This requires punishing Russia for breaching international law, the first step to which is arming Ukraine.

Recently, the Russian parliament discussed the possibility of denouncing the so-called “Shevardnadze-Baker agreement” on the maritime boundary between the USSR and the US. The Russian parliament is “not a place for discussions” (according to its former Speaker), so this was a signal from Putin to the world about Russia’s expansionist plans—this time in the Arctic. These aspirations were clearly expressed in the 2022 Russian maritime doctrine proclaiming its interests in the Arctic waters and resources.

Russia’s military capacity is largely depleted in Ukraine, so now is a favorable moment for NATO to show its strength and limit Russia’s Arctic ambitions. This will have long-term benefits for the planet since preserving the Arctic is essential to slow down global warming.

What is at stake?

The Arctic accounts for about 22% of the world’s undiscovered oil and gas resources and abundant known resources. Apart from oil and gas, these include iron ore, coal, phosphates, rare earth and precious metals, gemstones, and diamonds. There is some hunting by indigenous groups, and abundant stocks of fish such as cod, pollock, and redfish. Arctic fisheries generate about $560 million per year, and this number may increase thirty-seven-fold due to ocean warming.

Limiting human activity in the Arctic region is in the interest of the entire world. Ironically, countries very far from the Arctic, such as Barbados, will suffer the most from climate change and thus have the largest interest in its preservation. The Arctic can be protected only by international laws that take into account the interests of all nations and disallow predatory behavior. Russia and its allies, such as Iran and China, have no respect for international law and need to be coerced into compliance.

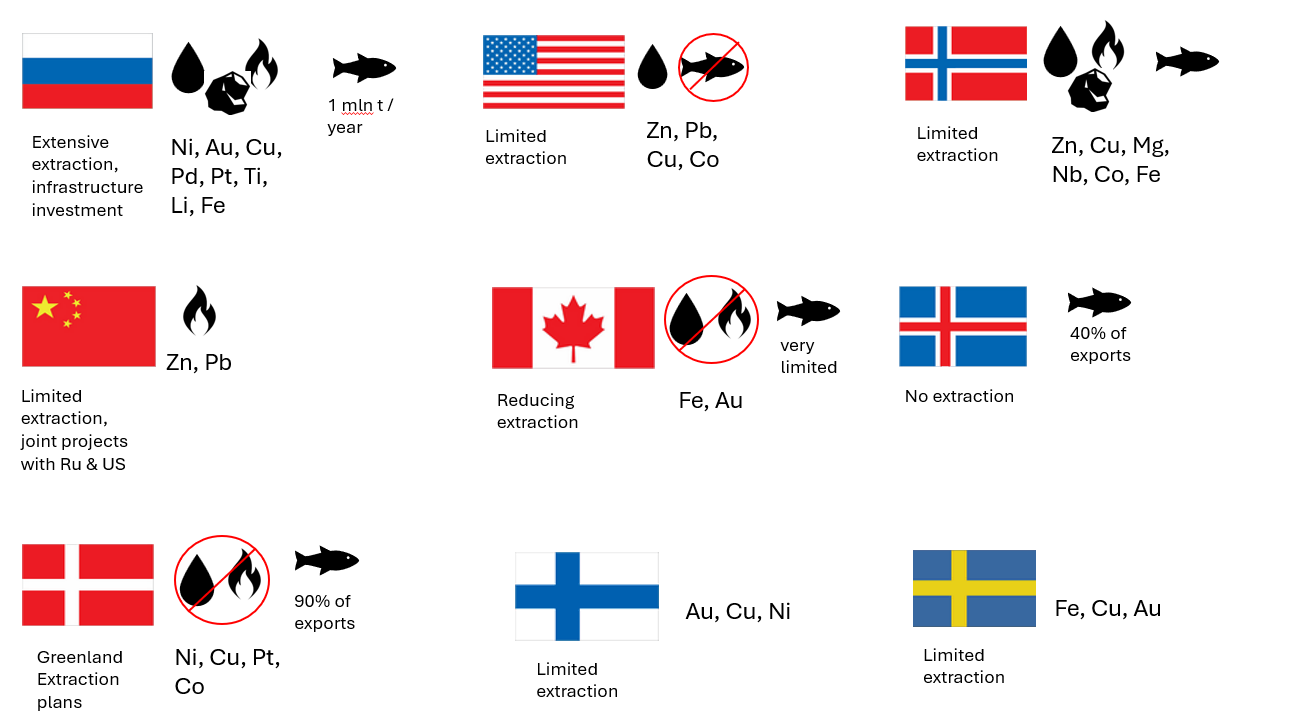

Who exploits the Arctic?

As shown in Table 1 and Figure 2, Russia exploits Arctic resources most extensively: it extracts hydrocarbons, mines, fish, and uses the Northern Sea Route to transport LNG. It is one of a few countries that will actually win from global warming: if cleared of ice, the Northern Sea Route would be 6000 kilometers shorter than the current route from Shanghai to Rotterdam, mostly along the Russian coast (and the current situation in the Red Sea clearly shows how international shipping lanes can be weaponized by malicious actors). Global warming would also open up the Arctic to greater exploitation of its natural resources, which is why Russia already invests so heavily there today. Russia’s economic and military presence in the Arctic are closely aligned. One prominent example is the Barentsburg mining town on the Norwegian peninsula of Svalbard. Russia has been operating there at a loss for decades to keep a few hundred Russians on the peninsula — so Russian intervention could be justified by the “protection of its citizens.”

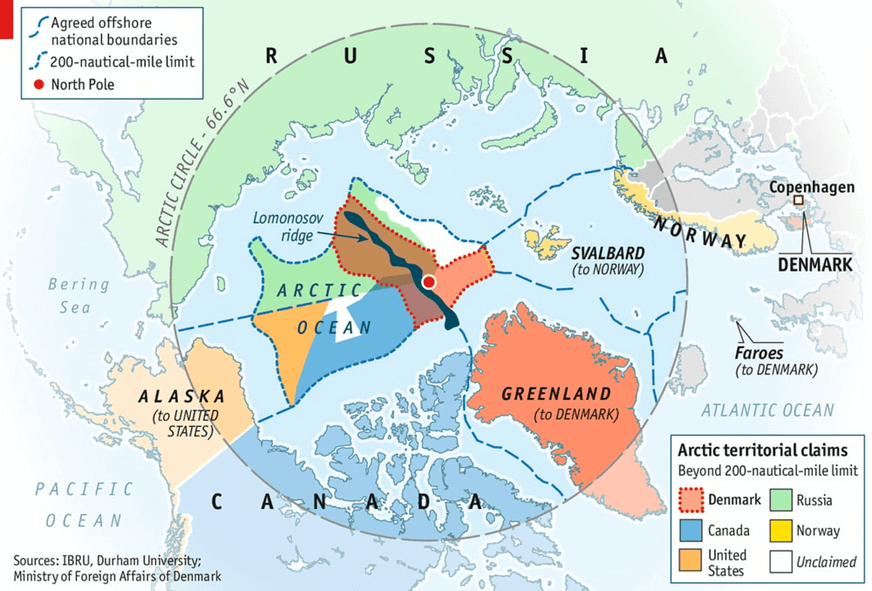

Figure 1. Countries (potentially) exploiting resources within the Arctic Circle (above 66⁰ N)

Source: The Economist

How is the Arctic regulated?

Under the UN Convention of the Law of the Sea, countries have an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) to exploit natural resources within 200 nautical miles of their coastlines. Exclusive rights over the seafloor may extend even further than the EEZ as part of the Extended Continental Shelf (ECS). Under these claims, resources in the Arctic Ocean may be exploited by Canada, Greenland (Denmark), Iceland, Norway, Russia, and the United States (Figure 1).

In 1996, these countries, together with Finland and Sweden, founded the Arctic Council to promote scientific cooperation and preserve the environment and culture of indigenous people. In addition to the eight Arctic nations, thirteen countries had observer status on the Arctic Council. China, in particular, has expressed an interest in the region, referring to itself as a “near-Arctic state” and developing a “Polar Silk Road” in Russia’s Northern Sea Route as part of the Belt and Road Initiative. The Arctic Council ceased to function in 2022 due to Russia’s aggression against Ukraine.

Given its global importance, many countries try to preserve the Arctic: Canada, the US, and Norway limit the extraction of natural resources there, and the US and Canada also limit fishing. In 2021, an international treaty placed a moratorium on commercial fishing in the Central Arctic Ocean until 2037. While this ocean is mostly covered in ice and not part of any country’s EEZ, commercial fishing could increase there in the future as ice caps melt. Apart from the six Arctic coastal states, the treaty was signed by China, Japan, South Korea, and the European Union.

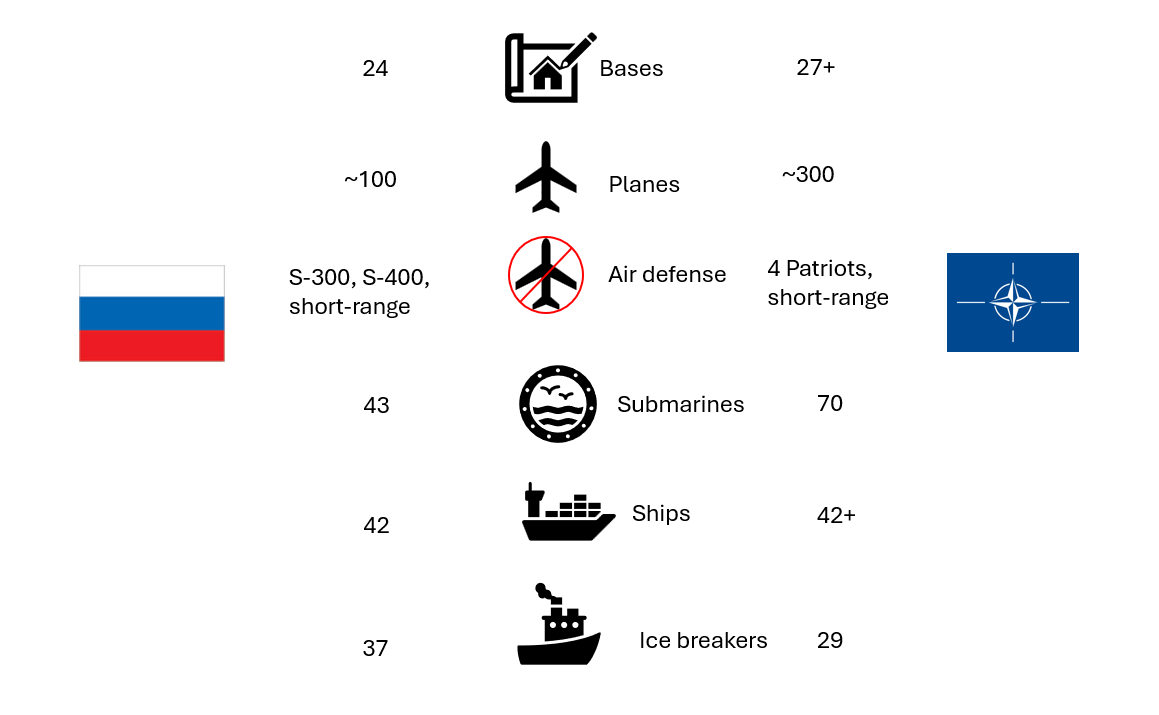

Russia vs. NATO in the Arctic

In 2013, Russia established OSK Sever (the Northern Fleet Joint Strategic Command) to “defend” the Arctic (Russia’s ultimate goal is to phase out NATO from the region). Thus, the Arctic became one of five Russian military districts. It has five operational formations: the Submarine Command and fleet, the Kola Flotilla, the 61st Naval Infantry Brigade, the 45th Air and Air-Defenses Army, and the 14th Army Corps. In addition, Russia holds four major air units in the Arctic with about 100 aircraft and a fleet of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), some ground equipment such as tanks and armored vehicles, and a large number of radars and other surveillance equipment.

Russian Arctic forces are still considerably weaker than combined NATO forces in the region (see Table 2 and Figure 3). For example, NATO countries have at least three times more aircraft than Russia (and those are of much better quality). The same applies to submarines. Although NATO countries have fewer ships and icebreakers in the Arctic region, Ukraine has shown that the number of ships is no longer a decisive factor in war: large and expensive ships can be easily sunk by much cheaper maritime drones (Russia is investing in underwater drone technology, which is unlikely to be in place before the 2030s or 2040s).

Ukrainians have also shown how Russian air defense systems such as S-300 or S-400 (many of which are stationed in the Arctic) are ineffective against missiles such as the Storm Shadow. Furthermore, many of the Russian army units previously based in the Arctic were transferred to Ukraine and sustained heavy losses there (they fought near Luhansk in 2014, in Bucha and Kherson in 2022, and in Bakhmut and Tokmak in 2023). Production of additional ships and icebreakers for Russia’s Northern fleet is delayed because of sanctions (plus, Russia destroyed the Ukrainian plant that was supposed to deliver some of the parts).

Nevertheless, Russia continues its saber-rattling in the region. In 2023 it conducted four major rounds of military exercises in the Arctic: in January, April, August, and September, and in September 2022 it implemented joint exercises with China. NATO (including new NATO members) extensively exercised there as well: in 2023 there were training sessions in February-March, May and June. Sometimes, these exercises risk escalation. For example, Russia often organizes army training near the borders or EEZs of other countries. Incidents with surveillance aircraft occur frequently and are not seen as provocative, but occasionally the situation gets more serious: in 2018, eleven Russian supersonic jets practiced a “mock attack” on Norwegian military surveillance radars, and in 2021 two NATO jets had to intercept Russian fighter jets in international airspace over the Barents Sea.

If these incidents continue, it is only a matter of time until one of them leads to a serious escalation. If encouraged by the weak response from other states, Russia may even deliberately escalate. A military conflict in the region would have dire consequences for the world, even for countries that are far away from the Arctic. Thus, the international community must become far more serious about counteracting Russia. This can be achieved by arming Ukraine faster and more intensely, because deterrence in Ukraine will prevent Russia from attacking elsewhere. The world needs to clearly show Russia (and its allies) that it has to follow international law — before Russian imperialism further endangers the planet through aggression on the Arctic.

Figure 2. Extraction of Arctic resources by country

Source: compiled by authors based on Table 1

Figure 3. Russia and NATO military presence in Arctic

Source: compiled by authors based on Table 2

Table 1. Exploitation of Arctic resources

| country | hydrocarbons | metals | fishing |

| Russia | Russia accounts for over 90% of oil and gas extraction in the Arctic (35,700 billion cubic meters of natural gas and 2,300 metric tons of oil and condensate per year). Most of this oil and gas production is concentrated around the Yamal and Gydan Peninsulas.

Nearly 90% of undiscovered Russian gas is offshore, such as the undeveloped Shtokman field in the Barents Sea. Russia invests heavily in this industry: in 2020, the Russian government implemented $300 billion in tax cuts and incentives for new ports, factories, and oil and gas projects in the Arctic. Exxon Mobil left a joint venture in the Kara Sea due to sanctions introduced in 2014 but in 2020 Rosneft restarted drilling. Now it is seeking investment from India and China for the giant Vostok Oil project in the northern Krasnoyarsk Territory, aiming to produce more than 100 million tons of oil and 50 million tons of LNG per year. Oil and gas are shipped to consumers in the East and West by pipelines and the Northern Sea Route using nuclear ice-breakers. While the world is reducing coal extraction, Russia is planning to develop new coal mines in the far north. It maintains a presence on the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard through a small coal mine in the town of Barentsburg, despite operating at a deficit for decades. |

The Russian Arctic contains an estimated two trillion dollars’ worth of minerals, including rare earth elements. Russia extracts gold and diamonds in the region. It also mines apatite-nepheline ore in the Arctic Khibiny Mountains.

Huge Arctic nickel deposits such as Norilsk-Talnakh and Zhdanovskoye help make Russia one of the world’s leading producers of nickel. It also produces significant quantities of copper, palladium, and platinum from these deposits. Russia plans to build its largest lithium mine on the Kola Peninsula to create a battery production industry. China Communications and Construction Co. is cooperating with Russia to mine its largest titanium deposit. The Pizhemskoye field in the Komi Republic also contains zircon, iron ore and gold. As part of the project, they will construct a new railroad and seaport. |

About one-third of all fish harvested in Russia (about 1 million metric tons per year of cod, haddock, pollock, capelin, herring, grouper, and mackerel) comes from Arctic waters. The Russian government hopes to increase that share as the ocean becomes warmer and fish migrate to the North.

80% of fish stocks are in the Barents, White, Norwegian, and Greenland seas. Russia also fishes in the Kara, Chukchi, and Laptev Seas, but this amounts to less than a thousand tons per year. Over 50% of Russia’s fish export is pollock, followed by cod and herring. |

| US | President Biden has limited oil and gas leasing in the Alaska National Petroleum Reserve and placed a moratorium on drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. He also banned offshore drilling in most or all US Arctic waters (the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas).

Oil production has been in decline in Alaska, especially as many companies have pulled out of the region for financial, technological and legal reasons. However, in 2023 Biden approved the Willow project to drill oil on the North Slope of Alaska, inside the National Petroleum Reserve. |

The Red Dog zinc and lead mine in the Alaskan Arctic is one of the world’s largest producers of zinc. China Investment Corporation (CIC) has a 10% stake in the company that operates the mine.

There are projects in development to mine copper, zinc, lead, cobalt, gold, and silver in the Alaskan Arctic. While rare earth metals occur in Alaska, they are not being mined. Neither is gold. |

The US Arctic has been closed to commercial fishing since 2009. |

| Norway | Norway only drills oil and gas offshore.

In the Barents Sea, Norway produces oil in the Goliat field and natural gas in the Snøhvit field. The Johan Castberg field should start oil production in 2024. Arctic drilling accounted for about 2% of Norway’s oil and gas production in 2022 (the majority of its hydrocarbon extraction lies outside the Arctic). In 2023, Norway offered 78 exploration blocks in the Barents Sea to energy firms. Norway’s state-owned coal company plans to continue mining coal in Svalbard until 2025 “to help ensure supplies to European steel-makers at a time of war.” |

Norway opened the Arctic Ocean to seabed mineral exploration in 2023 after finding “substantial” resources on its extended continental shelf, including copper, zinc, magnesium, niobium, cobalt, and rare earth metals.

Swedish and Norwegian companies operate large iron ore mines in Norway. |

Fish is Norway’s “second most important export product after oil.”

Norway’s Arctic fisheries (in the Norwegian and Barents seas) are rich in cod, haddock, saithe, and shrimp. Norway and Russia renewed a fisheries agreement dividing fish quotas in the Barents Sea. However, Norway banned Russian fishing vessels from all ports except Tromsø, Båtsfjord and Kirkenes in the Arctic. Svalbard is the world’s northernmost location with regular fisheries. The EU is allowed to fish for cod in the area, while Iceland and Greenland can fish for shrimp. |

| Canada | Canada banned all offshore oil and gas drilling in the Arctic in 2019. Almost all of their oil and gas production is not in the Arctic. | Canada mines iron ore and gold within the Arctic. But it limits the expansion of this mining. | Arctic fisheries in Canada remain small relative to fisheries in other parts of the country because of difficult geographical conditions (these will improve with global warming). Most commercial fisheries are in the Eastern Arctic (Baffin Bay, Davis Strait, Hudson Bay) and target Greenland halibut, groundfish and Northern prawns.

Canada placed a moratorium on commercial fishing in the Beaufort Sea and a ban on all foreign fishing in its Arctic region. |

| Iceland | So far Iceland does not extract oil or gas but exploration could open in offshore areas. | To the best of our knowledge, Iceland doesn’t mine metals in the Arctic. | Marine products account for 40% of Iceland’s exports. This includes cod, haddock, capelin, herring, and redfish. It’s difficult to say how much of this fishing occurs within the Arctic (off the northern coast of Iceland).

Norway and Greenland are allowed to fish in Iceland’s waters. |

| Denmark (Greenland) | Greenland ended oil and gas exploration in the Arctic in 2021. | Despite having “potentially abundant” rare earth minerals, as well as iron ore and zinc, Greenland has only two operating mines, producing anorthosite and rubies. British mining giant Anglo American has an exploration license for nickel on an island in Greenland, as well as prospecting licenses covering thousands of square kilometers in west Greenland. British company Bluejay Mining formed a joint venture with US-based KoBold Metals to develop a mining project for nickel, copper, platinum and cobalt. A Canadian company plans to develop a rare earth mineral mine in Greenland.

China made several attempts to invest in mining projects in Greenland. However, the US warns against such involvement and proposes alternative financing. |

Fish products account for 90% of Greenland’s exports, especially prawns and Greenland halibut. Fishing activity is mainly concentrated in southern Greenland, below the Arctic Circle. In the Arctic Greenland fishes for herring.

Greenland halted a fisheries agreement with Russia for 2023. The agreement previously allowed the countries to swap fishing quotas, with Greenland fishing for cod and haddock in the Barents Sea of the Russian Arctic and Russia fishing for halibut and redfish in Greenlandic waters. It’s unclear if the agreement was renewed for 2024. |

| Sweden | Sweden imports oil and gas and develops green energy. | Sweden is part of the Fennoscandian Shield of mineral deposits, making it an important mining area for the EU: 80% of the EU’s iron ore comes from the Kiruna mine in the Swedish Arctic.

Sweden’s northern regions have iron ore, gold, and copper. The Aitik mine is one of the most efficient copper mines in the world; it also produces gold. |

Fishing accounts for about 0.1% of Sweden’s GDP and employs slightly over 1000 people. |

| Finland | Finland imports oil and gas. | The Kittilä mine in Finland is the largest gold mine in Europe, operated by a Canadian company. A copper-nickel mine is operated by a Swedish company in northern Finland. | Finland’s fishing industry is relatively small, and it mostly fishes in the Baltic sea. |

| China | China has been drilling gas in the Kara Sea in recent years. It also has joint projects with Russia: the Yamal LNG terminal in Russia was financed by the Export-Import Bank of China and the Chinese Development Bank, and Chinese companies have a 30% stake in the project. | China Investment Corporation (CIC) owns a 10% stake in the Red Dog zinc and lead mine in Alaska.

It also made several attempts to invest in mining projects in Greenland. |

China supported the CAOFA treaty because it allowed them to be a key stakeholder (rather than just an observer) in Arctic Council decision-making, and because their fishing interests in the Arctic were minimal. There was no Chinese commercial fishing in the Central Arctic Ocean prior to this. |

Table 2. NATO and Russian military presence in the Arctic

| Russia | NATO | |

| Military bases | 20 bases within the Arctic Circle: 9 military bases, 13 airfields, and 4 naval bases (some serve more than one function).

4 near-Arctic bases: 1 military base, 2 airfields, and 1 naval base. Additionally, there are 10 radar stations, 20 border outposts, and 10 emergency rescue stations. Two of Russia’s Arctic Brigade bases are located just a few kilometers from the Norwegian and Finnish borders. Electronic or electromagnetic warfare centers at Severomorsk, Kamchatka, and Primorsky Krai “could facilitate anti-submarine warfare and interfere with maritime communications.” |

16 bases within the Arctic Circle (of which 12 belong to Norway): 6 military bases, 8 airfields, and 3 naval or coast guard bases (some serve more than one function).

11 near-Arctic bases: 3 military bases, 5 airfields, and 3 coast guard bases (of these 9 belong to the US). In December 2023, the US and Finland signed a defense cooperation agreement allowing the US to use several Finnish bases (of these a border guard base, a military training base, and an airfield are within the Arctic). A similar agreement with Sweden allows the US to use one Swedish base in the Arctic and two airfields nearby. |

| Missiles | Much of Russia’s second-strike capabilities are located in the Arctic, including launch platforms for Kinzhal ballistic missiles. The Northern Fleet reportedly holds 20 percent of Russia’s precision strike capability in peacetime.

There were several missile tests in the Arctic in 2023, including ICBMs, ballistic missiles, and cruise missiles. |

Finland can use US AGM-158 JASSM air-to-surface missiles

In 2022 the U.S. tested the new “Rapid Dragon” weapons system, which uses long-range cruise missiles. Generally, NATO conducts far fewer missile tests in the Arctic than Russia. |

| Surveillance systems | There are Rezonans-N radar systems on Novaya Zemlya, the Kanin Nos Peninsula and Indiga, and Sopka-2 radar systems at the Temp, Nagurskoye and Rogachevo air bases.

Russia also has Arctic-specific satellites such as Meridian-M communications satellites and an Arktika-M weather satellite for navigation support. |

NORAD: Canada-US command that continuously provides worldwide detection, validation, and warning of a ballistic missile attack on North America.

The US operates satellite command and control stations and more than 50 early-warning and missile defense radar systems across Alaska, Canada and Greenland. Modernization of the surveillance systems is planned. Canada operates the North Warning System (which includes radars and unmanned systems) and a signals intercept intelligence facility (CFS Alert). It also plans to enhance its surveillance capabilities in the Arctic. Norway: 4 satellites to help monitor the Arctic. It is launching four more, two in 2023 and two in 2024. Sweden, Canada and Norway are planning Arctic spaceports. Sweden and Finland are investing in surveillance and deterrence capabilities, and Denmark is investing in satellites and surveillance drones. |

| Aircraft | Russia has about 24 Su-33 fighter jets, 24 MiG-29K fighters, 12 MIG-31BMs, 12 Su-24Ms and an indeterminate number of Su-24MR reconnaissance aircraft in the Arctic, as well as maritime patrol aircraft like the Il-38N and Tu-42.

Before the full-scale war with Ukraine, the Northern Fleet had about 30 bombers such as Tu-95 and Tu-160. |

US: 54 F-35s, two squadrons of F-22 jets, and a few surveillance aircraft in Alaska. US Navy P-8 Poseidon reconnaissance aircraft are also stationed in Iceland. The Air Force receives around 80% of all US Arctic military spending.

Norway: 6 P-3 Orion long-range maritime patrol aircraft, 4 C-130J tactical transport aircraft, 14 NH90 maritime helicopters, 18 Bell 412 helicopters, 16 Sea King helicopters. Norway is modernizing its fleet, particularly by replacing its 60 F-16s with 52 F-35s. Canada: 18 CP-140 Aurora long-range anti-submarine warfare (ASW) aircraft; 80 CF-18 combat aircraft that can be deployed to the Arctic. Denmark: 3 patrol aircraft; plans to acquire 27 F-35. Finland: plans to replace its 62 F/A-18C Hornets with 64 F-35s during 2025-2030. Sweden: at least 100 Gripen fighter jets. In 2023, Norway, Sweden, Finland and Denmark agreed to jointly operate their fighter jet fleets, totaling 250 jets. |

| Air defense and coastal defense | S-300 and S-400 anti-air systems and short-range Pantsir and Tor M2DT surface-to-air systems.

K-300P Bastion-P and 4K51 Rubezh coastal defense systems and medium-range P-800 Oniks anti-ship missiles. |

NORAD maintains air defenses against aircraft and missile threats.

The Nordic countries have a variety of short-range air defense systems, but Sweden is the only one with medium-range defense systems (4 Patriot batteries). Sweden and Finland have RBS 15 missiles for coastal defense. |

| Submarines | Russia has 43 submarines in the Arctic, including ballistic missile (SSBNs), attack (SSNs), guided missile (SSGNs) and diesel submarines (SSKs), many of which are nuclear-powered.

Its Sevorodvinsk- and Oscar II-class submarines can launch both the Tsirkon and the supersonic P-800 Oniks cruise missiles. Eight of its SSBNs have retaliatory nuclear strike capabilities. |

US: a strong fleet of 51 SNN Los Angeles class nuclear submarines capable of operating under Arctic ice.

Norway: 6 Ula class submarines. Sweden has an advanced submarine fleet: 3 Gotland-class submarines and one older model that will be replaced by two new ones in 2027 and 2028. Canada doesn’t have submarines that can operate under ice, but has 4 of its submarines in the Arctic. |

| Ships | The Northern Fleet has 42 ships in total.

These include 10 operational large vessels and the Admiral Kuznetsov aircraft carrier, which is expected to return to service in 2024. Generally, the fleet is old and in poor condition. |

The Arctic is patrolled by the US Coast Guard. Many U.S. aircraft carriers, major combat ships, and amphibious warfare ships can operate there. However, they need the support of icebreakers.

Norway: 10 ships plus support vessels. Canada: 12 Halifax-class patrol frigates. Denmark: 3 large frigates, 2 support ships, and 8 patrol vessels. Sweden: 7 corvettes. |

| Icebreakers | 7 nuclear-powered and 30 diesel-powered icebreakers, which is far more than other nations have.

The fleet relies heavily on civilian nuclear-powered icebreakers. Russia planned to increase its number of heavy-duty icebreakers by 2035, but there have been major funding cuts and delays. |

US: 2 diesel-powered icebreakers.

Canada: 6 large and 7 small unarmed icebreakers. Denmark: 8 patrol vessels that can move through ice. Finland: 9 icebreakers, and 4 under construction. Finland is one of the leading designers of icebreakers. Sweden: 5 ice-breakers |

| Ground equipment | Prior to 2022, Russia had about 50 tanks, 450 armored personnel carriers and an undefined number of other vehicles in the Arctic

|

According to open sources, the US (1, 2, 3), Canada, Sweden (1, 2) planned to modernize their ground forces in Arctic by acquiring over 120 tanks and over 400 armored vehicles in total. |

| Troops | There are a few hundred to a few thousand soldiers per Arctic base.

Most troops under OSK Sever are in the Arctic Brigade, composed of the 80th and 200th Separate Motor-rifle Brigades, and Special Forces units from the 61st Naval Infantry Brigade, as well as the 76th Guards Air Assault Division and the 98th Guards Airborne Division. These brigades took heavy losses and have been substantially weakened while fighting in Ukraine.

|

US: Alaskan Command, Alaska National Guard and the U.S. Marine Corps.

Norway: the Brigade Nord has 4 maneuver battalions and support battalions, two battalions, and the local district of the Norwegian Home Guard. Canada: about 5000 Canadian Rangers, a lightly armed militia supported by 4 Arctic Response Company Groups of the Canadian army. Denmark: the Frømandskorps and Jaeger special forces each contain about 200-300 troops in both Greenland and Denmark, plus a small military patrol force in Greenland. Finland: The Jaeger Brigade consists of two battalion-level units. Sweden: the Norrbotten Regiment, one of Sweden’s largest, has a few hundred troops based near the Arctic. |

Sources: “The Russian Arctic Threat: Consequences of the Ukraine War,” Wall and Wegge, Center for Strategic & International Studies, “Arctic Force Structure,” Boulègue, Chatham House. “Arctic Competition Part Two: Military Buildup and Great Power Competition,” FP Analytics, Foreign Policy. “Dark Arctic,” Gronholt-Pedersen and Fouche, Reuters

Note: NATO doesn’t have a unified command for the Arctic, thus we list forces of relevant NATO countries in the region.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations