Many U.S. cities face an impending investment disaster. Promising plans for development and infrastructure remain on paper because of fiscal constraint. Even the most pressing infrastructure restorations are postponed due to the lack of funding. With the federal government restructuring spending, state governments encumbered and local municipal finances saddled with obligations, public resources available for investments in infrastructure and services are becoming increasingly scarce.

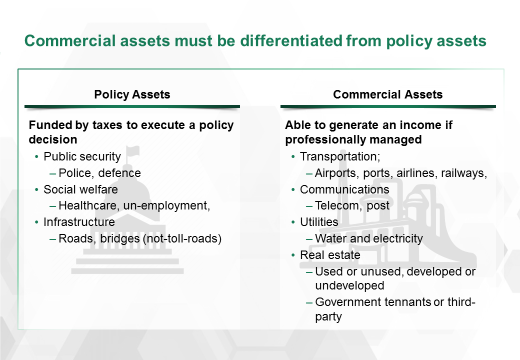

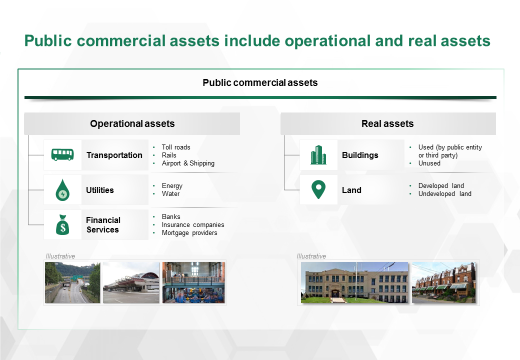

There is way to end this investment shortage. The solution is in the management of the wide range of public commercial assets owned by each city, a tool that has been largely untapped in US cities. Every city possesses a multitude of commercial assets including operational assets like airports, ports, utilities supplying water and electricity, etc., and real estate assets like publicly owned land & buildings. These assets currently represent large sums of foregone earnings because of their underutilization and poor management. This is not about privatizing public assets or pursuing dilutive public private partnerships passing public wealth disproportionately to the private sector.

Achieving a reasonable yield on publicly owned real estate and other commercial assets would free up more resources than most cities’ total current investment in infrastructure, including roads, railroads, bridges, water, electricity, and broadband. In other words, most cities would be able to increase their investments by more than double through wiser use of their commercial assets. Unlocking the value of public assets through improved management is a powerful alternative to spending cuts, increased taxes or further public debt.

A crucial first step is achieving a proper understanding of the city’s balance sheet. With this list of assets in hand, taxpayers, politicians, and investors can better grasp the long-term consequences of political decisions and make choices that increase returns rather than taxes, debt, or austerity.

The idea behind managing public assets more professionally is not about surreptitiously repurposing a museum and library into an amusement center or a City Hall into a bowling alley nor about undue transfer of public wealth to the private sector. Governments’ ownership of vast commercial assets has for the last half century triggered a polarized debate that pits privatization against nationalization. Instead of this misguided debate about the ownership of public assets, we argue for a focus on the quality of their management to support the public agenda and the U.S. economy. It should be noted that the combined wealth of cities held in their public assets is several times larger than that of their national governments, but this wealth remains opaque and largely neglected.

A crucial first step is achieving a proper understanding of the city’s balance sheet. With this list of assets in hand, taxpayers, politicians, and investors can better grasp the long-term consequences of political decisions and make choices that increase returns rather than taxes, debt, or austerity. Efficient management of city assets through our proposed institutional structure – the Urban Wealth Funds- designed to break free from short-term political influence will enable cities to ramp up important resources to fund much needed infrastructure investments.

Public Wealth of Cleveland

Cities generally do not assess the market value of their economic assets, but even a rough calculation can help illustrate the great economic importance held by public assets.

Consider a city like Cleveland, which at first glance does not appear to be particularly wealthy. The city reported a total assets value worth $6 billion in 2014. While this amount exceeds the city’s liabilities, it still largely underestimates the true value of the public assets[1]. Like most U.S. cities, Cleveland reports its assets at book value, valued at historic costs. If reported using the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), which require the use of market value for assets, the assets’ worth would be significantly higher than what is currently reported[2]. Furthermore, due to a legal quirk, many assets acquired before 1980 are not even accounted for. In other words, the city is operating without fully understanding or leveraging its hidden wealth.

If we make the conservative assumption that the price-to-book ratio (the multiple of the market value over the book value in the accounts) is about 5 times, then Cleveland’s assets would be worth US$30 billion, a figure that still does not include the many assets that are unaccounted for. Let us emphasize that we are not claiming Cleveland’s price-to-book ratio is 5—it might be 3 or 7. The point is rather that the Cleveland city administration and political leadership do not know the value of this ratio and are therefore not in a position to fully measure the magnitude of the opportunity cost by leaving these assets undermanaged. If they had the proper visibility, they would get a sense of the urgency to develop these assets shrewdly.

Accounting for the market value is the first step toward quality asset management. The next step is to understand the yield or return that the city earns from revenue and rising market values on its assets. This is key to be able to compare it with other alternative investments, but also to understand whether the performance has been satisfactory, and show stakeholders that their wealth is responsibly cared for.

Accounting for the market value is the first step toward quality asset management. The next step is to understand the yield or return that the city earns from revenue and rising market values on its assets.

By design or by default, Cleveland does not report any return on its assets. Assuming, again very cautiously, that the city could earn a 3 percent yield on its commercial assets with more professional and politically independent management of its assets. A modest yield of 3 percent on a portfolio worth $30 billion would amount to an income of $900 million a year. That is more than Cleveland’s current annual net investments of about $700 million. In other words, even with a modest yield, Cleveland could double its investments.

Cleveland is by no means exceptional. It represents a common scenario across U.S. cities, and in fact internationally, of public wealth trapped in real estate and other commercial assets that are not optimized.

Toward professional asset management in cities

Commercial assets owned by governments are a virtual (and in some cases, literal) goldmine and they extend far beyond the obvious, visible assets like official buildings, the local airport or railway station, or utilities. Underneath this tip of the iceberg is an ecosystem of less visible assets (see box). Many pieces of this vast portfolio—such as buildings for large telephone exchanges and post offices, or just vast spaces for administrative paperwork—predate the arrival of technology that made their purposes obsolete.

There are three steps to create a fund to manage public commercial assets:

- Promote transparency: Compile a list of assets and conduct a indicative valuation of the portfolio of assets that will allow the production of an informal review of the portfolio and the attraction of public support for professionalizing the management of the portfolio.

- Set-up the institution: incorporate the fund, transfer all assets, and appoint a professional board and auditors, so that the government can fully delegate the responsibility and accountability of the management of the portfolio.

- Actively manage assets: Produce a comprehensive business plan for the portfolio as a whole and for each underlying segment, such as real estate and operational assets, to understand how to put each asset to its most productive use, revealing the opportunity cost of using the asset in a sub-optimal way.

Cities that have successfully mapped their real estate will find thousands of assets made visible, far beyond the well known public building. All these assets can be optimized and generate greater value through a more professional management, even stranded assets may be revived with the right approach in place. A return on capital can be achieved through commercialization and optimization, and ultimately through rationalization.

Commercialization requires that a comprehensive business plan makes an assessment of all assets, including those assets that are unused, used by third parties, or directly used in the provision of public services, but that can either be (1) relocated to more cost-effective/beneficial locations, or (2) used to generate ancillary income (e.g., through additional/alternative use of real property and exploitation of publicly owned intellectual property).

Optimization requires economies of scale to be achieved across the entire portfolio and should be as much of a priority as maximization of yield from each individual asset.

Rationalization involves determining mature assets, which are those that have reached a fair value and where the proceeds from a sale can be reinvested in assets that are capable of yielding a higher return. Mature assets could be disposed of at the relevant point in the market’s cycle, as part of the broader business plan for maximization of yield across the entire portfolio. Monies generated from rationalization activities should be first made available as a source of funding for achievement of the business plan and ultimately to fund infrastructure investments.

Rationalization involves determining mature assets, which are those that have reached a fair value and where the proceeds from a sale can be reinvested in assets that are capable of yielding a higher return.

Even common public buildings can sometimes find ways to improve value for all stakeholders involved. Consider the example of a school located in the city business district, where land has extremely high market value. This land is being used for an activity that, though socially important, could be located a couple of blocks away on much cheaper land—perhaps to the benefit of the students’ learning—and this relocation would release the land occupied by the school for use with the highest market value. Such a change would no doubt be welfare-improving because it would raise city income while giving the government the possibility to build an equivalent or better school with the revenue from developing the more valuable property. This model has been successfully rolled-out by Hamburg Hafen city fund that has developed several education facilities such as Katharinen primary school & HCU HafenCity University.

Such opportunities abound, but are often not taken advantage of because the political and administrative institutions overseeing the assets are not geared towards exploring avenues to generate greater value. Achieving successful outcomes requires these activities to be shielded from political influence.

Unlocking value—international examples

A few cities or city-states have been very successful in setting up independent and professional holding companies and Urban Wealth Funds to manage their commercial wealth and help funding infrastructure investments.

Hong Kong

Hong Kong’s fast growing economy prompted a study released in 1967 that suggested formation of a public transport company. This led to creation of the MTR Corporation (originally, Mass Transit Railway Corporation), established in 1975. The corporation is a sector focused urban wealth fund managing an integrated rail transit system that owns rail infrastructure, the adjacent land, as well as much of the real estate. It runs the subway and rail system in Hong Kong. Although listed on the local stock market in 2000, the government remains the majority shareholder. MTR operates a predominantly rail-based transportation system comprising domestic and cross-border services, a dedicated high-speed airport express railway, and a light rail system.

MTR has funded and managed vast infrastructure investments and is also a major property developer that helped to significantly increase the delivery of new residential homes in Hong Kong. Many of its stations are incorporated into large housing estates or shopping complexes. Residential and commercial projects have been built above existing stations and along new line extensions. So far it has successfully developed the property over about half of the system’s eighty-seven stations, amounting to 13 million square meters of floor area. New projects being planned or developed will add another 3.5 million square meters.

MTR pays a substantial dividend to the city, providing an income for the government that has been deployed to pay off existing debt and develop other assets[3].

Copenhagen

Copenhagen’s By og Havn I/S (City & Port) is another sector urban wealth fund established by the city of Copenhagen in 2007, with 5 percent participation from the national government, to develop a number of specific urban districts. It is the the largest UWF and urban development project in Europe, with a total area of 520 hectares and the result of a number of mergers of several development companies and real estate assets owned by the local and national government. This includes water front districts in the Copenhagen harbor area totaling 210 hectares, as well as the land locked Örestad-district of some 310 hectares between the city center and Copenhagen Kastrup airport.

The successful development of these districts will enable the company to contribute more than 33 thousand new residential housing units, 100 thousand work spaces and a new university for more than 20 thousand students, as well as new parks, retail and cultural facilities.

With the financial surplus from its operations, City & Port has been able to help fund part of the extension of the local metro system as well as other infrastructure investments required by the developments and the city. It does this through a direct dividend as well as with investments in the various projects.

London

London Continental Railways Limited (LCR) was originally set up in 1994 as a holding company for the European Passenger Services to build the Channel Tunnel Rail Link from London to Paris. Having divested itself of the actual rail link, the company’s is now an segmental UWF with a primary focus on property development and land regeneration, such as the area around King’s Cross Station in London.

The decision in 1996 to move the Channel Tunnel Rail Link, connecting Paris and London, from Waterloo to the St. Pancras railway station, next door to King’s Cross, became the catalyst for change. It prompted the UK government to develop the King’s Cross site through an independent holding company, with Argent, a UK property developer, acting as the partnership’s asset manager.

King’s Cross has always played a vital role in the commercial life of the capital. The 27 hectare development has a total of 8 million square feet of gross floor space of mixed-use development, including 3 million square feet of new workspace; about 500 thousand square feet of retail, cafés, bars, restaurants, and leisure facilities; up to 2 thousand new homes; a new university; and a range of educational, hotel, and cultural facilities.

Many of the old Victorian buildings around the site, including the Great Northern Hotel, have been refurbished and reopened. Organizations such as Google, Louis Vuitton, Universal Music, Havas, and the University of the Arts London have chosen to locate here. New public squares, gardens, and parks have opened, as well as restaurants, shops, and cafés. By 2020 up to 50,000 people will be studying, living, and working in King’s Cross. In 2015, LCR sold its 36.5 percent shares to AustralianSuper for the equivalent of $400 million.

LCR’s has other development projects including the $2.6 billion International Quarter project in Stratford, centered on Stratford Regional and International Railway Stations in East London.

The importance of transparency and independence in the Urban Wealth Fund

The best way for a government to manage commercial assets is to put them into a commercial holding company, an Urban Wealth Fund, and allow it to act professionally as if it were a publicly owned private equity fund. The fund would be managed at arm’s length from short-term political influence in a transparent, accountable manner using the relevant private-sector accounting and management practices. These financial vehicles are a perfect compromise: they keep public assets under government ownership while simultaneously preventing undue short-term political interference. The government appoints the auditors responsible for the portfolio and decides on the dividend target and the list of assets that could eventually be sold when sufficiently developed but has no influence over how the fund itself is managed. This strict separation is the key to improved asset management.

Separating the management of commercial assets from the short-term political cycle fulfills at least two important objectives.

The best way for a government to manage commercial assets is to put them into a commercial holding company, an Urban Wealth Fund, and allow it to act professionally as if it were a publicly owned private equity fund. The fund would be managed at arm’s length from short-term political influence in a transparent, accountable manner using the relevant private-sector accounting and management practices.

First, the Urban Wealth Fund allows the government to solve the issue of its inherent inability to take on commercial risk without having to resort to outsourcing transactions, privatizations or Public Private Partnership (PPPs) structures, many of which turn out to be suboptimal for taxpayers as illustrated by Chicago’s unfortunate parking meters privatization deal. In each of the PPP and the privatization models, the private sector is agreeing to finance an asset and take on the commercial risk tied to managing it. In exchange, private actors require a high premium- a cost that will be borne by the taxpayers or the users. By the nature of its set-up, the Urban Wealth Fund relieves the government from bearing the burden of commercial risk while keeping the assets under public ownership.

Second, the ability to use a proper balance sheet allows for much closer alignment of the life cycle of the assets with the management of the investments. The initial costs of an asset, such as design and construction, are usually only a fraction of the total cost over its entire life, with the main costs consisting in maintenance and operations. As such, unlocking public assets’ value requires adopting an investment perspective that extends way beyond a political cycle in order to ensure proper asset optimization. When the political calendar interferes, spending on assets maintenance competes with spending on education, healthcare and other social investments that are systematically prioritized, as they are more popular among voters. Spending valuable taxpayer money on maintenance of assets can be politically risky—unless there is a balance sheet in a separate institutional set-up –a UWF proving the money used has increased net wealth.

There is great value in creating awareness about the very fact that the city owns a whole range of commercial assets that are not visible. As such, a crucial first step would be to publish a lighter version of transparency in the shape of an annual review, an unaudited brochure highlighting the total value and yield of the entire portfolio of commercial assets[4]. The newfound awareness would then set the grounds for a discussion around the establishment of the Urban Wealth Fund.

Our proposals extend beyond the governance of just commercial assets. An Urban Wealth Fund with sufficient independence from governmental control could be permitted to rebalance its portfolio and not only help finance infrastructure investments but also act as the professional steward and anchor investor in newly formed infrastructure consortia. This could turn an Urban Wealth Fund into a great boon to investment in much-needed infrastructure.

Notes

[1] City of Cleveland, Comprehensive Financial Report 2014.

[2] IFRS requires market value for financial instruments and realisable non-current assets, but not for plant, machinery and equipment.

[3] McKinsey Company, “The ‘Rail Plus Property’ Model: Hong Kong’s Successful Self-Financing Formula,” June 2016.

[4] The Lithuanian Government Annual Review of Commercial Assets could serve as an example.

Main photo: depositphotos.com / londondeposit

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations