Mass deportations of peoples in the Soviet Baltic states and other regions in the 1930s–1940s became one of the most horrifying crimes of the Stalinist regime. Hundreds of thousands of people ended up in camps and special settlements, where many died from hunger, disease, and forced labor. The social, political, and national categories of “enemies of the people” were fabricated, and persecution served as a tool of control and intimidation.

After the collapse of the USSR, the Baltic states had the courage to give a legal assessment of Stalin’s crimes. Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania adopted genocide laws that went beyond the 1948 UN Convention, including forced deportations and executions of resistance participants. Under these laws, law enforcement agencies in these countries investigated the activities of veterans of the Ministry of State Security involved in the liquidation of liberation movement participants, deportations, and other crimes of the Soviet regime. In 2003, social and political groups were added alongside ethnic ones as victims of genocide. An important role in the study of Soviet and Nazi crimes was played by the Genocide and Resistance Research Center of Lithuania, which still documents deportations and repressions, preserves archives, and provides materials for academic and legal research.

In 2022, during Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the Baltic ministers called on the EU to establish a Special Tribunal to investigate crimes of aggression. As Latvian MP Ainars Latkovskis noted, after World War II, only the Hitlerites were tried, while the Stalinists remained unpunished. Therefore, today, Russia must be held accountable for its atrocities to prevent future aggression.

Soviet Context and Nuremberg

At Nuremberg, the Soviet side nominally tried to use international law as a weapon — not only to condemn fascism and Nazism but also to prevent their revival. However, in reality, for Moscow, the tribunal was a chance to shift all blame for unleashing the war and crimes against civilians onto Nazi leaders. Therefore, as early as December 1943 in Ukraine, the Soviet authorities organized their own “trial of the aggressors” — they prosecuted a number of Germans, a Russian collaborator, and, in absentia, leaders of the Third Reich, accusing them of a “systematic desire to exterminate the Slavic peoples”.

But could these “defenders of truth” be trusted? Historian Norman M. Naimark rightly notes that the composition of the Soviet delegation in Nuremberg did not inspire confidence. Almost all of its key figures had participated in the infamous Moscow show trials of 1936–1938. One of them was Andrey Vyshinsky, “Stalin’s unrelenting attack dog”, who insulted defendants during trials, disrupted their attempts to defend themselves, and built fabricated accusations.

In 1946, he was Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs of the USSR and headed a secret special commission on Nuremberg affairs that reported directly to Molotov and Stalin. This commission had one task: to ensure that no one mentioned Soviet-German agreements, let alone the cooperation of 1939–1941.

Thus, Soviet participation in Nuremberg was not so much about justice as it was about controlling the truth and concealing its own crimes.

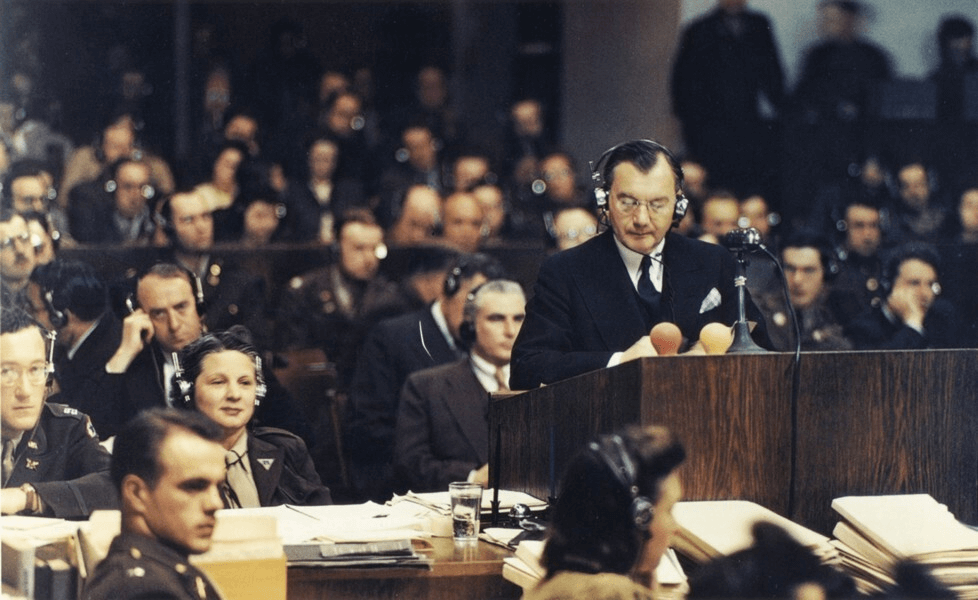

Justice Jackson Delivering the Opening Statement at Nuremberg. Courtesy of the US Army Signal Corps. Katherine Fite Lincoln Papers, Harry S. Truman Library & Museum.

According to Naimark, the Soviet leadership was left disappointed: the trial did not become a triumph of the Soviet system, the defendants were not sentenced equally harshly, and the world paid little attention to the heroism of the Soviet people. This is explained by the fact that in all trials, Nazi war criminals were condemned for crimes against humanity. However, some served only a few years. Others had their sentences reduced or were pardoned for economic or political reasons related to the development of the Cold War.

The disappointment was deepened by the fact that Nuremberg did not adopt a convention against genocide. The Soviet side insisted that the peoples of the USSR, the main victims of Nazism and imperialism, required international protection. At the same time, the delegation was outraged that German lawyers violated the “gentlemen’s agreement” and raised the issue of Soviet crimes, including those made possible by the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact.

However, the USSR still turned Nuremberg into a platform for its own myth-making. The tragedy of Katyn became the centerpiece of this manipulation: responsibility for the shooting of more than 22,000 Polish officers and civil servants was shifted onto the Nazis, even though the executions in 1940 were carried out on the orders of Stalin and Beria by the NKVD. Western judges did not refute this blatant falsification at the time. However, during the trial, Soviet prosecutors failed to present convincing evidence of Nazi guilt. The witnesses and documents they cited did not support the accusations. As a result, in the final verdict of the Nuremberg Trials, the Nazis were not condemned for Katyn. Only in 1990, fifty years after the events, did the Soviet leadership officially recognize the USSR’s responsibility for the execution of Polish officers in Katyn.

This silence became one of the most significant omissions of the Nuremberg process, and simultaneously one of the symbolic victories of Soviet propaganda. In fact, the Soviets managed to create the myth of the “Nazi guilt”, which lasted for decades.

Influence on the UN Convention

In the first drafts of the 1947 UN Convention on Genocide, alongside national, ethnic, racial, and religious groups, there were also social and political groups. Regarding the latter, the United States, China, and other states even proposed clarifying the wording, seeking to expand the list of grounds for protecting societal groups.

But the Soviet Union strongly objected. In its view, “political groups were entirely out of place in a scientific definition of genocide, and their inclusion would weaken the convention and hinder the fight against genocide”. Moscow demanded a focus solely on Nazi crimes and insisted that the text state that genocide is “organically connected with fascism-Nazism and other similar racial theories”.

The Soviet delegation was not the only one that insisted on excluding political and social groups from the genocide convention. As The New York Times wrote, countries such as Argentina, Brazil, Iran, the Dominican Republic, and South Africa feared being accused of genocide during the suppression of internal uprisings. Thus, in this matter, Moscow unexpectedly found itself in the same camp as its right-wing opponents.

However, Soviet proposals went beyond these categories. The USSR insisted on including in the convention the concept of “national-cultural genocide” — the destruction of the language, religion, or culture of entire communities. This concerned not only people but also libraries, museums, schools, and other cultural and religious centers. At the same time, the USSR mentioned only Nazi crimes while remaining silent about its own in the North Caucasus and other regions.

Nevertheless, the United States and its allies rejected the Soviet idea of “national-cultural genocide”, fearing accusations of racism and oppression of indigenous peoples. On the other hand, the USSR got its way regarding political groups: for the sake of compromise, they were excluded from the Convention.

On December 9, 1948, the UN General Assembly unanimously adopted the Convention, which defined genocide as a crime against “national, ethnic, racial, and religious groups”. Political and social groups, however, were left unprotected. This became a loophole that allowed totalitarian regimes to justify their own repressions.

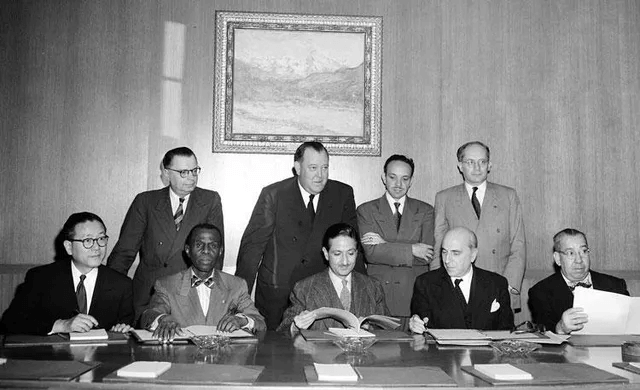

Ratification of the UN Convention on Genocide. Photo: interlaws

This exclusion from the convention made it significantly more difficult for researchers to discuss genocide as a product of the Soviet system. Soviet diplomats argued that such groups were too changeable to be clearly defined.

At the same time, in Stalin’s practice and rhetoric, similar categories were artificially created. The “kulaks”, executed or deported during collectivization, supposedly constituted a separate socio-political group, although in reality, this was an invention of the authorities. Mark Levene, historian and honorary fellow at the University of Southampton, noted that perpetrators often imagine a group as an organized community against its will. This applies both to the kulaks and to the Jews, whom the Nazis selected for extermination.

After the fall of the USSR, the Baltic states regarded Soviet repressions as genocide in a broader sense than in the UN Convention, adding to it deportations and persecution of political and social groups to protect their peoples from past and future crimes.

Baltic Experience

After regaining independence, Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia faced a bitter truth: local communists and NKVD officers had participated in deportations, the liquidation of kulaks, and the suppression of the “forest brothers”. Lithuania began trials for Soviet regime crimes in 1997, and Latvia and Estonia followed in 1998. Since then, Latvia has convicted several former security service employees, and in 2003, sentenced a former KGB agent to five years in prison. The convicted individuals, both Russians and Balts, were part of Stalin’s repressive machine. These trials proved that the ethnic origin of perpetrators does not make their crimes any less genocidal. Thus, genocide can apply to political and social groups even if the 1948 Convention does not mention them.

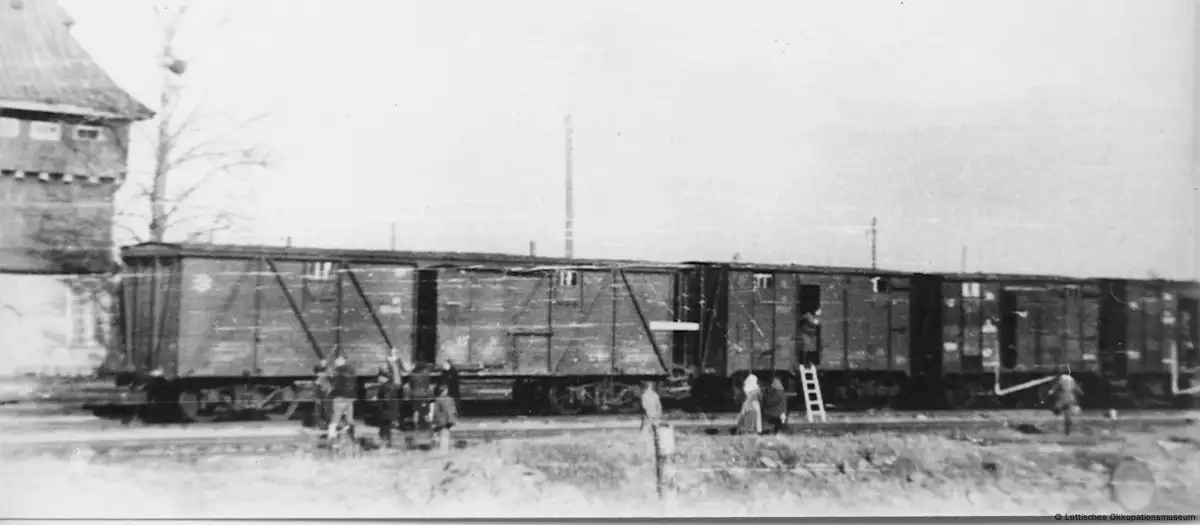

Archival photo of cattle cars used by Soviet authorities to deport people from the Baltic countries (late March 1949). Photo: Lettisches Okkupationsmuseum

The most famous of these trials was that of Arnold Meri, cousin of the first president of Estonia. In 2008, he was tried for the deportation of 251 Estonians to Siberia in 1949. At least 40 people died at that time. Russia traditionally perceived the trial as an attempt by Estonian authorities to persecute World War II veterans and Heroes of the Soviet Union. Meri denied guilt and died before the trial concluded.

The Baltic cases against Soviet genocide organizers revealed another important point: even the destruction of a part of society can be considered genocide if it threatens the existence of the entire nation. Here, the courts referred to Srebrenica: the killing of nearly eight thousand Bosnian Muslims was recognized as genocide because it was an attack on an entire people “as such”. In the same legal context, Stalin’s assaults on the peoples of the USSR in the 1930s and early 1940s can be viewed as attempts to eliminate them “as such”. The Holodomor in Ukraine, as well as the deportations and killings of Poles in the Soviet Union, fully fit this legal logic.

Not only do the Baltic cases confirm that political groups can become victims of genocide. A similar conclusion follows from the trials in Argentina regarding the mass killings of its own population in 1976–1983.

Another lesson comes from Ben Kiernan’s research on Cambodia: social and ethnic motives often intertwine. Genocide is not limited to a single criterion; it has a multidimensional nature, and it is almost impossible to separate the ethnic from the social or political.

A Lesson for the Modern World

The experience of the Baltics and the lessons of Nuremberg remind us that crimes against peoples have no statute of limitations. Today, as Russia wages a full-scale war against Ukraine, amid mass killings of civilians, destruction of cities, and deportations, the experience of the Baltic states becomes especially relevant. It demonstrates that international justice can be an effective mechanism of deterrence and punishment for aggressors.

As in the cases of Stalin or the Nazis, the crimes of modern Russia bear the signs of genocide: they are aimed at threatening the existence of the Ukrainian people “as such”. After all, the Russian Federation still practices the deliberate destruction of identities. Within the federation itself, entire peoples have lost their languages and cultures and have turned into “invisible minorities”. And the example of the Crimean Tatars shows that some nations have been forced to live for decades in exile and alienation. It is precisely this historical impunity that has allowed the Kremlin, in the 21st century, to once again resort to deportations, forced Russification, and colonial policy — now against Ukrainians. Thus, the silence about the crimes of the past creates the ground for the crimes of the present.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations