In February 2022, after Russia’s full-scale invasion, the National Bank of Ukraine (NBU) shifted from a floating to a fixed exchange rate regime. Eighteen months later, as the war’s intensity eased, it returned to a float. Was this state-contingent policy optimal? Or should the NBU have allowed Hryvnia to depreciate to absorb the war shock? A new study shows that while exchange rate flexibility works for small shocks, large shocks — like an invasion — make depreciation suboptimal, justifying the NBU’s choice.

Immediately following Russia’s full-scale invasion on February 24th, 2022, the NBU fixed Hryvnia exchange rate, restricted foreign currency withdrawals and introduced capital controls. In June 2022, the NBU depreciated Hryvnia by a quarter and hiked the key policy interest rate (figure 1). Supported by strengthened reserves, partial macroeconomic stabilization, and commitments under the IMF Extended Fund Facility, the NBU returned to a semi-flexible exchange rate regime at the end of 2023. Capital controls remained largely in place, while NBU interventions continued to slow Hryvnia depreciation and smooth exchange rate fluctuations.

Figure 1. UAH/USD exchange rates and shifts in exchange rate regimes

Source: NBU, www.finance.ua

Fixing the exchange rate marked an abrupt policy shift — Ukraine had pursued a flexible exchange rate and inflation targeting since 2015. Was this the correct move? Or should the NBU have allowed market forces to work?

To explore this, we develop a stylized two-period open-economy new-Keynesian model with frictions in firm price setting (nominal price rigidity) and borrowing on international financial markets. The interaction between these two frictions is the key insight of the model.

The first friction—nominal firm price rigidity—means that not all domestic firms can adjust prices immediately. In the absence of other distortions, this implies that policymakers can insulate the economy from external shocks by prioritizing domestic price stability, even if it requires currency depreciation.

However, like many emerging economies, Ukraine relies on external borrowing, often denominated in U.S. dollars. As a result, large exchange rate fluctuations can destabilize the financial sector. In our model, banks borrow in U.S. dollars on international markets and provide domestic loans in Hryvnia. Therefore, they face currency risks when Hryvnia depreciates. A depreciation increases liabilities and wipes out banks’ capital. Financial frictions work only when shocks are sufficiently large, in which case currency depreciation exacerbates banking sector distress, and banks cannot borrow abroad to finance the desired domestic loans.

The NBU thus faces a trade-off: either fix the exchange rate to avoid a financial crisis, or keep it flexible to pursue domestic price stability and support demand for domestic goods.

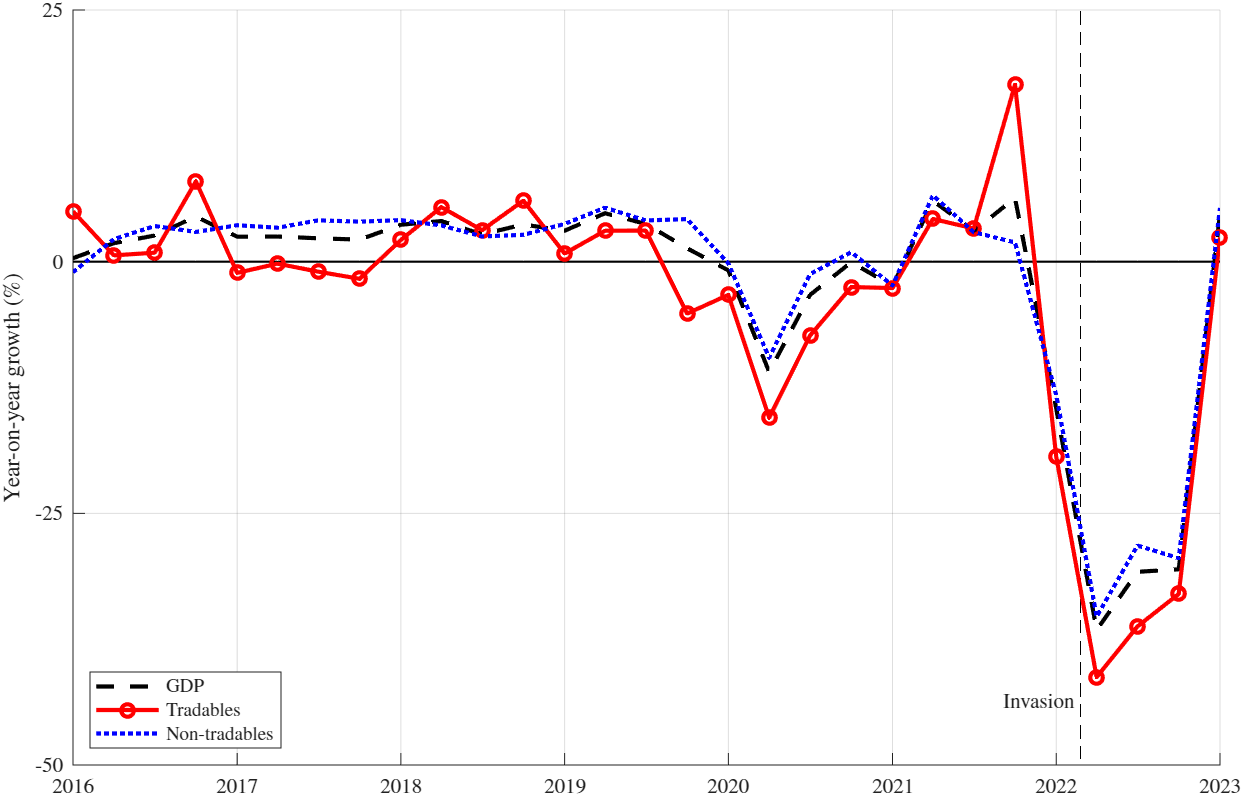

In our model, households earn wages, borrow from banks, and consume both tradable goods (modelled as an exogenous endowment) and non-tradable goods produced by local firms. The NBU uses the exchange rate as the main tool, and the interest rate adjusts in response to the exchange rate decision and the economic situation. We model the war as a negative tradable endowment shock — a drop in imported goods that are not produced domestically. Tradable output in Ukraine contracted by 33% between 2021 and 2022 (Figure 2), which we adopt as the baseline crisis scenario in our analysis.

Figure 2: Collapse in economic activity

Source: State Statistics Service of Ukraine. Note: Tradables is the sum of Agriculture, forestry and fishing; Mining and quarrying; and Manufacturing. Non-tradables is GDP minus tradables; Taxes on products; and Subsidies on products. All in constant 2021 prices.

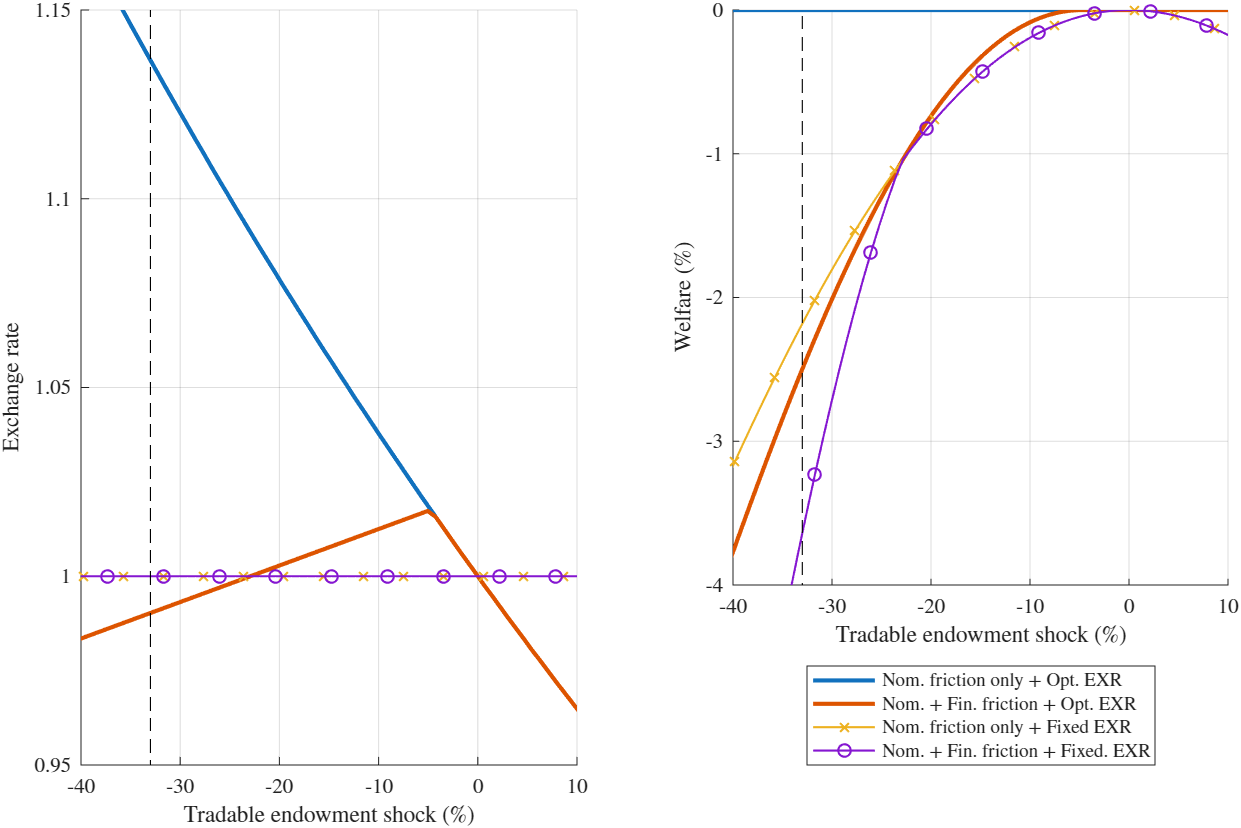

Figure 3 presents the baseline results based on the calibration of the model using Ukrainian data. In each panel, the X-axis is the magnitude of the tradable endowment shock. Zero marks the steady state, and the dashed vertical line at −33% marks the year-over-year fall in tradable output experienced by Ukraine in 2022.

First, we analyze the role of nominal firm price rigidity in isolation, abstracting from the frictions in borrowing on international financial markets. The equilibrium in which the exchange rate is chosen optimally is represented by the solid blue line in Figure 3. The downward-sloping exchange rate curve indicates that the optimal policymaker prefers to depreciate the currency when the tradable endowment falls. This raises the price of tradables in Hryvnia terms, shifting demand toward non-tradables. As a result, firms don’t need to cut prices or reduce output as much. Output and jobs in the non-tradable sector remain stable, helping the economy absorb the shock.

The flat welfare curve illustrates that the “divine coincidence” holds (i.e. the central bank can simultaneously stabilize output and inflation), as the economy attains the same level of welfare as in the efficient equilibrium under the flexible prices.

Figure 3: Response to the tradable endowment shock

Note: Welfare is calculated as the percentage of tradable consumption the household would forgo in the efficient equilibrium (frictionless economy) to be as well-off as in the scenario with frictions and policy response. For example, a −40% change in the tradable endowment under the scenario with both Nominal and Financial frictions and with the Exchange rate set optimally, the household would forgo 2.5% of the efficient level of tradable consumption

The solid red line shows the equilibrium under the optimal determination of the exchange rate in the presence of both nominal firm price rigidity and financial frictions. In response to small negative tradable endowment shocks, the optimal response is to allow the exchange rate to depreciate. However, once the negative shocks exceed a certain size (approximately −5%), the policymaker no longer wants a large depreciation because of its effect on banks. When the shock is −33% (i.e., calibrated to the post-invasion drop in tradable output), the optimal policy actually calls for a modest appreciation (of 2%) rather than a 13% depreciation. Thus, the optimal policy response closely approximates the NBU’s approach of imposing a fixed exchange rate regime.

One extension we consider is introducing a non-zero level of subsistence consumption of tradable goods — the minimum consumption of essentials such as food and energy — that must be met for basic survival, especially during times of war. We calibrate the share of subsistence consumption at 35% of aggregate steady state consumption. This modification amplifies the exchange rate response to endowment shocks within the model. As a result, the policymaker intervenes earlier, halting depreciation at a smaller endowment shock (−3.5%) than in the baseline (approximately −5%).

Hence, we find that the carefully calibrated model can rationalize the NBU’s decision: the optimal response to small shocks is to allow exchange rate flexibility, whereas in response to large shocks—such as an invasion—currency depreciation is suboptimal, and fixing exchange rate is the right policy response.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations