VoxUkraine thinks that it is crucial for our country to continue cooperation with the IMF. Ukraine needs the IMF money and financing from other donors anchored to it. Ukraine needs foreign expertise and advice. Ukraine needs to break the tradition of failed IMF programs and to show that this time is different – that it can be viewed as a trustworthy partner. Most importantly, Ukraine needs reforms stipulated in the program.

The history of the Ukrainian government is a history of its inability to commit to reforms. Indeed, even if started, many reforms were scrapped half-way, sometimes worsening the situation. The examples are abundant. The government promised to reduce the regulatory burden on business. According to the “Ease of Doing Business” index, it did not happen. The government announced its plans to reform the pay-as-you-go pension system into a three-pillar system. It did not happen either and the state pension fund runs chronic deficits. The government pledged to establish market prices for gas for households. It has not happened yet and at the beginning of April the Cabinet decided to postpone another round of tariff increases at least till May.

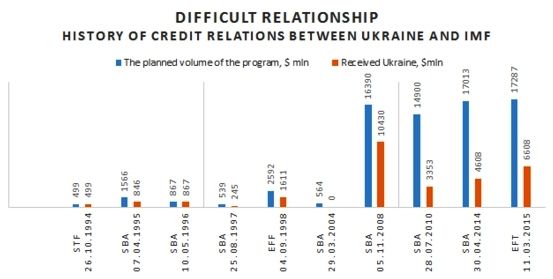

In a similar spirit, the government does not hesitate to change course in its dealings with international partners. We all remember how suddenly Viktor Yanukovych ditched plans to sign an EU-Ukraine trade deal that was years in the making. Ukraine had many programs with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) but none (!) was completed. In most cases, IMF-Ukraine programs were put on hold or cancelled after the Ukrainian government received the first few tranches from the IMF because the government failed to deliver on its promises.

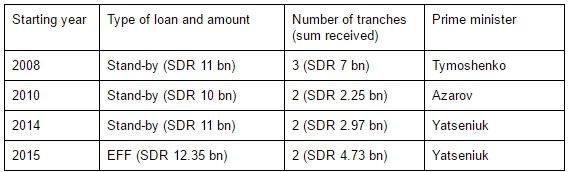

Table 1. The last four programs with the IMF (1 Special Drawing Right (SDR) = 1.41 USD)

Source: IMF data

There are many reasons for this dismal track record. Transition from the Soviet regime with one-party rule and centrally planned economy to a multi-party democracy with a market-based economy has not produced a stable political environment. Often, parties in one election did not exist in previous elections. With this high turnover of political brands, voters are easily confused by political operators repositioning into a new bloc, movement or party (even the current parliament has very many incumbents). This has been further exacerbated by poor protection of property rights and extractive nature of the economy which stimulates short-termism in economic decisions. Whatever is the reason, it is abundantly clear that the Ukrainian government — and more broadly Ukrainian political elites — do not want to take short-term pain to improve the country’s long-term prospects.

Ukraine is certainly not alone in having a dysfunctional, corrupted, fractured political establishment with a weak economy. In many ways, Argentina is a sister country for Ukraine. After decades of populism, divide-and-rule politics, the country has had every conceivable crisis: a default on public debt, banking crisis, currency crisis, nationalization of foreign-owned companies, protests on the streets, hyperinflation, economic depression, fights with the IMF and other international organizations, unstable governments, government property arrested abroad, etc. Most disturbingly, the key lesson from Argentina’s experience is that the mess can continue for a very long time, slowly — or sometimes quickly — bringing a country to its knees.

Fortunately, countries can overcome entrenched vested interests, modernize and get on a sustainable growth trajectory. Apart from having a major national security threat (e.g., Israel, South Korea, Taiwan), it helps to have an external anchor. The prospect of joining the EU was a key force to implement reforms, enforce changes, etc. in Poland, Hungary, Czech Republic and other eastern European countries. We have already seen that the potential of visa-free entry into the EU countries has been hugely helpful in overcoming resistance to anti-corruption efforts in Ukraine. In other words, weak domestic institutions can be strengthened by foreign institutions providing credible assurances that temporary disruption, discomfort and sacrifice will fruit in a better life in the future.

The IMF often plays a role similar to the EU’s: it serves as an enforcer in countries with weak institutions. The carrot of IMF loans incentivizes local elites to act together and implement reforms (demonopolization, privatization, deregulation, etc.). More recently the IMF became more insistent on implementing institutional reforms as a key condition to participate in the IMF programs to ensure that the fix is long-term and there is no going back. A country in crisis has little choice and thus has to comply to get funding, even if the IMF money brings a change in the balance of interests within the country. Equally importantly, the IMF gives a signal to foreign investors that a country is on the right track and is likely to improve in the future so that it’s a good time/place to invest.

The IMF is often portrayed by Ukrainian media and politicians as a “bad cop” but a better description is that the IMF is often a “doctor” that has to give a bitter pill to make a patient better off eventually. Some mistakes can happen — especially in complicated, chronic cases. For example, not all of us agree that taxing labor income of people receiving old-age pensions in a country with rapidly aging population is a good idea. Yet, most of the IMF requirements are hardly controversial. For instance, the energy subsidies that the Ukrainian government doled out to households were insane (Ukraine, which imports roughly 4/5th of its gas consumption needs, had gas tariffs for households lower than those in Russia from which it imported). This practice should have been stopped a long time ago, but it took a nearly fatal crisis and a subsequent IMF requirement to make it happen. Furthermore, while the IMF requirements may be not ideal, Ukraine’s leadership has rarely offered a better alternative.

This discussion should make it clear that the talks about cancelling a deal with the IMF is a bad idea.

First, Ukraine needs a lot of money to rebuild the economy and to cover short-term deficits. Ukraine’s economy may seem stabilized for now but the situation is still fragile. Ukraine needs external support and, at the moment, the key creditor is the IMF and the other international financial organisations that largely follow the IMF. Who else would give billions of dollars to the Ukrainian government at a reasonable price?

Second, Ukraine must build a reputation of a responsible business partner. It needs a good “credit history”. A history of a country that honors its commitments.

Third, Ukraine needs foreign expertise to enhance its institutions. The IMF can help with sharing its know-how in banking, foreign direct investment, macroprudential regulation, inflation targeting, etc.

Finally and most importantly, change in Ukraine can apparently happen only under the gun. Sometimes literally under the gun. A country with corrupt and entrenched elites needs an enforcer or an outside anchor to ensure that the interests of the public at large are set above the interests of the few in power. Ultimately, this role will be played by the civic society but currently the civic society is not mature enough to force politicians to resign in case of poor performance. It’s more likely that the government/parliament takes a “pill” in response to a threat of not receiving billions from the IMF than to an outrage of the public.

In summary, Ukraine is not in a position to risk a confrontation with the IMF. The IMF does not need Ukraine. It is Ukraine that badly needs all external support and expertise it can muster, including the IMF. VoxUkraine believes that it is critical to continue to cooperate with the IMF and meet the obligations on the program.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations