russia and elsewhere, one can expect that more dollars will be committed to this and similar programmes. Another round of Cold War appears to be a rather plausible scenario. It seems now that only a miracle can save the world from sliding into an out-of-control arms race.

This miracle has a name: Ukraine

The Ukrainian David has not only depleted the armed forces of the Russian Goliath but also returned some Ukrainian territories occupied by the Russian invaders. The heroism and determination of the Ukrainian people are most inspiring but, of course, Ukraine is not alone. The military and economic aid from Western democracies is helping Ukraine to maintain the war effort. The sums are significant, but they should be put in perspective.

For example, Ukraine needs roughly $45 billion in 2023 to keep its economy running. Undoubtedly, this is a large amount, but it is only 0.1% of the GDP of Ukraine’s allies, 4% of NATO’s annual budget, and 9% of the spending announced so far by European countries on helping consumers with energy costs (Shapoval et al. 2022). And as observed by Jens Stoltenberg, the NATO Secretary General, while the West pays in dollars, Ukraine pays in blood. In other words, the cost of containing Russia is orders of magnitude smaller than what the West would have to shoulder with another Cold (or not-so-cold) War. Furthermore, if (or hopefully when) Ukraine defeats the Russian aggression and initiates changes in Russia that will make future aggression or nuclear threats impossible, future aggressors will think multiple times before invading other countries.

On the other hand, if Russia subdues Ukraine, the law of the jungle will describe international relationships: weak/small countries will be conquered by large/strong countries. The fall of Ukraine will almost certainly invite more aggression. Thinking that the Nazi invasion of Czechoslovakia was a “quarrel in a far away country, between people of whom we know nothing” was a capital mistake that resulted in WWII. Similar thinking about the Russian invasion would be a tragic repeat of history.

This is why rivers of economic and military aid should flow to Ukraine. Only Ukraine’s victory can prevent an unprecedented arms race. No country in Europe or Africa (Fofack 2022) or elsewhere can afford another Cold War. Helping Ukraine is the best investment in global security that can save the peace dividend.

References

Fofack, H (2022), “Africa and the new Cold War: Africa’s development depends on regional ownership of its security”, Brookings Blog, 19 May.

Shapoval, N, J Nell, T Mylovanov, Y Gorodnichenko, O Bilan, and T Becker (2022), “Financing Ukraine’s Victory”, CEPR Policy Insight 118.

#helpUkraine_helptheWorld

This publication is a part of a collection of essays initiated by the National Bank of Ukraine. Famous economists, political scientists and historians, experts recognized in the world, volunteered to share their thoughts and arguments on why helping Ukraine is helping the world. The complete book of essays can be found via the link.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations