On March 11, 2015 the IMF Executive Board approved a four-year Extended Arrangement under the Extended Fund Facility (EFF) of about $17.5 billion for Ukraine. The success of the program will depend on the Ukraine’s government long-term commitment to reforms. A good example of how participation in IMF programs coupled with government commitment to reforms can lead to economic revival is provided by India’s experience in the 1990s. In 1991 India went through a balance of payment crisis, where foreign reserves of the country dwindled to two weeks imports, currency values collapsed, and the government was on the verge of defaulting. Participation in the IMF program and a series of structural reforms followed sparking India’s annual GDP growth rate to an average of 6% since then.

VoxUkraine.org specially for “Ukrainska Pravda“

On March 11, 2015 the IMF Executive Board approved a four-year Extended Arrangement under the Extended Fund Facility (EFF) of about $17.5 billion for Ukraine. Majority of analysts welcome the move, noting that it helps Ukraine to avoid immediate financial meltdown. Some, however, point out that IMF conditions might be too harsh and counter-productive. The Ukrainian public’s views are mixed, too.

The arguments in favor of cooperation with the IMF are as follows.

- Ukraine needs money desperately. In 2015 alone it will need 21.4 billion USD to avert financial meltdown, to restore the National Bank reserves, and to stabilize its financial sector. Participation in the IMF program provides some funds to this end. In addition, it may signal to other donors that Ukraine is on the right track and help bring additional financial support to the country.

- Ukraine urgently requires structural reforms. For multiple reasons, the government and the parliament are incapable of meaningful reforms unless there is external pressure from the IMF.

- The conditions of the IMF are draconian. They require monetary discipline and fiscal restraint. These are in the long-term interest of the Ukrainian public and the Ukrainian economy.

The anti-IMF public sentiment rests on the following arguments.

- The loan will have to be repaid, at interest. Ukraine cannot afford to borrow.

- The loan will be stolen by the corrupt political establishment. Taxpayers will have to pay it back.

- Ukraine is a sovereign country. Accepting IMF terms is humiliating. No foreign organization should dictate which laws and policies should and should not be adopted.

- The conditions of the IMF are draconian. They require monetary discipline and fiscal restraint. These are not in the interest of the Ukrainian public and the Ukrainian economy.

We argue that the benefits of Ukraine’s participation in the IMF program outweigh the costs. The adjustments prescribed by the IMF will be painful, but they are necessary to put Ukraine on the path of economic recovery. Two factors will soften the pain:

- first, the IMF program contains some provisions for the social nets that will help those most affected by the adjustments;

- second, economic conditions in Ukraine right now are particularly conducive to the с demands and may soften some of the negative effects.

At the same time we emphasize that participation in the IMF program by itself is not enough to turn things around. The IMF program provides a nudge in the right direction and a way for the government to temporarily commit to reforms. The success of the program, however, will depend on the Ukraine’s government long-term commitment to reforms and its ability to convince the public and investors of such commitment.

The IMF program is front-loaded with $10 billion to be disbursed within 2015 ($5 billion were received by Ukraine on March 13). The rest of the funds will come over the remainder of the program, subject to the successful implementation of the program. T. The important part here is that even the next tranche of $5 billion later this year is not guaranteed, unless the IMF will find the Ukrainian government in compliance. Thus, the IMF will continue to exert pressure on the Ukrainian government to reform the economy by holding the right to withdraw future support.

What does the IMF want? There are two groups of demands:

- Emergency adjustment policies: stabilizing the foreign exchange market; disciplining public finances; repairing the banking system; reforming the energy sector.

- Structural adjustment policies: anti-corruption and judicial reforms; deregulation and tax reforms; and reforms of state-owned companies.

So far so good. The problem – the emergency adjustment policies are going to be painful for the public. Yet, they are needed if Ukraine is to avert even deeper economic crisis. This pain for the public is plausibly the reason why the Ukrainian leadership has been sluggish with undertaking structural changes and seems incapable of bold moves without external pressure from the IMF.

On the monetary policy side, the objective is to stabilize the exchange rate and curb inflation. The prescribed policies are non-controversial and are likely to have the desired consequences if implemented properly and in a timely fashion. Specifically,

- Ukrainian hryvnia will be stabilized by setting very tight monetary policy targets, including negative real money supply growth. In plain language – no more excuses for money printing for the Ukrainian government.

- Moreover, the largest share of the IMF loan will go towards rebuilding international reserves of the National Bank. Without reserves the National Bank is unable to effectively intervene and maintain the exchange rate. Furthermore, lack of reserves encourage speculative attacks by those who stand to gain from hryvnia devaluation.

- Hryvnia is projected to remain at the level of 23-24 hryvnias per USD on average through 2020. Stable currency is expected to promote exports; tackle inflationary pressure from imports; reduce defaults on loans issued in dollars and decrease probability of bankruptcies in the financial sector.

- Coupled with a requirement that the NBU set its main policy rate (discount rate) with a 12-18 months forward horizon, these policies will increase transparency and help bring down inflationary expectations. Over time this should lower inflation to single digits.

- The IMF also requires greater NBU independence and a gradual switch to inflation targeting framework which has proven to work well for small open economies. Independence of the National Bank is a crucial problem in Ukraine. The National Bank of Ukraine has been forced to indirectly cover the deficit of the gas state monopoly Naftogaz. This lead to pressure on the reserves, culminating in inflationary and exchange rate problems.

On the fiscal policy side, the IMF program prescribes fiscal restraint, with the adjustments mainly coming from a reduction in expenditures, and only minor increases in taxes.

- The IMF target is to improve the primary balance (which excludes interest payments) of the combined general government and Naftogaz from a deficit of 6.9 percent of GDP in 2014 to a surplus of 1.2 percent of GDP in 2016 and a stable surplus of 1.6 percent of GDP from 2017 onwards. Most of this adjustment is expected to happen from a dramatic reduction in Naftogaz deficits from -5.7 percent of GDP in 2014 to a balanced budget from 2017 onwards.

- Eliminating Naftogas deficits will be mainly achieved by increasing tariffs. It is prescribed that retail gas prices to households will rise by 284 percent on average, effective April 1, 2015. The resulting prices will be more in line with their market values. The savings of the general government will come primarily from lower government spending, but temporary measures to increase tax revenues are also to be used in 2015. The decrease in expenditures will be achieved by delaying pension indexation to December of 2015, effectively freezing them for most of the year (savings of 2.3% of GDP); reducing subsidies to state-owned enterprises (savings of 1.1% of GDP); and maintaining the nominal wage bill of government employees at 2014 level (except military personnel) (savings of 0.8% of GDP).

- The spending cuts together with a jump in utility tariffs are going to be painful, especially for poorer households and retirees. To protect them the program budgets an increase in energy subsidies to households equal to 0.3% of GDP in 2015, bringing social programs expenditures to 4.1% of GDP in 2015 and 4% of GDP in the subsequent years. The program also budgets an increase in government outlays on capital investment of 1.2% of GDP, which would mainly fund immediate reconstruction needs. These steps are not much but might take the edge off the bitter taste of the proposed austerity.

There is no question that fiscal restraint is painful. There is also widespread consensus that reducing debt has important long-term benefits.

But what are its effects on economic activity in the short-run? One school of thought – the conventional Keynesian wisdom – argues that reducing government spending or increasing taxes will lead to economic contraction in the short-term.

An alternative view is that a fiscal restraint can prop up economic activity even in the short-run. There are several channels through which this can occur.

- Lower government spending may mean less taxes in the future, leading to more spending by the public (the consumers, households).

- A fiscal consolidation today implies less need for a larger more painful fiscal adjustment in the future (Blanchard 1990, Bertola and Drazen (1993)). If the government convinces the public that it is now in control of the economy, the public will become more optimistic about the future. The consumers will spend more and the business confidence will improve.

- A fiscal consolidation reduces the default risk of the government and lowers interest rates in the economy for both the government and the private sector (Corsetti et al (2012)). This can increase economic activity.

There is some empirical evidence in support of the non-Keynesian view. A recent IMF study (WEO 2010) finds that fiscal consolidations tend to be “contractionary” but the negative effects are cushioned when accompanied by lower interest rates; a decline (depreciation) in the real value of domestic currency; and when consolidations rely on spending cuts, rather than tax increases. Among the different categories of spending cuts, cuts to government transfers tend to have least contractionary effects, followed by cuts to government consumption, and government investment. Moreover, the contractionary effects tend to be smaller in countries that have high preceding risk of default.

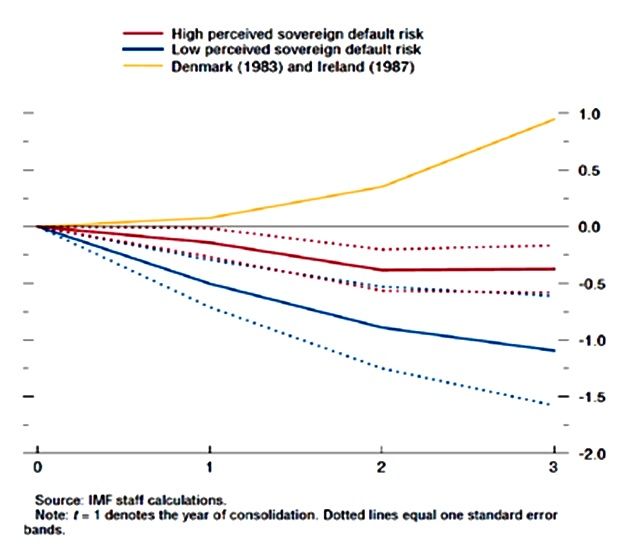

Figure 1 provides some evidence in support of this by plotting the impact on GDP of a 1 percent fiscal consolidation as a share of GDP for different countries. Denmark (1983) and Ireland (1987) experienced sharp deteriorations in their sovereign debt ratings due to large fiscal deficits and rapid debt accumulation. They undertook sharp fiscal consolidations of around 3% of GDP to correct the situation. The figure shows that these fiscal adjustments had “expansionary” consequences. It also shows that countries whose perceived sovereign default risk was high experienced a much smaller fall in GDP relative to countries with a low perceived default risk.

Figure 1. Estimated impact on GDP of a 1% of GDP fiscal consolidation

Can Ukraine repeat the experience of Denmark and Ireland? It certainly satisfies the preconditions discussed above. Ukraine’s interest rates are expected to decline as fears of default subside; the real exchange rate is expected to depreciate by another 17 percent in 2015; and the majority of fiscal consolidation will be accomplished by lowering the social transfers components of government expenditures. A lot will however depend on the government’s commitment to reforms and investor’s perception of this commitment.

One may argue that participation in the IMF program will itself be enough to promote growth. That, however, is unlikely. In fact, empirical evidence suggests that participation in the IMF programs is often associated with negative growth outcomes, both in the short-run and over longer run horizons. This correlation however is polluted by a number of identification issues: (i) countries that are performing poorly are more likely to turn to the IMF for help, making it difficult to distinguish the causal effect of IMF program participation; (ii) governments differ in their commitment to reforms. The countries that are committed to reforms are less likely to apply to the IMF programs. As a result, countries that participate in the IMF programs tend to be those with less committed governments, and are thus less likely to implement reforms and promote economic growth; (iii) difficulty in measuring the degree of compliance with the IMF conditionality.

Existing studies have used different methodologies to account for these problems. Earlier work has shown that the negative correlation between IMF program participation and economic growth survives even after controlling for selection (Przeworski and Vreeland, 2000), but greater compliance with the conditionality tends to weaken this effect. More recent studies (Bas and Stone, 2014) have shown that on average countries benefit from participation in the IMF program.

A good example of how participation in IMF programs coupled with government commitment to reforms can lead to economic revival is provided by India’s experience in the 1990s. In 1991 India went through a balance of payment crisis, where foreign reserves of the country dwindled to two weeks imports, currency values collapsed, and the government was on the verge of defaulting. The government turned for help to the IMF securing a loan on the condition of participating in the IMF program. A series of structural reforms followed sparking India’s annual GDP growth rate to an average of 6% since then.

To conclude, the success of the IMF program in Ukraine depends on Ukraine itself. The participation in the IMF program provides a push in the right direction and a temporary commitment device. While the required adjustments will be painful, there is a number of pre-conditions that will soften the pain. The key to success however is government’s commitment to implementing very needed though unpopular policies right now, and a deep structural reform of the economy in the nearest future.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations