In response to Russia’s seizure of Crimea in February 2014, the Atlantic Council launched a campaign to galvanize the transatlantic community into helping ensure that Ukraine survives as an independent nation. Ukraine must have a fair chance to build democracy and shape its own future, including, if it chooses, greater integration with Europe.

Post-Revolutionary Reform Agenda

By the time the democratic Maidan movement started in late 2013, Ukraine’s economic crisis was well under way. According to the World Bank, Ukraine entered economic recession in the second half of 2012[1]. The collapse of President Viktor Yanukovych’s corrupt regime in early 2014 left enormous challenges for the new leadership. The key question is not whether the country must implement reforms but rather where the government should start the process. After years of mismanagement, nearly every aspect of economic and political life in Ukraine needs reform. A recent poll[2] of experts (prominent economists, political scientists, lawyers) conducted by VoxUkraine, a civil society organization, identified five areas as the most pressing: persistent corruption, inefficient energy sector, excessive regulation, civil service bureaucracy, and a mismanaged financial sector.

- Corruption. By nearly every metric, Ukraine has one of the worst corruption problems in the world. Eliminating corruption would provide a boost for the economy, ensuring better provision of public services and creating a foundation for efficient implementation of other reforms. Almost 40 percent of surveyed experts noted anti-corruption reforms should be a subset of broader reforms of the judiciary system and law enforcement prosecution agencies strengthening the rule of law in Ukraine.

- Energy sector. Ukraine’s energy sector is grossly inefficient. The government spent billions of dollars supporting unprofitable coal mines and subsidizing gas prices for households and firms [3] [4]. This practice not only placed unsustainable pressure on public finances but also resulted in glaring inefficiencies in energy use. Furthermore, the lack of diversification in energy supplies made Ukraine’s economy vulnerable to blackmail by Russia’s state-owned energy giant Gazprom and created a monopolized market for energy, feeding corruption and rent-seeking.

- Regulation. The business environment in Ukraine was plagued by regulation, onerous taxation levels and administration, and concentration of market power. The World Bank’s 2014 Ease of Doing Business ranking (covering regulations measured from mid-2012 to mid-2013, the last year of Yanukovych’s presidency) ranks Ukraine 112th out of 189 countries surveyed[5]. Liberalizing economic life by cutting red tape, simplifying tax administration, and opening markets for more competition is essential for boosting private entrepreneurship and thus providing people with opportunities to take care of themselves instead of relying on state support.

- Excessive bureaucracy. After years of poor pay, cronyism, and political appointments, the civil service is bloated and largely discredited in the eyes of the public. Many Ukrainians see government officials as corrupt and incompetent. In 2013 (the last year of Yanukovych’s presidency), Ukraine ranked 148th in Government Effectiveness Index compiled by the World Bank [6]. To ensure reforms are not sabotaged or reversed by discredited incumbents, civil service reforms should not only concentrate on attracting a critical mass of new blood into the government at all levels but also create conditions for sustaining a small, skilled, and honest bureaucracy. Selection criteria and processes for both hiring and promotion should be transparent and based on merit. The salaries must be competitive. Finally, decentralization of political power to local governments will increase public officials’ accountability to the people.

- Financial sector. Poor macroeconomic policies resulted in volatile business conditions that hampered investment, destabilized the financial sector, and led to frivolous redistribution. For example, the adoption of a fixed-exchange rate regime was a major cause of multiple banking and currency crises as well as high and unpredictable inflation. Macroeconomic stabilization is essential for resuming economic growth. Better monetary and fiscal policies such as inflation targeting, a flexible exchange rate regime, program-based public funding, and the establishment of an independent Central Bank, can radically reduce uncertainty, improve allocation of resources, and stimulate growth.

Of course, this list is far from complete; however, these reforms catalyze subsequent rounds of economic restructuring and place the country on a path to robust economic growth. The new government appreciates the vital importance of addressing extraordinary challenges in these areas. The current political leadership— including President Petro Poroshenko, Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk, and Speaker of the Parliament Volodymyr Groysman—pledged to fight corruption, secure stable energy supplies at market prices, cut red tape, simplify taxation, stimulate competition, overhaul civil service, decentralize the government, and ensure macroeconomic stability. Ukraine has a herculeanan task before it and needs international assistance to survive this crisis.

The Role of the International Community

The international community is providing important political and financial support to post-revolutionary Ukraine. In February 2015, international financial institutions (IFIs) and individual countries agreed on an approximately $40 billion four-year financial support package for Ukraine’s $132 billion economy,[7] following an estimated $10 billion loan disbursed in 2014 in the framework of a previous support package approved in early 2014. The 2015-18 package includes $17.5 billion Extended Fund Facility from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), [8] a deeper and longer stabilization program than a typical stand-by agreement provided by the Fund.

More than $7 billion is supposed to come from other IFIs and individual countries including the World Bank, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), the European Investment Bank (EIB), the United States, the European Union (EU), Japan, and others. Another $15 billion is expected to be raised through the restructuring of Ukraine’s sovereign and quasi-sovereign debt held by private creditors [9]. Ukraine’s post-revolutionary leadership can count on more than $50 billion in support from the international community over five years to stabilize the economy, implement reforms, and return the country to growth. This package is much less generous than what Greece received during the debt crisis, leading some analysts to argue that Ukraine should have received more from its allies. But one should bear in mind that Ukraine’s record with meeting the requirements of previous IMF programs has been quite poor. Out of the nine IMF bailout programs that Ukraine received since its independence, only one (signed in 1996) was fully completed. Although the current reform-oriented government could mean that this bailout will be different, it would be risky to flood the country with cheap money before the country does more to combat corruption. Thus, the cautious approach of IFIs with respect to the funding amount and disbursement schedule is not groundless.

Importantly, almost each dollar from the support package is tied to implementation of specific steps in the reform process. The IMF has taken the lead in assigning conditionality to funding. Numerous conditions attached to the IMF program can be split into two categories: (1) stabilization measures; (2) structural reforms. The former includes a typical set of economic policy measures such as fiscal consolidation, continuing transition to a flexible exchange rate regime accompanied by prudent monetary policy, and banking system rehabilitation. The structural reforms include strengthening the Central Bank’s independence; overhauling weak banking system supervision; reforming the pension, healthcare, education, and social assistance systems; improving the tax revenue administration; and reforming the loss-making and opaque gas sector.

The IMF pays special attention to Ukraine’s deeprooted problems of poor governance and widespread corruption. Back in mid-2014, the Fund’s experts conducted a diagnostic study [10] of governance issues that focused on three areas: corruption (especially at high levels), regulatory regime, and effectiveness of the judiciary. Based on the recommendations of the study, Ukraine’s authorities committed to establish an independent National Anti-Corruption Bureau (NAB) empowered to investigate high-level officials, strengthen anti-money laundering legislation, and improve asset disclosure procedures. State-owned enterprises (SOEs) were identified as key sources of corruption and inefficiency[11]. SOE reform became another important objective of the IMF agenda.

The requirements of other IFIs supplement the IMF’s efforts in Ukraine. In particular, the World Bank prioritizes the efficiency of public expenditures including the quality of state investment projects and banking system rehabilitation procedures. EU macro-financial assistance targets improvements in public administration, transparency, and public finance management.

Reform Progress Unnoticed by the Public

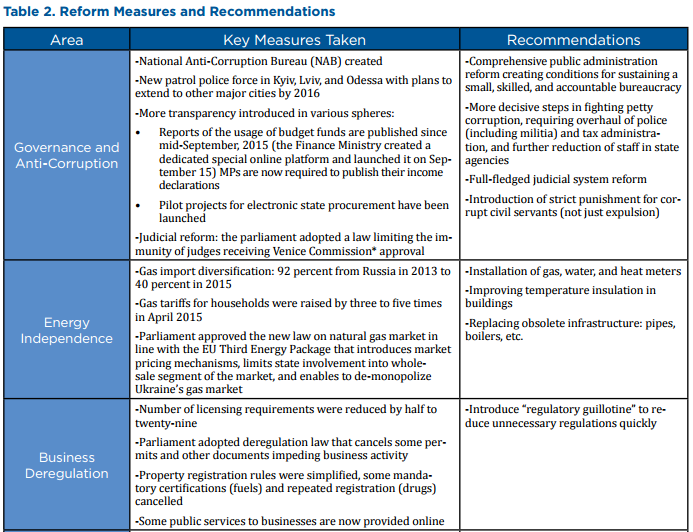

Are any reforms taking place? The answer is yes, at least in the eyes of experts. VoxUkraine has monitored the progress of economic reforms in five key areas— anti-corruption & governance, public finance, business regulation, financial markets, and energy sector—since early 2015. Together with partner institutions and a pool of more than thirty experts, VoxUkraine asseses the speed and quality of reforms, scoring progress from -5 to +5 [12]. The resulting Reform Index has never slipped into negative territory. However, Reform Index rarely rose to the level of +2, which would signal an “acceptable pace of reforms”[13]. The major reform steps identified by the team of experts include a substantial and long-overdue 285 percent hike in domestic gas tariffs; approval of the legislation facilitating a clean-up of the banking system; and adoption of the new gas market law in line with European practices. All three of these reforms are required by the IMF program. The experts also positively assessed the law deregulating business environment, increased transparency in public procurement and government’s decision to liquidate Ukrecoresurs, a waste disposal company widely known as one of the most corrupt state-owned enterprises.

National Bank of Ukraine. Kyiv, Ukraine. Photo: Alexander Noskin

At the same time, businesses and Ukrainian citizens seem to feel little if any improvement. The Investment Attractiveness Index compiled by the European Business Association, a community of more than nine hundred Ukrainian and international companies, was 2.66 points in the second quarter of 2015 out of a 5.0 maximum [14]. This is much better than the 1.8 points at the end of 2013 when the street protests began, but only marginally higher than the average 2.2 points observed in 2011- 13 during the Yanukovych years. Results of another poll [15] conducted in February-March 2015 by a group of international and local organizations suggest that only 15 percent of businesses see some decline in corruption, while 57 percent consider corruption at the same level as half-year ago and 28 percent perceive it as growing.

Anti-Corruption Efforts

National Anti-Corruption Bureau Political corruption has plagued Ukraine for years with influential oligarchs and their political allies routinely colluding to defraud taxpayers and stonewall much needed reforms. Despite pressure from the public and the international community, many in the country’s elite continue to derail reform attempts. In this atmosphere, the stakes are high for the newly established National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine, which is tasked with rooting out high-level corruption.

NAB’s formation, encouraged by the IMF, was and continues to be a major undertaking involving the coordinated efforts of government and civil society. Although beset by delays, the agency now has a director, permanent offices in Kyiv, a publicly elected civil society oversight committee, and it has hired its first detectives [16]. In addition, the agency’s employees will be among the highest paid civil servants in the Ukrainian government, a move designed to attract high quality candidates and insulate them from corrupting influences.

NAB’s success will hinge on the effectiveness of two other newly formed units: the National Agency for Prevention of Corruption (NAPC) and the Specialized Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office. NAPC will audit the income and asset declarations of politicians and civil servants for corruption indicators and help set the country’s corruption fighting agenda. The Specialized Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office will act as NAB’s enforcement arm, allowing detectives to initiate criminal cases against high-level officials suspected of corruption.

So far, NAB has met surprisingly little direct political resistance, which is due in large part to the agency’s high domestic and international profile. Instead, entrenched political interests are focusing their efforts on foiling NAB’s mission by undermining the lower profile partners, on which it depends. A recent lawsuit by Transparency International Ukraine alleged that the Cabinet of Ministers circumvented the law to control the process of vetting and appointing the NAPC’s management team [17]. Meanwhile, the wellrespected Anti-Corruption Action Centre claimed that the President’s party was attempting to control the selection of the head of the Specialized Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office[18].

The rapid response of Ukraine’s civil society and assistance from the international community appears to have paved the way for a fair and transparent selection process in both cases [19][20]. In spite of that success, NAB, the NAPC, and the Specialized Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office will remain vulnerable to political meddling. The complicated structure of the new anti-corruption apparatus and the technical nature of political meddling make each new threat challenging to communicate to the public and to effectively counter in the media.

Despite the continued challenges, NAB remains the face of the anti-corruption fight in Ukraine. The longterm success of this effort will hinge on the continued vigilance of Ukraine’s civil society, the ongoing support of the international community, and persistent efforts to inform the Ukrainian public.

Tangible Reform for Citizens

While international lending institutions, donors, and politicians focus on solving high-level corruption, the often incremental and complex changes can be hard to see and feel for ordinary Ukrainians. This is why the recent overhaul of the patrol police in several large cities, including Kyiv, has been a breath of fresh air for Ukraine and is giving hope for locally meaningful reform.

Ukraine’s police force is notoriously corrupt and is perhaps best known for its officers soliciting petty bribes during routine traffic stops. But in January 2015, Ukraine’s Ministry of the Interior began the process of recruiting two thousand new patrol police officers for the city of Kyiv[21]. The rigorous selection process included a battery of tests and a three-month training program conducted with the help of American police officers. The stringent criteria, coupled with relatively high salaries (approximately three times those of the former police force), should act as a bulwark against a culture of corruption[22].

Kyiv’s new officers took to the streets on July 4, 2015, and are enjoying widespread approval from city residents[23]. Since then, new police forces also began work in Lviv and Odesa with plans underway to expand the new policing model to other regions of Ukraine.

Mixed Progress Overall

While progress has been made in establishing a national anti-corruption apparatus, conducting moderate tariff reforms, and changing state procurement guidelines, support for these changes among the political elite remains tepid at best. Instead of pursuing a systematic reform agenda to tackle a broken civil service, a corrupt judiciary, and a suspect state prosecution function, politicians have adopted a reactionary strategy. They too often rely on outside pressure from Ukraine’s active civil society and the international community to drive the country’s reforms. Until political will is generated from within the ranks of influential politicians, the pace of reforms will continue to be predictably slow and the scope of those reforms narrow.

Progress on Other Core Areas

Energy Sector

The Ukrainian government has always been very involved in the energy sector because of its vital importance to the economy. All previous governments kept energy tariffs low and covered the deficit of the state-owned oil and gas monopoly Naftogaz from the state budget. This was a costly policy: in 2014, for example, Naftogaz’s deficit exceeded the total government deficit[24].

As a first step toward market reform in the energy sector, the authorities diversified gas imports away from Russia and toward the reverse flows from the EU. 74 percent of imported gas came from Russia in 2014 as compared to 92 percent in 2013[25]. This year, gas supply from the northern neighbor is expected to drop to 40 percent and may fall to zero next year [26]. In April 2015, the government raised gas tariffs for the population by three to five times [27] —a very unpopular step the previous governments did not dare to make.

Almost simultaneously, the parliament approved two regulations essential for energy market reform: the law “On natural gas market,”[28] which introduces principles of the EU Third Energy Package, and two additional laws[29] allowing energy service companies to implement energy efficiency (modernization) projects.

These first steps in the energy sector reform, although very important, are relatively easy to make. Further measures, including installation of millions of energy meters, improving energy efficiency of millions of houses, and updating millions of kilometers of obsolete infrastructure, will be more lengthy and costly to implement.

Deregulation

Deregulation is perhaps the most powerful tool for fighting corruption in Ukraine. Since corruption is systemic rather than episodic, many regulations exist merely to provide a “job” of issuing some licenses, permits, etc., for some state bodies or officials (and extracting rents for performing these unneeded services).

For the last year and a half, several laws aimed at deregulation and reduction of the number of licenses, certificates etc. were adopted. In March 2015, the Ministry of the Economy and Trade developed a detailed deregulation plan for 2015 foreseeing further deregulation for all industries[30].

By the end of 2015, the government plans to adopt a “regulatory guillotine” eliminating excessive regulations. There are numerous examples of small excessive regulations that make it difficult to run business in Ukraine.

For instance, now a special permit is required to use the equipment producing food for children, though all food products should anyway meet quality standards. These and similarly unnecessary permits and licenses are going to be cancelled. Also, a few initial steps toward e-government, such as an electronic property register or online service of the Ministry of Justice, already lowered transaction cost for individuals and business entities.

Taking into account the determination of the government to liberalize the economy, this process— although somewhat sporadic—will be successful. One should not expect, however, cancelling of all licences, permits, and certificates. For the most part, Ukraine will replace its own regulation with the EU’s within the framework of the Association Agreement. A lot of this work will relate to introducing EU standards for consumer products replacing outdated Ukrainian standards, largely inherited from Soviet times.

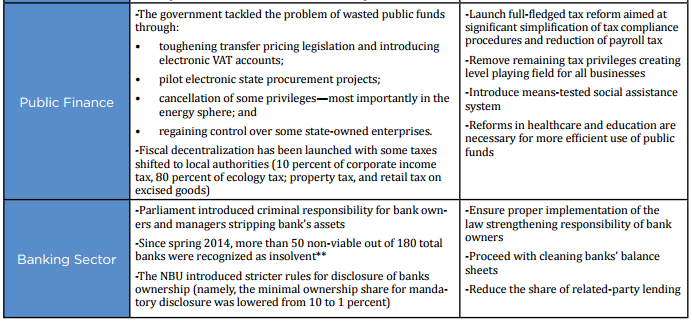

Public Finance

Ukrainian government redistributes over half of the country GDP, and a large share of public funds is wasted. The three most important channels of wasting the money are public procurement; the categorical system of privileges (public support given to a class of citizens— e.g., everybody with a child—rather than means-tested); and large-scale tax evasion caused by high compliance cost and selective enforcement.

Reforms in the fiscal sector tried to address these problems. To reduce fraud and waste in public procurement, the government introduced pilot projects of electronic state procurement expanding it to all government purchases until the end 2016. Authorities also approved legislation enabling international organizational involvement in medical drugs procurement, which has been known as one of the most corrupt spheres[31]. The Ministry of infrastructure opened the data on all procurement of subordinate enterprises and initiated online broadcasting of tenders. Also, since September 1, 2015, all government bodies have to disclose public funds use in much more detail than they do now.

Attempts to reform the system of privileges included cancelling some of them (e.g., free public transportation for students) and making others dependent on income (e.g., 50 percent discount on utility tariffs for families with more than three children). However, a meanstested social safety net is only at the discussion stage. This will be one of the biggest challenges.

* Venice Commission at the Council of Europe is an independent body of legal experts that can review (draft) legislation and provide comments on whether it is in line with the best legal practices and the main principles of EU legislation. See http://www.venice.coe.int/webforms/events/

** IMF, Ukraine, IMF country report no. 15/218, op. cit

Finally, the government tried to raise budget revenues by reducing opportunities for tax evasion through transfer pricing and by regaining operating control over some state-owned enterprises, which have been for years controlled by oligarchs.

Two reforms the government is most proud of are the tax reform and fiscal decentralization. While the latter can be considered a genuine reform leading to increased revenues of local communities, the former was mostly merging some taxes while keeping the overall tax rate at the previous level. Currently, with the help of NGOs and international experts, the Ukrainian government is developing a real tax reform.

Banking Sector

A well-functioning financial system is crucial for a healthy economy, and the National Bank of Ukraine (NBU) is doing a good job in restoring the functionality of the banking system. As a part of the “IMF package,” the Ukrainian government adopted a law increasing bank owner responsibility. It prescribes criminal responsibility for stripping of a bank’s assets and transferring liabilities to the State Deposit Guarantee Fund (or the state budget)—this has been a widespread scheme of bank fraud. Since spring 2014, more than 50 non-viable banks out of 180 total banks have been recognized as insolvent; however, none of their owners has been held responsible for emptying the bank’s assets in accordance with the new law.

Besides “killing” the bad banks, the NBU is ensuring the future health of the banking system by introducing stricter rules for disclosure of information on bank ownership and related party lending, and raising reputational requirements for banks’ owners and CEOs.

Conclusion

Ukrainian authorities are moving forward with reforms in various areas. The most prominent achievements are the establishment of the National Anti-Corruption Bureau to fight high-level corruption, the introduction of a new police force in the cities of Kyiv, Odesa, and Lviv, the reform of the banking system, and the restructuring of the natural gas sector.

However, these reforms are still insufficient given the vast reform agenda Ukraine’s authorities face. Apart from a new police force in Kyiv and a handful of other cities, there were few attempts to reform the civil service. Businesses continue to claim that middleand low-level employees at tax and customs agencies remain corrupt. The central government is significantly overstaffed, inefficient, and employees are unmotivated. The government’s decision-making process is often ineffective and impedes the successful implementation of reforms.

The international support package provides an incentive to reform in critical areas. Many of the requirements have been met, but requirements of the IMF and other international organizations represent only a critical minimum in reforms the country needs to implement. It is in the interest of Ukraine’s leadership to progress with reforms faster than prescribed by the IMF and others.

If the Ukrainian government does not follow through with an ambitious reform agenda, public support for reforms will wane while dissatisfaction will increase, threatening political stability and the country’s successful future. There is no time for slow evolutionary changes. Radical and revolutionary reforms are the only way to success.

on the Atlantic Council

Notes

[1] World Bank, “Ukraine Economic Update—April 2013,” http://www. worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2013/04/02/ukraine-economicupdate.

[2] Editorial board of VoxUkraine, “Reform Priorities: Expert Survey Results,” September 15, 2014, https://voxukraine.org//2014/09/15/ reform-priorities-expert-survey-results/.

[3] VoxUkraine editorial board, “DNR/LNR: Creative Destruction,” December 3, 2014, https://voxukraine.org//2014/12/03/dnrlnr-creativedestruction/.

[4] According to the IMF, gas and heating subsidies accounted for 7-8 percent of Ukraine’s GDP in 2012-14. See IMF, Ukraine, IMF country report no. 15/69 (March 2015), http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/ scr/2015/cr1569.pdf

[5] World Bank, Doing Business 2014: Understanding Regulations for Small and Medium-Size Enterprises (October 29, 2013), http://www. doingbusiness.org/reports/global-reports/doing-business-2014.

[6] World Bank, Worldwide Governance Indicators, http://info. worldbank.org/governance/wgi/index.aspx#home.

[7] Daryna Krasnolutska, Volodymyr Verbyany, and Mark Deen, “Ukraine Gets IMF-Led $40 Billion Aid Accord to Avert Default,” Bloomberg, February 12, 2015, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/ articles/2015-02-12/imf-chief-announces-ukraine-aid-extension-toabout-40-billion.

[8] IMF, “IMF Executive Board Approves 4-Year US$17.5 Billion Extended Fund Facility for Ukraine, US $5 Billion for Immediate Disbursement,” March 11, 2015, http://www.imf.org/external/np/sec/pr/2015/ pr15107.htm.

[9] IMF, Ukraine, IMF country report no. 15/69, op. cit.

[10] IMF, “IMF Executive Board Approves 4-Year US$17.5 Billion Extended Fund Facility for Ukraine, US$5 Billion for Immediate Disbursement,” March 11, 2015, http://www.imf.org/external/np/sec/pr/2015/ pr15107.htm.

[11] According to IMF estimates, SOEs received 2.5 percent of GDP of transfers from the government in 2014, while they generated only 0.2 percent of dividends. See IMF, Ukraine, IMF country report no. 15/69, op. cit., p.33.

[12] The pool of experts is surveyed every two weeks. Experts evaluate legislative acts that were adopted over the period on a scale from -5 to +5. Based on individual legislation they also evaluate reform progress, or lack thereof, in key five areas. Score +5/-5 is given to a legislation that (upon its successful implementation) would radically change rule of the games in one or several areas or significantly affect behavior of many economic agents. Same score for an area means that important legislation leading to significant positive (or negative) changes was adopted in this area. The aggregated experts’ scores for each of the five areas are averaged to receive Index value.

[13] The methodology implies that Reform Index can reach a high value of above +4 only if radical and deep reforms are taking place in all five areas. As this is hardly realistic to expect on a biweekly basis, authors of the Index use value of +2 as threshold for the acceptable pace of reforms.

[14] European Business Association, EBA Investment Attractiveness Index, 2nd Quarter, http://eba.com.ua/static/indices/iai/Index_28_ eng_2015.pdf.

[15] CEOs of 2,741 enterprise were surveyed by GfK, Transparency International, PWC, and PrivatBank. See http://corruption-index.org.ua/ (in Ukrainian).

[16] National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine, August 26, 2015, http:// www.nabu.gov.ua/index.php?id=6 (in Ukrainian).

[17] Transparency International Ukraine, “Government of Ukraine Manipulated Composition of the Panel That Will Select Members of the National Corruption Prevention Agency,” June 10, 2015, http://tiukraine.org/en/news/oficial/5314.html.

[18] Daryna Kalenyuk, “Poroshenko Attempts to Control Anti-Corruption Investigation and Prosecution,” Kyiv Post, June 5, 2015.

[19] Anti-Corruption Action Centre, “Civil Society and the Members of Parliament Presented Candidates to the Selection Commission on Anti-Corruption Prosecutor,” August 28, 2015, http://antac.org. ua/en/2015/08/civil-society-and-the-members-of-parliamentpresented-candidates-to-the-selection-commission-on-anti-corruptionprosecutor/.

[20] Transparency International Ukraine, “If the Government Complies with the Decision on Open Formation of the National Agency for Corruption Prevention, TI Ukraine Will Withdraw Its Claim,” August 13, 2015, http://ti-ukraine.org/en/news/5454.html.

[21] Anastasia Forina, “New Patrol Police Service to Replace Traffic Police in Kyiv in July,” Kyiv Post, January 19,2015, http://www.kyivpost.com/ content/ukraine/new-road-patrol-service-to-replace-traffic-police-inkyiv-in-july-377788.html.

[22] Laura Mills, “In Ukraine’s Capital, a New Show of Force,” Wall Street Journal, August 6, 2015, http://www.wsj.com/articles/in-ukrainescapital-a-new-show-of-force-1438903782.

[23] Roman Olearchyk, “Kiev’s Revamped Police Force Takes to Streets to Rebuild Trust,” Financial Times, August 17, 2015, http://www.ft.com/ cms/s/0/f895cef8-4032-11e5-9abe-5b335da3a90e.html#axzz3jCfIjczo.

[24] According to the IMF, Naftogaz’s deficit reached 5.6 percent of GDP in 2014, exceeding general government deficit of 4.5 percent of GDP. See IMF, Ukraine, IMF country report no. 15/218 (August 2015), http:// www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2015/cr15218.pdf.

[25] Naftogaz, http://www.naftogaz.com/www/3/nakweb.nsf (in Ukrainian).

[26] According to Naftogaz head Andriy Kobolev. See Ukrayinska Pravda, http://www.pravda.com.ua/news/2015/03/12/7061206/ (in Ukrainian).

[27] New gas tariffs set by the National Commission for Regulation of Energy and Communal services: gas tariffs for population, http://www.nerc.gov. ua/?id=14329 (in Ukrainian); gas tariffs for heating companies; gas tariffs for heating companies, http://www.nerc.gov.ua/index.php?id=14139 (in Ukrainian); electricity tariffs for population, http://www.nerc.gov.ua/index. php?id=14359 (in Ukrainian). The agreement between the IMF and Ukraine foresees raising gas tariffs for population to the market level by April 2017. See IMF, Ukraine, IMF country report no. 15/69, op. cit.

[28] Vekhovna Rada of Ukaine, http://zakon2.rada.gov.ua/laws/ show/329-viii (in Ukrainian).

[29] Vekhovna Rada of Ukaine, http://zakon4.rada.gov.ua/laws/ show/327-viii (in Ukrainian); Vekhovna Rada of Ukaine, http://zakon2. rada.gov.ua/laws/show/328-viii (in Ukrainian).

[30] Vekhovna Rada of Ukaine, http://zakon4.rada.gov.ua/laws/ show/357-2015-%D1%80 (in Ukrainian).

[31] The respective law was approved in March 2015. However, it has not been implemented as of August 2015. See Patients of Ukraine, http://patients.org.ua/2015/08/05/zakupivlyam-likiv-i-vaktsincherez-mizhnarodni-organizatsiyi-buti-vzhe-tsogo-roku-v-ukrayini/ (in Ukrainian).

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations