While Ukraine is fighting the Russian invasion, the West is preoccupied with the issue of refugees. In addition to looking for funds to cover their stay, the EU is concerned whether these people will eventually return home. Opinion polls generally show that 50 to 80 percent of those trying to escape the war expressed the intention to move back after the situation improves in Ukraine.

This study focuses on individuals returning to their homes after a short period away. The analysis is based on a focus group interviewed at the Lviv and Kyiv train stations [1]. Individuals were asked about their experiences abroad and the leading causes that encouraged them to return to their country.

Ukraine is still under bombing and shelling, with people living in uncertainty and fear. There is no air connection with the outside world, and one can only go to the neighboring countries by bus, by train or by car. Despite this, Ukrainians are coming back, and the data shows that the number of those who return is significantly higher than of those who still try to find peace outside the country. Considering the still ongoing war in Ukraine, many are wondering why Ukrainins are returning? What are the key motivations that encourage them to make this difficult decision? Can it be that their experiences abroad have actually created the situation in which returning became the only option for them.

The current study attempts to provide answers to these questions by exploring the critical motivation behind refugees’ decision to return. The analysis is based on a focus group: we interviewed a small number of people in a moderated setting. Our respondents were individuals of Ukrainian nationality who were returning home after a short period of stay abroad due to the outbreak of the war. Such individuals were found at the Lviv and Kyiv train stations when they were still on their trip back home, awaiting a train to their destination. Since many of them have been spending many hours or even days traveling, it was a real challenge to get these people to participate in the interviews. In addition to tiredness and desperation, one could sense some kind of fear that individuals displayed when asked to respond to my questions. Overall, the response rate was around 10 percent. The sample is, hence, not a representative selection from the population of returning refugees and should not be used for any generalization of findings. Instead, the data and results can be utilized as a source for defining possible explanations for why people go back to Ukraine and who are actually those who tend to return home now [2].

The list of open-ended questions was predefined for the interviews, while a small number of respondents were expected to answer them. In addition to real-time, unfiltered responses, there was room for in-depth explanations of any issue that respondents were willing to highlight. In summary, 36 individuals aged between 22 and 46 (average age 38) participated in the focus group [3]. All respondents were females, out of which 58% were married and had children. 75% had higher education. A relative majority returned from Poland (42%) and Germany (25%). The remaining came from Bulgaria, Romania, Slovakia, and Greece, as summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Countries from which Ukrainian refugees who participated in the study returned

Source: Author’s calculations based on own data

Out of those who agreed to respond to my questions, only 25% had refugee status [4] recently introduced by the EU to legitimize those fleeing the war in Ukraine. 75% avoided declaring themselves as refugees in the attempt to remain flexible in their movements between countries. Many of them viewed refugee status as something that could limit their freedom to relocate. For instance, Natalya (43, Kyiv) explained, “I thought that getting refugee status would tie me to this particular country and would impose numerous bureaucratic obstacles if I decided to return to Ukraine or change my location in case I am dissatisfied with the current one.”

The majority of my focus group were hosted by their relatives or friends (33%), some rented an apartment (16%) or stayed at a hotel (8%). Those falling in the last two categories were initially provided free accommodation by local activists, volunteers, or refugee camps. Unable to cope with the living conditions there, they had to find a new place to stay on their own, often paying for their accommodation themselves. The remaining 33% stayed with unfamiliar people who hosted them, still having mixed feelings produced by this experience. As I show below, accommodation was one of the influential factors behind people’s decision to return home.

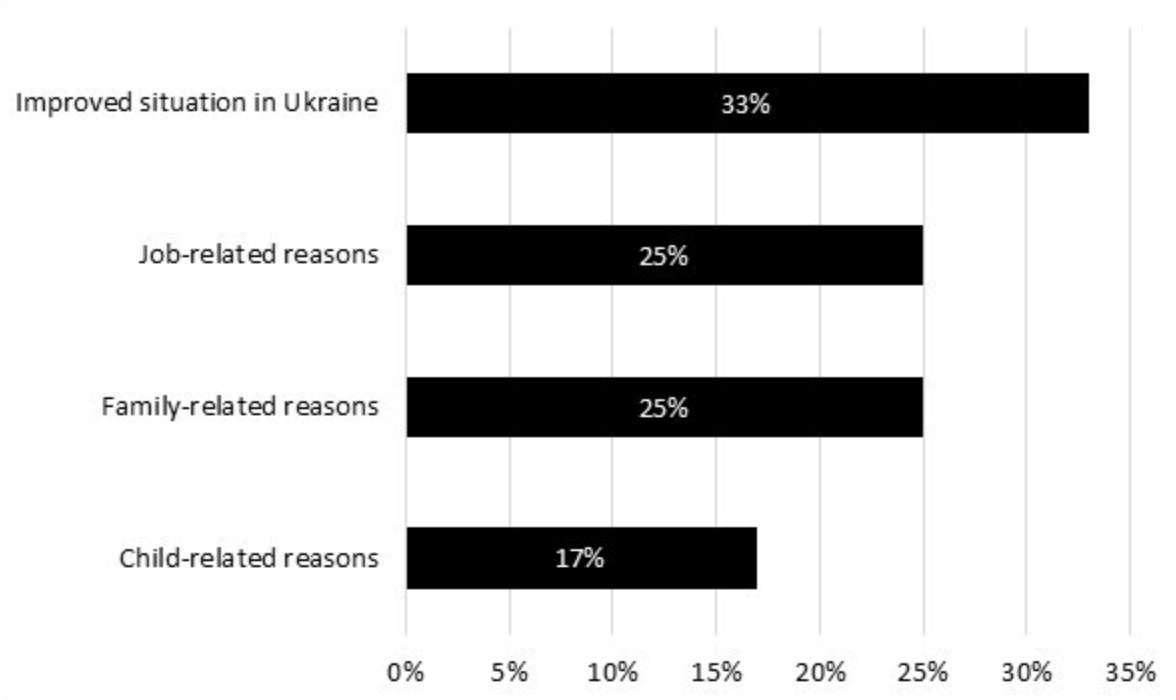

When asked about the primary reason to return, the main explanation provided by my respondents (33%) was closely related to either the need or desire to unite with their family in Ukraine (husbands, parents). For instance, Olena (28, Kyiv) explains her return from Poland by saying “I just could not stand staying there anymore. I wanted to go back home.” This line of reasoning is commensurate with what is reported by many leading newspapers as a dominant motivation for people to return to Ukraine. Also, a great share of my focus group (25%) viewed a relative improvement in the overall situation as a reason to go back to their country. As Olena (32, Kyiv) said “Kyiv is free now and, hence, I can return home. There can still be bombing, I do not exclude this, but the probability that it may hit my house is not that much bigger than the probability that I will be hit by a car on the roads of Bulgaria.”

A quarter of my respondents declared that they were returning because of their jobs. For these people, the fear of losing their source of income in these uncertain times surpassed any danger of being killed. For instance, Kateryna (33, Kyiv) said: “It is nearly impossible to find a job now. I love my job and the pay is better than what I can potentially have in Poland. So I prefer to risk my life but keep my job…. I do not want to spend my life serving tables, even if it is in Poland.”

The rest of the focus group emphasized various problems their children experienced as the most significant factor in going back to Ukraine (a chronic disease that requires constant treatment through medication, unacceptable conditions for a long-term stay with babies, foreign language, etc). Especially challenging for this group was finding treatment for their children in case of contingencies. My overall impression was that it was not the lack of healthcare provision that created obstacles but rather insufficient knowledge and consulting about where to go in case of emergency. When abroad, most Ukrainians were guided by the knowledge derived from the Ukrainian system, and thus medical treatment for them turned out to be either inappropriate or very expensive. One mum, (Maria, 35, Kyiv) said that “Upon arrival in Germany, my child had a very high fever (40 Celsius). Scared, I called an ambulance. I was lectured by the personnel that there was no need to call an ambulance only because the child had a fever. A few days later, I received a bill for 300 euros that I had to pay for the unjustified ambulance use.”

Figure 2. Main reasons that prompt Ukrainians to return

Source: Author’s calculations based on own data

My focus group provided equally diverse explanations when asked about a secondary reason for returning. The overwhelming majority declared that they wanted back home, which points to the psychological exhaustion and disruption the war caused to their daily lives. Smaller shares indicated the need to join the family and the improved situation in Ukraine as second most important reasons to come back. A third of respondents mentioned the lack of financial resources or proper accommodation as principal grounds to interrupt their stay abroad.

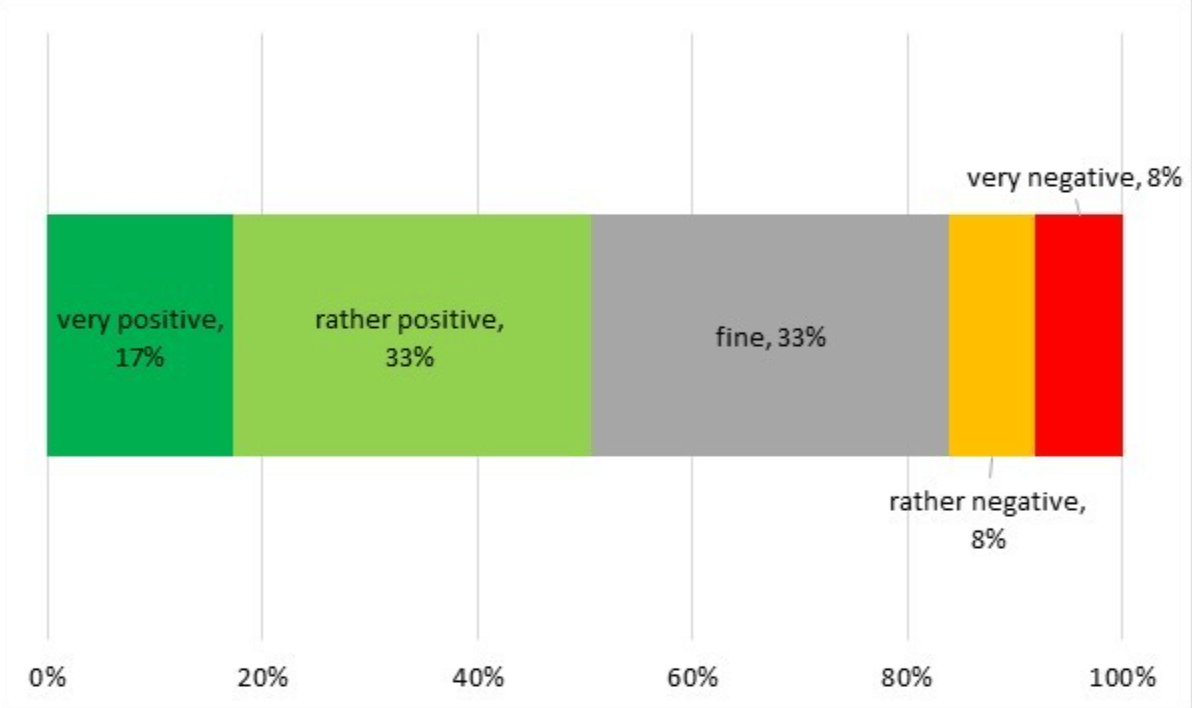

My analysis also showed that one’s overall experience abroad was relatively positive (see Figure 3). Most of my interviewees rated their stay as “somewhat positive” or “very positive.” When asked about the most valuable aspect of this experience, they primarily mentioned the friendly attitudes and understanding the other nations showed towards them or their situation. A third mentioned the efficient assistance with finding a job abroad during their stay. A quarter indicated the opportunity to travel abroad as something that made them feel well during their stay away from home.

Figure 3. Self-rating of experience abroad by Ukrainians who returned

Source: Author’s calculations based on own data

While describing the most negative experience, almost a half of respondents referred to cases of either misunderstanding or difficulties caused by poor linguistic skills. About a third of my respondents said that they faced severe problems finding analogs for medicines they were taking in Ukraine. This experience was especially harmful to women with children who had chronic diseases. Respondents returning to Ukraine from Germany also mentioned hostile attitude to them by German residents of Russian descent.

About a quarter mentioned some disappointment with working conditions or salary when finding a job in the recipient country. Thus, Maryna (35, Kharkiv) furiously described her experience in Poland as deception: “While talking to the employer, I was promised a certain wage and working conditions, which turned out to be very different when I started to work. There was no employment contract, and, in the end, I was not paid even half of the promised money.” As recent reports show, Ukrainian refugees, even those with higher education and many years of experience as high-skilled professionals, had to take non-qualified low-paying jobs.

Despite my respondents’ diverse experiences, they all gave the same answer when I asked where they see themselves in 6 months. They said that they could see themselves only in Ukraine. If this is the case, their personal experiences may become a significant factor in changing Ukraine. On the one hand, Ukrainians who fled to other countries faced new conditions shaped by these countries’ distinct political and cultural settings. Thus, those who return may attempt to implant the positive elements from abroad into the Ukrainian context. These positive aspects can take various forms ranging from food and the way of decorating houses to the overall lifestyle. For instance, Oksana (29, Dnepropetrovsk) mentioned that “People in Germany are somehow more athletic, and they pay so much attention to what they eat, whether what they do is healthy or not. This is something that is valued not only by individuals but also by the labor market. We need to try to become like Germans in this respect.”

Returning refugees may have adopted new visions of how the state and its institutions should function, how much security can be provided to citizens in the case of contingencies, how the healthcare and education systems should be organized, or how attitudes toward each other can be shaped. For instance, Olga (37, Odesa) was enthusiastically talking about the German health insurance system that allows one to get medicine for free with a prescription from a doctor. “Can you imagine how many people this system could save from poverty in Ukraine, especially the elderly or families with children?” she said in the end. Olena (38, Zaporizhia) described the job search support in Germany through public employment agencies as something that should exist in Ukraine: “First of all, it is free, and they have a perfect system of trying to match your skills to the existing job openings…” The emergence of these visions is an essential element that may define a profound transition in Ukraine by influencing the formulation of demand for reforms or preferences promoted through the electoral system.

On the other hand, Ukrainians’ mass exodus to other countries created disillusionment regarding better living standards abroad than in Ukraine. Many of my respondents referred to negative aspects of discrimination and limited opportunities that one may experience as an immigrant in any EU country. This made them realize that their home country could offer better opportunities and rights in many dimensions of life or work. Finally, the majority of my focus group saw that Ukraine is not that much behind many EU member-states. Of course, there is still a long way before Ukraine’s quality of life gets closer to that in Germany, for instance. Still, many think that the country is on the right track and can offer decent living conditions. As Maria (34, Kharkiv) described, “I am a lawyer in Ukraine. My income is sufficient to have the same living standards as an average German enjoys… I am not sure that if I stayed in Germany, I could still work as a lawyer and maintain the same quality of life or social status as I had at home.”

Despite all these optimistic findings, I restrain myself from making any predictions regarding how fast and how many of those who fled Ukraine will eventually return. These trends depend on many factors relating to both personal and overall situation in the country. Suppose the West does not take rapid and comprehensive measures to help Ukraine in this war. In that case, the devastation may take a more significant scale, making it very difficult for the refugees, especially those from affected regions, to return. The economic consequences are also likely to be an essential factor influencing this trend. Even those with jobs in Ukraine can still prefer to stay abroad if inflation continues to rise, and they see their incomes devaluing to unacceptable levels. In the end, not only will those abroad stay there, but even more Ukrainians may decide to leave the country. Immigration will become the only way for them to survive the war or its consequences. This suggests that the focus of discussion in the West should shift from helping Ukrainian refugees to helping Ukraine win the war. Since the right strategy is treating the cause rather than mitigating symptoms. After all, there would be no refugees from Ukraine if there were no war.

[1] The author thanks Natalya Tamilina for helping with the focus group interviews.

[2] Note that the focus group analysis was conducted between the 10th and 20th of May and, hence, only events that happened till that moment could be used to explain the findings and results.

[3] I do not calculate the sampling error for the sample of my interviewees since there is no precise information on all the people returning to Ukraine. This prohibits the calculation of the population means and population standard deviation that are necessary to analyze how my sample’s characteristics deviate from the overall population of returning individuals. I again emphasize that due to this, the data and results of my analysis should not be used for any generalization. Instead, they should be perceived as an attempt to define a possible, even if not complete, list of reasons that may explain one’s decision to return to Ukraine. Briefly, my study aims to shed more light on the issue of the grounds that encourage or enable Ukrainians who were fleeing the war to return home.

[4] In asking about refugee status held by my respondents, I did not distinguish between the old procedure that the EU applies to everyone and the new procedure introduced for Ukraine in response to the Russian aggression. My fundamental understanding was that my focus group participants fled Ukraine during the outbreak of the war, and hence getting the EU regular refugee status that, on average, requires six months, would not be an option for these people. In addition, my analysis did not focus on the impact that a particular form of the legal status of refugees may have on one’s decision to return. Therefore, it was beyond the scope of my analysis to define precisely the type of refugee status that those returning to Ukraine had.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations