As a part of social welfare verification, the Ministry of Finance was able to gain access to and audit only 70 percent of the total amount of social payments and 22 million of welfare recipients. The scale of potential misuse is overwhelming — over 500,000 violations totaling to more than five billion hryvnias: pensions for “ghost recipients”, payments to “lost passports”, subsidies for people who are far from being poor, as well as financial aid for fake IDPs who still prefer to reside in the occupied territories of Donbass. And the list is far from complete. Why are chances slim that hundreds of thousands of violations will be curtailed?

Last December, the Ministry of Finance set a course for verification — that is, a complete audit of social expenditures. The step was spurred by a suspicion that a significant part of social benefits comes to recipients not entitled to them. In the process of budgeting for 2016, the Ministry has planned that the verification would save 5 billion hryvnias.

VoxUkraine gained insights into how the Ministry had gone through the verification procedure, where it found over half a million of potential infringers, what aspects of the audit governmental agencies refused to provide information for, and whether it was realistic to save the five billion hryvnias.

Field of Action

Social expenditures are the largest item of Ukrainian national budget. According to the Ministry of Finance, 40 percent of all public funds (at all levels) are spent on welfare benefits. Welfare payments take up as much as 16.5 percent of Ukrainian GDP projected to be around 2.2 trillion hryvnias, i.e. UAH 363 billion.

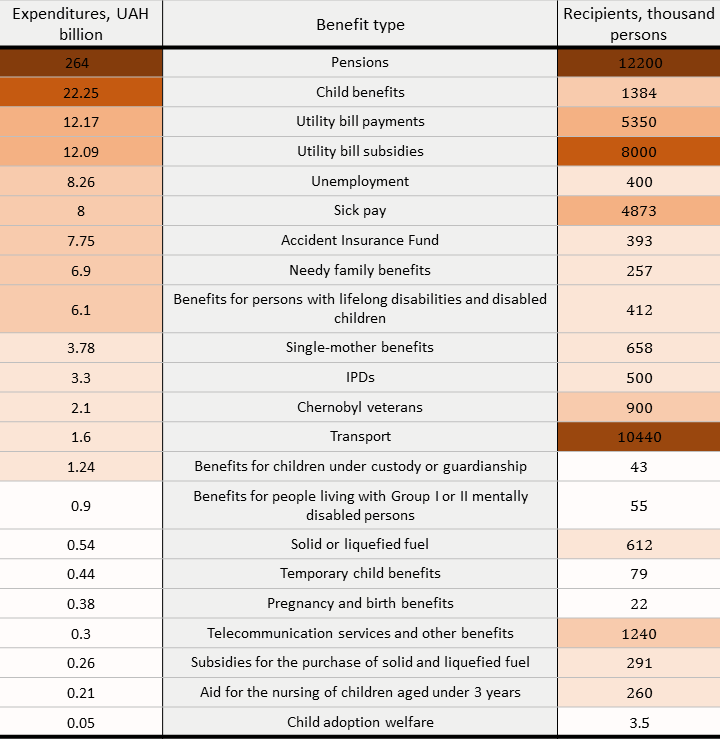

Official statistics shows that most of the budgeted welfare allocations are spent on pensions. According to the Ministry, there are 12.2 million pensioners in Ukraine, which account for 264 billion hryvnias in pension payments or 72.6 percent of total welfare benefits.

The second largest budget item is child benefits. Last year, 1.384 million persons received such payments. The government spent 22.2 billion hryvnias on them, which is 6.2 percent of total social expenditures.

The third largest expenditure item is utility bill subsidies. In 2015, the Ministry budgeted 12.2 billion hryvnias on them, i.e. 3.4 percent of total social payments.

The problem is not the amounts per se, but rather the absence of effective procedures to control the distribution of social benefits. Not surprisingly, this gives rise to corruption scandals involving the management of social welfare agencies. A telling example is a news that the State Employment Service chief has been caught taking a bribe of UAH 500,000. Media sources also regularly report that by no means all Ukrainians get social benefits legitimately.

The verification is intended to eliminate all illegal schemes and save at least five billion hryvnias for the budget. The Ministry of Finance has aggressively pursued the verification process for three months. The first results are already available.

According to official data, the welfare payments that were audited amount to UAH 363.5 billion.

Payment types that have been verified are as follows:

- benefits for internally displaced persons:

- benefits for Chernobyl cleanup veterans

- pensions;

- payments to needy families;

- payments to households with children;

- payments to disabled persons;

- housing subventions for the families of servicemen killed or disabled as a result of ATO.

- annual one-time welfare assistance for war veterans;

- sanatorium treatment for certain categories of citizens.

As of June 1, 2016, 71 percent of total welfare amounts were verified. Information about 22.1 million unique recipients was obtained from various sources.

At the moment, most risks pertain to the payment of utility subsidies by regional state administrations — the Finance Ministry considers 266,259 such payment decisions suspicious.

The Ministry of Social Policy ranks second among public resource managers found in breach of welfare payments. The Ministry of Finance is challenging the legitimacy of 116,791 its payments.

The State Employment Service, which is subordinate to the Ministry of Social Policy, ranks third with 81,014 payment violations.

A very honest Ukrainian

The Social Inspectorate appears to be the only Ukrainian governmental agency that has checked 40 percent of the public money for misuse. The agency’s employees were obliged to visit welfare recipients to make sure they really needed help.

Over the last years, the social inspectors reported that 0.9 percent of payments were suspended, on average. More specifically, the share of fraud was 0.1 percent in welfare expenditures for subsidies and payments to needy families, and 0.2 percent in single mother benefits. These figures do not necessarily mean these payments are free of fraud. More likely, they indicate the lack of an effective mechanism to discover misuse.

The Social Inspectorate was subordinate to the Ministry of Social Policy — a welfare allocation unit meant to be audited by the Inspectorate. A scenario when a subordinate body audits its superior authority predictably failed.

Unfair neighbors

Social welfare audits vary from country to country. In some cases, they were conducted by agencies subordinate to the counterparts of Ukraine’s Ministry of Social Policy. In other cases, special governmental bodies were created.

Great Britain and the USA

Even in developed countries, the figures of misuse were a lot higher than that revealed in Ukraine. For example, the share of fraud recorded during social welfare audit in the United Kingdom and the USA in 2004–2005 was 5.3 percent and 5.07 percent respectively. In Great Britain, social payments are verified by the Department of Work and Pensions. In 2013–2014, £1.4 billion was overpaid due to fraud and errors in housing benefits only (40 percent of total benefits), the agency states.The figures are a lot higher in developing countries. For example in India, 31.6 percent of housing and 53.5 percent of loan programs were implemented with violations in 2003.

Georgia

In the late 1990s, Georgia faced fraud connected in many respects with the problem of “ghost recipients” in its pension system. As of early 2000, the share of fraud totaled to 25 percent of overall payments in the pension system. As a part of the pension system reforms intended to eliminate corruption, the Ministry of Health, Labor and Social Affairs, the government instead created in 2000 the Ministry of Social Security. The Ministry immediately made new appointments in the executive teams of Georgian social security funds and created a computerized pensioner registration system. A special supervisory board and expert groups were formed to improve resources management, and civil controllers were elected to all social security departments. In 2004, the National Agency of Public Registry (NAPR) was created within the Ministry of Justice. A team of software developers created a unified governmental registry system to collect all information subject to state registration — from personal data to property rights.

Greece

Two governmental agencies were in charge of social welfare audits. The lack of information sharing between governmental bodies was the main problem for the Greeks. For example, organizations responsible for death records had no automated system to notify social security funds about death cases. To solve this problem, the development of the national registry of welfare recipients started in 2011. In 2013 two interconnected centralized digital monitoring system were activated. The first, HELIOS, is a centralized social security monitoring system meant to gradually replace 93 legacy industry-specific systems. The system provides statistics about the number of pensioners and the amount of each pension. The second, ARIADNE, is a system to register demographic changes, including births, marriages, divorces and deaths. As a result of verification in 2001–2011, the Greeks suspended social payments to 2 percent of the country’s population (200,000 persons). It has been found that the government erroneously paid about 8 billion euros, primarily in favor of “ghost recipients”.

Australia

In Australia, social expenditure is audited by a special unit within the Department of Social Services. The unit reveals fraud by means of data comparison. The key element of the monitoring efforts is ATLAS (Automated Transfer to Local Authority System) introduced in 2010. The system allows the department to track changes in social benefit recipient’s parameters made in other databases and share this information with local authorities. In 2008–2009 Australia investigated 26,084 cases of potential fraud. The result is 113.4 million dollars saved in 5,082 cases brought to the Prosecutor’s Office.

Considering the level of corruption in Ukraine, an independent auditor in the form of a specialized agency or another body independent from the Ministry of Social Policy could probably be a viable option.

Data-greedy agencies

In Ukraine, verification issues emerged right from the start. Firstly, a unified database to hold the data of all social welfare recipients does not exist. To obtain information, one has to compare databases belonging to different agencies. The process appears to be highly bureaucratized and slow.

Secondly, the situation was aggravated by an unwillingness to cooperate shown by some agencies. The initial plan looked like this: when the verification is launched, the Ministry of Finance starts getting data from the State Fiscal Service, the Deposit Guarantee Fund, the Ministry of Health Care, the Ministry of Defense, the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the Ministry of Social Policy, all insurance funds, the border guard and migration services, Oschadbank, local authorities and other governmental bodies.

But by late March, the majority of agencies refused to provide information citing the absence of bylaws and other bureaucratic reasons.

In February and March, the government adopted several decrees to regulate the financing of verification and some other related issues. This spurred the governmental agencies to share data to some extent, but the problem was not solved completely.

For example, the Ministry of Justice appeared to be one of the most restricted bodies. It blocked the access to the registry of births, deaths and marriages. The registry was needed for the validation of physical state; in other words, it enabled the Ministry of Finance to learn whether a person is dead or alive. Different sources may contain different information about person’s physical state or the date of death. The Ministry of Finance had to use data provided by the State Fiscal Service for this.

During March and June 2016, the Ministry of Finance revealed 4,195 deceased persons based on information the State Fiscal Service had obtained from the registry of births, deaths and marriages. This figure illustrates cases when pensions were either still paid to the deceased or the date of death differed from the pension cut-off date significantly — 100 to 6,000 days (16.5 years).

The Ministry is still unable to access the registries of social welfare recipients, the registry of car owners (the Ministries of infrastructure and internal affairs), the registry of voters (the Central Election Commission), the registry of Ukrainian passport owners kept by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the State Migration Service (only the registry of internally displaced persons (IDPs) is available).

There are several reasons why the governmental agencies are reluctant to share information. First, it is necessary to change the regulatory framework so that the Ministry of Finance can receive unrestricted access to the data. Theoretically, the final provisions of the Budget Code, paragraph 40, give the Ministry the right to obtain any personal data if a citizen has given any of the governmental authorities his or her consent for the access. In reality, the Central Election Commission (the registry of voters) and the Ministry of Justice (the registry of births, deaths and marriages) block the access citing the necessity to change the respective laws. Two laws entitle the Ministry of Finance to access data covered by bank secrecy. The necessary changes were made in a law regulating banks and banking activities.

Second, the governmental authorities do not want to provide access to their documents and databases to outside auditors because of possible intradepartmental conflicts of interests, in addition to the willingness to hide internal information.

Third, many databases are not centralized (e.g., the registry of persons entitled to benefits and the registry of national passports). Thus, it is simply impossible to get consistent information.

The Ministry of Finance obtained information from the Pension Fund, the Ministry of Social Policy, the State Fiscal Service, and 48 commercial banks. Ten regional state administrations are also among the Ministry’s sources. Because of difficulties with quick access to data, the State Treasury’s database became the main source for the Ministry, which allows it to see payment transactions; the State Fiscal Service is another major source. As we’ve already mentioned, this permitted the verification of managers and recipients of 70 percent of social benefits. So what has been found?

Ministry’s recommendations

During three months of verification, the Ministry of Finance provided 513,900 recommendation to various governmental agencies. This will allow eliminating the risks of paying unlawful benefits amounting to UAH 5.23 billion.

According to official statistics, the Ministry sees housing subsidies as the riskiest area.

In this respect, a set of cases when people claim subsidies but exceed the limit on a purchase sum entitling to such subsidies is considered the most problem-plagued. This refers to real estate and land parcel purchases in excess of UAH 50,000. The Ministry believes that 165,949 or 32.3 percent of the total number of such cases are risky —potentially unlawful and have obvious signs of violations.

The Chernihiv, Dnipropetrovsk, Vinnytsia, Volyn and Ternopil regional state administrations were given 71,749 recommendations by the Ministry with regard to subsidies to persons not registered by the State Fiscal Service or having their identification code and registration canceled.

The top three problem areas also include persons who have registered as unemployed and received unemployment assistance but had a paid job at the same time. The Ministry sees risks with relation to 40,173 Ukrainians mentioned in 7.8 percent of recommendations.

Another problem area is welfare benefits for internally displaced persons (IDPs). For example, the Ministry revealed 6,529 cases of social payments to IDPs who received salaries at the territory controlled by the government in the beginning or during the military conflict. Another 8,414 cases relate to recipients who were absent from the government-controlled territory at the moment of their social welfare accounts opening.

There’s a significant group of recipients — 8,893 persons — who were receiving payments while located on government-controlled territory before or during the war. Almost 10,000 IDPs received welfare benefits while owning housing accommodations on territory controlled by the government. According to law, internally displaced persons can receive benefits only if they do not own housing accommodations in a safe area.

All unlawful schemes with IDP payments are the side effects of simplified procedures to claim this type of social welfare. Registration rules and methods of IDP support were approved in a rush. The idea was to make them as clear and simple as possible.

Sluggish response

The verification could have been called a success if it led to half a million of inspections, the disclosure of unfair recipients and the suspension of their social benefits.

But the situation is still far from that. The only governmental body entitled to suspend social benefits is the Ministry of Social Policy that has made decisions to grant them. The problem is that the Ministry of Social Policy and the Ministry of Finance disagree on verification methods. The social ministry believes that there are not enough data and recommendations to initiate inspections and decide on the suspensions.

According to the Ministry of Finance, as of June 6 governmental bodies that had received recommendations to check 513,000 suspicious cases reacted as follows:

- 54 persons were audited by the Ministry of Social Policy;

- 3,810 persons were audited by the Pension Fund of Ukraine.

To make the social agencies react, the Ministry of Finance sent information about potentially unlawful social payments to the State Financial Inspection. The Financial Inspection has its own audit plans. It updated its schedule to include the local bodies of the Ministry of Social Policy, the State Employment Service etc. and started financial verifications. According to the law, the Financial Inspection has to complete scheduled field audits within 30 workdays at the latest; and unscheduled audits should not take more than 15 workdays. By July 6, 2016, the Financial Inspection audited 3.7 percent of recommended cases and found violations in 27 percent of them.

What’s next?

Two scenarios are possible in this situation. The first one is optimistic. In the coming months, the Inspection carries out half a million of audits. This will allow the discovery fraudulent welfare payments and hopefully stop them.

The restitution of illegally obtained benefits to the budget can take different shapes. Utility subsidies are usually entered into a clearing system; i.e., if the subsidy is granted then the utility bill is automatically decreased by the subsidized amount. The recipient doesn’t get cash. In case the subsidy is canceled as a result of the audit, the recipient will be automatically charged an amount equal to the unlawful benefits they’d previously received.

In cases when unlawful social payments have been made in cash, the Ministry is set to recover them through litigation. This can lead to thousands of legal proceedings.

The second scenario is pessimistic. Nothing of the above will happen. Or alternatively, the progress will be partial. Governmental agencies will continue to block access to data. The process of information gathering will linger, audits will be postponed or prolonged. At the moment, this scenario is more likely. The reasons include a management reshuffle in the Ministry of Finance. Deputy Minister of Finance Mr. Roman Kachur has been in charge for the verification before. Recently, the new Deputy Minister of Finance for Local Budgets and the Humanitarian Sector Mr. Sergei Marchenko took over the task. Mr. Marchenko is studying the scope of future verification work now.

There is a high probability that under both scenarios the Ministry will face counterclaims, cases when recipients have no money to repay the debt or simply escaped. It is hard to forecast when the government can return social benefits paid to swindlers and whether it can recover them at all. Most probably, the main advantage of the verification is the prevention of such losses in the future.

The thing is that this year’s budget has been made with consideration of the audit. If the saving is not achieved “in real time”, then the government will need to find resources to cover the amount.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations