Societal demand for better courts continues to be strong. What are the implications of the dramatic political changes of the last nine months—the exit of Yanukovych from Ukrainian politics, the collapse of the Party of Regions, and the elections of a new president and a new parliament—for the judiciary?

The plausible alternatives are:

- Bona fide judicial reform aimed at cutting ties—parasitic or symbiotic—between judicial elites and political incumbents and creating the institutional and cadre foundation for a judiciary that is both politically independent and clean;

- The replacement of judicial elites close to Yanukovych with judicial elites close to Poroshenko and the continuation of the symbiotic/parasitic relationship between the two branches.

- The conversion of Yanukovych-era judicial elites into Poroshenko supporters and the continuation of the close relationship between the two branches. This option would entail pledges of allegiance from the old judicial elites to the new incumbent.

- Digging-in by Yanukovych-era judicial elites, who aim to transform the judiciary into a politically independent, but still corrupt institution. Then they could reap the benefits of corruption rents without also catering to politicians’ preferences.

On balance, the main events in judicial affairs since February, 2014 point to the last scenario. Yanukovych-era judicial elites have so far actively resisted attempts to be purged and have refused to bow down to the new government. Only a few judges have left the bench voluntarily: 167 (2%), including those due for retirement. At the lowest rung of the judicial hierarchy, district court chairs have effectively ridden out the wave unleashed by the April judicial lustration law. The law summarily fired all chairs and their deputies and mandated that judges in all courts elect new chairs.

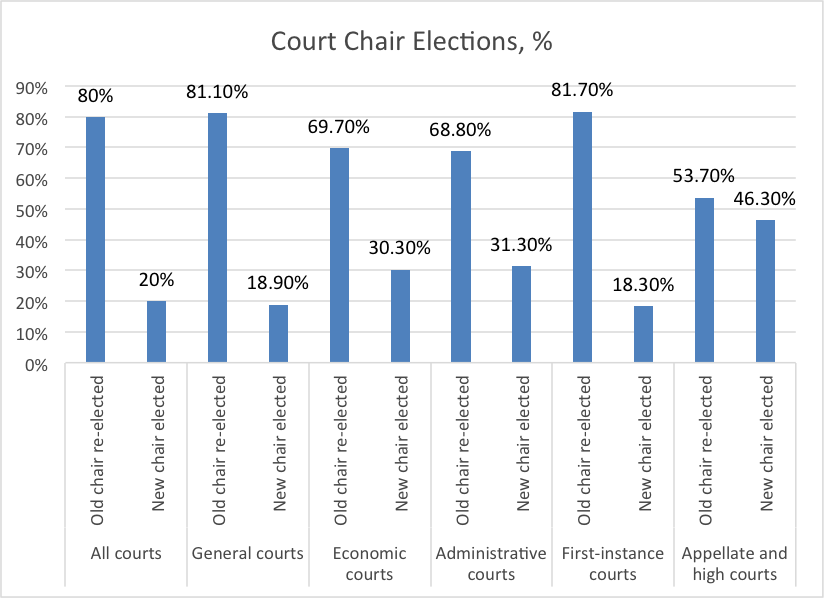

However, after the overwhelming majority (98%) of courts held elections for new chairs, media reported anecdotally that over 80% of elections resulted in the re-election of the Yanukovych-appointed chair. With the help of a couple of research assistants in Ukraine, we have tracked down the complete information on court chair elections that have taken place since April. The results confirm the anecdotal evidence– over 80% of Yanukovych appointees were re-elected; over half of them ran unopposed. Interestingly enough, there are no differences in re-election rates between regions– the re-election rate is the same in the Lviv and in the government-controlled areas of Donbas. We do not observe intransigence of elites in Donbas or the rest of southeast, we observe uniformly strong judicial elites that can withstand political pressure. Notably, there are differences among court hierarchies and court levels. Courts of general jurisdiction have slightly higher re-election rates than administrative and economic courts. Lower courts have higher re-election rates than appellate and high courts. Those differences are not statistically significant, however.

Continuity outweighs change at the judicial governance institutions as well. Even though the judicial lustration law envisioned the immediate disbanding of the High Qualification Commission for Judges (HQCJ) and banned the re-election of anyone who had served on it, the HQCJ continued operating with its Yanukovych-era membership for months. Some legal wrangling has resulted in some turnover, but full compliance with the lustration law has not been achieved to this day. The HQCJ continues to function in its Yanukovych-era composition.

Moreover, the HJQC does not appear to be currying favor with the new political incumbents. It has started receiving referrals for disciplinary action from the Temporary Special Commission set up under the judicial lustration law to identify judges who violated citizens’ rights during Euromaidan and has so far been lenient on the judges. It has so far punished 3 judges with a 2-month suspension. The other judicial governance organ, the High Council of Justice (HCJ), has become a veritable battlefield for influence between Yanukovych-era judicial elites and potential newcomers. Finally, at the apex of the judicial hierarchy, the Constitutional Court also continues to be dominated by Yanukovych-era appointees (for more discussion, see here).

Ukraine’s judicial reform prospects in comparative perspective

The discussion of judicial and general lustration in Ukraine is permeated by comparisons with Central European countries and their experience with lustration in the early 1990s. However, these comparisons are misguided, because both the goals and methods of Central European lustration were different. Central European lustration policies were mainly about exposing truth, rather than about punishing individuals. They were guided primarily by normative concerns—many believed that building a democratic regime based solidly on the rights of participation and contestation was not possible without exposing as fully as possibly the transgressions of the old regime against its citizens’ rights. The goal of rooting out the corrupt networks of the previous regime, which seems dominant in the Ukrainian context, was largely absent from Central European discussions of lustration. Central European lustration policies focused on identifying secret police informers within the civil service and among candidates for elected office. There was no targeted effort to lustrate the judiciary. If the judiciary was at all affected by lustration policies, it was as a result of casting a very wide net.

Georgia and the corrupt and competitive democracies in the Balkans provide a better context for comparison. In Georgia and in Serbia, as in Ukraine, the goal of lustration efforts after the fall of the Shevardnadze and Milosevic regimes was dismantling the networks of the previous regime. In both countries, the judiciary was purposefully and forcefully targeted for reform. The new governments instituted re-attestation processes for judges that led to significant turnover on the bench. The outcomes of those reforms differ considerably, however, and suggest that Ukraine is at a fork in the road.

In Georgia, Saakashvili was successful in sustaining initial judicial reform efforts and replacing the majority of former judges. Georgia has seen significant reduction of judicial corruption as part of an overall trend towards controlling corruption. According to the World Justice Project, for example, Georgia is a leader in the post-Communist world when it comes to curbing corruption (source). However, it appears that the Georgian judiciary has remained politically dependent from incumbent politicians—prosecutions of opposition figures, which many perceive to be politically-motivated, took place under Saakashvili’s tenure and continue under Ivanishvili’s government.

In Serbia, the democratic opposition to Milosevic attempted to purge the judiciary, but ultimately failed because the judiciary actively and effectively resisted. Judges sabotaged the judicial reform process each step of the way. Eventually the governing coalition broke apart and many of the purged judges returned to the bench after challenging their dismissals in court. Over time, the Serbian judiciary has developed political independence from incumbents. Judicial corruption, however, remains a serious concern in Serbia. According to World Justice Project data, 60% of judges and magistrates in Serbia are corrupt. Growing judicial independence from incumbent politicians and bouts of intense judicial-executive confrontation, combined with sustained levels of judicial corruption and rock-bottom levels of popular legitimacy also characterize judicial-executive relations in other Balkan democracies– Macedonia, Croatia, Bulgaria and Romania. It seems that this development route is more common among new democracies than the Georgian experience.

On the one hand, the dogged survival of Yanukovych-era judicial elites bodes well for the emergence of a judiciary that is independent from political incumbents. On the other hand, the retention and retrenchment of compromised judicial elites does not bode well for the Ukrainian judiciary’s popular legitimacy. It is also unlikely that greater independence from politicians would translate in any gains in the fight against corruption. Rather, the entrenchment of judicial elites behind a fortress of institutional independence may sustain current levels of judicial corruption. In any case, it is too early to tell whether the Yanukovych-era judicial elites will indeed manage to retain and consolidate their grip on the judiciary. It is also plausible that the new parliamentary majority will successfully purge the judiciary. What is much clearer is that Ukraine is at a critical juncture in its rule of law development.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations