If you look at the history of the word, an industrial park is a zoned area, planned for industrial use (see definitions here and here). This zoning is traditionally made to facilitate logistics operations, although sometimes there are other reasons, such as political cooperation (Kaesong between North and South Korea, Suzhou between China and Singapore). The basic idea behind the creation of industrial parks is easy access to infrastructure, raw materials, and labour, as well as the possibility to export finished products. There are usually no tax and customs incentives, although there are exceptions.

What is proposed in Ukraine, in fact, is not a “classic” industrial park, but a return of what has already been there — free economic zones and territories of priority development. At VoxUkraine, we have already argued that their creation did more harm than good to the country than good. The problem here is not only the opportunities for not paying taxes and duties to the budget, which reduces the government revenues, but primarily in the creation of unequal rules of the game, which that affect the whole economy.

A reason politicians all over the world tend to promote tax incentives in the garb of SEZ, TPD, or industrial parks, is the complexity of measuring their economic impact. In real life, from an economic perspective, business incentives of a given size are equivalent to a subsidy for the same amount. At the same time, it is easy to notice a subsidy and argue whether it represents the best use of available resources, whether the effect on the economy will be higher than when directing these funds, for example, on education or the construction of infrastructure facilities. And in the case of tax incentives, the costs are not so obvious — therefore, it’s much more difficult to assess its feasibility and effect.

To show the difference between the proposed draft laws and the way industrial parks operate in other countries, let’s take a look at the Tahoe Reno Industrial Center (TRIC) in Nevada, which is cited as an example by MP Victor Halasiyuk — a supporter of the idea of industrial parks in Ukraine.

First, the creation of this industrial centre was preceded by negotiations between representatives of the state and Tesla Motors, where the latter committed to invest in a plant producing lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles and create 6.5 thousand jobs. In Ukraine, it is proposed to adopt theseis laws without initial negotiations with potential investors, that is, without knowing their needs.

Secondly, the state contracted an independent research centre to perform a third party economic analysis to quantify the impact of the investor’s operations based on the propositions. Today, there are certain doubts about the quality of this analysis, in particular, about its optimism and neglect of some expenses incurred by the state. In Ukraine, there are no estimates of the possible impact of these laws, except for the phrase “The draft law will not require additional expenditures from the State Budget of Ukraine and local budgets” in the explanatory note.

Third, the main advantages of the TRIC, according to the centre’s website, are not tax incentives but access to the railway track, electricity, water, and gas supply. Low tax burden pressure — though not in the industrial zone, but in the entire state — is mentioned in the end of a more detailed prospectus. In Ukraine, infrastructure and logistics problems are significant — according to the latest Doing Business data, Ukraine ranks 130th among 168 countries on the ease of getting electricity, being significantly outranked byinferior to almost all the neighbouring countries. At the same time, draft laws on perks of industrial parks are somehow focused on taxes, rather than on solving the infrastructure and logistics problems.

| Economy | Dealing with Construction Permits | Getting electricity | Registering Property |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poland | 46 | 46 | 38 |

| Slovakia | 103 | 53 | 7 |

| Romania | 95 | 134 | 57 |

| Belarus | 28 | 24 | 5 |

| Russian Federation | 115 | 30 | 9 |

| Moldova | 165 | 73 | 21 |

| Turkey | 102 | 58 | 54 |

| Ukraine | 140 | 130 | 63 |

Finally, there’s the statement of Elon Musk, Tesla founder and CEO, saying $1.3 billion is the maximum tax incentive that Tesla could get over 20 years, an average of $50 or 60 million a year, while the technology park’s planned output is up to $15 billion a year, meaning the incentive is only 0.3%-0.4% of the future revenues. The tax incentive didn’t affect the decision to open the plant (literally, “It does not move the needle on economics”).

Even under these conditions, these tax incentives have been criticised by American research centres — for example, Tax Foundation. And the actual increase in the number of new jobs falls short of the target.

To sum up, Ukrainian “industrial parks” will rather resemble “semi-criminal free zones” (quociting Leonid Kuchma), or the Russian Skolkovo, but not the industrial centre created by Elon Musk.

When talking about industrial parks, people usually focus on the industrial development, as its name suggests, as opposed to the development of other kinds of economic activity, such as agriculture, transport, or IT sector. Thus, parks should lead to the industrialisation of the economy through government actions.

Supporters of dirigisme argue that the economic development of successful countries, especially those of Southeast Asia, has included the development of the manufacturing industry. It is true, as the experiences of Japan, South Korea, China, and other countries show. However, this development was:

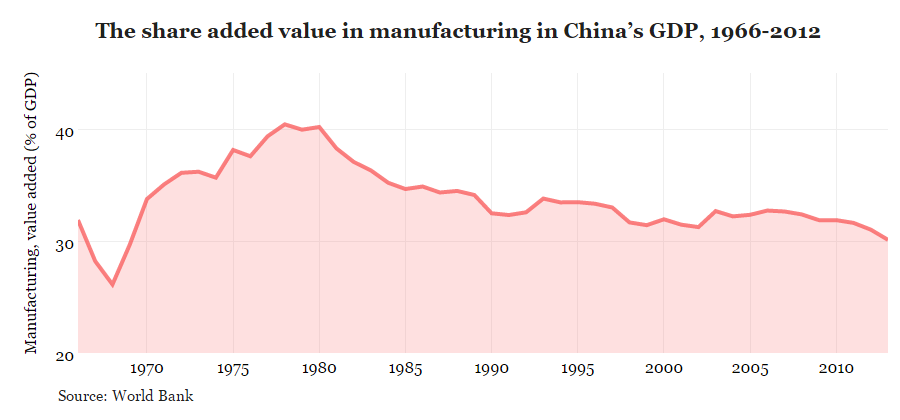

If business development conditions are not created, stable long-term growth is impossible — this can be seen in the attempts to industrialise China and North Korea using the Soviet model. Formally, the share of manufacturing in China’s GDP reached a peak of 40% in 1978-1980. The first stage of reforms was launched by Deng Xiaoping in December 1978 — that is, at a time when the share of manufacturing was the biggest, but the industry itself remained very inefficient. The share of manufacturing in China’s GDP has been declining since then.

In its turn, the transition of labour to the manufacturing industry is a classic recipe for economic development of developing countries (see, for example, the works of Arthur Lewis). It results not only in a higher output, but also in an impetus for the development of education, which enhances future output. However, in today’s Ukraine, with its educated (at least, according to the official statistics, the quality of education is an important separate issue) labour force, it’s not the key driver for of additional development of the education system and, consequently, of the knowledge economy.

It’s necessary to be aware of the conditions for development in such emerging economies as South Korea or Japan. In the beginning, their physical or human capitals were nothing to boast off. People were ready to work 10-12 hours a day earning miserable wages and lacking social protection. Japan went from 48-hour to 40-hour work week only in the 1990s. The successful Asian Tigers started with a fairly closed economy — for example, in 1950s, exports of South Korea accounted for only 2% of GDP, and consisted mainly of agricultural products, seafood products, and products of the mining industry.

Industrial development began with the labour-intensive light industry, which could quickly absorb labour force from agriculture. It is also necessary to note the limited environmental protection during modernisation — a sacrifice the countries had to make at that stage of development. Moreover, social security standards were virtually absent back then, further reducing manufacturers’ costs. In China, even now, about half of the elderly population in rural areas are not entitled to a pension.

Ukraine is already a small open economy (exports / GDP ratio of about 50%), with a trend towards population and labour force decline. Some 17% of the country’s workforce is employed in agriculture — more than in most countries of Central and Eastern Europe, but significantly less than at the beginning of industrialisation in other countries. A substantial part of the employed Ukrainians work in the service sector, primarily in trade. For comparison, in South Korea in 1963 (the beginning of active growth), employment in agriculture accounted for 63.4% (see here, page 480), and in China, even in 1990 (ten years after the start of the reforms) — for 53,4%.

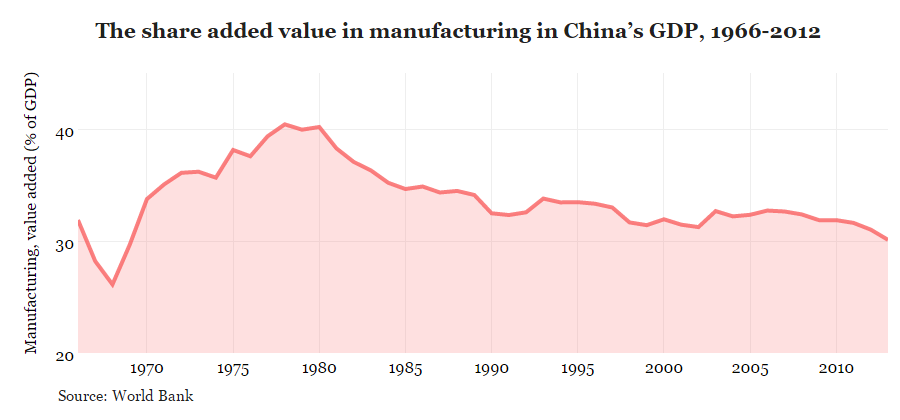

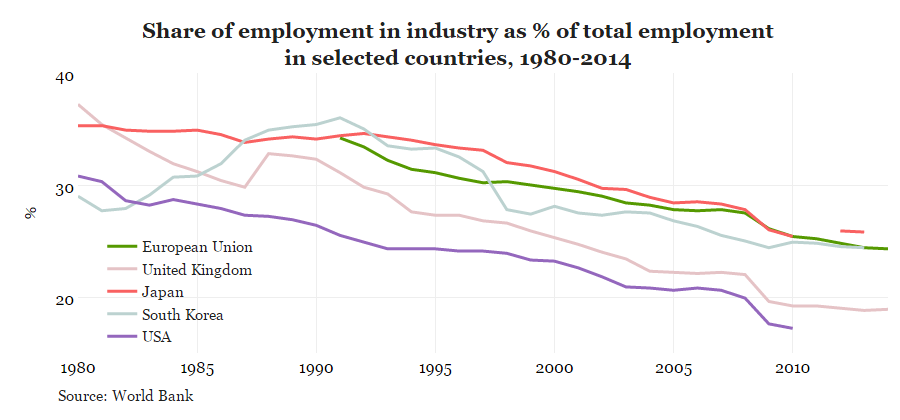

In recent decades, deindustrialisation, that is, reduction of the share of manufacturing in GDP and the share of manufacturing in employment, took place in many countries. This is due primarily to the rapid pace of productivity growth in manufacturing and higher labour demand in the service sector. Moving production to low labour cost countries has also taken place, though it was not a decisive factor. For example, in China, the decrease of the share of manufacturing in GDP started from the very beginning of market reforms and attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) and production. Most economists do not consider this trend a threatening one, though, there are alternative views on the impact of such trends on developing countries.

The development path taken by the countries of South-Eastern Asia some 40-50 years ago is hardly acceptable for today’s Ukraine — especially, taking into account our population structure and economy openness.

A common argument in favour of industrial parks or any other incentives are success stories of the countries that introduced such preferences. But no one talks about the failures. Thus, it is concluded that these incentives have led to an “economic miracle”. Similarly, looking at the success of lottery winners we could conclude that the best way to prosper is to play the lottery.

The actions of the government, successful in one country, often don’t bring the same results in other countries. For example, China is often cited as an example of the successful use of special economic zones (SEZ). Chee Kian Leong (2013) research shows that, indeed, the creation of 4 SEZs in China in 1980 and another 14 SEZs in 1984 likely had a positive impact on the economic development of the People’s Republic of China. At the same time, India introduced its first SFEZ (more precisely, EPZ, export processing zone) in 1965, which didn’t lead to consequences similar to the Chinese. Moreover, India’s weight in world trade fell from 2% in the 1950s to 0.5% in the 1980s. The study emphasises that the success of the SEZ is inextricably linked with the general liberalisation of foreign trade. Export growth has a positive effect on economic growth, but in the absence of other reforms, this influence is quite modest.

The best way to assess the impact of incentives is to do not an isolated case study, but a whole set of such experiments. Just as in the case of lottery tickets, we must know their value and quantity to say whether the game is at least in long run economically advantageous. Unfortunately, in practice this approach faces the problem that each country has its own set of initial resources and policies. Despite these limitations, there are several studies that focus on how tax incentives affect economic performance, most notably their effect on foreign direct investment (FDI), gross fixed capital formation (GFCF), and research and development expenses (R&D).

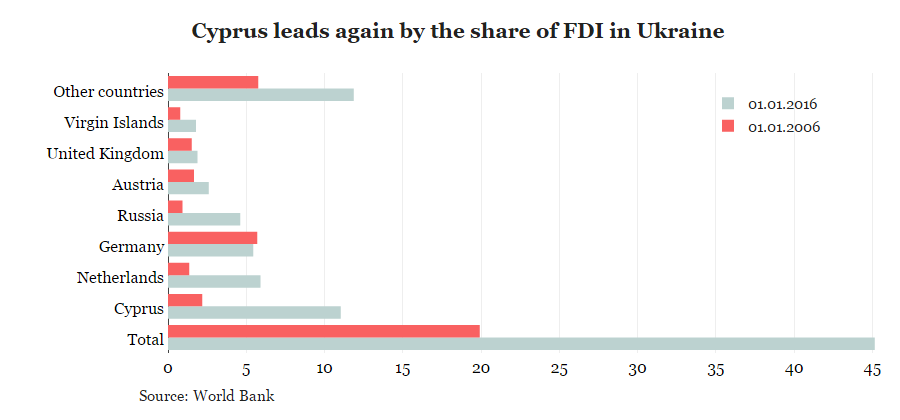

According to the meta-analysis based on 25 empirical studies on the impact of taxes on the allocation of FDI, in most studies, there’s a significant inverse relationship between these indicators with elasticity at the level of 3.3. That is, a 1% reduction of the tax burden increases FDI investment by 3.3%. At the same time, FDI is only part of the overall investment in the economy, and it is important whether the total investment grows when the tax burden is reduced. The paper by Klemm & Parys 2012 uses the dataset of tax incentives in over 40 countries to show that FDI growth (caused by tax incentives) doesn’t lead to an increase in total investment, that is, in this case, FDI is believed to replace other investments. In addition, FDI can be not a real investment, but a means of tax optimisation (for example, money is transferred to “Cyprus”, and then invested in “Ukraine”).

There’s an impact of tax incentives for R&D. However, for example, the Bloom & Griffith & Van Reenen (2007) research of 9 developed countries (which means well-functioning institutions) in the period of 1979-1997, shows that the long-run effect of tax incentives is approximately equal to their volume, while short-run impact is much lower. It means that the incentives are just as effective as subsidies for R&D, which can be provided at the expense of taxpayers in the absence of incentives.

Economic theory shows that industrial parks and dirigisme are suitable only in certain cases. In particular, the most popular argument in favour of dirigisme is the “infant industry” theory. That is, a certain branch of economic activity becomes competitive only when it reaches a certain scale of production. To reach it, the newly formed industry needs temporary support: tax incentives provide resources for investment and R&D activities, and customs restrictions protect the industry from outside competition. Thus, industrial parks and dirigisme help support the new (innovative) industries.

In practice, it’s almost impossible to create such conditions. Studies show that the industries getting this support are not the new ones, but the shrinking (maturehistorical) industries (e.g., mining). Why? In most cases, because of their greater political weight and lobbying potential. Since it’s impossible to limit the political influence of the shrinking sectors, a more effective way to support “infant industries” is a [direct] support of R&D. However, it doesn’t need “industrial parks” as proposed in Ukraine!

Quite often, when citing success stories of tax incentives to attract investment or create jobs, apart from the cost of these benefits for the budget, people don’t consider the fact that tax incentives distort economic stimuli. For example, if area domain A introduces tax incentives, the company, which otherwise would be working in the area B because of its better logistics and suitable labour force, moves its production to area A. Thus, the total number of jobs in the country doesn’t increase. On the contrary, there’s the inefficient allocation of resources.

On the other hand, many companies in the extractive industries are critically tied to the places of mining operations and, accordingly, they would create capacities without additional benefits, especially since the fluctuations in world prices of the resources often exceed any tax incentives.

Therefore, “industrial parks” and “support for new companies”, currently proposed in Ukraine, look good only in theory (though not always), but in practice almost always (and always in countries with weak institutions) result in budget losses and distortion of economic stimuli.

Summing up, it can be noted that:

ПCreation of the draft laws offering tax and customs incentives under the guise of introduction of “industrial parks” are, in our opinion, a sign of the reforms’ success. The thing is that pro-government elites lost their usual sources of rent-seeking because of a more transparent public procurement, better management of state enterprises, etc. It pushes them to find new (or return to old) rent-seeking sources. The task of the civil society is to prevent the return of more extractive institutions, because they are the cause of the country’s low economic development (see Acemoglu, Robinson). We only begin the path to building a country of equal opportunities, that’s why creating incentives for certain companies or industries would mean that we are led astray once again.