While all attention is rightfully focused on the human, social and economic damage and destruction caused by the Russian invasion of Ukraine, there are also encouraging signs of resilience and adequate policy making even under such difficult circumstances. Namely, these are continuing functioning of Ukraine’s banking system as well as the domestic currency. The reasons for that are manifold, but prompt and comprehensive anti-crisis emergency regulation by the National Bank (NBU) was probably a key factor. Taking a positive perspective, the well-regulated sector entered this war in a rather good shape, and many similar challenges to the ones ahead, e.g. the emergence of bad loans, have been already tackled successfully after 2014.

Current situation

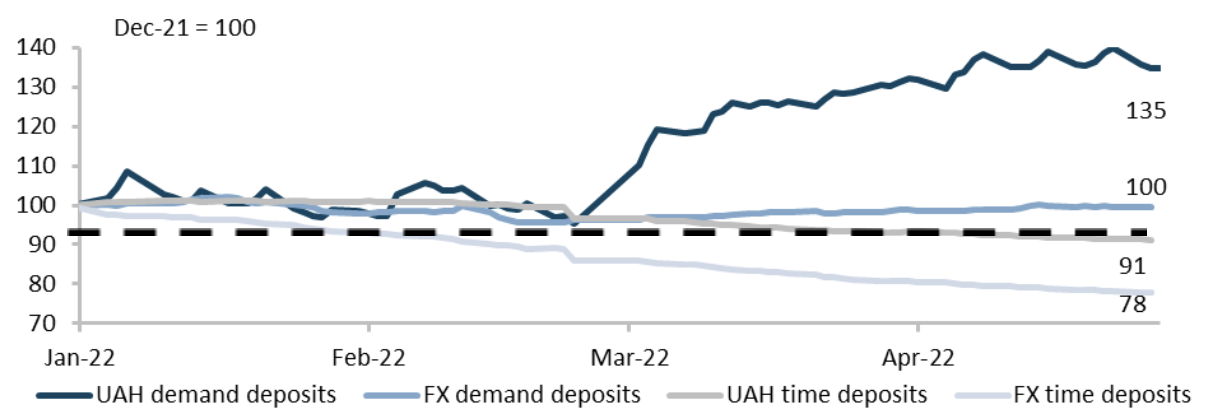

Russia’s invasion has caused an extraordinary pressure on Ukraine’s banking sector stability. Nevertheless, 68 banks continue to operate (two Russian banks were closed in February, and Megabank was closed in June). No major bank-runs on deposits have occurred. However, time retail deposits in FX declined strongly by 22% compared to December 2021 (figure 1).

Figure 1. Development of retail deposits

Source: NBU

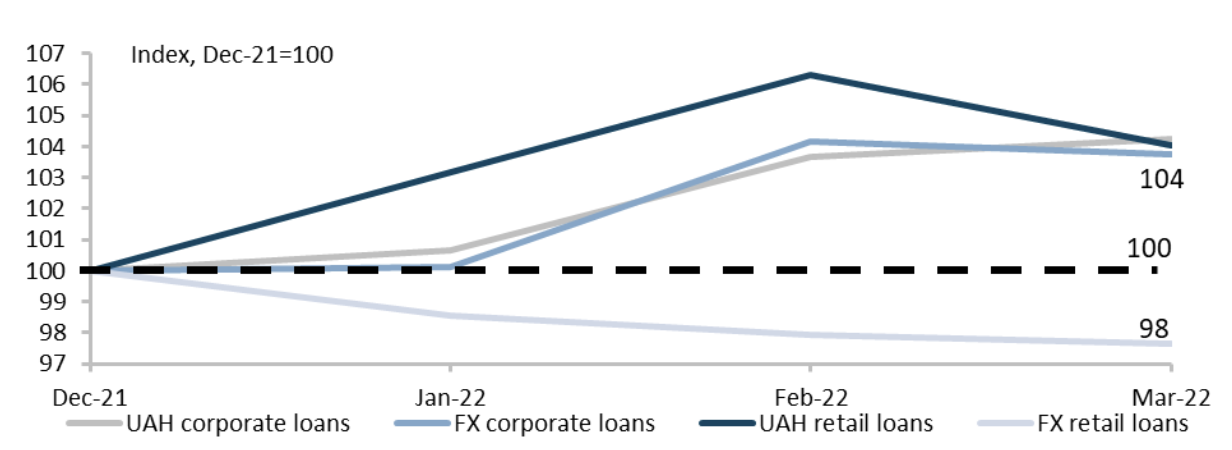

The banks’ net assets have declined by 4% between the year end of 2021 and the end of March 2022 and while both corporate and retail loans in Hryvnia remained relatively stable in March and April 2022. The issuance of FX retail loans has however declined. Currently the new lending is effectively frozen outside of the government-run programs like 5-7-9. With the recent NBU policy rate hike from 10% p.a. to 25% p.a. and corresponding increase in banks’ lending rates, the situation is unlikely to change in the near future.

Figure 2. Development of gross retail and corporate loans

Source: NBU

The sector’s profitability was hit hard as financial losses of UAH 10 bn were recorded in March 2021, driven by a spike in provisions on expected losses. Nevertheless, they remained operationally profitable in March and financial stability has been maintained so far which is an important sign for the sector’s resilience during the first three months of the war.

We see three main reasons as crucial.

Anti-crisis emergency measures

As the full-scale invasion started, the NBU quickly introduced new rules for the banking system and FX market under martial law, including temporary waivers from penalties on violations of capital and liquidity requirements and temporary cash withdrawal limits. Although a fiscal gap of USD 5 bn per month is large, international experts support the monetary budget financing so far, though some discussion is ongoing on its extent (see IMF, 2022; Gorodnichenko and Churiy, 2022). Capital controls on FX transactions are still needed due to FX inflow shortages caused by massive export declines. The policy rate was frozen at the pre-war level until recently, keeping the banks’ refinancing costs low. Overall, the NBU has announced all its measures and subsequent adjustments in a transparent way, which contributes to stability within the sector.

Digitalisation and COVID-related practices

Before Russia’s full-scale invasion, the growing demand for contactless card and NFC payments was fueled by Ukraine’s dynamic IT-sector. NFC technology via Apple Pay, for example, was offered by 62% of banks in Ukraine, similar to Czech Republic (65%), and both contactless card and NFC payments exceeded transactions with physical cards in 2021. The COVID pandemic and remote jobs accelerated the trend. As a result, Ukrainians who were forced to relocate keep operating and receiving payments using digital transactions.

The legacy of previous NBU banking sector reforms

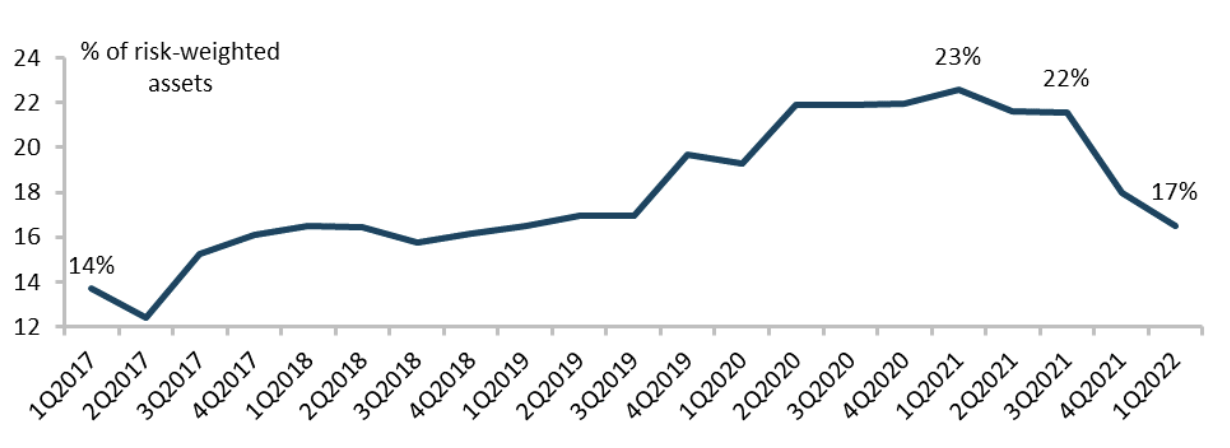

Reforms of corporate governance in Ukraine’s banking sector strengthened the role of supervisory boards as well as improved committee-based decision-making processes. Based on these fundamental steps, a more powerful and independent role of the regulator and a proper assessment of borrowers’ credit quality were established. Further measures included increased capital and liquidity requirements as well as regular stress tests that reduced the number of banks by 50 percent since January 2015 to 71 in December 2021. The remaining banks have individually increased their net assets and experienced rising competition within the sector. Overall, Ukraine’s banking sector is relatively small, but well capitalised. While the sector’s net assets accounted for just 38% of GDP (compared to 97% in Poland) in 2021, the capital adequacy ratio (CAR) was 23% (21% in Poland) in March 2021.

Figure 3. Development of the capital adequacy ratio (CAR)

Source: NBU

Prudent financial and banking policy also contributed to a declining share of FX deposits which opened the room for maneuver in case of sudden FX outflows.

Further challenges to come as delayed shock

Even under a positive scenario of a quick end to this terrible war, there will be several major challenges that Ukraine’s banking system and the regulator will face.

Liquidity situation will likely tighten, given the recent policy rate hike by the NBU. The banks will have to deal with a sudden increase in the cost of funding on refinancing loans (amounting to UAH 145 bn), which will cost them 27% p.a. further on. The banks’ financial performance will likely worsen, as a comparable increase in loan rates on this scale (which could offset the 15 p.p. rate hike) is unlikely – many corporate clients would be forced to go into restructuring. The government is also hesitant to increase the interest rates on its local bonds. So there are not many options left in terms of increasing the profitability for the banks, even though some banks might use the NBU’s deposit certificates to earn the increased interest of 23% p.a.

Therefore, they will likely look for other options on the funding side. Those banks which have no liquidity shortages and a small share of the refinancing loans in their liabilities, will likely rely on their short-term cheap hryvnia resources from the current accounts of individual and corporate clients, while trying to squeeze as much cash flow from the existing loan portfolio as possible. Those with a large share of refinancing loans in their balance sheets will be in trouble and might need to increase the deposit rates much faster to replace the 27% refinancing loans and/or try to secure additional funds from their shareholders.

The deterioration of the asset quality can be realistically evaluated only within 3-6 months after a cessation of hostilities. The NBU will have to gradually return to macroprudential policies aimed at the sector’s resilience. The banks will have to deal with the losses and capitalisation challenges.

There will be a need for extensive, banking system-wide asset quality review similar to the ones performed after 2014 to reveal the true situation. How to resolve NPLs (e.g. recapitalisation of individual banks versus setting up a centralised fund to deal with the expected surge in war-related NPLs) remains to be seen. Injections of fresh capital, which could be delivered by IFIs, could become a form of international support. To improve banking supervision further and as part of Ukraine’s possible path to future EU membership, policy makers should continue to gradually adjust local supervision standards to EU standards.

Promoting new lending will be the next challenge. It should support the post-war recovery but will be impeded by huge security risks associated with Ukraine’s geopolitical position and de-facto limited access to credit. The revival of lending must closely follow the structure of Ukraine’s post-war economy, and in the first stage, the provision of trade finance would be paramount. Risk sharing models between commercial banks, government, and IFIs/donors must be further developed via new instruments (e.g. guarantees and international insurance schemes).

The provision of new lending shall be allocated according to market principles, even though part of the costs may be (initially) paid from the public sector. However, this implies that there must be a continuation of the corporate governance reforms launched before the war, and no roll-back in this area.

Thus, after the war, several challenges for the sector and the regulator will emerge, connected with the exit strategies from the war-time policies like direct lending to the budget and the fixed exchange rate regime. The banks as well as international partners will have to find ways to deal with forthcoming NPL shocks and thus possible new rounds of capitalisation.

References

- Gorodnichenko, Y. and Churiy, O. (2022), “Financial markets in the war and beyond”, VoxUkraine, Link.

- IMF (2022), “Request for purchase under the rapid financing instrument and cancellation of stand-by arrangement – press release, staff report; and statement by the executive director for Ukraine”, Country Report 22/74, Link.

This article has been published in the German Economic Team Ukraine Newsletter Issue No. 163 and is based on the Policy Paper: The banking sector in times of war: current situation and challenges.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations