Startups are powerful engines for economic growth—driving innovation, creating jobs, and boosting global competitiveness. Countries that nurture startups can transform their entire industries and rapidly increase output. Yet, building a thriving startup ecosystem is challenging, and many nations struggle to unlock its full potential. Ukraine is currently at a turning point: with one of the fastest-growing start-up ecosystems in Europe, it has a real chance to follow in the footsteps of Estonia (the European leader in terms of the number of unicorns per capita) and the United States (the global benchmark). In this article, we explore the question: what lessons can Ukraine learn from the experience of these leaders?

The worldwide startup environment in 2025 encompasses approximately 594 million entrepreneurs operating across diverse markets, with 305 million new ventures created annually. This translates to over 800,000 new businesses launched daily, out of which 137,000 are startups, which reflects unprecedented global entrepreneurial activity.

According to Alex Wilheim’s 50-100-500 Rule, a startup stops being a startup when the business hits $50 million in revenue or employs 100+ people or has a valuation of $500+ million. This dynamism comes with sobering realities: on average, 90% of venture capital-backed startups fail, with 10% failing within the first year and 70% disappearing within the first decade. In some countries the situation is better: for example, in the US startup failure rate is 80% while in Estonia it drops to 75%.

Alongside high failure rates, successful startups have disproportionate economic impact. The total market value of startups globally surpassed $6.4 trillion in 2022—close to the combined annual GDP of Germany and Canada ($6.92 trillion), with global Unicorns (companies valued at over $1 billion) contributing 87.5 % of total value (note however that market value of a firm does not necessarily transform into profitability).

Globally there are over 1,245 unicorn companies with the US leading with 611 active unicorns created between 2020-2023, followed by China (146), India (67), and the UK (52). However, when adjusted for population, smaller innovation-focused economies dominate: Israel leads with 5.6 unicorns per million people, followed by Estonia (3.0), and Singapore (2.4).

According to StartupBlink, the global startup ecosystem is evaluated across three main components: Quantity (the level of startup activity), Quality (the impact and success of ecosystem activities), and Business Environment (how supportive the conditions are for startup growth). In 2025, the ecosystem’s overall growth rate is just below 21% (April 2025 to April 2024), reflecting increases in activity, success, and supportive conditions worldwide.

Different regions showed different growth rates: Asia Pacific had the highest rate of 27.4% followed by Europe with 26.2%, while North America had the slowest growth rate of 15.7%. The fastest growing ecosystem was in the Foodtech industry (46.1%), followed by Hardware & IoT of 45.4%, while EdTeach declined by 2.3%.

Now let’s focus on three countries: the US, which is a global leader on the startup scene, Estonia, that has the second-highest unicorn per capita rate in the world and highest annual ecosystem growth in Europe of 34%, and Ukraine who has unprecedented growth of 26.2% during such turbulent times. Table 1 provides some macroeconomic comparison between these countries.

Table 1. Selected macroeconomic and startup indicators for the US, Estonia, and Ukraine

| Indicator | US | Estonia | Ukraine |

| Gross Domestic Product (nominal, US dollars), 2024 | 29.18 trillion | 42.76 billion | 190.7 billion |

| Gross Domestic Product per Person (US dollars), 2024 | $84,475.26 | $31420.86 | $5036.94 |

| Average Annual Gross Domestic Product Growth Rate (percent), 2014 – 2024, Woldbank data | 2.74 | 1.86 | -2.92 |

| Average Annual Inflation Rate (percent), 2014-2024 | 3.20 | 4.50 | 15.96 |

| Average National Unemployment Rate (percent), 2014-2024 | 4.94 | 6.93 | 13.0 |

| Purchasing Power Index, 2014-2024 average | 120.91 | 69.05 | 32.23 |

| Cost of living index, 2014-2024 average | 72.9 | 53.0 | 28.59 |

| National Population (number of people), 2024 | 345,426,571 | 1,360,546 | 37,860,221 |

| Total Number of Startups | 1,232,265 | 1,452 | 2,600 |

| Number of Startups per One Million People | 3,308 | 1,067 | 4.2 |

| Global Startup Ecosystem Ranking (2025) | 1st | 11th | 42nd |

| Annual Startup Ecosystem Growth Rate (percent, 2025) | 18.2 | 34.0 | 26.2 |

Sources of the numbers in the table are provided as hyperlinks. They include World Bank, macrotrends.net, nimbeo.com, tracxn.com, u.ventures, and investinestonia.com. Note that some sources, e.g. Forbes, provide much lower estimates of Ukraine’s population – at about 30 million people. However, since no official data is published, we stick to estimates available in the international sources: macrotrends, worldometer, tradingeconomics.

The US currently holds the highest position in global ranking according to StartupBlink. It has the most developed economy, the largest population of the three countries, and the highest startup rate per million people. Estonia, however, leads in the rate of unicorn creation per year. It is on the upward trajectory for the second year in a row, moving up one place to 11th in the world. It is now on the verge of entering the global top 10, with a gap of less than 1% in score compared to the Netherlands (10th). Estonia’s population‑adjusted ecosystem growth rate exceeds 34%, enabling it to surpass Australia (12th).

Ukraine, ranked 42nd globally, has the highest ecosystem growth rate (26.22%) among countries in the 41st–50th range. Ukraine’s neighbors in this ranking are Bulgaria (41st) declining four spots due to a mild ecosystem decline, and Mexico (43rd place) since its ecosystem growth rate below 5% pushed it down by two steps. Despite severe challenges in recent years due to the ongoing war—including a sharp GDP drop of 28.76% in 2022—Ukraine has begun to stabilize. Since 2023, its economy has shown an average annual growth rate of 4%. Its unemployment rate, which skyrocketed in 2022 to 24.5%, in 2023 declined to 19.05% and in 2024 to 14%, which is still 5 p.p. higher than in 2021.

Despite the slowdown and largely due to military innovation, Ukraine’s startup ecosystem is very dynamic. Ukraine has four cities in the global top 1000 entrepreneurial city ranking, although every city except the capital, Kyiv, is experiencing a decline in 2025. Despite that, Ukraine continues to climb in Eastern Europe Global Startup Ecosystem Ranking, moving up one spot to reach 8th place, overtaking Romania. Ukraine ranks second in Eastern Europe and 17th globally in the SaaS industry.

Why are startups important for a country? As we discuss next, startups increase productivity and create workplaces, they support competition and increase the competitive advantage of the entire economy.

Startups increase employment and productivity

The US is the biggest startup economy incubator. Even though young innovative enterprises create only 5% of the total number of jobs there, they provide 15% of total aggregate employment growth, which directly affects economic growth.

The explanation behind startups’ substantial contribution to employment growth lies in the center of the startup business model, which is strongly defined by the so-called “up-or-out” dynamics. This principle means that startups need to grow and expand rapidly, thus hiring more staff, or fail and exit the market. This is conditioned by financial realities: young and small enterprises are usually considered as highly risky investments and therefore receive limited funding in stages, known as investment rounds. To secure the next round of funding, startups must demonstrate significant progress in growth or expansion. This growth should justify investor trust and reduce perceived risk, which on a general scale makes a large contribution to total aggregate employment growth.

The data shows that small firms create most jobs and employ the majority of people. A study of firm size and job creation shows that the relationship between a firm’s growth and its size breaks when controlling for the firm age. In other words, startups, with their “up-or-out” dynamics, make an important contribution to economic growth. Although the majority of startups fail, as discussed above, they still provide valuable contributions to the labour market: first, they train people, and second, they reveal talent much faster than large bureaucratic companies (in some sense, startups provide employee screening service for the market).

In Estonia, startups employ 14,396 people (one in every 38 working people in the country). This translates to 1.8% of the total workforce directly engaged in startup activities, with startup employment growing 36% annually in recent periods.

Estonia’s top 20 startups account for 59% of technology sector jobs, with Wise leading with 2,006 employees, followed by Bolt (1,329 employees). Despite concentration, the ecosystem supports diverse employment across sectors.

Besides employment, startups have a significant impact on another key economic factor: productivity. With the startup creation rate declining from 13.7% in 1978 to 8.4% in 2020 in the US, productivity growth followed the same downward trend. This correlation is not surprising, as 25% of overall productivity growth in the US manufacturing sector is attributed to net entry, which is the difference between new firms, including startups, entering the market and old firms leaving the market (although today manufacturing constitutes just 10% of the US economy, its data is very detailed, so we use this sector to illustrate the impact of startups on productivity. The same positive impact exists in other sectors but the data is less detailed).

Startups support competition

By their innovative nature startups challenge incumbent companies’ solutions and products and introduce essential competition in the market. Without it, big enterprises feel complacent and stop investing into research and new technologies. Competition with other young enterprises benefits startups too, as it induces them to think about out-of-the box solutions, which drives innovation. Young entrepreneurs, that even in the most innovation-driven environments make up only 1-2% of the workforce, by identifying market gaps and finding solutions to them can sometimes create new markets and even industries. Tesla or Airbnb that started like usual startups revolutionized entire industries, changing perspective on electric vehicles and accommodation rentals respectively.

Over the past two decades, startups have played a significant role across a variety of industries, including digital and green transformations. The fintech sector with examples of new solutions like Venmo (US) Revolut (UK) is a completely new field that undermines the traditional financial model offering faster, more user-friendly, and innovative solutions. It urged all “traditional” companies to adapt to stay competitive, and today you can hardly find any major Western bank without a web or mobile application.

While macroeconomic factors like GDP growth and inflation provide the backdrop for startup success, three core pillars are even more crucial. First, access to capital—the funding entrepreneurs need to grow; second, the legal and regulatory environment, including ease of doing business and intellectual property rights protection; and third, human capital —the talent pool and supportive education that help new ventures thrive. Next we consider these factors in the US, Estonia, and Ukraine.

Funding of startups: venture capital

Figures 1, 2 and 3 show how much capital is available in the US, how many deals are made and how startup founders manage to sell their companies.

Figure 1. Number of deals and amount of funding provided by venture capital firms, the US

Source: Startup Blink

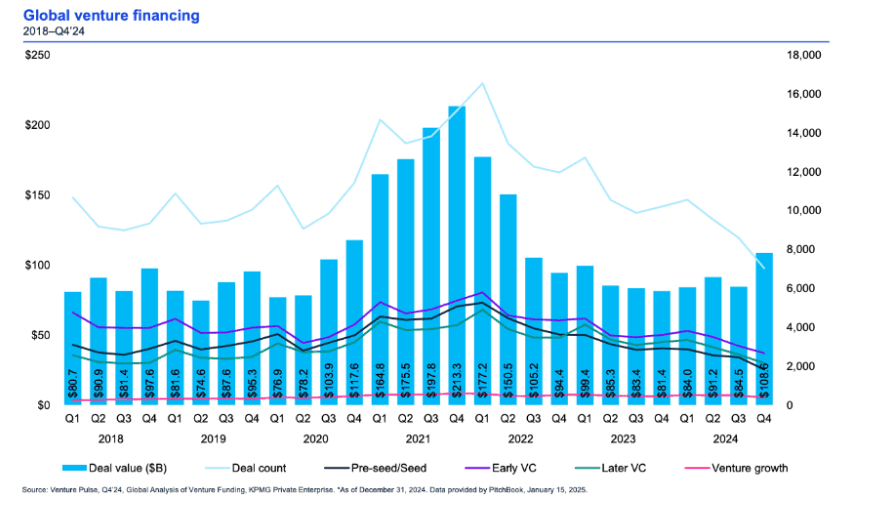

The US has the largest venture funding market, with its volume equal or higher than Ukraine’s GDP (figure 1). There was a notable upward trend in both deal activity and available funding prior to 2021, largely driven by the bull run in tech stocks and historically low interest rates. However, after 2021, several factors contributed to a decline in market activity. Market uncertainty stemming from the ongoing impacts of COVID-19, coupled with rising interest rates, led to decreased investor appetite for risk, causing both funding and the number of deals to drop significantly.

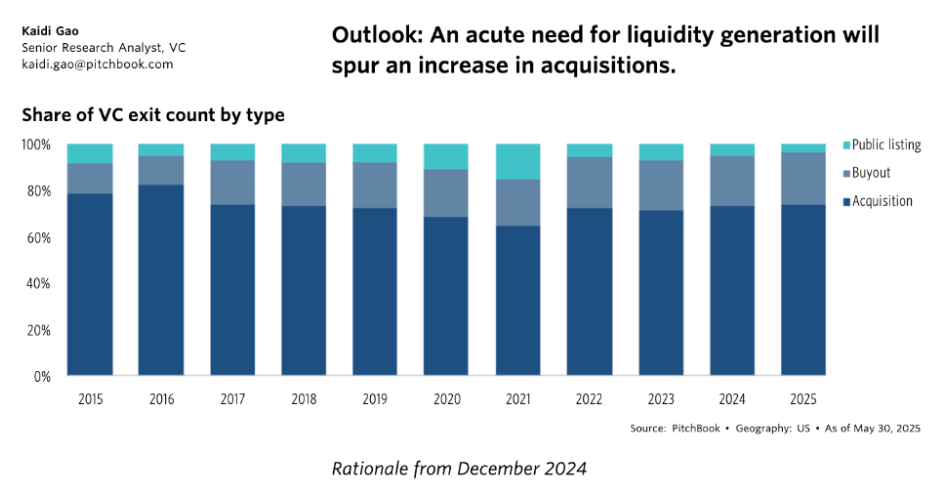

After 2021, the amount of IPO listing also declined (figure 2), as market conditions made public offerings less attractive for many companies. Overall, these shifts mark a clear turning point in the investment landscape after 2021. Now the market starts to recover, but it is still unclear when the US ecosystem will reach its prior record levels.

Figure 2. Share of VC exits by type

Source: KPMG report. Note: Exit is the way for a fund to realise gains

The global venture capital market is experiencing a decline, a pattern visible in the US and globally. At the same time, while the total amount of early-stage investment has decreased, the proportion of overall deals going to Seed and Pre-Seed round (Seed is typically the first round of investments and Pre-Seed is ideation stage funding) has increased. This shift can be positive for startups, as it reflects an ecosystem where companies can achieve meaningful results with smaller teams and less funding. However, it also means late-stage funding is harder to obtain, so startups must be efficient and demonstrate strong fundamentals to grow or attract larger investments.

Figure 3. Trends in Global Venture Funding and Investment Deal Share by Stage and Series

Source: KPMG report

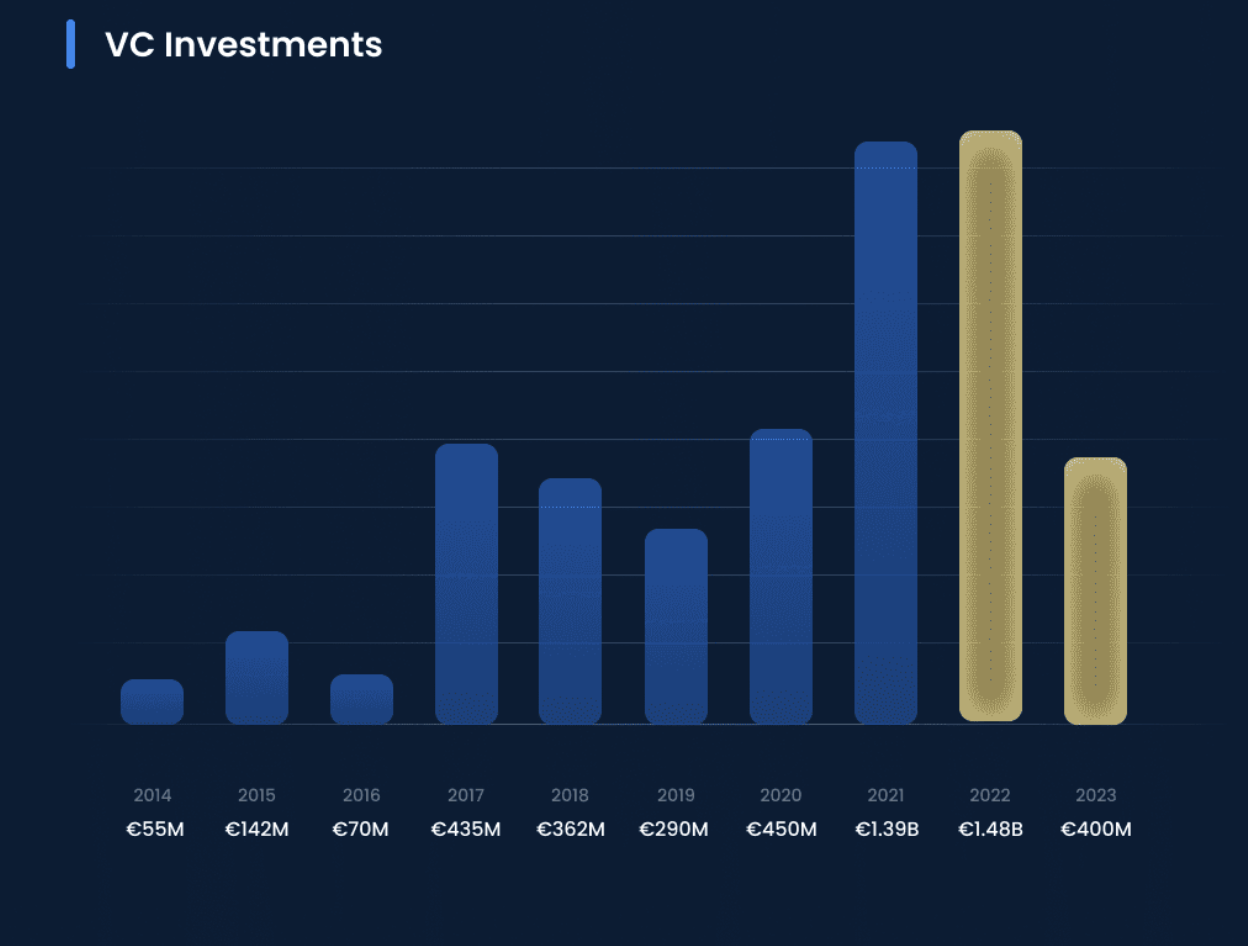

Estonia’s startup investment activity is more volatile than that in the US. This pattern reflects the country’s compact market size and sensitivity to global trends. Despite this, Estonia’s ecosystem has produced numerous unicorns and is among the most dynamic and advanced on the global scale.

One of the defining moments in the history of Estonia’s startup ecosystem that established Estonia’s global credibility was the success of Skype, an application largely developed in Estonia. Skype’s acquisition by Microsoft in 2011 delivered a significant amount of capital to the local scene. Many of Skype’s founders and early employees—collectively known as the “Skype Mafia”—channeled their expertise and financial resources into launching and backing other ventures such as Skycam, Teleport, and SpaceApe. This phenomenon demonstrates how a single major exit can catalyze broad ecosystem growth, creating a cycle where early success breeds further innovation and investment.

Building on this momentum, the Estonian public sector has played a key role in shaping the country’s startup identity through bold and highly effective marketing initiatives—the likes of which are rarely seen elsewhere in the world. Notable examples include globally copied innovations such as e-Residency, Nomad Visas, and the positioning of companies as fully digitized. E-Residency and the Nomad Visa (i.e. an opportunity to become an Estonian resident without actually moving into the country) have attracted global talent and capital to Estonia, while the country’s embrace of digital-first governance and streamlined business registration has made it exceptionally easy for founders to launch and operate tech companies. (Note that Estonia is also one of a few countries that uses distributed profit tax instead of a profit tax. This may be another factor of its attractiveness for investors. However, Diia.city offers a similar option. Besides, distributed profit tax requires a much higher level of tax compliance/enforcement than there is currently in Ukraine, so for now we do not recommend switching to this taxation model).

In 2015, TransferWise (now Wise) was founded, with the biggest ever single investment in the Estonian market. In 2017, Estonia hosted the Startup Nations Summit 2017, a flagship global entrepreneurship event, bringing together leading policymakers, entrepreneurs, and investors. This coincided with Estonia’s presidency of the EU Council and showcased the country’s digital governance and innovation culture to the world and launch of the Baltic Innovation Fund. This laid the foundation for future booms of 2021 and 2022 and led to huge funding rounds for Bolt, Zego and Wise. These initiatives greatly increased venture activity in Estonia (figure 4).

Figure 4. Venture capital investment in Estonia over time

Source: Estonia startup ecosystem report

The level of government engagement in Estonia, marked by bold experimentation and proactive marketing, contrasts sharply with the more hands-off regulatory approach commonly seen in the US. In the US, innovation is often supported through targeted financial incentives and funding programs rather than direct government-led ecosystem building.

For example, the US offers a Research and Development (R&D) Tax Credit that allows companies to reduce their tax burden based on R&D expenditures, enabling firms to reinvest those savings into further innovation. Additionally, the Qualified Small Business Stock (QSBS) exemption permits investors to exclude up to 100% of capital gains on certain startup stocks, incentivizing investment in early-stage companies.

The Economic Development Administration (EDA) provides grants that offer no-strings-attached funding to support startups and foster regional economic growth. While the US does not have a direct equivalent to Estonia’s pioneering e-Residency program, it facilitates foreign entrepreneurs’ entry and settlement through visa pathways such as the O1-A visa and the International Entrepreneur Rule. The latter allows founders of established startups—with demonstrated potential for rapid growth and job creation, including raising at least $311,071 in funding—to stay in the US while growing their business.

Together, these programs reflect a more indirect but financially driven approach to fostering innovation and entrepreneurship, relying on tax incentives, funding programs, and immigration pathways, but for more established startups to support the startup ecosystem in the US.

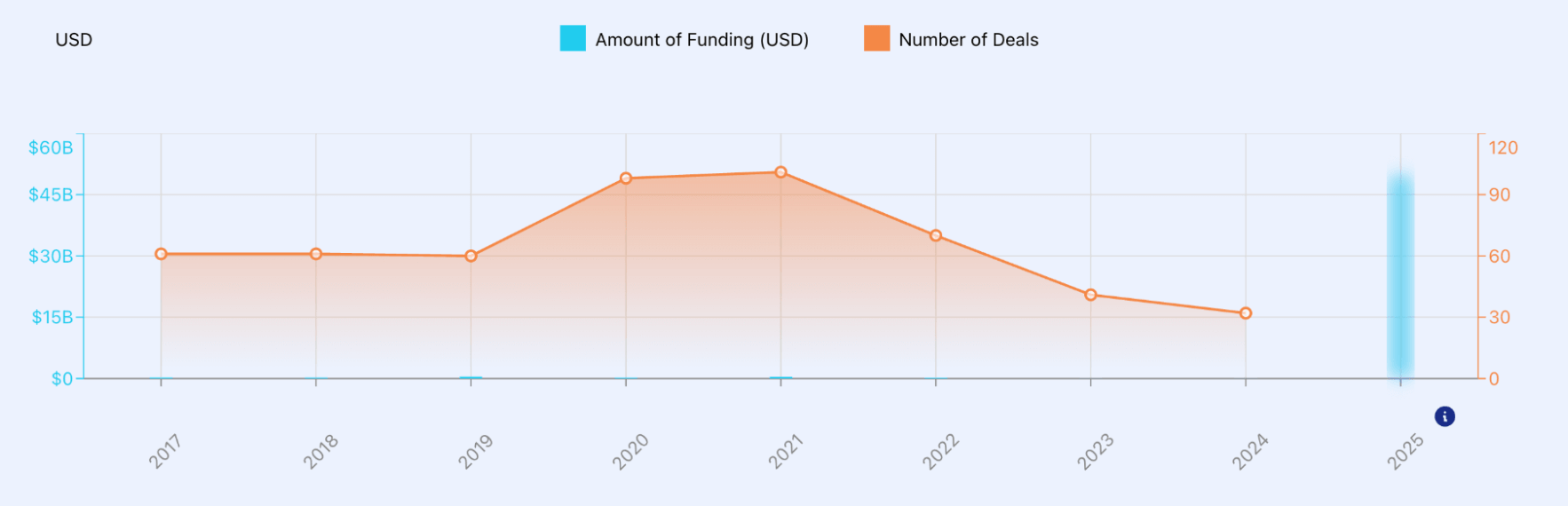

Ukraine has the most recent development in the venture capital sphere with the first notable funds being TA Ventures founded in 2010 and AVentures founded in 2012. Recent trends represented below closely follow the US pattern, however, the sum of investment dropped from the peak of $415 million in 2021 to $19.33 million in 2025 (a 95% drop) due to the war (figure 5). As noted above, the US market declined from $365 to $200 billion (-45%) in the same period due to COVID and rising interest rates, while Estonia dropped by 77% because of the same factors and war uncertainty.

Figure 5. Startup Funding Activity in Ukraine

Source: Startup Blink

Ukraine has far less resources for startups than the US or Estonia. Ukraine has just 23 accelerator programs and 76 investment funds compared to over 3000 accelerators and 3,400 funds in the US, and 39 accelerators and 117 funds in Estonia. Per capita numbers in Ukraine are also lower (table 2). However, per 100 startups, Ukraine actually has a higher ratio of accelerators and funds than the US, despite its overall smaller ecosystem.

Table 2. Comparative Startup Ecosystem Resource Indicators

| Country | Accelerators per 1M people | Funds per 1M people | Accelerators per 100 startups | Funds per 100 startups |

| US | 8,68 | 9.84 | 0.24 | 0,28 |

| Estonia | 28.66 | 85.99 | 2.68 | 8.06 |

| Ukraine | 0.6 | 2.0 | 0.88 | 2.92 |

| Country | Total Funding (USD) | Population | Per Capita Funding (USD/person) |

| Estonia | 518,490,000 | 1,360,546 | 381 |

| Ukraine | 21,690,000 | 37,860,221 | 0.572 |

| US | 200,530,000,000 | 345.426.571 | 580.52 |

Sources are added as hyperlinks (traxcn.com, nvca.org, and uatechecosystem.com)

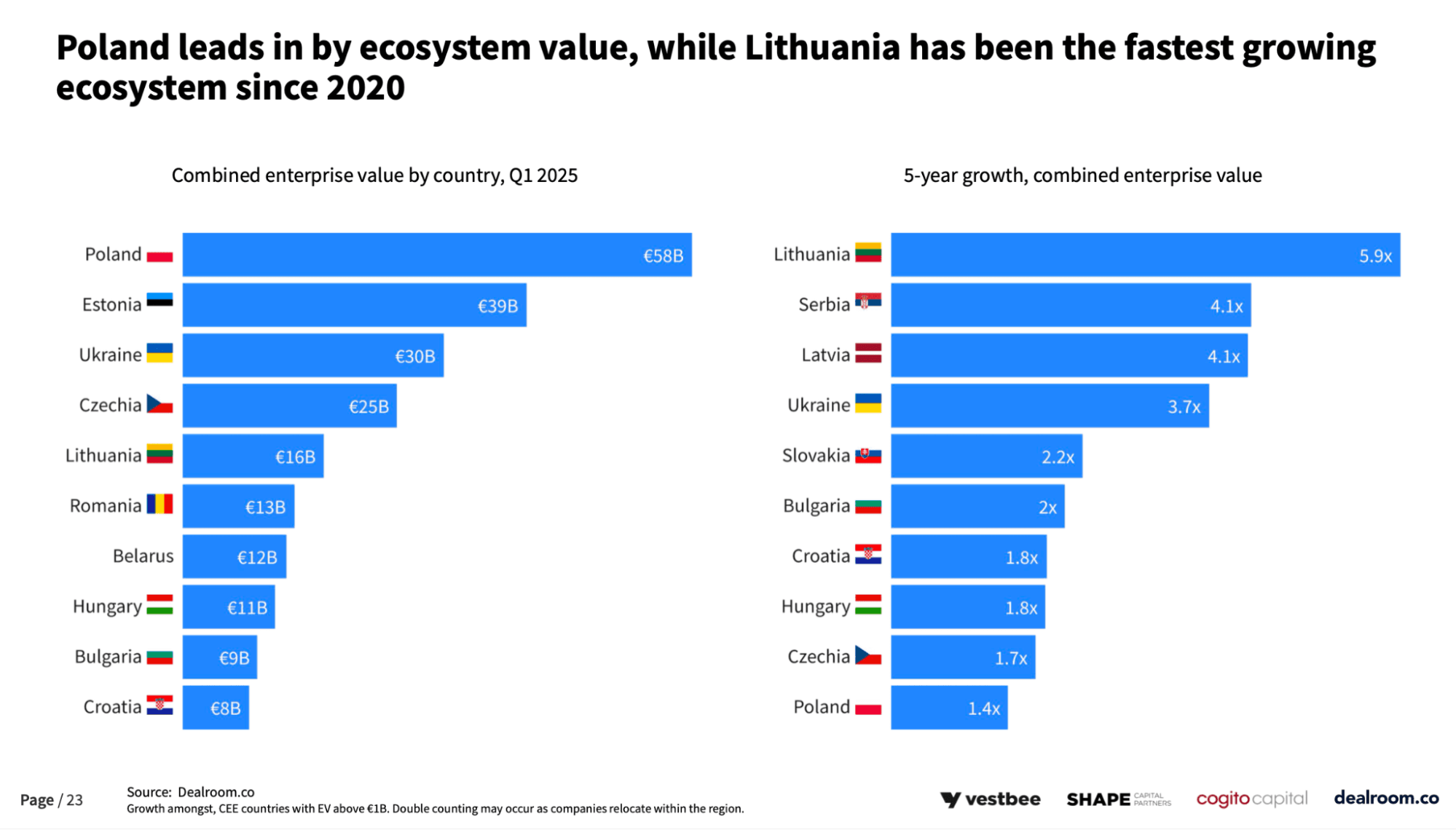

Despite the vast disparity in resources, Ukraine’s unicorn count is impressive. Estonia, with 666 times higher funding per capita, has 10 unicorns, while Ukraine has 6 (Grammarly, airSlate, People.AI, Genesis, Creatio, GitLabs). The US, with 1,014 times greater funding, has 1,048 unicorns, which is just 174.6 times more than Ukraine (figure 6). More importantly, Ukraine is ranked 3rd by the combined value of its startups, which is only 23 percent less than Estonia. Even with much lower access to capital, Ukraine has managed to perform remarkably well, which highlights its exceptional startup efficiency and potential.

Figure 6. Startup enterprise value and growth rate

Source: Therecursive.com

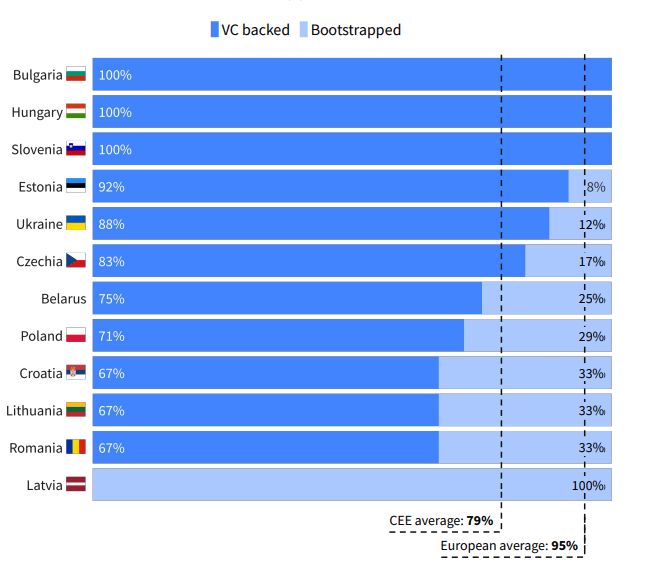

The disparity in startup creation across countries can be attributed in part to the nature and source of initial investment. Globally, there is a trend toward greater early-stage investment, yet in the US, the majority of startups—approximately 70–80%—are self-funded or supported by friends and family. This is largely due to the higher GDP per capita and greater purchasing power in the US, enabling many founders to bootstrap their ventures without needing to give up equity early on. The situation in European countries is markedly different: 92% of Estonian startups and 88% of Ukrainian startups have received venture capital backing. This dynamic suggests that in smaller markets, where founders may have less personal capital and venture-friendly regulations are in place, there is a strong opportunity for venture funds. In these markets, VC investors are especially needed, as startups tend to rely more heavily on external backing from the outset.

Figure 7. Share of VC-Backed vs. Bootstrapped Startups in Central and Eastern Europe

Source: Dealroom.co

Incorporation & company formation: Delaware vs Estonia vs Diia.City

The US, Estonia, and Ukraine each present distinct approaches to startup incorporation, reflecting different priorities. Incorporation choice is the crucial strategic decision for any startup as it determines tax exposure, investor confidence, and the market orientation.

Delaware C-corporation

The best approach for startup formation in the US is the well-known Delaware C-corp (Delaware corporation). Even though it is not the only possible incorporation option – others include Wyoming C-Corp, Delaware LLC, and Nevada C-Corp – it is the only one considered reliable and worth investing in by all VCs and institutional investors. All the investor infrastructure, such as standard term sheets, legal documents, and equity structures, is based on the Delaware law. Delaware is attractive due to favourable conditions for both young and experienced businesses such as flexible corporate laws, tax privileges, and business-friendly legal system.

Tax advantages in Delaware help companies to save lots of money. Typical state corporate tax in the US is usually between 4% and 9% (e.g., in California – 8.84%, in New York – 6.5%). In Delaware, companies registered but not doing business there are exempt from corporate income tax and pay only a franchise tax. The value of the franchise tax is based on the total number of shares the corporation is authorized to issue. Minimum tax is $175 per year, while most corporations pay $200,000 per year in state taxes to Delaware. That’s why Forbes ranked Delaware as the state with the second-lowest business costs in the US, after North Carolina.

Equally important is investor confidence in companies registered as Delaware Corps. They support standard VC instruments like preferred stock, option pools, SAFEs (investment contracts providing investors future equity in exchange for early funding), offering a straightforward transferability of shares and strong limited-liability protections.

Delaware corp incorporation process

Foreigners, except residents of Cuba, Iran, North Korea and Syria, can open an LLC in Delaware without the need to travel. However, they need a local agent that will act as their representative on the ground. An agent can be easily hired online for $200-300 per year.

To start a business in the US, every founder needs an EIN (Employer Identification Number) used for taxation, hiring employees, and other purposes. US citizens can instantly receive it via an online portal using their Social Security Number, while foreign founders must apply via fax or mail, which takes 1–4 weeks and 6–8 weeks respectively.

However, in practice, most founders use a registered agent’s online system to speed up the process. Overall, US citizens can incorporate a Delaware corporation within 1–3 business days, while foreigners usually need about 1–3 weeks.

Estonian E-residency

In recent years, a boom happened in the Estonian startup industry, and thousands of new companies are being registered in Estonia per year. The reason is a unique e-Residency program that enables entrepreneurs worldwide to register and run an Estonian OÜ (Limited Liability Company) 100% online. Some experts call it a European answer to Delaware corp. Estonia is a member of the European Union, meaning it is a part of the largest single market in the world. Setting up a business in Estonia provides access to this rapidly developing market and opens opportunities in the EU as well as high-growth regions like Eastern Europe, the Baltics, and the Nordics.

Startup incorporation process

Table 3. Comparison of special startup tax regimes in the US, Estonia and Ukraine

| ESTONIA (E-RESIDENCY) | US (DELAWARE) | UKRAINE (DIIA.CITY) | |

| State fee to register business | €265 | from $90 | ~ €17–€60 (LLC registration before switching to Diia.City status) |

| Time taken to register business | 2 hours (1–2 days if submitted on weekends or outside of business hours) | 5–15 working days | 1 working day (fully online) |

| First year costs | from €200 | from $2,500 | Minimal registration fees + Diia.City residency application |

| Corporate Income Tax Rate, per cent | 22 | 8.7 | 18 (classic) or 9 (distributed profit tax) |

| Stock transfer taxes | No | No | No |

| Digital ID card | Yes | No | Yes (via Diia app) |

| Online set-up | Yes | Yes, in part | Yes (entirely online) |

| Minimum share capital | €0.01 per shareholder | Nil | ~ €1 (1 UAH) for LLC |

| E-services | Estonia has streamlined its e-services for the remote management of businesses. E-residents are provided with a transnational digital identity, which allows 24/7 safe and secure use of Estonian public e-services. | Variety of E-Services. Not considered user-friendly, variations across states. Delaware promoting an upcoming streamlined “eCorp Business Services” (eCorp 2.0). | Diia.City provides a fully digital legal & tax framework: residency agreements online, simplified reporting, preferential taxation, and unique corporate tools (e.g., gig-contracts). |

| Average time to file taxes per year | 50 hours | 175 hours | ~50–60 hours (through Diia electronic reporting) |

Estonia is the only country in the world providing foreign nationals with a fully digital gateway to start and run a business remotely through the e-Residency program (unlike Estonia, Delaware does not have a digital access program in place). Obtaining e-Residency typically takes 3–8 weeks, and it is a digital ID that grants access to Estonia’s online business environment. Once approved, an entrepreneur can easily incorporate a company in Estonia (company registration is only possible after receiving e-Residency). Like with Delaware, a completely foreign-owned company will need a local contact person and legal address that cost from 200 euro per year for virtual office and sometimes could even include bookkeeping.

While registering a company in Delaware for a foreigner typically takes 1–3 weeks, an Estonian company after its founder received e-Residency can be incorporated fully online in just 2 hours, with the record being 15 minutes and 33 seconds. Delaware incorporation costs start at USD 200–500 (including state fees and a registered agent), Estonia charges roughly EUR 1,500 (EUR 150 for e-Residency, EUR 270 for state registration, and the rest for a contact person with deferred minimum share capital of EUR 2,500). For comparison, Germany requires a minimum share capital of EUR 25,000 with at least EUR 12,500 paid upfront. Estonia offers digital convenience and automatic EU legal integration that attracts founders worldwide, whereas Delaware retains stronger network effects among US-focused venture capitalists.

Taxation

Another advantage of incorporating a startup in Estonia is its tax system. Companies pay 0% corporate tax on profits that are kept or reinvested, and only pay tax when distributing profits as dividends. The dividend tax rate is gradually increasing – from 14% to 20% and now 22% – meaning that for every EUR 100 distributed, EUR 22 is received by the state as a tax, and EUR 78 goes to shareholders.

Ukrainian Diia.City

In 2022, Ukraine launched its response to Delaware’s corporate law and Estonia’s e-Residency. It is Diia.City – a unique legal and tax framework specifically designed to attract IT companies, tech startups, and innovative businesses. Unlike Delaware C-corp or Estonian OÜ which are special legal entities, Diia.City is a special status that an eligible Ukrainian company (usually an LLC) can shift to. Diia.city resident status provides preferential taxation, flexible employment options, and modern corporate tools aimed to compete globally for startup registrations thus boosting Ukraine’s integration into global technological markets.

One of the significant aspects compared to other types of companies in Ukraine are the preferential taxation conditions. Diia.City offers two types of corporate profit tax: either the classic 18% profit tax or a 9% distributed profit tax. Personal Income Tax on employee salaries, which is normally 18%, is reduced to 5%. One of the biggest advantages of preferential taxation for employees is the Unified Social Contribution, which for Diia.City is 22% of the minimum wage rather than of actual salary, allowing high earners to save a significant amount of money (at the same time, these privileges imply less money for the public sector, i.e. pensions, defense etc.). The nationwide military levy is 5%.

Unlike Delaware Corp and e-Residency, Diia.city provides unique legal tools such as gig-contracts that are a combination of labor and civil agreements. They offer social protection and warranties for temporary workers.

For example, a company developing a drone with computer vision detection needs short-term assistance from a machine learning specialist. They find a specialist, and instead of committing to a full labor contract, since they require help only once and for a limited time, sign a gig contract while still offering all the social benefits (paid vacation, sick leave, and pension contributions). Gig contracts clearly define the project timeline for which the worker is employed and the deliverables (for example, a working AI computer vision module). This arrangement allows the cooperation to end smoothly once the project is completed, without going through complex Ukrainian firing procedures.

Human Capital

The startup ecosystem relies fundamentally on human capital—a mix of technical expertise (tech talent) and education resources. Highly skilled talent, especially in fields like software engineering, data science, product design, and business develеopment, is essential for turning innovative ideas into scalable businesses. It is not surprising that more than 51.4% of entrepreneurs globally hold at least a bachelor’s degree, reflecting the high level of education required for startup success.

Thus, we can expect that the more citizens obtain higher education, the more startups per capita will be created. On average in OECD countries (38 advanced market economies including the US, Europe, Japan, and Australia) 40% of adults (25-64) have tertiary education while in the US this share is 36%. In Ukraine, about 50% of the population have a university degree but the quality of education at some institutions is questionable.

University Impact

The US currently has around 4,000 degree-granting postsecondary institutions (12 per million population), and according to QS World Rankings, 35 to 40 of the world’s top 100 STEM universities are in the US. MIT holds the top spot, and Stanford ranks third, making the US the most densely represented nation among elite technology schools. This allows the US to attract and train the best technical talent that contributes to entrepreneurial activity.

By contrast, Estonia has only 22 universities (16 per million population). The highest ranked is the University of Tartu (#238 in the global university rankings), followed by Tallinn University of Technology (TalTech), which is ranked #567 in engineering worldwide. The importance of education is especially evident in Estonia’s startup sector: 61.4% of startup employees hold a higher education degree compared to just 37.1% in the general population. Among them, 35% have a BA or higher degree (vs. 26% nationwide), 26.1% hold a Master’s degree (vs. 10% nationwide), and 1.6% possess a doctoral degree (vs. 1% nationwide).

Ukraine has the highest number of tech graduates in Europe, producing over 23,000 IT specialists per year. Among 189 Universities (5 per million population) offering tech programs the most prominent are Taras Shevchenko National University, which ranks between #721–1535 globally in different rankings (QS World University Rankings and CWUR), Lviv Polytechnic National University, recognized as the best technical university in Ukraine and typically ranked in the 1001–1200 range globally, and Igor Sikorsky Kyiv Polytechnic Institute, one of Ukraine’s leading technical universities, ranked 801–850 globally in the QS World University Rankings 2026. These institutions serve as the backbone of Ukraine’s STEM education ecosystem and are central to developing the next generation of innovators.

Table 4. Some indicators of engineering talent in Ukraine, US, and Estonia

| Country | Population | Universities (Absolute number) | Universities per 1M people | Tech Talent (total number of software engineers) | Tech Talent per 1M people |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US | 345,426,571 | 4,000 | 11.58 | 4,400,000 | 12,738 |

| Estonia | 1,360,546 | 22 | 16.17 | 36,000 | 26,460 |

| Ukraine | 37,860,221 | 189 | 4.99 | 285,000 | 7,528 |

Sources: compiled by authors, sources are provided as hyperlinks

Tech Talent

As knowledge in scientific and technical fields becomes more complex, teams grow larger and more specialized, driving strong demand for advanced skills. This rapid pace of innovation means that much of what students learn at a university quickly becomes outdated, making the quality and adaptability of professional talent one of the most decisive factors for startup ecosystems.

Despite the growing need for highly adaptable talent, the US has faced challenges in this field. Over the past 20 years, the share of startups founded by PhD holders has declined by 38% with a similar drop in the share of PhD holders in science and engineering working in startups. Despite these declines, the US remains a global leader in professional software talent with 4.4 million software engineers in 2024, making up 22% of the worldwide total of 20 million. In the future, the demand for computer science expertise in the US is projected to grow by 15% on average.

In contrast, Europe in 2023 had about 6 million software developers, making it one of the most competitive regions in the global tech labor market. While, as shown in table 4, the US leads in absolute numbers of universities and tech talent, Estonia beats both the US and Ukraine in per capita comparison. With 16.17 universities and 26,460 tech specialists per one million people, Estonia outperforms both the US (11.58 universities and 12,738 tech specialists per million) and Ukraine (4.99 and 7,528 respectively). This difference helps explain why in recent years Estonia is the leader in overall startup ecosystem growth, and has the highest per-capita unicorn number, despite having lower per capita startup funding than the US.

One of the main reasons for Estonia’s strong position on the European tech talent market is a positive net migration rate, maintained for seven consecutive years since 2018 that peaked in 2022, partly due to refugee inflow from Ukraine. It contributed not only to an increase in the overall population number but also in the number of IT specialists, as the share of internationals working in Estonia has nearly doubled between 2019 and 2023.

Estonia’s attractiveness as a startup hub is derived from several factors. First, it is in the leading place in global tax competitiveness ranking. Second, the country’s exceptional stock option regime—offering no taxation until sale after three years and zero employer taxes—provides startups with Europe’s most flexible equity compensation structure.

The third factor is Estonia’s cost advantage. While software developers earn about €4,420 monthly – 47% less than in the UK and 114% less than in Germany – they also benefit from much lower living costs, with rent indices of 22.43 for Estonia and 28.72 for Germany. This combination of lower wages and cheaper living creates significant net savings for startups and employees alike.

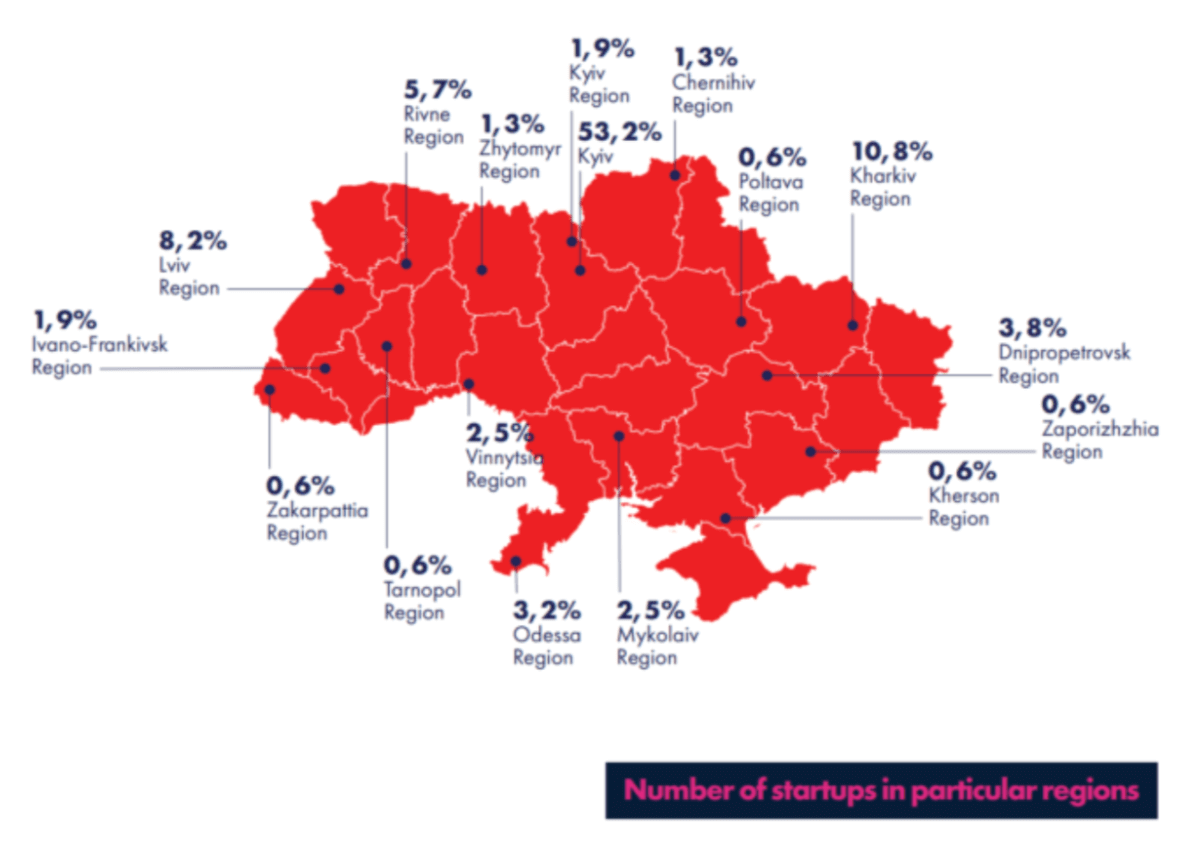

Figure 8. Regional Distribution of Startups in Ukraine

Source: Startupbridge report

Ukraine’s migration is negative due to the war. As of 2025, approximately 46% of Ukrainian tech specialists have relocated within Ukraine, moving from war-affected eastern and southern regions to safer cities mostly in western Ukraine. This internal migration has shifted the country’s IT hubs westward and fostered the emergence of new tech clusters, such as one in Transcarpathia, which now hosts over 100 relocated IT companies and around 30,000 tech specialists. Moreover, around 120,000 Ukrainian IT specialists (about 20% of Ukraine’s total 302,000 – 346,000 IT workforce) moved abroad. Human capital could be a competitive advantage for Ukraine, since Ukraine has a high level of education and low cost of living. However, the war has significantly reduced the available talent pool.

Conclusion

Startups remain among the strongest global drivers of innovation and growth. Yet, startup ecosystem performance varies sharply. The US leads in absolute scale, hosting over 1.2 million startups and allocating approximately $250B in venture funding in 2024, but its startup ecosystem growth in 2025 has slowed to 18.2%, reflecting market saturation. Estonia and Ukraine, though far smaller, outperform in efficiency and growth expanding by 34% and 26% respectively.

Global capital markets have been in decline since 2021, except Estonia, where decline started in 2022. The decline is the result of a market overheating, increased interest rate, and COVID-19 pandemic. This shift could signal a new trend — a general market shift to earlier stage investment, which is typically smaller. This could be attributed to the fact that for the first time in history, due to AI innovations and increased quality of talent, small teams could build large companies with smaller budgets.

Interestingly, smaller countries that have lower GDP per capita have the majority of their startups venture funded rather than bootstrapped. In Ukraine, 88% of startups are venture funded, and in Estonia 92%, while in the US approximately 70–80% of startups are self-funded or supported by friends and family. In per capita terms, Ukraine has the lowest venture funding per capita of 0.572 dollars, but despite low resources, Ukraine’s unicorn count is impressive.

Estonia, by contrast, shows how digital governance and bold policy, such as e-Residency and a 0% tax on retained profits, can turn a small nation into a global innovation hub. Ukraine’s path blends both models. Through Diia.City, it introduced a fully online legal environment, a 9% distributed-profit tax, and flexible gig-contracts, positioning itself as Eastern Europe’s most progressive regulatory framework.

Ukraine’s greatest advantage is its people. With Europe’s largest number of tech graduates, strong engineering culture, and high general education levels, Ukraine’s talent continues to drive innovation even under wartime pressure. More than 300,000 IT specialists now anchor an ecosystem that competes internationally despite minimal resources.

Ukraine has already proven that innovation can emerge from constraint. If it continues expanding access to venture capital, deepens global investor links, and sustains its digital reforms, it could evolve from a resilient outlier into Europe’s next major startup nation—the one built on ingenuity, efficiency, and resolve rather than scale alone.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations