Today, Ukraine faces an unprecedented demand for workers, with the most acute labor shortages concentrated in the industrial sector. But do Ukrainian adolescents aspire to build their careers in this field? Our survey indicates that, unfortunately, they do not.

According to the State Employment Center, which compared employer demand with labor supply, in 2025, labor force deficit is the most acute among electricians, plumbing technicians, industrial maintenance mechanics, lathe operators, and computer numerical control (CNC) machine operators. At the same time, the share of young people among the unemployed remains consistently high: in June 2024, more than 35% of job seekers were under the age of 25, while another 24% were aged 25 to 34. However, manufacturing-related occupations remain unpopular among young people. According to our study, only 3% of adolescents would like to work in construction, 2% in industrial sectors, and 1% in the agro-industrial sector. This already contributes to labor shortages in critical sectors of the economy and is quite likely to deepen these challenges in the context of post-war reconstruction.

At the initiative of the Olena Zelenska Foundation, the KSE Institute, in cooperation with the humanitarian organization People in Need and with the financial support of the Czech people, conducted a large-scale study titled Future Index: Career Expectations and the Development of Adolescents in Ukraine. The study examines the career aspirations of Ukrainian adolescents aged 13–16 and analyzes the key factors influencing their formation.

Survey data indicate that an overwhelming majority of children think about their future careers. Despite this, most adolescents—unlike their peers in OECD countries, as explained below—have not yet defined their professional future. Moreover, among those who have already made a choice, career decisions are not based on actual labor market demand. This situation is not unique to Ukrainian adolescents; their peers in OECD countries find themselves in a similar position, as discussed below. In recent years, particularly following the COVID-19 pandemic, the gap between young people’s perceptions of desirable occupations and the real needs of the labor market has become more pronounced. Notably, this mismatch is no longer viewed as a typical stage of growing up, but rather as a distinct problem that affects young people’s educational and career choices. Children whose career ambitions are misaligned with labor market needs are therefore likely to experience lower levels of success within it.

Only a small share of children (15%) choose the vocational and technical education track, even though it is among the spheres with the highest demand for workers. This market demand is reflected, among other things, in higher wages. Data from our survey show that this is not well understood by either children or parents. In this article, we examine in detail the state of career guidance for adolescents and the mismatch between their expectations regarding future work and what the labor market can offer.

Methodology

The survey of adolescents and their parents or guardians was conducted in March 2025 using a mixed CATI–CAWI methodology. First, mobile phone numbers were randomly selected for telephone interviews with adults (18+) who had children aged 13–16 enrolled in secondary education institutions in Ukraine. After eligibility was confirmed and parental or guardian consent was obtained, adolescents were sent a link to complete an online questionnaire.

The study sample comprised 5,089 students from across Ukraine (excluding temporarily occupied territories) and 5,089 of their parents or guardians. The parent/guardian questionnaire was used to collect information on the family’s socio-economic status.

To identify teenagers’ career aspirations, respondents were asked open-ended questions, with responses coded using the GPT-4.1 Mini artificial intelligence model and subsequently reviewed by the research team. For adolescents, the question followed the standard format used by the OECD in PISA studies: “Describe the job you expect to have in your thirties.”

Results

Despite the high level of uncertainty characterizing contemporary life in Ukraine, Ukrainian adolescents view their future with optimism and reflect on who they want to become. Eighty-two percent of Ukrainian children see their own future as promising, while only 60% express the same optimism about the country’s future.

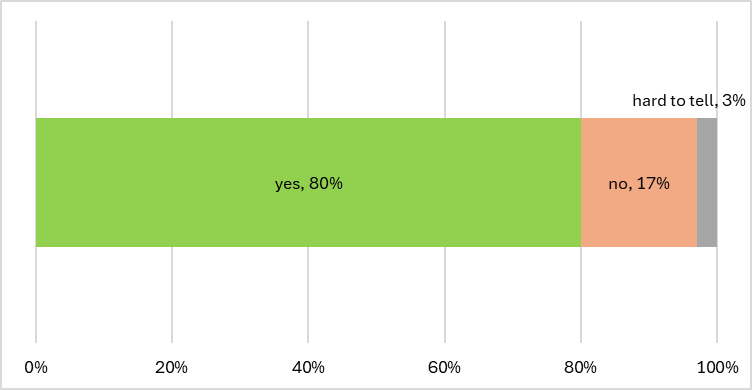

Eighty percent of adolescents think about a potential career path (Figure 1), with this share reaching 85% among girls and 74% among boys. This indicates a high level of interest among children in shaping their adult lives.

Figure 1. Have you thought about what profession you would like to pursue in the future? (N = 5,089)

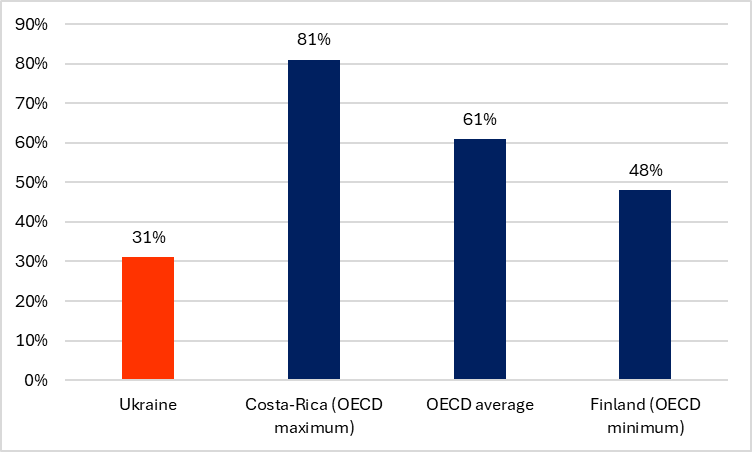

At the same time, only 31% of children have clearly determined their future specialization. Compared with European countries, this figure is extremely low. On average, 61% of 15-year-olds in OECD countries have decided on their future profession; the lowest share is observed in Finland – 48%, which is still higher than in Ukraine (Figure 2).

Moreover, younger children demonstrate greater certainty about their future profession than older ones. Among 13-year-olds, 43% have decided on a future career, whereas among 16-year-olds this share is 35% (possibly because 16-year-olds think of a broader range of occupations and approach the choice more seriously). It is evident that a substantial number of children decide on a specific future occupation only after entering higher education institutions, but this situation is suboptimal. Therefore, approaches to career guidance support for children need to be reconsidered.

Figure 2. Share of respondents who provided a substantive answer to the question “Describe the job you expect to have in your thirties” (N = 4,049)

Which professions do Ukrainian children who have already made a career choice select most often? In this article, we focus on the sectoral dimension of respondents’ answers. Open-ended responses were coded in accordance with the classification used by the Unified Vacancy Portal (UVP) of the State Employment Service.

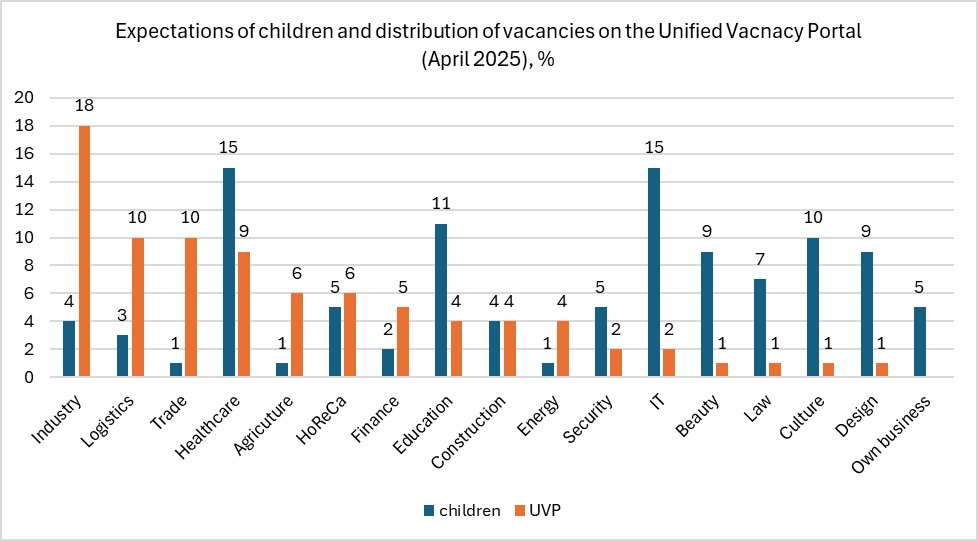

Among the most common responses were programmer (named by 85 respondents), designer (75), entrepreneur (53), doctor (51), psychologist (51), dentist (42), and lawyer (36). The five most popular sectors are healthcare (14%), IT (14%), education (7%), culture (7%), and design (7%). There are pronounced gender differences in career choice: most girls see themselves working in media, services, law, and design, while boys more often envision careers in the automotive sector, logistics and transport, agribusiness, and IT (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Responses to the question “Describe the job you expect to have in your 30s,” % of respondents who have defined their career expectations (N = 4,049), UVP classification

Note: respondents could provide multiple answers

In open-ended responses, children were able to describe which factors they consider important when choosing a future profession. These include high financial rewards (“…profitable and interesting to me”); stability (“a job that provides confidence in the future”); interest and enjoyment (“a job I love and would want to go to”); opportunities for professional development (“with opportunities for learning and career growth”); work–life balance (“a balance between personal and professional life, the ability to work remotely,” “not working overtime”); and contributing to Ukraine (“a job that benefits Ukraine”). The responses reflect a combination of material and non-material motivations: children seek not only financial stability, but also meaningful work, opportunities for development, flexible working conditions, and a sense of the significance of their activities.

Figure 4. Responses to the question “Describe the job you expect to have in your 30s,” % of those who have decided (N = 4,049)

Unfortunately, the pattern of actual demand for specialists differs fundamentally from children’s perceptions. The sectors experiencing the most acute labor shortages are industry, logistics, trade, healthcare, and the agro-industrial complex. Children, however, tend to lean toward self-realization in fields such as IT, law, or culture, where there is no urgent demand for new workers. Industry, which chronically suffers from labor shortages, remains highly unpopular among teens. This highlights a mismatch between career expectations and the actual opportunities the labor market is able to offer children (Figure 4).

Figure 5. Responses to the question “Describe the job you expect to have in your thirties,” % of those who have decided (N = 4,049), and the distribution of vacancies by the Unified Vacancy Portal (April 2025), %

How can this gap be explained? One of the key problems is the lack of a systemic approach to career guidance within the education system. At present, career guidance is conducted primarily in the final years of schooling, while younger children are generally not offered such support. Instead, the system should span all levels of education, accompanying children from an early age, identifying their creative and educational interests and skills, and aligning the needs of the modern labor market with the comprehensive preparation of future generations.

This lack of a systemic approach stems from the absence of a nationwide policy framework and from insufficient alignment among regulatory documents that would clearly govern the implementation of career guidance activities in educational institutions. As a result, career guidance is conducted by each school at its own discretion, typically on an irregular basis and not on an equal footing with other subjects. Career guidance activities usually do not require active student engagement and are limited to mere attendance. An excessive focus on tests, presentations, and excursions has little effect on the development of children’s critical thinking or practical skills.

Educational institutions also face a shortage of specialists capable of delivering career guidance activities (as noted by representatives of educational institutions during the qualitative phase of the study). These include psychologists, social educators, and career counselors. At the national level, a fully functioning system of career counselors is expected to be in place only by 2027 (currently, career counselors operate on a pilot basis in some communities under the DECIDE project, which plans to reach 600 communities in 2026). Career counselors help students identify potential future professions, taking into account their abilities and the current labor market needs. They combine the roles of counselor, psychologist, and educator.

These shortcomings effectively shift career guidance into the home environment. We asked adolescents which career guidance activities they most frequently participate in. As expected, the most common activities are those that do not require direct interaction with specialized professionals or institutions. The vast majority of adolescents discuss their future with their parents (74%) and independently search online for information about professions (56%), educational institutions (44%), or other opportunities (23%). The least common activities are those that involve direct contact with professional environments or participation in organized events. These include internships (3%), job fairs (4%), consultations with career counselors (7%), visits to educational institutions (10%), and workplace visits (11%) (Figure 5). This gap reflects both limited access to these formats and their insufficient integration into the educational environment. Notably, boys are 14% less likely than girls to engage in career guidance activities.

Figure 6. Share of “yes” responses to the question “Have you done any of the following to learn more about future education or types of work?” (N = 4,049)

Parents become the primary career advisors for children. Their role in shaping children’s career trajectories is not counterbalanced by input from other professionals. Moreover, this takes place in a context of limited career guidance information and a lack of tools for broader parental engagement. Predictably, this situation creates challenges, as parents guide their children’s career choices without in-depth knowledge of labor market needs, the current relevance or obsolescence of certain specializations, or the skills required for future occupations. In 2020, 94% of parents reported the need for more information on career guidance.

Our study found that 78% of children whose parents have higher education discuss their future with them, compared with only 67% among children whose parents have secondary or vocational education. In addition, the more affluent parents are, the more frequently they engage in conversations about their children’s future. These conversations have a substantial impact on adolescents’ self-reflection: those who discuss their future with their parents are significantly more likely to think about their future profession—83% compared with 60%. Thus, parents play a decisive role in the process of adolescents’ career self-determination.

OECD research confirms that all types of career guidance activities are positively associated with career certainty. Among the most influential factors identified in this research are reviewing online information about occupations and vocational education and training programs. Searching for information about funding opportunities and speaking with a counselor are also important.

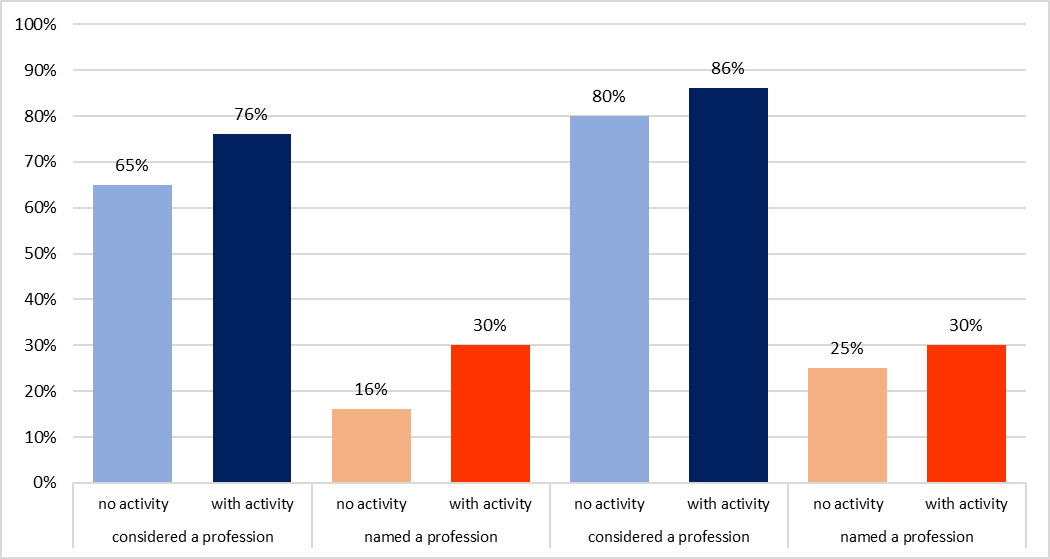

We conducted a regression analysis of the survey data and found that the more children engage in career guidance activities, the greater their career certainty becomes (Figure 6). However, children do not perceive the career guidance activities in which they participate as useful. This is likely because the formats of these activities are limited.

Figure 7. Share of responses to the questions “Have you thought about what profession you would like to pursue in the future?” and “Describe the job you expect to have in your thirties,” by gender and participation in extracurricular activities (question: “Do you attend any of the following activities?”, N = 5,089)

Figure 8. Factors associated with career certainty (logistic regression; dependent variable: stated expected profession, N = 4,049)

Note: Parental pressure on academic performance was measured using a question asking whether parents push their children to obtain good grades. The table of regression coefficients is provided in the Appendix.

Conclusions

Current needs and demands of a future reconstruction should serve as guiding principles for public policy. According to estimates by the Ministry of Economy for 2023, the labor market will require at least 4.5 million workers for reconstruction. The bulk of this demand will be for technical and manual occupations—precisely those that Ukrainian children rarely choose. Despite the evident shortage of technical and blue-collar workers, simply informing children about labor market needs does not guarantee a change in their career choices. For many adolescents, personal aspirations and visions of how they wish to shape their future outweigh economic considerations. This is why it is essential to examine the motivations of those who do choose manual occupations: which factors influenced their decisions and which conditions made these choices acceptable. Such evidence can provide a foundation for developing effective public policy in the areas of career guidance and human capital development.

To bridge the gap between teenagers’ expectations and the real labor market needs, public policy should ensure the development of an integrated system of career guidance. In the medium term, this entails introducing a cross-cutting career guidance program for grades 1–11(12), strengthening human resource capacity through the introduction of career counselors in schools and communities, creating a modern digital and methodological infrastructure, and systematically working with parents. It is also important to scale up the results of the already tested pilot model, assess its effectiveness, and adapt it to regional needs.

In the long term, key priorities include strengthening the “career management” component within the State Education Standards, introducing electronic student portfolios, and developing sustainable partnerships among schools, businesses, vocational and higher education institutions, and civil society organizations. These steps should ensure continuity in career guidance efforts and a genuine alignment between school education and the contemporary labor market.

Disclaimer: The interpretations and views expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the partners or donors.

Appendix. Regression coefficient table

Career certainty and career guidance

Dependent variable: Stated expected profession

| Variable | Coefficient | Standard error | p-value | Odds ratio |

| (Intercept) | 0.012 | 0.412 | 0.028 | 0.978 |

| Career guidance activity (any) | 0.562*** | 0.087 | 6.454 | < 0.001 |

| Age | -0.088** | 0.028 | -3.107 | 0.002 |

| Gender: Female | 0.028 | 0.061 | 0.452 | 0.652 |

| Experience of parental pressure on academic performance | -0.012*** | 0.003 | -3.942 | < 0.001 |

Note: *** significance at 0.001, ** at 0.01, * at 0.05

Photo: depositphotos.com

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations