Post-revolutionary Ukraine has – after a long wait – embarked on the road to implementing much needed reforms that aim to tackle some deep-rooted systemic issues to do with anti-corruption, deregulation, public administration, banking, energy and health sectors. There are important strategic decisions to be made at many levels that will dramatically impact on the health, wellbeing and economy of the country and its people.

This article looks at how those strategic decisions are made, and more specifically, at the role research evidence has to play in those decision making processes. Ideally, one would think, decision makers would be wise to pay attention to what is already known about how to respond to particular problems, before they decide what to do. In responding to a significant health threat, for example, they might reasonably ask ‘what works’?

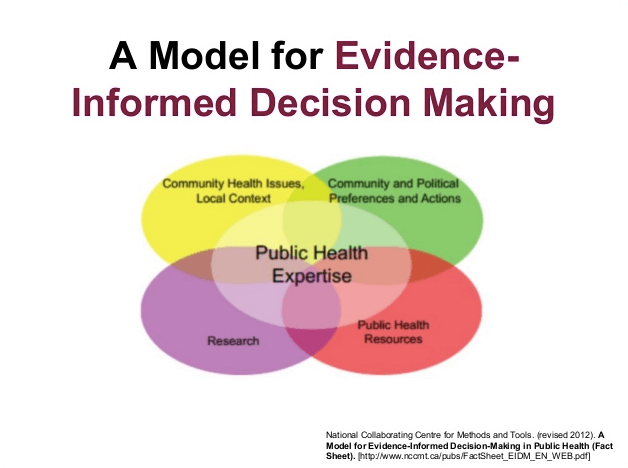

However, we know from a wealth of political science literature that decision making and policy processes are complex and messy rather than linear and rational. There are many reasons that lie behind the ever-present gap between what we know (about how to respond to a problematic situation) and what we do. Accordingly, the more rationalist assumptions of evidence-based policy making have been pushed aside by a call for evidence-informed policy making – that is, an attempt to ground strategic decision making in more reliable knowledge of ‘what works’ (Sanderson 2002). Evidence-based policy making adopts a “narrow, reductionist, and largely instrumental view of the relationship between evidence and policy”, derived from the model of evidence-based medicine (Hunter 2016). In contrast, evidence-informed policy making allows for a more nuanced view of this relationship and takes into account existing political and research cultures while also acknowledging that research evidence is only one factor influencing policy.

Scientific evidence often has a limited role in policy, with its uptake and impact depending on the significance of the issue on the policy agenda. The Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, in 2007 examined some of the reasons for this when they explored capacity issues and constraints within the evidence-informed policy-making process.

The ability of policy-makers to draw on appropriate evidence is often restricted by its availability. Our own recent research in Ukraine, which looked at the content, implementation and outcomes of key population health programmes, highlighted the poor quality and inaccessibility of data, and the paucity of much-needed research. There is currently no emphasis placed on developing a sound evidence base for policy through long-term impact evaluations of policies and programmes – something that Sanderson (2002) highlights as being crucial for ‘reflexive social learning’ and effective governance. The number of good research organisations in Ukraine that have the capacity to generate appropriate, trustworthy evidence, are few. In addition, those that exist – such as the Kyiv Economics Institute at the Kyiv School of Economics, or the Institute for Economic Research and Policy Consulting – struggle to get access to the data, or to have their findings understood and accepted by decision makers.

Finding common ground between policy-makers and academic researchers

We have already acknowledged that policy-making is complex, and that the path to evidence-informed policy-making is not rational. The academic research community has been slow to appreciate the complexity, relying instead on the ill-conceived notion that all they have to do is write up their evidence, and it will be incorporated into policy. In fact, they have contributed to some of the barriers to using evidence, which include:

- The complexity of the evidence, accompanied by arcane disputes over its methodological basis and rigour – what counts as evidence, and what evidence counts?

- The temporal challenge, whereby the time required to generate evidence exceeds the time policy-makers and managers are willing or able to wait before taking action

- A reluctance to explore ways of providing real-time evidence to inform policy and practice as it is occurring when its impact is likely to be most useful

- A failure to communicate and present messages and key findings in ways which policy-makers can understand and use in their work.

From the policy-makers’ point of view, they are driven by various impulses besides what the evidence may be telling them and advising them to do. These include:

- The intricacies and complexities of the policy process resulting in significant investment of time and effort to balance competing interests and reconcile the irreconcilable

- The ascendancy of political priorities when a government asserts it has a mandate from the electorate to drive through changes even if these fly in the face of the evidence

- Ideological acceptability even to a government that proclaims it is ideology-free and motivated by what works

- The multiple, and often contradictory and conflicting, goals of policy-makers, including direct opposition to the reforms by the incumbents, like at present in Ukraine

- A preference for tacit, experiential knowledge over research evidence

- A lack of consensus about the evidence and whose opinions count – the expert or the public?

The challenge facing both camps – researchers and policy makers – is how to reconcile their differences and overcome these barriers to find common purpose.

A useful starting point is for both sides to acknowledge the existence of complexity in the context of wicked problems that defy easy or single solutions. Both should endeavour to understand the nature of problematic situations, and to seek ways of improving those situations. Solutions to wicked problems will not be true or false but rather better or worse.

The centrality of politics in evidence-informed policy and implementation

The political nature of the policy process is critical to understanding complexity. Politics lie at the heart of public policy, however much we may deny it or wish it were otherwise. This is because in complex systems made up of multiple levels of decision-making and numerous groups of actors the interplay of power between these determines whatever outcomes emerge.

The political nature of the policy process is critical to understanding complexity. Politics lie at the heart of public policy, however much we may deny it or wish it were otherwise. This is because in complex systems made up of multiple levels of decision-making and numerous groups of actors the interplay of power between these determines whatever outcomes emerge.

It is why political science, often overlooked in such a context, can offer important insights into how policy does or does not succeed. The discipline deals with who gets what, when, and how. In settings where decisions are made about how to improve health, evidence is often invoked to justify prior decisions or make the case for political and financial support. Or it may be cited to justify inaction.

The multiple streams approach to thinking about public policy is useful in illuminating the messiness, power asymmetry and disjointed nature of policy-making (Kingdon, 1984). It does so through three streams that flow largely independently of one another: the problem stream (the nature of the problem, such as controlling smoking), the political stream (comprising the problems to be tackled, or not, by government), and the policy stream (the possible policy solutions to a problem from which to choose, such as introducing a ban on smoking in public places).

When these three streams are aligned and converge they create a so-called ‘policy window’ or ‘window of opportunity’ through which a public policy that might succeed can result.

Many of the core cleavages in public policy generally, and health policy in particular, reflect political and ethical tensions over the balance to be struck between personal and collective responsibility, public and private interests, and the rights of the community and personal freedoms. However these tensions get resolved, they entail intensely political choices.

Many of the core cleavages in public policy generally, and health policy in particular, reflect political and ethical tensions over the balance to be struck between personal and collective responsibility, public and private interests, and the rights of the community and personal freedoms.

To influence and shape health policy, it is necessary to understand the frameworks underlying policy-makers’ choices, the institutions with, and through, which governments operate, and the interests and positions of the different actors involved.

Problems of implementation often centre on a lack of political will and a failure to frame the problem in terms that the relevant policy-makers can comprehend and which may gain their interest and support. Only by re-politicising public policy will it be possible to bring about change.

Where next?

Arguably, policy still owes too much to political ideology and an absence of evidence. Even where sound evidence exists, it often lacks impact because researchers fail to ask the questions that matter to policy makers, present key findings in ways that are accessible to policy-makers, or work to timelines that are aligned with the needs of policy-makers.

The good news is that these realities and potential weaknesses are being addressed. More attention is being given to the importance of co-designing research so that it both meets the expressed needs of policy-makers and has their ownership of the outcomes which is likely to improve uptake. Collaboration with knowledge brokers and advocacy organisations is an important part of navigating the processes linking knowledge with policy. The Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research called this ‘evidence filtering and amplification’. It recognises that actors other than researchers have a role in picking out or filtering particular research outputs and translating them into policy messages, and in some cases amplifying them to try and influence policy-makers. In many spheres – including health policy – groups that play this role often have much more direct and stronger links to policy-makers than researchers (Sauerborn et al. 1999).

Collaboration with knowledge brokers and advocacy organisations is an important part of navigating the processes linking knowledge with policy. The Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research called this ‘evidence filtering and amplification’.

This approach underpins WHO’s new action plan to strengthen the use of evidence in policy-making. A key area for action is knowledge translation and increasing capacity in the journey from research to policy. The plan is committed to establishing a network of knowledge translation experts to support the dissemination and uptake of evidence for policy-making.

Taken together with other recent developments to assist knowledge translation, including the embedded researcher and researcher in residence experiments, the future for evidence-informed policy is looking more promising. However, can Ukraine benefit from these developments and what is needed to be done in health sector in this regard?

Recommendations for Ukraine

Short-term:

- computerise all the available data and make it available to researchers

- make all the government-funded research easily available to the public and decision makers

- commission translational research in areas which require urgent reforms from independent organisations and open the results to wider audience via a special platform (like EVIPNet or World of Labor)

- ensure access to international research databases on health and social research to researchers, students and practitioners in health sector

Long-term:

- educate high level and middle level health care authorities in modern health research methodology

- further develop e-Health system and ensure access to the data for researchers

- improve the skills of statisticians responsible for data analysis

- reform the system of public research funding from the institution-based to topic-based and open it up for competition from all qualified research teams

- introduce educational programmes in modern health research methods, including that in Health Economics.

Literatures

- Hunter, D., 2016, Evidence-informed policy: in praise of politics and political science, Public Health Panorama, 2(3):268-72.

- Kingdon, J. W., 1984, Agendas, Alternatives and Public Policies, Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

- Sanderson, I., 2002, Evaluation, policy learning and evidence-based policy making. Public Administration, 80:1–22.Sauerborn R., Nitayarumphong S, Gerhardus A (1999). Strategies to enhance the use of health systems research for health sector reform. Tropical Medicine and International Health, 4:827–835