The joint effort that liberal democracies have taken to support Ukraine after Russia’s full-scale invasion in early 2022 is commendable. Thirty-two countries have supplied military assistance so far, with some dedicating 0.5-1.0% of their 2022 GDP to help Ukraine defeat the aggressor. Nonetheless, some observers started suggesting that partners are wasting excessive funds on Ukraine’s military support while their own economies suffer from high inflation and sluggish growth. We provide evidence that international aid to Ukraine, while offering it a genuine chance for its victory and thus ensuring peace dividends for the world in the future, imposes on Ukraine’s allies much lower costs than may seem at first sight.

Military Assistance to Ukraine: A Marathon of Partnership

In the face of Russia’s aggressive actions, including the annexation of Crimea and occupation of parts of Donbas, military aid to Ukraine between 2014 and 2021 remained rather modest. Before the start of the full-scale war in 2022, the United States, for example, provided a meager USD 2.5 billion in security assistance to Ukraine (Arabia et al., 2023; Mackinnon and Detsch, 2021). The UK parliamentary report on military assistance to Ukraine in 2014-2021 says that, in addition to extensive training, the Government provided Ukraine with non-lethal military equipment worth only GBP 2.2 million over 2015-2017. After Russia started actively amassing its troops on Ukraine’s border in 2021, the UK and Ukraine signed an Intergovernmental Framework Agreement enhancing joint projects to develop Ukraine’s naval capacities with the provision of GBP 1.7 billion of financing (Mills, 2022).

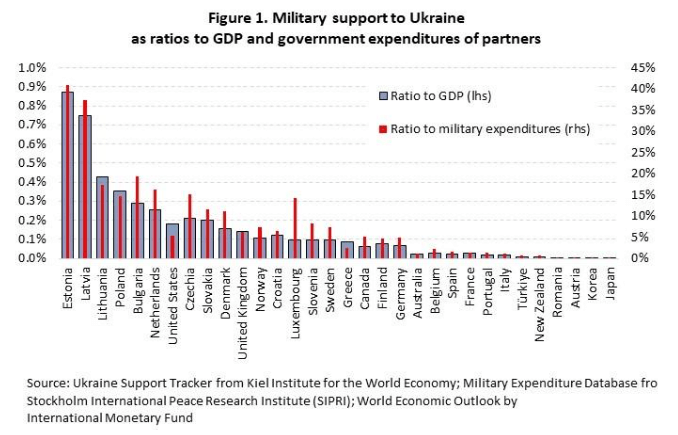

The situation changed dramatically after the full-scale Russian invasion in February 2022, although it still took some time for Ukraine’s partners to accommodate the idea of supporting Ukraine with arms. According to estimates by the Kiel Institute for the World Economy, the total commitments of military aid to Ukraine over 2022 amounted to about USD 66.5 billion*. This includes promised weapons, training, auxiliary services and financing the procurement of military goods. While this figure appears impressive, particularly relative to Ukraine’s economy and past assistance packages, it constitutes only up to 5% of the combined 2022 defense spending of donor countries, according to data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI). At the same time, there is a large disparity in assistance to Ukraine among partners relative to their GDP and defense budgets. Countries that feel the most immediate threat from Russia, especially Latvia and Estonia, have committed a significantly larger portion of their resources towards military support for Ukraine (Figure 1).

* Hereafter authors used data from Kiel Institute for the World Economy that were available at the time of writing. Kiel Institute revises the data as the new information arrives. These revisions do not alter main results of our research.

The cost of Ukraine’s loss in the war would be enormous. Besides millions of lives lost, it would lead to a series of wars in Europe and elsewhere, since Russia’s goal is to restore the Russian Empire in the USSR borders and probably beyond them. Besides, other authoritarian regimes would be encouraged to attack their neighbors with implicit or explicit support from Russia and/or China. In economic terms, this would imply the loss of peace dividend and a jump in poverty levels for decades to come.

Thus, helping Ukraine win as soon as possible is clearly beneficial for the long run security and growth. However, even in the short run, as we show below, military support of Ukraine will stimulate economic growth and thus will be much less costly than one may infer from looking at commitment numbers.

Economic Ripple Effects: Exploring the Fiscal Multipliers of Military Assistance to Ukraine

In the realm of economics, the adage “what goes around comes around” holds true quite literally. When a government spends a dollar, a significant portion of it normally settles within the country, setting the stage for the concept of the fiscal multiplier – the ratio of change in output in response to a government intervention. Expenditures on defense are not isolated from the economy, with some researchers arguing that this type of government expenses may invoke a positive and lasting multiplier (see, for instance, Sheremirov and Spirovska, 2022; Auerbach and Gorodnichenko, 2012; or Gerchet and Will, 2012 for a meta-analysis on fiscal multipliers). Thus, each unit of currency spent within the defense sector has the potential to generate additional economic growth through various channels.

In the forthcoming paper by Chebanova et al. (2023), we quantify the effect of a military-spending shock on output for countries that provided military support to Ukraine in 2022 according to the data of Ukraine Support Tracker by the Kiel Institute for the World Economy. We follow the methodology of Sheremirov and Spirovska (2022) but extend the analysis to capture a recent period of fiscal expansion related to the full-scale war in Ukraine and also a longer period following the first Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2014. We find that a dollar increase in military spending by the donor countries is associated with a 65 cents increase in output within the same year. The largest impact of defense expenses at USD 0.79–0.87 is expected in one to two years ahead, and the cumulative impact is felt even five years into the future.

Some studies have consistently shown that multipliers stemming from investment-related expenses are considerably higher than those associated with consumption-related spending (see, for example, Aschauer (1989) who estimates positive long-run effects of government investment on productivity). While transferring weapons to Ukraine, our allies are renewing their arsenals and expanding military infrastructure. Therefore, we can expect a share of investment in defense expenses to be high. Moreover, numerous studies highlight the existence of larger fiscal multipliers during periods of economic recession, which is seen by many forecasters as the key risk for the global economy in the near future.

Thus, military assistance to Ukraine is not an economic loss to the donor countries. The military expansion in partners’ economies in 2022 is expected to generate growth at least in the nearest five years, which will partially offset their expenses on supporting Ukraine.

Beyond the Numbers: Exploring the Less Tangible Advantages of Bolstering Ukraine’s Defense

There are additional pragmatic reasons for supporting Ukraine with arms and other defense-related goods/services. These second-level effects may be more difficult to quantify but their significance should not be underestimated.

Exchange of military experience. Several high-level military officials from NATO countries highlighted (1, 2) that the Ukrainian army is the most experienced military force at least on the European continent. Ukraine’s partners have scaled up existing or opened new training programs for the Ukrainian army since the start of 2022. For example, the EU Military Assistance Mission launched last November is expected to train up to 15,000 personnel of the Ukrainian Armed Forces over a span of two years. During such programs the knowledge flow is not necessarily one-sided, as allies’ military personnel can also learn from Ukrainian soldiers. This knowledge will certainly add to the security of NATO countries, which in turn will lower their risk premiums.

Better resource allocation in the defense sector based on battlefield arms testing. Notably, the recent successful interception of six supposedly “invincible” Kinzhal missiles by decades-old Patriot anti-missile systems offers the Western coalition valuable information on the effectiveness and limitations of their arsenal. Such insights enable continuous improvements and inform future defense strategies. In particular, the identification of the best-performing weapons among those sent to Ukraine will allow our partners to focus production on the most effective units, as they modernize their armies. This will enable the unification of arsenals and related economies of scale.

Impulse for large arms exporters. The battlefield success of weapons produced by NATO countries and their allies can play a pivotal role in securing new contracts for respective arms companies. With the superiority of their weapons becoming increasingly more evident, the share prices of major arms producers have surged since the start of the full-scale invasion. Between February 18, 2022 and June 12, 2023, the share prices of the largest companies in each donor country for top-20 producers in 2021 according to SIPRI, grew between 19% (Lockheed Martin Corp., USA) and 59% (BAE Systems, UK). For comparison, over the same period the S&P 500 declined by 0.2%, while the UK benchmark FTSE 100 increased by a negligible 0.8%.

The demand for products of these companies will increase not only because Ukraine’s allies are modernizing their arsenals as they transfer not-so-new weapons to Ukraine but also because some countries are likely to switch away from Russian weapons. For example, India in 2018-2021 procured about 44% of its imported arms from Russia (SIPRI data). With some supply commitments Russia made before the full-scale war seriously delayed and potentially even cancelled, India has been actively diversifying its import of arms. In our view, it is more likely to switch to NATO-based companies than to Chinese ones. Indeed, a new Indo-Italian defense cooperation memorandum was signed just a couple of months ago.

Enhanced R&D investment. As The Economist (2023) aptly and somewhat cynically observed, “war ought to be a “battle lab” for new ideas”. The need to upgrade the arsenal is likely to induce additional research and development, which have the potential to contribute to long-term productivity growth – and not only in the defense sector. Thus, Steinwender et al. (2019) show that for OECD countries, to which the majority of Ukraine’s allies belong, a 10% increase in defense R&D results in a 4% increase in private-sector R&D with spillovers between countries.

Many defense R&D projects involve multiple countries. For instance, Storm Shadow missiles, which have proven very effective in the hands of Ukrainian defenders, were the result of cooperation between Britain and France. Earlier this year Japan, the UK, and Italy announced a joint venture to develop a next-generation fighter. As more such projects emerge, democracies will experience stronger technological spillovers across countries and sectors strengthening economic ties and boosting productivity.

Concluding Remarks

After testing the resilience of the existing security framework for years, Russia shattered it completely on February 24th, 2022. At this critical juncture, Ukraine’s partners can no longer afford to ignore changes in the global security landscape. The first invasion of Ukraine by Russia in 2014 failed to generate the necessary momentum to bolster global defense capabilities. Numerous NATO members, including prominent ones like Germany, France and the Netherlands have consistently fallen short of meeting the alliance’s 2% defense spending to GDP minimum target over the last decade. This shared complacency regarding the risks posed by Russia translated into the limited military assistance provided to Ukraine in 2014-2021.

The cost of establishing the new global security architecture stands high. The Economist’s simulations suggest that given Russian invasion and Taiwan-China tensions, global defense spending may surge by USD 200 billion to USD 700 billion (9-32%) a year. However, liberal democracies can lower their future total bill by providing Ukraine with arms and funds in this fateful moment. As noted by Gorodnichenko (2023), the cost of containing Russian forces in Ukraine is significantly lower than what the West would face if Ukraine were to be defeated.

In fact, our analysis shows that the cost of supporting Ukraine is much smaller for the Western economies than the announced amounts due to economic ripple effects and a number of positive externalities. For now, the key partners seem to share this view. Echoing President Zelenskyy’s address to the US parliament, recent Speaker of Congress Nancy Pelosi stressed that supporting Ukraine “isn’t about charity; it’s about security”. Indeed, buttressing Ukraine’s capacities at this crucial moment not only ensures long-term peace on the European continent but is also likely to deter other dictators, particularly those armed with nuclear weapons, from waging brutal wars against their neighbors. The question every democratic government now faces is: What is the present value of long-term security for you?

Disclaimer: The views and opinions are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the National Bank of Ukraine.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations