One of the old beaten truths on the ongoing Ukrainian crisis is that it is, among other things, a clash of cultures, languages, and ethnicities. The proponents of this view say that Ukraine is deeply and visibly divided into the predominantly Ukrainian speaking West that tends to identify itself with Europe and the Russian speaking East that culturally and politically leans to Russia. The recent protests and events that followed are then portrayed as just another chapter in the long lasting dispute between the two closely related but distinct ethnical groups on where their country should go.

Well respected media and honorable commentators illustrate this view with the colorful maps of Ukraine that purportedly establish correlation between the native language of a particular region and its electoral preferences. The whole crisis then boils down to a handful of simple dichotomies: East versus West, Russian speakers versus Ukrainian speakers, Greek Orthodox versus Greek Catholics and so on. An unbiased observer cannot resist a tempting question: should not those two different Ukraines just part their ways once and for all?

Political and Cultural Divide, Reproduced from www.nytimes.com

At the same time, if you ask this question to a typical Ukrainian citizen the overwhelmingly likely answer in any of the country’s regions would be “no” – at least, this is what the most recent polls suggest. To be precise, your chances of getting such an answer would be roughly 4 out of 5, and if you decide to drop from the sample Crimea dwellers or people aged over 50 – well above that. The overwhelming majority of Ukrainians want Ukraine to be united.

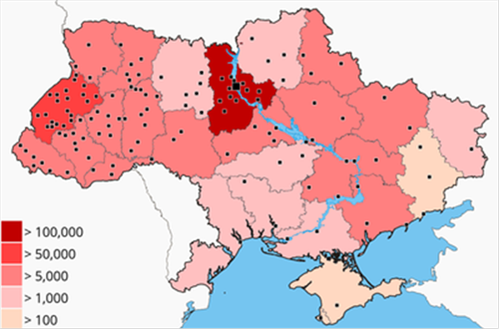

Source: poll by the Razumkov Centre (Dec 2013)

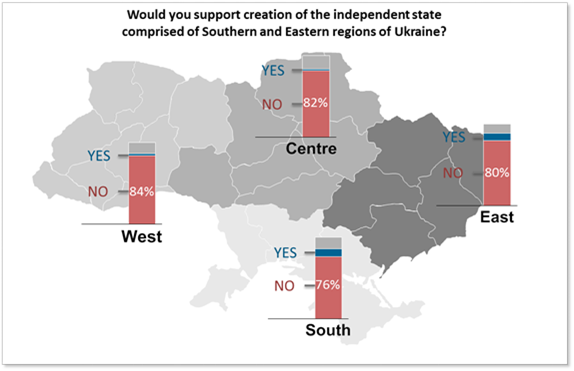

So is Ukraine divided? Well, it most definitely is, but the demarcation line is not between East and West or between Ukrainians and Russians, as some observers tend to believe. The true division line is running deep through the heart of the Southern and Eastern regions—the first map shows it clearly. While Western and Central regions come across as a rather uniformly painted land mass, the East and South are a patchwork of languages, ethnicities and political attachments.

This contrast is not surprising to those at least remotely familiar with Ukraine’s history in the twentieth century. The Centre of the country was the main arena of the Ukrainian independence struggle in 1917-1919 and the Western regions have remained outside of the Soviet sphere of influence until World War II. It did not take a lot of time in those parts of the country to revive the strong feeling of the national identity after the collapse of the Soviet Union, albeit sometimes this identity was built on outdated myths and perceptions more fitting in the nineteenth century context than in the modern day Europe.

The South and the East have been on a quite different trajectory: these thoroughly urbanized areas have more ethnically diverse populations with a significant share of working class—and for these people the fall of the Communist system left a much bigger void. Most of them had wholeheartedly embraced the idea of the new independent Ukraine initially, but after some time many felt (and still feel) alienated and unconvinced. These people are not compelled by the prospect of adopting a new set of ‘national’ heroes in place of the old Soviet ones that turned out disappointment – they need a new vision of the country’s future rather than its past. This vision must be inclusive and engaging, and until it is offered, the South East of Ukraine will be divided—not only from the rest of the country, but even more so within itself.

Therefore, the crisis in Ukraine is not a competition of two equally developed paradigms, pro-European and pro-Russian. Instead, it is a dual challenge faced by the country: while the West and the Center must find courage to break with some of the old dogmas and modernize the national vision to make it more compelling for the East and the South, the latter must step out of its lethargy and join efforts with the former in shaping the future of Ukraine. In other words, what we see is not a quarrel of ethnic groups, but a nation struggling to mature and find its unifying idea.

The encouraging news is that Europeanization seems to be a good candidate for such an idea. It is well known that recent protests in Ukraine started as an essentially pro-European movement, after the government abruptly decided to drop out of the EU association deal. It is less well known that the movement was not confined to Kiev only, or to the Center and the West of the country.

Reproduced from Wikipedia, color shows estimated number of people participating in local Euromaidan rallies in Nov 2013 – Feb 2014, dots show cities where mass protests took place

Even more importantly, all Ukrainians, regardless of the region they live in and language they speak, tend to demonstrate uniform and quite European attitudes on key “value-differentiating” issues. Recent recent polls show that, similar to people in Europe, Ukrainians put significant emphasis on the personal security and freedom, they attach more value to basic civil liberties than to economic stability, and at the same time believe the standard of living to be a more important issue than internal political divisions, they increasingly believe into the strengthened role of local governments and self-organization, and so on. This is a solid fundament for a constructive national dialogue and such a dialogue should be in the center of the today’s political agenda in Ukraine rather than tiresome and fruitless debates on historical and linguistic issues.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations