VoxUkraine and PACT implemented the Applied Political Economy Analysis (APEA)[1] of civil society anti-corruption activities in Ukraine. The project was motivated by the importance of anti-corruption agenda for our country. First, the problem is really urgent. Second, high-level officials do not exhibit much dedication to combating corruption. Therefore, civil society has to assume one of the key roles in reducing the scale and opportunities for corruption[2]. The project’s aim was thus to find out the incentives and constraints of anti-corruption civil society organizations (CSOs) in Ukraine and see how these differ for national-level (Kyiv-based) and subnational (regional) civil society groups.

In April-May 2016, we performed in-depth interviews with 61 representatives of anti-corruption (AC) organizations and 33 public officials in Kyiv, Lutsk, Rivne and Zaporizhzhia (see survey methodology). Selected regions show the highest level of anti-corruption civil activity.

Social Network Analysis (SNA)

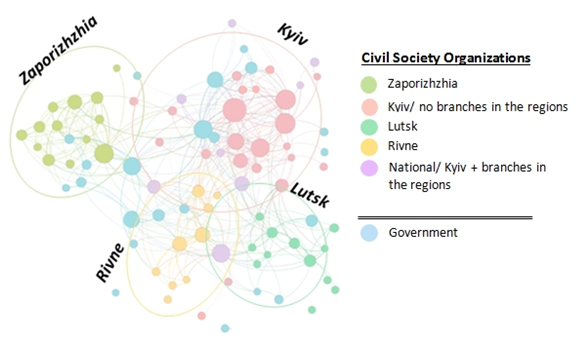

Before turning to incentives and constraints, we analyzed the links between AC organizations to determine (1) how influential they are and (2) how intensively they cooperate with each other and with the government bodies. The results of this analysis are presented as the SNA map (Figure 1). The nodes represent the AC actors, while the edges represent the number of times the actors mentioned each other in different context (i.e. answering the questions with whom they cooperate, whom they know etc). The size of the nodes is proportional to the impact factor of the organizations. It shows how popular or influential an organization is — i.e., how often it was mentioned by other organizations or government officials.

Figure 1. Key AC actors in the regions interviewed by VoxUkraine

Each node is associated with a particular actor (CSO or government body) and its size is proportional to its impact factor. The CSOs are colored by the region of location; the “national” designation means that the CSO has branches in the regions or acts at the national level (see the detailed methodology).

Figure 1 demonstrates several facts:

- Kyiv-based organizations operating at the national level are better-known than local organizations (an expected result since they have many more resources). We think that if we had conducted field studies in other regions, the impact factor of Kyiv and national CSOs would have increased.

- There is close cooperation between local-level organizations located in one region, but practically no cooperation between CSOs in different regions[3]. At the same time, many regional CSOs mention Kyiv-based CSOs in some context (either as those providing consultations/trainings, or as influential AC actors etc).

- AC organizations in Zaporizhzhya are on average more influential than those in Rivne and Lutsk;

- CSOs in Zaporizhzhya have close ties between themselves but practically no links to CSOs in other regions, and just a few links to Kyiv-based organizations. Organizations in Rivne and Lutsk have dense ties with Kyiv and nation-wide organizations, although not many significant interregional ties.

- The most widely known AC organizations act at the national level (e.g., lobbying for legislation) and don’t have regional branches. Generally, quite a few initiatives have regional offices — and mostly these are not purely AC organizations but either media outlets or organizations involved in the supervision of elections. Kyiv-based national-level organizations closely cooperate with each other but not with the regional organizations. However, national-level organizations which have branches in the regions cooperate with local organizations, and this cooperation is more evident in Rivnenska oblast.

- Government bodies on average have smaller impact factors than CSOs – they are less often mentioned among AC players.

The survey also showed that CSOs are known much more widely than individuals working in these organizations. When asked about key AC entities in their regions, about 90% of respondents named organizations rather than individuals. Some respondents named both organizations and their leaders. But the fact of brand-building by organizations suggests that they may be more stable than we previously expected. It is good to see that their strategy is developing as institutions rather than centering themselves around individuals.

Types of CSOs

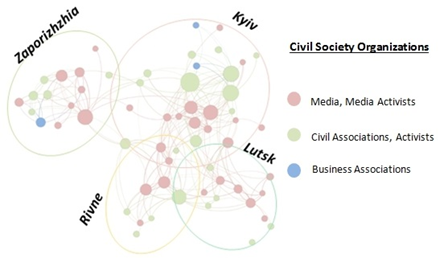

We identified 3 types of CSOs (figure 2):

- media-activists (30 respondents) conduct anti-corruption investigations and make them available to civil society through local and national media;

- civil associations/NGOs (28 respondents), are involved in advocacy, monitoring, information campaigns and consultations on various anti-corruption issues;

- business associations (3 respondents) specialize in business-specific AC issues.

Figure 2. CSO types

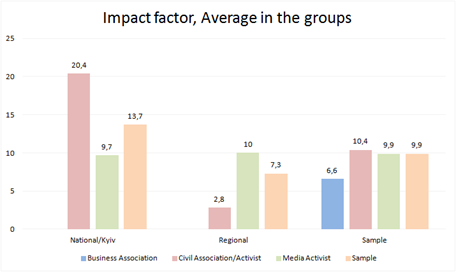

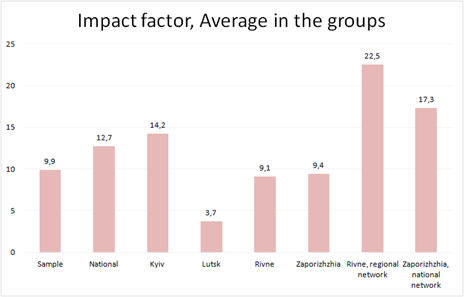

Figure 2 shows that on the national level citizens’ organizations (NGOs) are more influential than media activists, while on the regional level the opposite is true. Figure 3a shows the same fact but in a more convenient form – we see that impact factor of CSOs at the national level (20.4) is much higher than that of media activists (9.7), while on the regional level the relation is reversed (2.8 vs 10). We think that this can be explained by the high visibility of national-level CSOs both in media and in social networks, while local-level organizations may not have the capacity or resources for promoting themselves.

Figure 3b shows that CSOs entering networks have much higher impact factors than individual CSOs, even of the national level.

Figure 3a

Figure 3b

Activities of CSOs

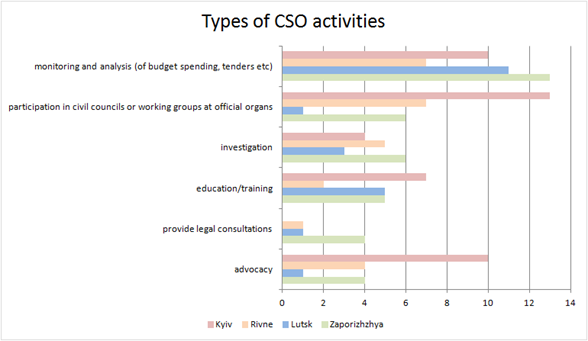

CSO representatives and individual activists were asked to name the types of activities they are involved in (Figure 4). The majority are involved in monitoring (of budget spending, tenders etc.), less so in advocacy and other activities. Some organizations, mostly from Kyiv, analyse draft laws or even compile draft laws and advocate for their adoption. On the local level, quite a few CSOs participate in drafting documents of local administrations. In Kyiv and Rivne relatively more CSOs try to impact decision-making of officials via formal mechanisms — participation in civil councils and working groups at local government bodies. Nevertheless, the majority of CSOs admit that a lack of cooperation on the side of authorities is one of the main constraints to their activity.

Figure 4. Activities of surveyed CSOs

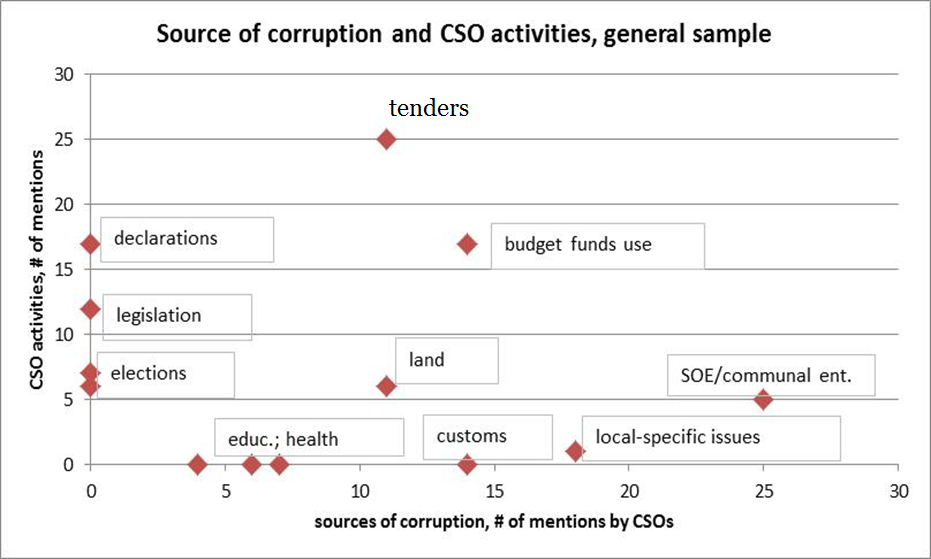

We also looked at the correlation between spheres which CSOs believe to be the primary sources of corruption and spheres in which they operate (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Sources of corruption and CSO activities

We do not see much correlation here and we think that this is because CSOs weigh things that they are willing to do with things they are capable of doing (e.g. if they have access to some insider information, they may be more inclined to do investigations; if they have access only to publicly available data, they may stick to data analysis etc). We noticed that very few AC activists are engaged in the most problematic areas – such as scrap metal trading in Zaporizhzhya region and illegal amber mining and smuggling in Volyn region. These spheres are supposedly controlled by high-level officials and organized crime, so it would be too dangerous for activists to actively engage into them.

The majority of regional CSOs are involved in monitoring of the usage of budget funds (central or local budgets), tenders or declarations of officials. The second most popular activity of CSOs is advocacy – expertise and advice on national-level and local-level legislation. This activity is more frequent among national-level CSOs. Some CSOs provide AC trainings and legal advice.

The core question of our project was:

What are the incentives and constraints for CSOs to effectively engage in AC activities at the national and regional levels?

The answer is as follows:

The main incentive of AC organizations is similar on the national and regional levels – and it is making impact (alternatively – changing the country) – a motivation that can arise both from personal ambitions (desire for self-realization) and from the feeling of responsibility. Other incentives are money received from donors (international organizations) or from some interest groups, e.g. some businessmen or politicians can use AC organizations to defame their competitors. However, as long as actual cases of corruption are revealed, we do not care much about the reasons behind them.

The main constraint (and it is more pronounced on the local level) is disproportionately little result of AC effort – e.g. very few corrupt officials are punished, and those punished are mostly low-level officials; old corrupt practices prevail in most of the spheres, and the general public seems to be OK both with petty corruption and with grand corruption. This situation is very discouraging for AC activists. To reduce this constraint, a deep law-enforcement and judicial system reform is needed. Another noticeable constraint is poor cooperation with the civil society on the side of officials, especially in Volyn region, and pressure on activists (threats, physical offences etc). Personal pressure on activists is the highest in Zaporizhzhya and the lowest in Kyiv because Kyiv-based CSOs usually act at the national level and so (1) they have more resources and are more independent, and (2) they are more visible and thus can more easily employ popular and international support.

Policy recommendations

Taking into account these findings, our primary recommendation would be to develop a network of CSOs where national-level and local-level organizations and activists could communicate, exchange experience or advice. In fact, such cooperation platform has already been created.

Next, we recommend to involve the private sector (i.e., businesses) more into AC activities, since SMEs are the primary beneficiaries of reduced level of corruption.

Third, we recommend training CSOs to use crowdfunding and to involve general public into their activities.

Finally, mechanisms of cooperation between officials and civil society should be formalized and strengthened (i.e. officials should be made responsible for non-cooperation) to enhance the opportunities for CSOs to impact the national-level and local-level decision-making.

Notes:

[1] Applied Political Economy Analysis: A Tool for Analyzing Local Systems. A Practical Guide To Pact’s Applied Political Economy Analysis Tool For Practitioners And Development Professionals, September 2014

Project Team:

PACT team: Marc Cassidy, Yulia Kurnyshova

VoxUkraine, Kyiv: Tetyana Tyshchuk, Ilona Sologoub, Natalia Shapoval, Ksenia Alekankinal, Kyrylo Iesin, Maksim Skubenko, Yaroslav Kudlatskiy, Maksim Mamedov, Ihor Sheheda

Regional experts: Yurii Dyug (Rivne), Maya Golub (Lutsk), Natalia Vigovska (Zaporizhzhya)

[2] To find out whether civil society in general can be an efficient anti-corruption player, we reviewed the academic studies on the impact of CSOs on the level of corruption in different countries. The main result of this review (which is provided in the Appendix 1) is that the best results are achieved when efforts of civil society and the government are combined and that press freedom is crucial for success of anti-corruption activities of civil society.

[3] In fact, a few CSOs indicated the need for more extensive communication not only between national and local CSOs but also between CSOs from different regions for the purpose of sharing their experiences in AC activities.

[4] However, many media activists report that law enforcement authorities mostly go after small-scale corrupt officials while “the big fish” remains in the water.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations