Ukraine’s resilience to the Russian Federation’s War of Aggression was first met with surprise and eventually with admiration among millions of people around the world. Most analysts attribute Ukraine’s success to the skills of the Armed Forces, the military and economic support of partner countries, as well as the national mobilization and patriotism of Ukrainians who faithfully defend their country. Nevertheless, there is another factor that is less often mentioned in analytical materials. This is the effectiveness of institutions, in particular, at the level of territorial communities (hromadas). We are talking about specific efficiency, which we call resilience later in the text. It was this factor that contributed to the ability of local governments, volunteers and the local population to work together to deal with the shocks faced by local communities.

The study of the resilience of territorial communities to the challenges of war and the impact of decentralization reforms on it, is part of a long-term study by the Center for Sociological Research, the Study of Decentralization and Regional Development of the KSE Institute in partnership with the “U-LEAD with Europe” Program, financed by the EU and its member states – Germany, Poland, Sweden, Denmark, Estonia and Slovenia.

Hromada’s resilience

Our team views “hromada’s resilience” as the ability of executive authorities to adapt to various shocks of a full-scale war (in the first 9 months). Thus, we take into account the fact that full-scale war is not a single shock, but rather a source of shocks of different intensity, duration and complexity in different areas for different territorial communities. For an initial understanding of what prerequisites and practices contribute to sustainability in communities, in August-September 2022, we conducted 8 in-depth interviews with representatives of four categories of communities:

- Hromadas that were first occupied and then de-occupied as a result of successful counteroffensive actions by the Ukrainian Armed Forces.

- Hromadas that were under occupation at the time of the interview (respondents left these communities and were safe).

- Rear hromadas that are relatively close to the front line.

- Rear hromadas which are significantly distant from the front line.

Statistical data (adjusted for inflation) suggests that communities respond differently to the economic shocks of a full-scale invasion. The total volume of own tax revenues decreased in the absolute majority of hromadas. Only a few dozen territorial communities were able to maintain it at the pre-war level or increase it. Among them, for example, communities where there is an extractive industry and which were not affected by shelling, or industries whose production chains were not affected by the shelling.

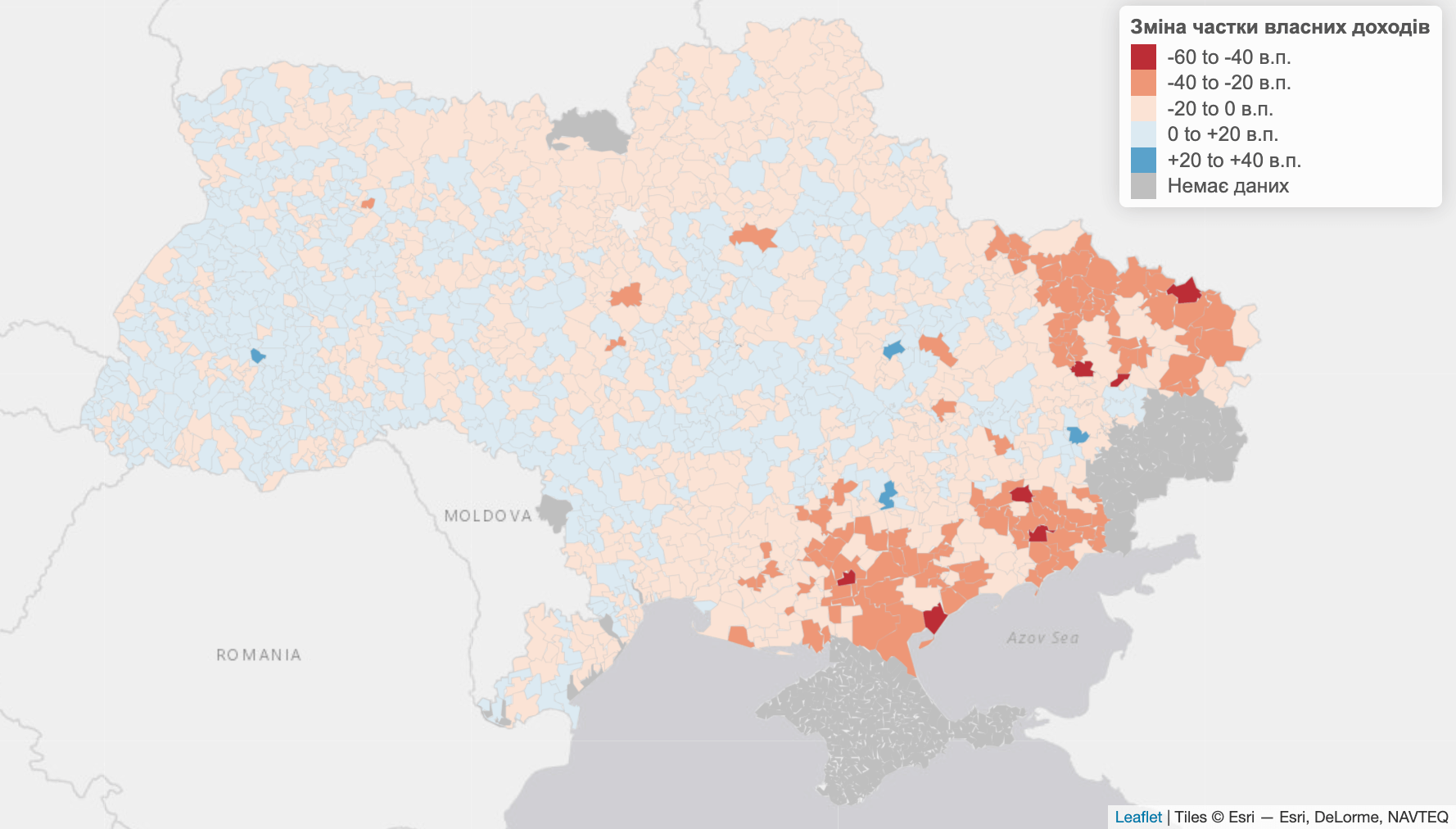

At the same time, the share of hromada’s own revenues (all revenues except transfers from other budgets) in its total revenues decreases with the proximity to the areas of hostilities. In communities close to the frontline, the share of own income fell by 40-60 percentage points (due to shutdown of enterprises and evacuation of part of the population), while in communities located further from the active fighting, the share of own income decreased by 10-20 percentage points, and in some of them it even increased.

Figure 1. Changes in the share of hromadas’ own incomes without military personal income tax in the overall community income structure (March-July 2022 compared to the same period last year), adjusted for inflation. Data source – Openbudget

We also see significant variability among territorial communities in the rear. In some hromadas, the share of own revenues in the budget decreased to 20 percentage points during March-July 2022 compared to the same period last year, and in some cases this indicator increased by 20 percentage points. Excluding military personal income tax, the difference, although not so significant, remains. Within one oblast, in some hromadas the share of their own revenues increased by 5-10 percentage points, while in others it decreased by 3-7 percentage points. (Figure 1).

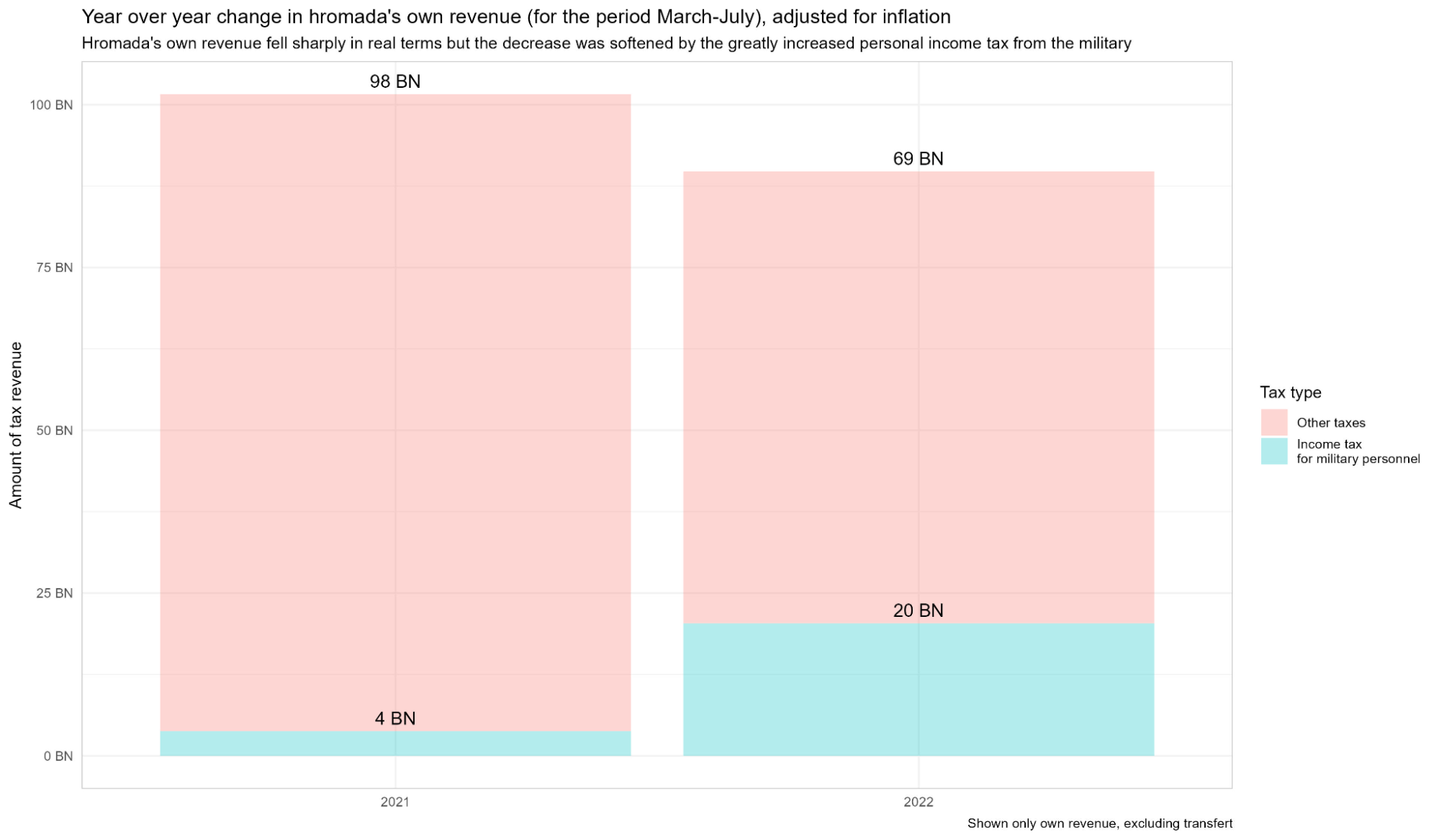

Revenues from the personal income tax of the military significantly mitigated the reduction of resources at the disposal of territorial communities. In 2021 the personal income tax of the military was 4% of the total amount of own income, but in 2022 this share will be almost 29%. There was growth in real terms as well – 5 times (Figure 2). The fact that the location of military units on the territory of Ukraine does not depend on community decisions puts territorial communities in unequal conditions for further economic development, because some communities have to make much greater efforts to fill the budget than others.

Figure 2. Annual change in the community’s own income (for the period March-July 2021 and 2022), adjusted for inflation

Therefore, not only the communities located in the military zone and the rear, but also the rear communities differ from each other. To understand this difficult situation, we started a pilot study and saw that in order to successfully withstand existing and new challenges, communities need long-term support and exchange of experiences.

Below, we present findings from the interviews to describe the shocks faced by different communities and the factors that influenced communities’ response to these shocks. The identified shocks mainly correspond to the elements of national stability defined in the Concept of ensuring the national stability system, introduced by the National Security Council of Ukraine in August 2021.

Shock 1. Threat to institutional stability

The shock is characterized by the unexpectedness of the full-scale invasion, psychological shock and confusion of people. The shock created additional challenges for community management in the early days of the full-scale war. For most of the community leaders we spoke with, the full-scale invasion was unexpected, so the response to this shock depended on:

- Willingness of the community leadership to remain in hromada and work under martial law

- Ability to quickly change the mode of operation and work overtime (creation of coordination chats, regularity of meetings of the executive power representatives and other relevant structures)

- Level of preparation for an emergency situation (invasion):

- the adaptation of national plans for resistance at hromada level;

- carrying out discussions regarding hromada action scenarios in case of possible crises (invasion);

- the ability to form reserves (fuel, water, medicines), their volumes; preparation of vehicles for evacuating the population and/or importing humanitarian aid

Lessons learned: despite the understanding of the importance of institutional stability, even after the invasion, not all territorial communities have approved resistance plans or prepared plans for escalation, appearance of new shocks.

Shock 2. Threat to security

The risk of missile strikes was and remains in all regions of Ukraine; in many regions, the activities of subversive reconnaissance groups were recorded. Although hostilities did not take place directly in all regions of Ukraine, there is a continuous need to mobilize the population for financial and other assistance to the Armed Forces.

The response to this shock depended on:

- speed of formation of territorial defense forces of the Armed Forces of Ukraine and voluntary formations of territorial communities;

- capacities of civil defense structures (bomb shelters) before invasion and speed of creation/modernization of new ones;

- the extent of assistance to the Armed Forces of Ukraine and volunteer formations by the territorial community.

In June-August 2022, this shock manifested itself in the need to create and test shelters in educational institutions in a short period of time and with limited funding opportunities for the start of full-time studies on September 1.

Lessons learned: interviewed hromada representatives indicated that the cohesion gained in the process of voluntary communities’ amalgamation and “winning the right to its independent existence” contributed to the desire of local residents to help the Armed Forces and other defense formations. Therefore, measures promoting cohesion should remain and be financed in territorial communities. Such activities include involving citizens in decision-making and/or bringing people together around common issues/problems (e.g. participatory public budgets). These can be projects involving residents in the creation of public spaces (for example, these are among the winners of last year’s All-Ukrainian competition “Best Practices of Local Self-Government”). In rural territorial communities, these are often joint projects of several communities or creation of cooperatives within one community.

Shock 3. Informational shock

In social media pages and chats, false information and fakes were widely spread, which led to panic among the local population. If the local authorities did not take action on this, this could lead to an influx of irrelevant requests to the police and the hotline.

The response to this shock included:

- regularity of communication with hromada residents, publication of verified news and mutual assistance within the community;

- frequency of meetings (exchange of information and experience) with other territorial communities.

Lessons learned: even small territorial communities have created and activated social networks to officially inform the population, debunk fakes and counteract information-pshychological operations of the enemy. The hromadas have also created informal partnership relations between neighboring communities for regular updates. Unfortunately, some communities have decreased the frequency of communication with their people compared to the beginning of the full-scale invasion, which has led to dissatisfaction among the population. Representatives of the communities with whom we spoke resumed communication at the request of residents.

Shock 4. Humanitarian shock (influx of internally displaced persons)

In the first months the shock implied the need to quickly find temporary shelter for a large number of people, and provide them with food and medicines. Today the challenge is to provide permanent housing, social integration and employment to IDPs.

The response to this shock includes:

- creation of opportunities for internally displaced persons (beds, places in educational institutions for children, psychological/legal/other support)

- number of displaced enterprises and the number of jobs created

Lessons learned: some hromadas mentioned that their openness to the ideas of NGOs and businesses prior to the full-scale invasion was advantageous, as such cooperation helped organize coalitions in different spheres faster and better. Besides, horizontal connections initiated at various trainings and forums helped respond to this challenge.

Shock 5. Threats to critical infrastructure

Some territorial communities experienced this challenge in the form of additional load on critical infrastructure due to rapid population growth and utility consumption levels (in rear hromadas), while in other territorial communities the challenge was the protection of infrastructure and the need for its rapid recovery in cases of shelling.

The response to this shock depended on:

- The speed of resource mobilization, in particular the purchase of generators

- Diversification of energy supply sources before the invasion

Lessons learned: territorial communities mentioned that investments in utility equipment contributed to a faster and better response to utility outages.

Shock 6. Threats to economic stability

The already mentioned economic shock was due to the limitation of budget transfers during the first weeks of the war, the reduction of tax revenues, closure of businesses, etc.

The reaction to this shock depended on:

- Redistribution of funds from the special fund of the budget

- Intensity of cooperation with foreign partners (receiving grants)

- Communications with businesses for obtaining financial support from the private sector and relocation of enterprises

Lessons learned: hromadas state that their proactivity – encouraging re-registration of displaced persons who are individual entrepreneurs in hromadas, contacting businesses with relocation offers, etc. – yields results – increased tax revenues compared to the first months of the war.

Shock 7. The need for quick restoration in the de-occupied territories

In the liberated territories, large areas of critical infrastructure, housing and social infrastructure were destroyed, a large part of the territory was mined.

The reaction to this shock depended on:

- Opportunities to assess damage for planning future reconstruction

- Opportunities to mobilize funds and networks for recovery and reconstruction projects

Lessons learned: similar to other shocks, the experience of communities shows that having horizontal connections with business, international partners and other agents enables faster and better solutions to the problems caused by this shock.

Conclusions

Pilot interviews with a small number of respondents demonstrate that since the full-scale invasion on February 24, 2022, local communities have faced a wide range of shocks. Responses to some of the shocks started even before the war, to others – already in the process. The next part of our research is to collect statistical data to assess the impact of the identified shocks on hromadas and to examine what factors influence communities’ resilience to these shocks.

The Center for Sociological Research, Decentralization and Regional Development supports territorial communities. We understand that each hromada has its own specific situation, and not everything we have described may be relevant to each hromada. Our research aims to discuss and disseminate information on best practices and failures of community management to help develop resilience at the level of territorial communities.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations