This study seeks to illustrate that Russia’s long history of authoritarian rule has likely led to several negative consequences for the psychology of individuals on a collective scale. Specifically, it has strengthened a significant tolerance for authority control, reducing the inclination for resistance. Additionally, it has heightened perceptions of insecurity, fostering a distorted relationship with authorities and a greater predisposition towards submission and acceptance of government policies. Finally, this historical experience has contributed to the development of collective pride among Russians for the achievements of their authoritative state. The above propositions are examined using data from the World Values Survey collected in 1990 and 2011.

The analysis on why Ukraine is democratic can be found under this link.

In the context of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, there exists a notable sense of perplexity among observers regarding the reactions of the Russian population. The widespread acceptance of information disseminated by the government, coupled with a lack of critical questioning or dissent against the official narrative, demonstrates a peculiar relationship between the citizenry and the authorities in Russia. Equally intriguing is the absence of widespread protests or opposition in response to mobilization efforts. Despite individual dissatisfaction with government policies, this discontent has not escalated into organized mass protests in the country.

This study proposes that the historical evolution of Russia as an authoritarian state has played a substantial role in shaping the current political values and attitudes of its individuals. In particular, I argue that the enduring influence of authoritarian governance structures may explain the observed patterns of public behavior, reflecting the country’s historical legacy. More specifically, the tendency of Russians to have an authoritarian mindset can be traced back to their historical experiences with such a form of rule. These experiences took their roots from the Mongol invasions, during which the Golden Horde established dominance over a large part of Russian territory and imposed a centralized authoritarian system of governance, laying the foundation for the ongoing trend of centralization. Subsequent endeavors to modernize or westernize Russia were consistently failing. Instead, the historical evolution of the state relied on prioritizing reforms directed at augmenting the authority of the central government, a trend that impacted the psychology of the whole nation.

It is crucial to emphasize that this analysis does not focus on the period after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, marked by an initial shift towards democracy in Russia and followed by a subsequent return to an authoritarian form of governance. Instead, the emphasis is on drawing insights from Russia’s long history as an authoritarian state spanning many centuries. The primary goal is to explain why attempts to establish democracy could not be sustained in Russia and why Russia tends to eventually return to authoritarian governance.

Due to space constraints and the presumed familiarity with Russia’s historical evolution as an empire, the discussion on its historical experiences has been omitted but can be found here.

Russia’s history of authoritarian state and the nation’s psychology

It is essential to bear in mind that Russia’s historical trajectory of many centuries has predominantly been characterized by the reinforcement of centralized governance, leading to the prevalence of an authoritarian political culture. This authoritarian milieu carried the potential to generate adverse consequences for individual psychology on a collective scale. According to the self-determination theory, posited by Deci and Ryan, individuals subjected to excessive control often exhibit proclivities toward low self-esteem and feelings of helplessness, fostering a sense of insecurity. If a majority of individuals undergo this feeling of insecurity within the country for many centuries, it may cumulatively transform into a collective apprehension, creating a demand for security and propelling the issue of national security to the forefront of political preferences. This aligns with the contemporaneous emphasis placed by Russians on national security within their political landscape.

Furthermore, the perception of insecurity by individuals exposed to authoritarian environments tends to cultivate a distorted understanding of power dynamics. In particular, they fail to form healthy relationships with authoritative entities by subconsciously accepting the beliefs and values of the oppressor and assimilating them into their own self-concept or value/belief scheme. This phenomenon is in line with the concept of psychological manipulation or internalization of the oppressor’s perspective and usually results in fostering a biased interpretation of actions undertaken by the authorities.

The internalization of the oppressor’s perspective can also contribute to the unwarranted acceptance of limitations and control. Individuals living in the authoritative environment often opt to willingly subject themselves to the oppressor without feeling the necessity to rationalize this submission or use fear as the rationale for submission. The psychological mechanism underpinning this phenomenon is called “learned helplessness,” according to which excessive control and the potential for punishment by the authority create an environment where individuals feel they have little power over their personal and economic well-being. This can lead to heightened feeling of fear and a sense of powerlessness that favour submission. From an economic standpoint, this fear is rooted in the objective reality of the absence of a robust rule of law, characteristic of an authoritarian state. The lack of a fair and transparent legal system undermines individuals’ perception of control over their lives. The fear of potential punitive actions, such as the seizure of property without a means of protection, encourages individuals to submit to the authorities.

This implies that a nation’s protracted experience with authoritarian governance may foster a collective inclination toward submission to the authorities and an endorsement of any of their actions. In accordance with this perspective, recent events indicate elevated levels of submission to the government within the Russian population. Russians willingly or reluctantly yield to the authority, recognizing the legitimacy of any governmental actions and unquestionably accepting its policies.

This inclination towards submission is typically accompanied by a dearth of political and civic activism within authoritarian contexts. Drawing from the psychosocial development theory posited by Erikson (1959), excessively strict or authoritarian environments can impede the development of an individual’s sense of independence and self-efficacy. When individuals experience excessive control and are denied opportunities to make decisions and assume responsibility for their actions, they can develop passivity, hindering their capacity to assert themselves and make autonomous choices. Similarly, the self-determination theory suggests that individuals lacking autonomy and a sense of control are prone to developing a fear of failure and a lack of initiative, leading to diminished resistance to external influences, particularly oppressive ones. This phenomenon may explain the weak political and civil resistance observed in Russia.

Additionally, authoritarian governance played a crucial role in enabling Russia to confront invasions and occupy neighboring territories across its historical timeline. This engendered a sense of national pride among its population, with authoritarianism being embraced as a contributing factor to the country’s historical accomplishments. In line with this argument, recent studies indicate that patriotism in Russia is closely tied to pride in the nation’s historical legacy and geopolitical influence in the region. This perspective is directly linked to the importance placed on the Russian language as a unifying element of the empire and a primary force for exerting influence. There was always a concerted effort to introduce and preserve Russian as the official language of communication in conquered territories, thereby limiting the use of native languages of the conquered populations.

In summary, Russians tended to form complex relationships with their authoritarian state, displaying a notable tolerance for the control imposed by authorities, thereby diminishing the inclination for resistance. The bond with the state directly correlated with an augmented perception of insecurity, coupled with a distorted relationship with authorities, manifested through an elevated predisposition towards submission and acceptance of governmental policies and control. Furthermore, Russians channeled their relationship with the authorities through the prism of national identity founded on collective pride for the historical accomplishments of their authoritative state.

Data and variables description

To test the presence of the aforementioned political values in Russia, we use the data from the World Values Survey. The dataset is derived from a sample on Russian Federation collected in November 1990. For comparative purposes, data from Belarus collected in the same year are employed as a benchmark. The choice of Belarus is justified by the fact that it diverges from Russia in the duration of its historical interactions with authoritative governance. Following the 13th-century Mongol invasions, Belarusian territories became part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, subsequently integrated into the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth by the 16th century. Belarus came under the control of the Russian Empire in the 18th-century with Partitions of Poland. Consequently, Belarusian history with centralized and authoritarian governance traces back only to the 18th century, contrasting with Russia, which initiated centralization and authoritarianism from the 13th century onward.

The analytical approach entails computing average values for attitudinal variables pertinent to the discourse outlined earlier. The underlying assumption is that if a country’s values and attitudes are the result of historical experiences, significant differences between Russian and Belarussian responses should be evident. However, one should consider the possibility that due to the changes brought by ‘perestroika’ and ‘glasnost’ in 1990, a sense of increased freedom and tolerance could emerge. To eliminate the impact of these aspirations on the attitudes, I also include the values for the selected variables from a more recent WVS survey, conducted for both Russia and Belarus in 2011.

The array of attitudinal variables encompasses the following measures: the proportion of individuals identifying with their community over the state, the percentage of respondents deeming the maintenance of order in the nation as important, the share of respondents emphasizing the importance of tolerance and respect for others, the percentage of individuals expressing trust in political parties, courts, and the press, the share of respondents indicating willingness to sign a petition or engage in lawful demonstrations, and the percentage of individuals affirming that granting people more say is personally important to them. The average values for these measures, analyzed separately for Russia and Belarus, are presented in Table 1. Figure 1 offers a visual representation of the respective levels for these variables.

An empirical insight into the psychology of nations: Russia versus Belarus

Overall, the World Values Survey data reveal a greater prevalence of nationalism in Russia compared to Belarus in 1990. Specifically, Belarusians exhibited a strong identification with their community, whereas Russians prioritized affiliation with the state over the community. More specifically, 73.13 percent of Belarusian respondents expressed a sense of belonging to their community rather than the state, while only 45.75 percent agreed with this sentiment in Russia. However, the trend of identification with the state strengthened in 2011 in both countries.

Additionally, Russians emphasized the importance of maintaining order in the nation, a sentiment shared to a lesser extent by Belarusians in 1990. Specifically, 58.83% of respondents acknowledged the importance of maintaining order in Russia, whereas only 44.40% did so in Belarus in 1990. There was a slight increase in this share of respondnets in Russia (65 percent) in 2011 while data was unavailable for Belarus.

Conversely, Belarusians surpassed Russians in the percentage of the population endorsing the significance of tolerance and respect for others (70.17 versus 79.80), at least in the initial sample of 1990. In 2011, these variables barely reached a half of their previous levels.

Figure 1: Mean values for the attitudinal measures calculated for russia and Belarus

Notes: *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1. Some of the WVS questions were not asked in Belarus in 2011. The formulation of the question, 'I feel to belong to the community' changed between 1990 and 2011. While respondents in 1990 were required to choose between feeling close to the state or the community, those surveyed in 2011 were asked to agree with the statement that they feel they belong to the community.

Furthermore, Belarusians exhibited greater skepticism about their authorities, contrasted with Russians who demonstrated significant allegiance, as gauged by the confidence measures. In 1990, approximately 46 percent of Russian respondents declared trust in the communist party, a figure that was only half as prevalent in Belarus (22.59 percent). Likewise, trust to courts was expressed by 38 percent of respondents in Russia, while a lesser proportion (26.01 percent) did so in Belarus. Lastly, around 44 percent of Russians conveyed confidence in the press, whereas only 25 percent of Belarusians expressed this type of confidence. These figures remained relatively stable in Russia in 2011, while Belarusians substantially increased their trust in these institutions, reaching or even surpassing Russians in their confidence levels more recently.

Substantial distinctions between Russia and Belarus were also evident in their populations' inclination to question authority in 1990. In the Belarus sample, 51 percent of respondents declared their willingness to sign a petition, a proportion that was only 44 percent in Russia. Additionally, about 55 percent of individuals in Belarus indicated a potential participation in a lawful demonstration, whereas merely 42 percent of respondents in Russia were disposed to do so. These numbers experienced a slight reduction in Russia in 2011, while data for Belarus were unavailable for this year.

Lastly, Belarusians attributed greater importance to the need for enhanced freedom of speech in 1990 compared to Russians. Approximately 35 percent of respondents in Belarus expressed this sentiment, in contrast to 24 percent in Russia. Nevertheless, in 2011, only 14 percent of people in Russia and 18 percent in Belarus valued freedom of speech.

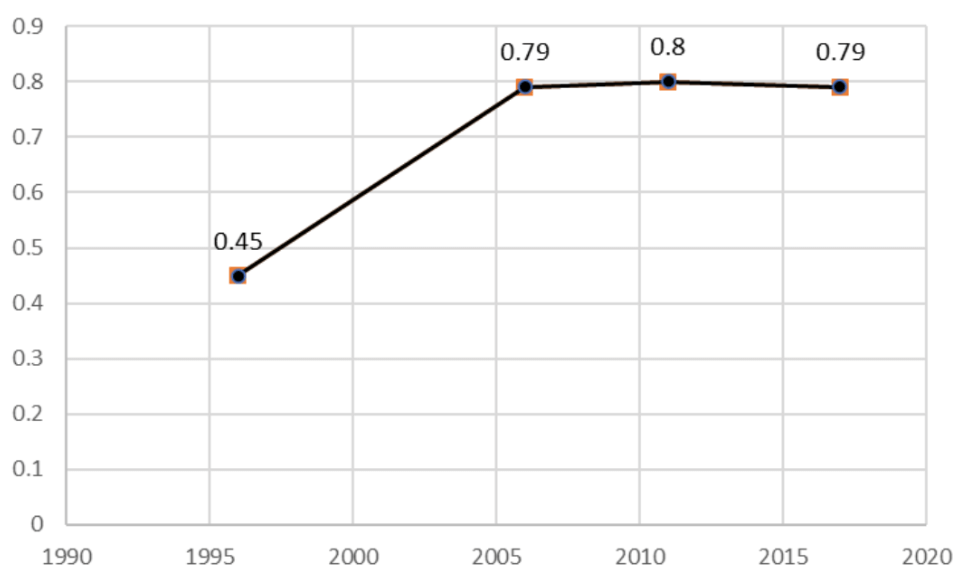

In spite of the above findings, Russians perceived their country as remarkably democratic. The figure below shows average estimates by Russian respondents of the quality of democracy in their country, using a scale from 1 (not democratic at all) to 10 (very democratic). The data indicates that Russians continue to view their country as democratic, even despite significant strengthening of authoritarian values among the population.

Figure 2: The mean values for the perceived quality of democracy in Russia

Notes: The data for Belarus was unavailable because the question was not included in any of the World Values Survey (WVS) conducted in the country.

The differences found between Russia and Belarus in 1990 confirm the aforementioned propositions by indicating that Russians exhibited a more authoritarian political culture, characterized by loyalty to the state, a perceived necessity for maintaining order in the nation, greater trust and reduced skepticism towards authorities, and a lower perceived importance of political or civil opposition. Given that these distinctions were observed in data collected in 1990, when both countries were subjected to the same political and economic context of the Soviet Union, we can infer that disparities in historical experiences with an authoritarian state between the two nations may account for these variations. Importantly, the shared Soviet Union experiences did not manage to completely eradicate these differences, suggesting the existence of path dependence in the evolution of political values and attitudes.

However, subsequent years (2011) reveal that the reinforcement of authoritarianism in Russia continued to influence people's values. In Belarus, the situation was even more pronounced, as the population's attitudes closely aligned with those expressed in Russia. Nevertheless, caution must be exercised in drawing definitive conclusions for findings from 2011, especially in the case of Belarus, as respondents could provide answers aligned with the expectations of the governing regime rather than reflecting their genuine attitudes due to fear of potential prosecution.

What to expect from Russia and Russians now?

The analysis above allows us to draw significant conclusions regarding Russia's invasion of Ukraine. On one hand, Russia might have viewed Ukraine's pursuit of independence and its desire to join NATO as a potential threat to national security. As previously emphasized, security, especially national security, holds paramount importance for Russians.

On the other hand, the conflict can be understood through the lens of Russia's historical identity as a major influence in the region. The war may well be a response aimed at reclaiming Ukrainian territories previously occupied by the Russian Empire and reasserting influence over the Ukrainian population. The strengthening of pro-democratic sentiments among Ukrainians and a shift towards the West might have been perceived by Russia as a risk to its continued influence in the former colony. This potential risk could be seen as jeopardizing the national legacy and pride associated with the idea of Russia as a Great Empire.

This carries significant implications for formulating expectations regarding Russia. Essentially, it suggests that Russians might continue their military actions not only against Ukraine but also against neighboring countries that advocate for democracy. Given that true democracy contradicts the psychology of Russians, efforts to promote democracy can be understood by Russia as attempts to distance themselves from its influence. Consequently, any former colony of Russia striving for democracy is inherently associated with relinquishing Russia's historical glory and legacy. As discussed earlier, this connection holds significant weight in the national mindset. Therefore, Russians will consistently endeavor to take any action, including military interventions, to safeguard this historical legacy.

Moreover, it is unwise to expect that the change in the current situation can happen through a bottom-up mechanism. Russians are unlikely to express political or civil opposition to the government's policies due to their deep-seated value of submission to authorities. This implies that internal resistance from Russia in response to policies related to the invasion of Ukraine is very unlikely. Russians’ overwhelming support for the war can be attributed to the distorted relationship between people and the state, as well as their notable loyalty to authorities. Even in the event of full mobilization announcements, individuals may attempt to evade involvement, but organized resistance is improbable. Instead, the findings suggest that the Russian population is likely to consistently support any conflict or action initiated by the government against Ukraine or any other country. It implies that any war with Russia is not against Putin or the government but against the Russian population.

Table 1: The t-test for differences in mean values of political measures between russia and Belarus.

| russia | Belarus | A t-test for differences in means | ||

| Diff | p-value | |||

| Nationalism and devotion to the state | ||||

| I feel to belong to the community rather than to the state | 45.75 | 73.13 | -27.38*** | 0.000 |

| Maintaining order in the nation is important | 58.83 | 44.40 | 14.43*** | 0.000 |

| Tolerance and respect for other people is important | 70.17 | 79.80 | -9.63*** | 0.003 |

| Skepticism about authorities | ||||

| I have confidence in the political parties | 45.57 | 22.58 | 22.99*** | 0.000 |

| I have confidence in courts | 38.24 | 26.01 | 12.23*** | 0.000 |

| I have confidence in the press | 43.62 | 25.40 | 18.22*** | 0.000 |

| Political and civil opposition | ||||

| I might sign a petition | 44.08 | 51.48 | -7.40** | 0.025 |

| I might attend a lawful demonstration | 42.12 | 54.55 | -12.43*** | 0.000 |

| Freedom of speech is important to me | 24.20 | 34.62 | -10.42*** | 0.000 |

Notes: *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations