The expectation was that Donetsk, Luhansk and Crimea are more pro-Soviet than other regions, and indeed the conflict regions are more pro-Soviet than Kyiv. However, in total eleven oblasts had percentages close to those in the conflict regions, yet they do not seem vulnerable to Russian aggression. Therefore, oblasts that have more pro-Soviet people are not necessarily more vulnerable to Russian aggression.

After the Russo-Georgian war in 2008, Daniel Treisman said Ukraine would be next in line, with Crimea as a likely flashpoint [1]. In his view, Georgia was a case of Russian imperialism and it is a matter of time when such a thing would happen once again. Britain’s foreign secretary, David Miliband invoked the Soviet crushing of the 1968 Prague Spring and said the war showed that Russia remained “unreconciled to the new map of Europe”. The U.S. presidential candidate John McCain accused the Russians of invading “a small, democratic neighbour to gain more control over the world’s oil supply, intimidate other neighbours, and further their ambitions of reassembling the Russian empire”. However, perhaps, the ambition is to reassemble the Soviet Union rather than the Russian empire and, if so, some Ukrainian citizens may have welcomed the Russian “liberators” hoping that it will restore the USSR.

In any case, why the front line stopped where it stopped is a central question. Yuri Zhukov argues that the underlying force for vulnerability of the eastern regions is their economic position compared to the rest of the country: the “European direction” of the new government could put many industrial workers in the region at risk.

Alternatively, some argue that the divide is determined by drastic differences in views between Crimea/Donbass (pro-Russian) and the rest of Ukraine (pro-Ukrainian). The potential division could be more nuanced. Specifically, it could be pro-Soviet vs. anti-Soviet. Being Russian does not mean pro-Soviet and, likewise, Ukrainian does not mean anti-Soviet. Indeed, the older generation in most post-Soviet countries, including both Russia and Ukraine, find it hard to live in a different system and many of them wish to return to the socialist regime (USSR) without having an understanding of the current system.

In order to assess the vulnerability of the regions, I look at 4 main questions.

- Whether the vulnerability of oblasts depends on their view on the Soviet system?

- Whether the vulnerability of oblasts depends on their view on the relationship with Russia?

- Were people in conflict oblasts more likely to defend their rights by aggressive forms of behaviour?

- Was there significant discrimination of ethnical Russians and/or Russian speakers in conflict oblasts?

To answer these questions, I use the 2007 Ukrainian Longitudinal Monitoring Survey, a uniquely rich data source.

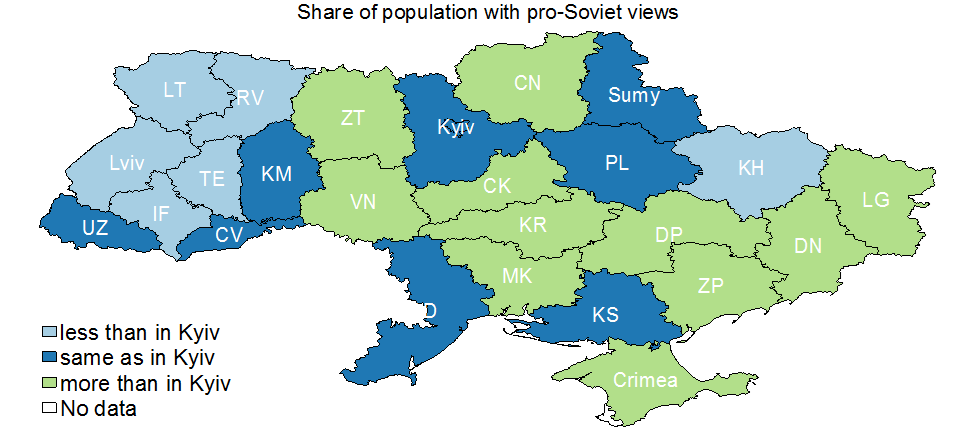

I examined answers to a set of questions in the ULMS survey in regards to the region the respondent was from. The results are presented in comparison to Kyiv on a map of Ukraine for better visualization. The label “less than in Kyiv” means a statistically significant difference from the value achieved for the Kyiv region, “same as in Kyiv” – with such statistically insignificant differences that the results are taken as the same as for the Kyiv region, and, accordingly, the same logic applies to “more than in Kyiv”. Kyiv is taken as a reference point because it is the largest city in Ukraine and is the geographical and cultural centre.

To answer the first question regarding views on the Soviet system, I combined two variables: one is linked to the Soviet political system and the other is linked to the economic system to build a variable that shows an “integral” attitude towards the Soviet system. The specific questions are what kind of political system, in your opinion, is most suitable for Ukraine and what kind of economic system is most suitable for Ukraine. I divided the answers of the ULMS survey into ones that suggested that the Soviet model is suitable, and ones that were supportive of other systems. This shows how many people see the Soviet system in general as suitable for Ukraine.

I expected more pro-Soviet people in the Donbass and Crimea, given their vulnerable position. Indeed, results showed that people in those regions are slightly more pro-Soviet than in Kyiv, where the share of people with pro-Soviet views was 32.3%. In Donetsk the share was 49.7% and in Luhansk – 54.3%. In Crimea, the share was 45.1%. Despite the results showing that the conflict regions are more pro-Soviet than Kyiv, we can see from the map that nearly half of the country share these views, however there was no military action in those regions. Therefore, the conclusion is that the conflict oblasts indeed are more pro-Soviet, yet there are other underlying reasons why these oblasts are more vulnerable.

Source: ULMS

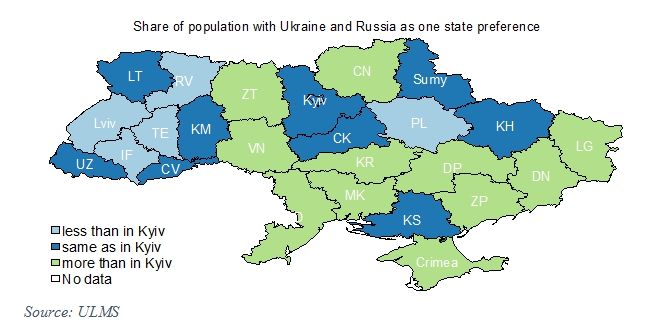

The ULMS survey provided the following options for answering the question regarding the relationship with Russia: same as with other states, closed borders, customs; more friendly with open borders; or in unity.

I expected that the regions vulnerable to Russian aggression have a higher share of people who prefer Ukraine and Russia being one state. Indeed, the map shows that people in Crimea, Donetsk and Luhansk prefer unity more than people in other regions. 11% of the people in Kyiv prefer unity with Russia, 56.9% in Crimea, 43% in Donetsk, and 37.3% in Lugansk. At the same time, many other regions have a higher share of people preferring unity with Russia, including Dnipropetrovska oblast, where the share is 39.2%. However, pro-Russian rallies in Dnipropetrovsk had not been successful.

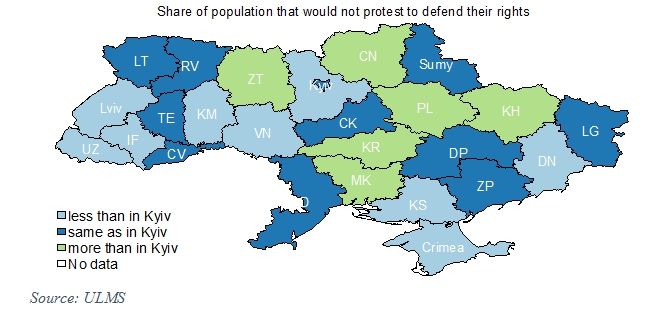

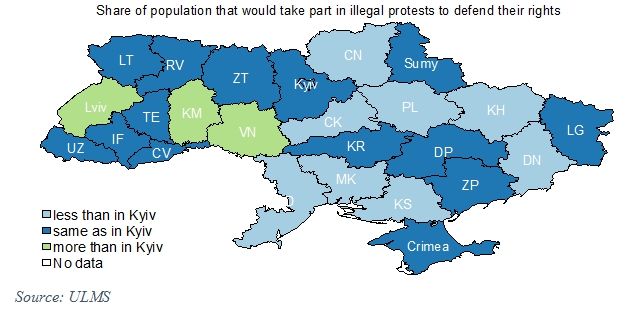

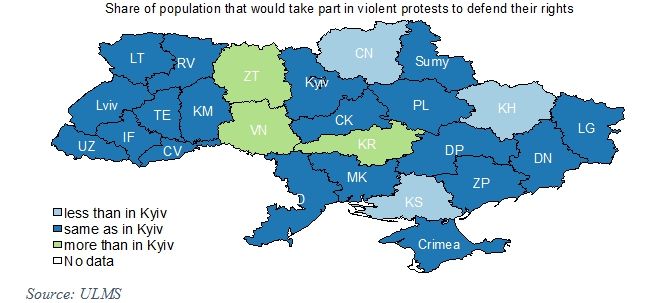

The next maps show to what extent people are ready to defend their rights. I classify people into three groups. The first group includes people who do not want to defend their rights, that is, they answered ‘no’ to all of the forms of defending their rights: legal, illegal and violent. The second group includes people who are ready to participate in illegal forms of defending their rights, such as illegal meetings, strikes, hunger strikes and picketing government buildings. The third group includes people who are ready to protect their rights in more violent ways, such as creating military units and seizing buildings. The base group in this case is people ready to defend their rights in legal ways. The question was posed in a way that people needed to choose whether or not they would take part in a certain way of defending their rights. Bearing in mind the events of the past year, I expected Crimea, Donetsk and Luhansk to be quite radical in defending their rights.

The first map shows the result for the people who responded that they would not protest in any way to defend their rights.

As we can see, the share of passive people in Luhansk is approximately the same as in Kyiv (59%). However, there are less passive people in Crimea (40.5%) and Donetsk (23.1%).

According to the self-reports in ULMS, most of the country is not very supportive of illegal means of defending their rights. In Kyiv the share of people who see illegal forms of defending their rights as plausible is 5.1%.

The next map shows that there is even more unity throughout the country regarding violent ways of defending rights. In Kyiv, the share of population is 1.7%. Only three regions have a statistically significant higher share of the population with these views. Crimea, Donetsk and Luhansk are not among these regions, suggesting that people in these regions are not likely to create militias on their own.

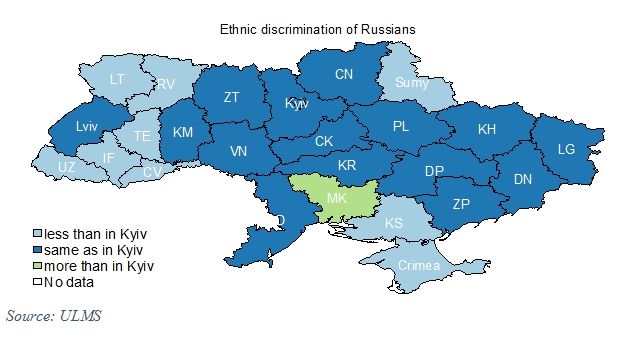

According to Putin and other Russian officials, the trigger with Russia was the alleged ethnic discrimination of Russians in Crimea, Lugansk and Donetsk (the fourth hypothesis). The expectation was that these regions would have the highest share of discriminated Russians. The ULMS survey included a question regarding whether or not the respondent felt discriminated against. It was possible to see the data by ethnic origin and by region, so I could show in which regions Russians felt discriminated against. The next map shows that Russians in the conflict regions were no more discriminated against than in the rest of the country. In fact, the average percentage of discriminated Russians across the country was 1.4%.

In summary, we can make the following conclusions.

The expectation was that Donetsk, Luhansk and Crimea are more pro-Soviet than other regions, and indeed the conflict regions are more pro-Soviet than Kyiv. However, in total eleven oblasts had percentages close to those in the conflict regions, yet they do not seem vulnerable to Russian aggression. Therefore, oblasts that have more pro-Soviet people are not necessarily more vulnerable to Russian aggression.

Donetska, Luhanska oblasts and Crimea indeed prefer unity more than Kyiv. However, other oblasts also have a significantly higher share of people preferring unity with Russia. Yet there has not been much of pro-Russian movement in those oblasts. Therefore, the vulnerability of the conflict regions does not directly depend on the preference of unity with Russia.

Data show that less than 1% of the population in the conflict oblasts is ready to protect their rights in violent forms. Thus, without external provocation and support, violence in Crimea, Donetsk and Luhansk could not have sustained.

Putin’s narrative stated that discrimination of Russians in eastern Ukraine was a key reason for intervention. However, none of the conflict oblasts happened to have a higher share of discriminated ethnical Russians. On the contrary, in Donetsk more non-Russian people feel discriminated. Therefore, there is no factual evidence of the discrimination of Russians or Russian-speakers in Crimea and the Donbass.

These findings suggest there is little difference between Ukraine’s citizens across the country, certainly much less than conveyed by Russian media.

The article got the second place in the November round of MindSketch

Notes

[1] Daniel Treisman (2011). The return: Russia’s journey from Gorbachev to Medvedev. New York: Free Press. p153-175

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations