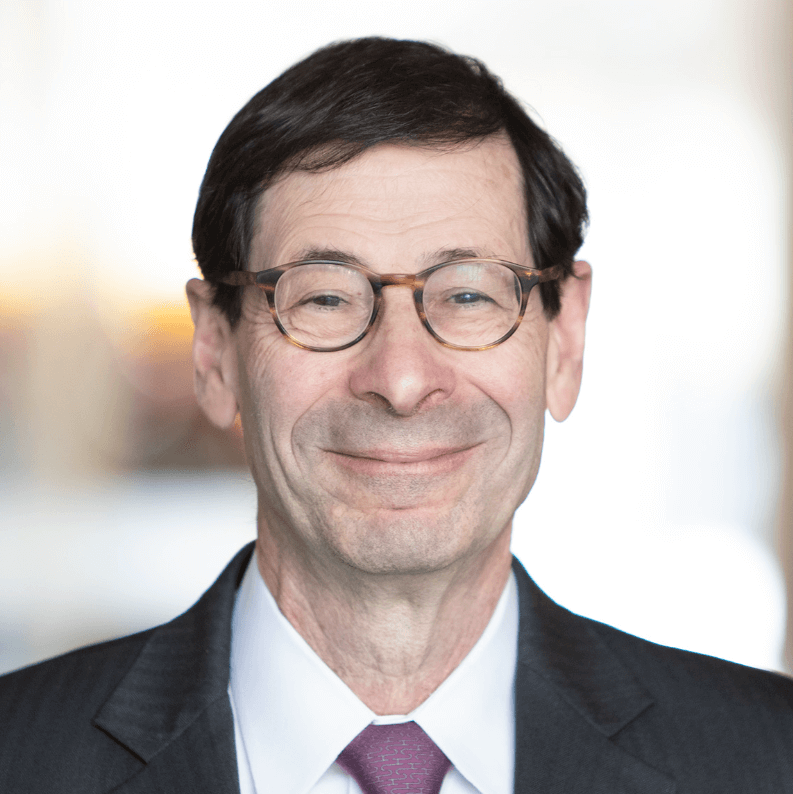

When Ukraine regained independence in 1991, its real GDP per capita was on a par with those of the more prosperous Eastern European economies of the former Soviet bloc (Figure 1). By 2022, Ukraine was one of the poorest countries in Europe. While there are many reasons for this dramatic reversal of fortunes for Ukraine, a durable ceasefire or peace agreement will initiate a new epoch in Ukraine’s post-Soviet development.

Figure 1. GDP per capita since the collapse of the Soviet bloc, 1990-2019

PPP = purchasing power parity

Source: Penn World Table

Apart from the immediate demands of damage repair and demobilization, Ukraine will need to overcome long-term structural challenges to the supply of key factors of production, as well as to ensure grants, loans, and other financial resources from abroad. Governance reforms in the public and private sectors will be a necessary complement.

The challenges may seem insurmountable, but as we argue in Gorodnichenko and Obstfeld (2026), there are good paths forward. Indeed, Ukraine is now perceived to be firmly in the West’s orbit, and therefore integration of Ukraine into Europe’s economic and security systems is a likely outcome. This would open many possibilities for economic development. The experience of Eastern European countries that joined the European Union, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), or both points to the possibilities. Foreign capital inflows, EU structural funds, and sustained investment, combined with institutional reforms, offer Ukraine a realistic trajectory to reconstruction and sustained income growth.

Many factors contributed to the growth miracles in Eastern Europe after the Soviet bloc’s dissolution, but the basic facts suggest a simple recipe: Productivity gains and physical capital accumulation played the key roles in the stunning rise of incomes. Improvements in human capital helped, too, but these were largely offset by depopulation trends.

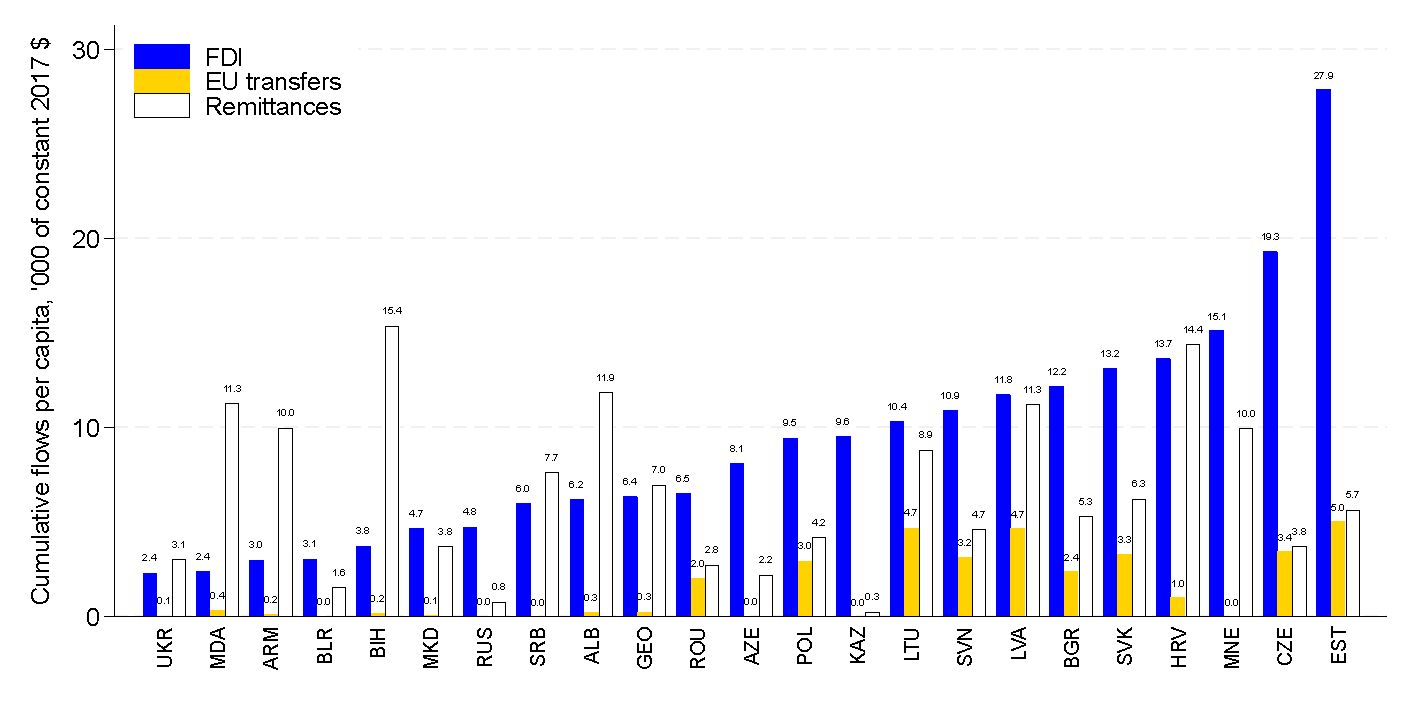

In our paper, we first document that new EU/NATO members were able to attract massive capital inflows via private foreign direct investment (FDI) and public structural funds. In contrast, countries outside the EU/NATO perimeter relied much more on personal remittances to finance domestic investment and consumption (Figure 2). While helpful, remittances clearly cannot provide the benefits of FDI: The data indicate that FDI and structural funds not only increase capital intensity (and thus raise incomes directly) but also facilitate technological upgrades and help retain population.

Figure 2. Cumulative international capital flows, 1990–2019

Sources: World Bank, European Commission, Eurostat, International Monetary Fund

Second, we show that the mere prospect of joining the European Union and/or NATO can spur capital inflows even before accession formally takes place. Intuitively, the European Union offers market access and financing while NATO membership has made countries investable by providing credible (at least up until now) security guarantees. If the probability of accession is high, private businesses can launch investments as a beachhead for future operations in the country well before the ink on the treaties is dry. For example, German Volkswagen acquired an equity stake in Czech Škoda in 1991. That was years before Czechia joined NATO or the European Union but after the European Union launched a program to help Czechia and a few other prospective member countries attract foreign investment. Volkswagen fully acquired Škoda in 2000, a year after Czechia joined NATO and four years before it joined the European Union.

Third, the European Union and NATO can provide institutional anchors to accelerate reforms and to ensure political and economic stability. These considerations are particularly important in the Ukrainian context, as the country has gone through three revolutions and experienced dramatic macroeconomic volatility. Because a stable environment makes a country more attractive to foreign capital, stronger institutions can create a virtuous circle: More investment improves the economy, thus making the country more stable and resilient to shocks; greater stability, in turn, attracts investment.

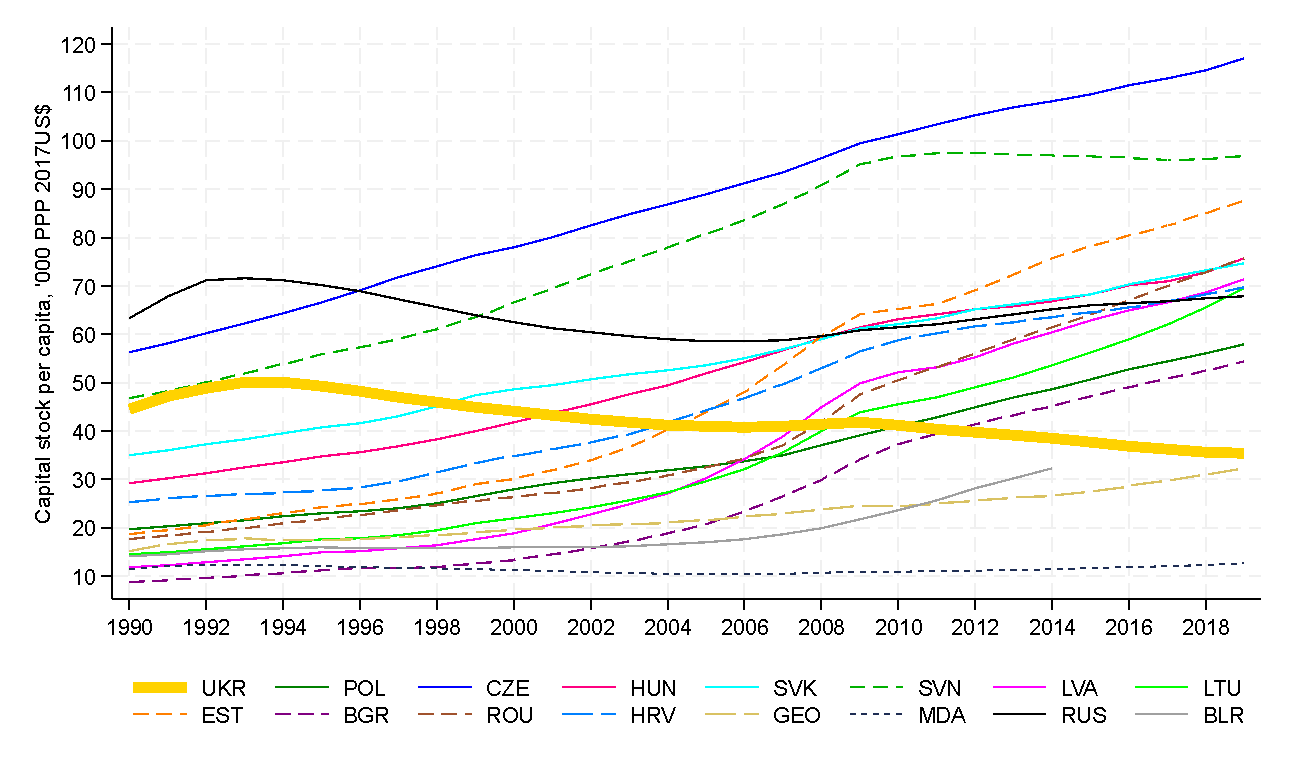

Perhaps, not surprisingly, capital intensity has been declining in Ukraine since early 1990s, while Eastern European EU members experienced dramatic capital deepening (Figure 3). In fact, capital deepening over 1990–2019 was the main feature that separated EU/NATO members from countries that did not join these organizations. While Ukraine and Moldova relied on personal remittances to finance their consumption and investment, Poland and Czechia received massive private capital inflows and public structural funds. Furthermore, those investments facilitated technology transfer and helped address demographic issues by making the countries more attractive to live and have a family.

Figure 3. Capital stock per capita.

PPP = purchasing power parity

Sources: International Monetary Fund, Penn World Table

We argue that the strategy focused on capital deepening can be further refined to attain even better results. Specifically, we develop three models of optimal economic growth. Each of these models focuses on a key aspect of investment to build intuition and keep the analysis tractable. First, we consider the implications of foreign borrowing constraints, which are likely to be particularly binding for postwar Ukraine. Second, we investigate how investments in human and physical capital interact to understand their optimal mix. Third, we examine the interplay between capital deepening and population flows to explore how higher investment can induce Ukrainian war refugees abroad to return.

We show theoretically that investment in physical capital can generate benefits that may not be internalized by market actors. For example, investment in physical capital relaxes borrowing constraints (thus allowing more capital inflows) and raises wages (thus encouraging more Ukrainian refugees to return home). The government can achieve superior outcomes by policies that steer more resources into investment. We model such policies as a consumption tax that declines over time as the country accumulates more capital. Furthermore, there is a potential need for a permanent investment subsidy (equivalently, a permanent saving subsidy) to correct market myopia. Of course, such policies can be implemented through a variety of tools. In addition to taxes (or tax exemptions), financial repression, regulation, capital controls, and other standard instruments, Ukraine can rely on complementary strategies to de-risk investments such as providing war insurance, loan guarantees from donor countries, and public-private partnerships.

Our analysis suggests that, in addition to deep foreign debt restructuring, Ukraine needs at least $40 billion per year in new investment from external sources and domestic saving: $20 billion for rebuilding the capital stock, $10 billion for keeping Ukraine from falling further behind in capital intensity, and $10 billion to launch modest convergence toward EU peers. This estimate obviously is provisional, and the magnitude can vary depending on the course of the war (for instance, if more capital is destroyed, the gap between gross and net investment will be smaller than in a steady state because with little preexisting capital, there is little to depreciate).

Will the strategy that worked in Poland and Czechia work for Ukraine? Ukraine’s past failure to attract FDI illustrates the costs of unreformed judicial power, weak property rights, corruption, oligarchic rule, and an unstable macroeconomic environment. None of these factors is impossible to address, but it is the homework that only Ukraine can do.

Yet despite Ukraine’s record of missed opportunities, we believe this time will be different. The existential threat to Ukraine emanating from Russian aggression and the prospect of Ukraine joining the European Union—and, as Ukrainians joke, perhaps one day NATO will join Ukraine—are a powerful combination of sticks and carrots. There is an overwhelming consensus in Ukrainian society that the European Union is the only civilizational choice for Ukraine. This sentiment creates a mighty force that can overcome vested interests and political differences to thoroughly modernize the country. No less importantly, Europe now views Ukraine as part of Europe rather than a Russian sphere of influence or a buffer state. Thus, both sides demonstrate serious interest in making things happen. Ukraine’s chances will be better, of course, if the European Union raises its own ambition and unity in the face of a triad of threats from a hostile Russia, a revisionist China, and a commercially aggressive but militarily unpredictable United States.

This historic opportunity may be the last chance for Ukraine to survive and prosper as a sovereign nation. You only live twice.

Photo: depositphotos.com/ua/

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations