One of the key assumptions of economic theory is the rationality of the “economic agent”. However, real people are not rational at all. The relatively young branch of the economy – Behavioral Economics (BE) – examines the distortions and biases created by our brains and gives tips on how to make people’s behavior more rational. In this article, we discuss the application of behavioral economics methods and conclusions in health care and provide the results of our survey that illustrate the theory.

Ukraine spends about 7% of GDP on healthcare (about half of which is from state and local budgets). This is less than in developed countries. However, as the population ages, these costs will increase. At the same time, it is known that prevention is much cheaper than treatment. However, prevention is not dependent on doctors but on patients – do they lead a healthy lifestyle? Do they have bad habits? Do they avoid risky behavior? Very often the answer is “no”. For example, over 7 million people in Ukraine smoke daily (although the number of smokers is decreasing). Our country is also among the leaders in alcohol consumption per capita.

From a rational point of view, it is impossible to explain why people smoke, refuse to be vaccinated or, for example, cross the street on red light. It is increases the risk of illness or injury – accordingly, it leads to lower earnings due to disability and increased costs of treatment. The behavioral economy explains this behavior and suggests ways to change it.

Why we don’t choose health. Theory

The main idea behind a behavioral economy is that, since our brain is lazy, as a rule, people do not make the best (rational) choice, but the simplest one – what first came to mind. Associations, vivid memories, even the numbers or images we saw just before the decision was made, can influence our choices – and not always for the better.

Behavioral Economics (BE), through experiments, examines logical errors and biases and provides recommendations on how they can be used to “push” a person to the right actions. Let’s look at some of these mistakes and prejudices and how they can be used for health care policy making.

Availability heuristic: we make decisions based on the knowledge available to us. The problem is that our knowledge is limited, and even specialists in a particular industry are not able to weigh all the pros and cons. In addition, the available information may consist of fake news, rumors, stories from acquaintances and more. A striking example of this bias is the panic around the coronavirus: unverified information outweighs quantitatively, it is more readily available (and emotionally colored), so conclusions are drawn from it.

To prevent panic, you need to actively disseminate materials from which a person can obtain true medical information, and not be limited to specialized resources such as the MoH website. The repetition effect also works: the more often we hear or see a statement, the more likely we are to believe it. Therefore, qualitative health information should outweigh the unverified. The data should be presented in a simple, clear form, not limited to abstracts without argumentation.

Another example – when making a decision, people rely on the information that first comes in mind. Often, it can only indirectly respond to the task at hand or not at all. For example, anti-vaccines often handle emotional information because it is easier to remember than dry statistics. So, when asked the question “Should I vaccinate a child?”, The person first mentions the death of a child who has been linked to vaccination by the media, not the statistics of disease complications.

Because the data obtained immediately before the decision is made has a particularly significant impact on the person, one of the important tasks of the doctor is to communicate with the patient, since it is after that the patient usually makes the choice that will affect his or her health. Such communication should be both honest and persuasive, clearly indicating the implications of each option. For example, you should be able to get vaccinated immediately after speaking with your doctor to minimize the risk of being exposed to other sources of information that may lead to the wrong decision. .

The next effect is confirmation bias. It is difficult to convince a person is something that he does not fit his views. If your grandmother is used to treating colds with mustard plaster, and you tell her that the most you can get from them is burns, she is unlikely to listen to you because new information contradicts the fact that she already “knows”.

Why is this happening? To accept the view of the opponent means to “lose”, to plead wrong, which causes negative emotions. And person feel negative emotions brighter and stronger than the positive ones.

Moreover, there is a known effect when, after discussion and argument, the opponent is even more convinced of his or selfrightfulness. Therefore, information activities alone may not be sufficient, especially in areas that affect the safety of a wide range of people, including health. In high-risk cases, such as epidemics, administrative measures will be more effective (such as a ban on going to schools without vaccinations) rather than information campaigns or conversations of patients with physicians.

Discounting the future: Today’s events are perceived more emotionally, seem more important, and even more real than future. For example, we would rather choose to eat chocolate bar today than get two chocolate bars in a week. Conversely, the future harm of excess sugar is not taken seriously, because it is difficult for us to imagine the link between candy now and obesity in 10 years. Therefore, people tend to give up painful or costly treatment or rehabilitation: they cannot assess the real impact of today’s decisions on their health in the future.

The risk perception theory, which is relevant to the evaluation of the future, proves that it is change in the situation which is more important for the subjective perception, not the present or future state of the person. This effect is well known to everyone: when we have a toothache in the evening, we promise ourselves to go to the doctor in the morning. We wake up without pain (the situation has changed) and we gladly forget the need to undergo an examination (although if a tooth hurts, it should still be done).

If the patient evaluates his situation as relatively positive (the disease does not bring suffering) or is subject to negative changes (expensive treatment, restrictions during rehabilitation, etc.), he will avoid the changes. The patient is most supportive of change when in crisis – for example, suffering from symptoms. This is the best time to talk to him about taking the necessary steps.

The effect of discounting the future influences the passage of preventive measures (as long as the person subjectively feels normal, he/she postpones the physical examination). Therefore, incentives are needed to get through with examinations, such as discounts on medications provided that regular examinations have been made. In general, refocusing on primary care and preventing deseases instead of treating them can have a huge impact on the effectiveness of the entire healthcare system. Early detection of diseases should result in both a reduction in morbidity and a cost savings in the secondary link.

Theory is good, but what about practice?

Researchers in the field of behavioral economics conduct many experiments to find out what factors may influence human behavior (see, for example, Rice, 2013). These factors range from cash incentives (such as contracts, lotteries) to the merchandize of goods, style and colors of packaging or advertisements, etc.

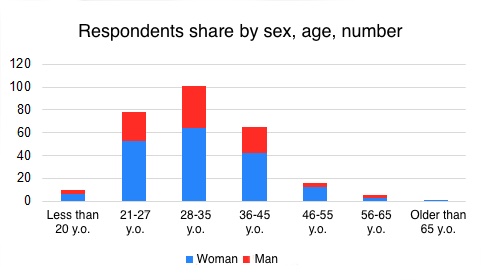

Let’s have look at some examples of the practical application of BE principles that can be implemented in the Ukrainian health care system. To illustrate these points, we conducted a non-representative survey with the FB and received 277 responses. Our respondents are mainly middle-aged people (Fig. 1), 93% of them live in big cities, 91% have higher or incomplete higher education.

Source: own poll

We asked our respondents what might encourage them to quit smoking, lose weight, become an organ donor, and how they chose a family doctor.

Greed will help you quit smoking

According to the Ministry of Health, a quarter of adults in Ukraine smoke today (about 40% of men and 9% of women). Although the number of addicts is declining, absolute figures remain high. In the “arsenal” of the state there are such means of reducing the frequency of smoking as raising excise taxes, ban advertising and smoking in public places. Let’s consider what the behavioral economy still has to offer.

The availability of information on the absolute harm of smoking and the high number of smokers is paradoxical. BE associates this paradox with the effect of discounting the future and reducing future losses, as well as with the availability heuristic : “my grandfather smoked all his life and lived till 90”. In this case, the statistics are ignored and great importance is given to the single case, which is transferred to a wider context with incorrect conclusions (if the grandfather smoked and lived till 90, the harm from smoking is exaggerated).

Most people are aware of the dangers of smoking (thus, 92.7% of Ukrainian adults think that smoking can lead to serious diseases). However, it is usually difficult to quit smoking, so in order to overcome cognitive dissonance, one justifies smoking, for example, by exaggerating the pleasure from the process.

Scott Halpern and colleagues (2015) conducted a series of experiments using financial incentives to support healthy behaviors (regular training) and quitting smoking . They have shown that the tendency to avoid losses can be used for health purposes.

The participants of the experiment were divided into three groups: the first were provided information on the harm of smoking, the second were promised to pay a premium if they last six months without cigarettes (those who can quit them for 6 months, usually no longer return to smoking), and the third group made a “deposit” with their own money which would be paid back with a bonus if the person managed to give up tobacco for the same six months and would not be returned if the attepmpt did not work. At the end of the term, the participants of the experiment underwent a biochemical smoking test to exclude the possibility of deception of the experimenters.

Those who were offered the prize more often agreed to take part in the experiment (after all, they had actually lost nothing even if they had not lasted six months). At the same time, the group that had to deposit their own funds showed the best results: twice better than the second group and 5 times better than the first. There tendency to avoid losses has worked out.

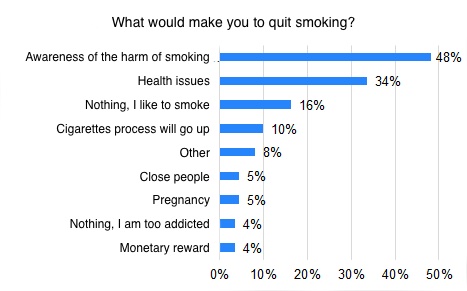

Of those who answered our survey, 40% smoke (110 people). Almost half of them believe that awareness of the harm of smoking would help them, 30% – health problems, and only 10% – cigarette prices growth (Fig. 2). 20% said that nothing would force them to quit. One person quit smoking due to the ban of smoking in public area. The survey results demonstrate both the irrationality of the respondents and the likely diminution of the influence of the price of cigarettes on their smoking cessation. According to the Ukrainian Tobacco Control Centre, the excise tax rate increased by an average of 20 times between 2008-2017, with the number of smokers falling from 10 million to 6.5 million people.

Source: own poll. Note: Respondents could choose up to 3 answers. The picture shows only those who did not choose the answer “do not smoke”.

Fight against the extra kilos: remove temptations and set achievable goals

Unlike the positive dynamics with smoking, the number of overweight and obese people in Ukraine is increasing. As of 2016, nearly a quarter of Ukraine’s population has suffered from obesity. Like other diseases that can occur due to the deleterious behavior of patients, obesity is treated by correcting such behavior.

Some eating disorders have to do with making the wrong decisions about the future, favoring ongoing gratification, and ignoring the long-term consequences of such behavior. Sweet and fatty foods are satisfying to us because in the earlier stages of human development, their consumption was profitable, because it provided the most energy. Today in most countries the problem of hunger is not acute, and this evolutionarily entrenched mechanism of rewards leads to overweight, diabetes and other diseases.

Since giving up excessively harmful food is about self-control, the BE recommends deliberately limit situations in which willpower can not cope with temptation. Even as simple as removing the calorie meal from your eyes can be effective. The same goes for making a shopping list: it’s much easier not to include your favorite cookie than to deal with it when it’s already purchased.

Short-term benefits are more appreciated by people, so short-term goals should be set when fighting overweight (reducing weight by 1 kg per week seems more achievable and realistic than by 24 kg in six months). Each such small achievement motivates you to move on and gives you self-confidence.

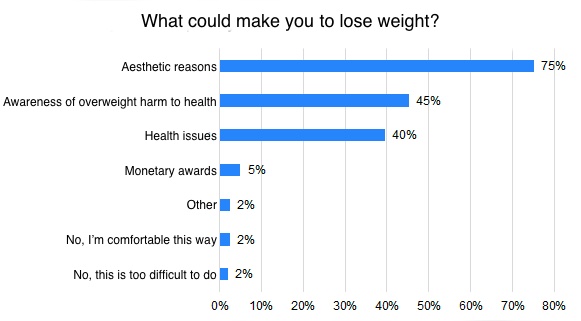

Among those respondents who are overweight (206 or 74% of those polled), 75% would be able to loose it for aesthetic reasons (this also suggests that propaganda in the media, movies, and other slim people brings ”fruits of labor”). Health problems and awareness of overweight harm totaled 84% of responses. Only 5% of respondents would be seduced by monetary rewards (Fig. 3). Again, we see the discrepancy between the answers and the results of the experiments. Kevin Volpp has shown that monetary incentives can also be effective in losing weight. In addition, we are influenced by the environment: humans, as social beings, imitate those around them. So our advice is to talk to those who will call you for a shared run, not a fast food lunch.

Source: own poll. Note: Respondents could choose up to 3 answers. The picture shows only those who did not choose the answer “I am not overweight”.

Altruism after death: how to increase number of donor?

Every year, about 5,000 Ukrainians need transplants, and most of them do not receive it. This situation is related to the lack of a donor culture, as well as to legal and procedural issues (see the link).

Any additional action that must be made is an obstacle to achieve the desired result. This applies to a doctor’s appointment, consultation, prescription and other procedures that require a certain amount of action.

There are also barriers to organ transplantations that reduce the number of potential donors. One is the legislative requirement that a potential donor give written consent or disapproval of the use of his organs after death. Under current law, in the absence of such a document, the decision rests with close relatives, which prolongs the procedure and excludes many people from the potential donors.

How can this be changed? The statutory “default consent” – that is, the need to write organ transplant rejection after the death of a donor – increases the number of potential donors at times. The level of donation in countries where a written waiver is required is as high as 90%, and where it is required to write a consent , it is 4-27%. One of the reasons for this difference is the aforementioned effect of avoidance of loss: thoughts of one’s own death are in themselves a “loss” because they are associated with unpleasant emotions. In addition, refusing to write a document saves time and effort. And since most people are lazy, they choose the easiest option – not to write a statement. And thus save others.

It is also effective to use a message in the transplant awareness campaign that each of us may need organ transplants. A question like, “would you use a donor organ if you needed it?” increases the desire of potential recipients to become donors themselves. The principle of reciprocity or quid pro quo (“you to me, I to you”), according to which people registered as potential donors can receive higher places in the queue of recipients, should also be noted.

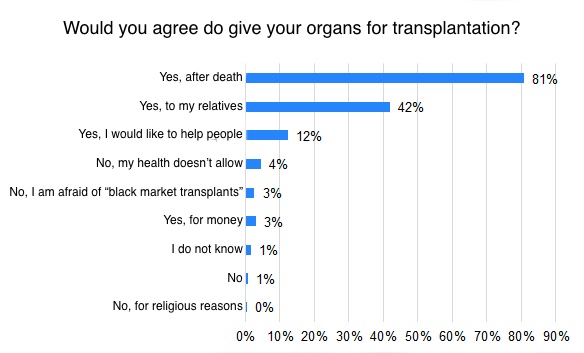

Only 8% of our respondents would not agree to become organ donors. The vast majority would agree to do so after death, just under half – for relatives only. And only for only 3% of respondents the money would be enough incentive. As you can see, the vast majority of respondents would agree to provide their organs for transplant after death. Even if to exclude those who would only agree to transplant to their relatives, this number confirms the need for a permit to use organs by default.

Source: own poll. Note. Respondents could choose several answers. Cases where the respondent chose “yes” and “no” at the same time were classified as “no”.

As we can see, behavioral economics offers an explanation for our irrational behavior, and most importantly, effective ways to partially curb this irrationality. In healthcare, where so much depends on the patient’s choice, the BE “toolkit” can change behaviors and extend years of healthy living.

Choose your family doctor. Anyone goes?

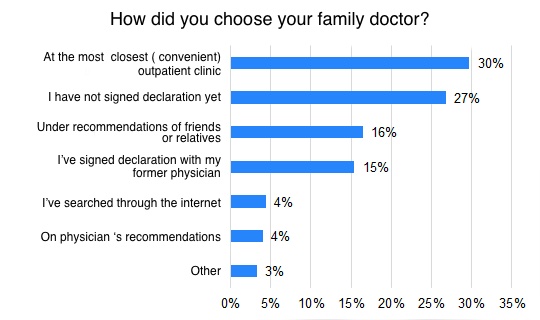

Finally, we asked our respondents how they had chosen a family doctor. After all, healthcare reform gave every Ukrainian the freedom to sign a declaration with the ones he liked best. It turned out that the majority went “the way of least resistance” and signed a declaration at the nearest outpatient clinic (30%) or with their former doctor (15%) – fig. 5. Among the other answers were “the first free doctor on shift” and “the oldest doctor among those who remained free”. 16% used the advice of friends or relatives, 4% the advice of another doctor and the Internet. Another 27% have not yet signed the declaration. 2% are treated in private clinics or have insurance.

Given these results, recommendations on how (by what criteria) to choose a family doctor would be helpful to many people.

Source: own poll. Note: The respondent could choose only one answer.

With this article, we would like to encourage you to engage in a discussion about behavioral economics and the possible implementation of its recommendations in different areas of public life: from paying taxes to improving your health.

Attention

Автор не является сотрудником, не консультирует, не владеет акциями и не получает финансирования ни от одной компании или организации, которая имела бы пользу от этой статьи, а также никак с ними не связан.