How do geopolitical risks impact expectations of economic agents and economic forecasts? To answer this question, we look at both foreign and domestic geopolitical risks of 32 developed and developing countries.

There is a lot of research on the impact of geopolitical factors on macroeconomic variables but much less studies of their impact on economic expectations. Expectations are important because they drive decisions of households, firms, and policy-makers and thus impact future macroeconomic variables. Moreover, expectations provide rapid responses to the new information, which helps better understand the transmission mechanism of geopolitical risks, i.e. how wars or regime changes in one country affect welfare in other countries across the globe. Since shocks transmit internationally via global value chains, we look at the composition of trade of each country to see how foreign geopolitical risks may affect it.

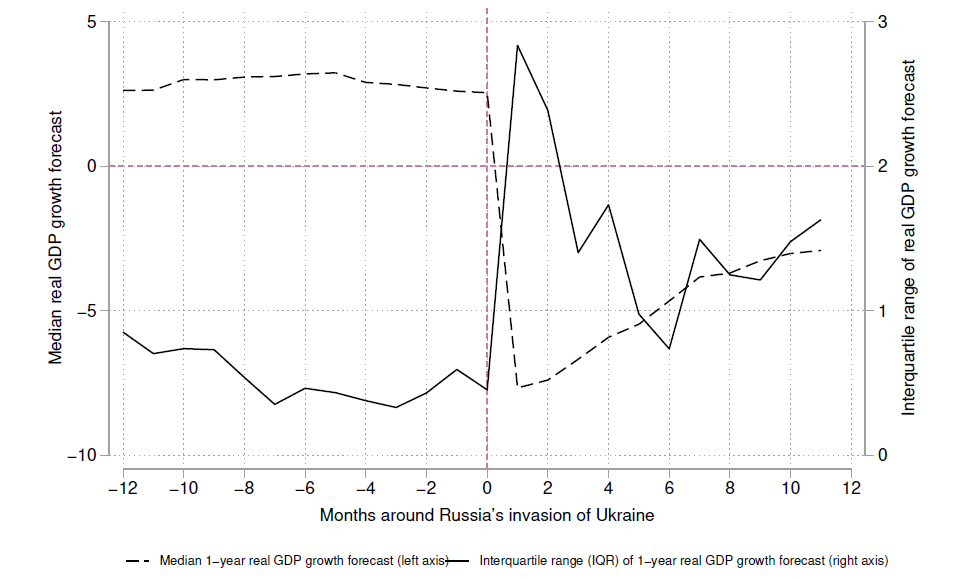

Figure 1 shows that almost immediately after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine real GDP growth forecast dropped (dashed line) while there was a huge spike in uncertainty of that forecast (solid line) and this uncertainty remains quite high. But is there a systematic impact of geopolitical risks on expectations or is this phenomenon specific to the current war and sanctions on Russia?

Figure 1. Median and interquartile range of GDP growth forecast

To answer this question, I look at how the consensus forecast of GDP and other macroeconomic variables produced by professional forecasters is affected by geopolitical risks. I look at both levels of the forecast and a measure of uncertainty of these forecasts for 32 countries (I use monthly data from January 1990 to June 2023).

I take an index of domestic geopolitical risks (GPR) from Caldara and Iacoviello (2022). This index is based on the news (i.e. it counts how often certain words, such as “war”, “conflict”, “revolt” etc. are mentioned by media in conjunction with certain countries or cities) and covers 44 advanced and emerging economies since 1985. Importantly, Caldara and Iacoveillo (2022) show this index to be exogenous to measures of macroeconomic uncertainty.

I construct my own measure of foreign geopolitical risk exposure based on bilateral trade volume. Foreign geopolitical risks index is the sum of a country’s volume of trade with all of its trading partners relative to its GDP weighted by domestic risks of trading partners. The idea is that if country A has a large volume of trade with country B, then domestic geopolitical risks of country B will largely affect macroeconomic variables of country A.

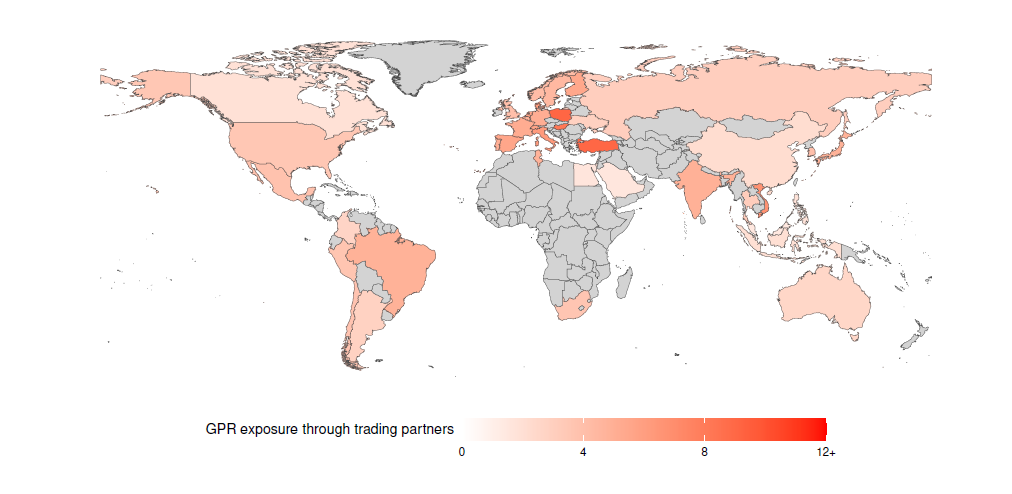

As Figure 2 shows, the foreign GPR index around Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 is higher for countries with tighter trade ties with Russia and Ukraine.

Figure 2. Foreign GPR index in 2022

Sources: Own calculations based on Caldara and Iacoviello (2022)

I also explore how the international transmission of geopolitical shocks depends on structural dimensions of trade. To do so, I construct measures of trade concentration as well as import and export elasticities at the product level for each country in my sample. The hypothesis is that countries with a more concentrated trade structure are more vulnerable to geopolitical shocks. Similarly, countries with more elastic exports and less elastic imports are more exposed to the adverse effects of such shocks.

To calculate export and import elasticities, I look at bilateral trade data and use product-level trade elasticities data produced by Fontagne et al (2022).

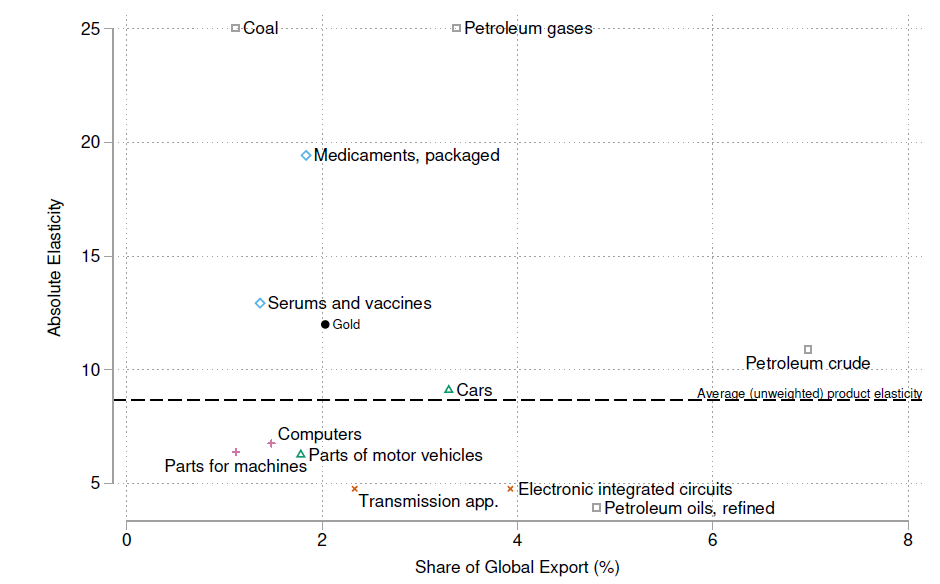

Figure 3 displays the substitution elasticity of the products that account for the largest shares of trade. For example, coal and petroleum gases are relatively easy to substitute, either because multiple sources of supply exist or because close alternatives are available. In contrast, products such as machine parts or computers are much harder to replace due to their complexity and the limited availability of substitutes. As a result, a country that primarily exports coal would exhibit higher export elasticity than one exporting advanced electronics or microchips. For instance, China displays high import elasticity, indicating that it can readily switch between sources of supply. However, its export elasticity is low, meaning that other countries find it difficult to substitute away from Chinese exports due to China’s dominant role in global supply chains.

Figure 3. Elasticity of selected products in global trade

I estimate the impact of domestic and foreign geopolitical risks on the median and interquartile range (a measure of dispersion) of forecasts, adding time and country fixed effects. I find that increases in both domestic and foreign geopolitical risks have limited impact on the level of forecasted GDP, consumption and inflation. However, such shocks systematically increase forecast uncertainty except for inflation.

Then, I re-estimate the model accounting for countries’ import and export base trade elasticities as well as trade concentration. I find that countries with low export elasticity, i.e. those whose exports are not easy to substitute, experience less forecast uncertainty when exposed to geopolitical shocks.

These findings have several policy implications. Governments should strengthen their capacity to assess and manage geopolitical shocks. They should also enhance policy communication to reduce uncertainty. Finally, diversifying trade linkages can enhance economic resilience.

The paper was presented during the 9th NBU research conference and can be found via the link.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations