For more than two and a half years, Russia rather successfully pretended that everything was fine with its economy, the situation was under control, and that 25,000 different sanctions had only benefited it. However, in November 2024, several economic indicators simultaneously revealed that Russia’s economy was not as healthy as the official data suggested. This article examines the fundamental problems of the Russian economy and what they might lead to.

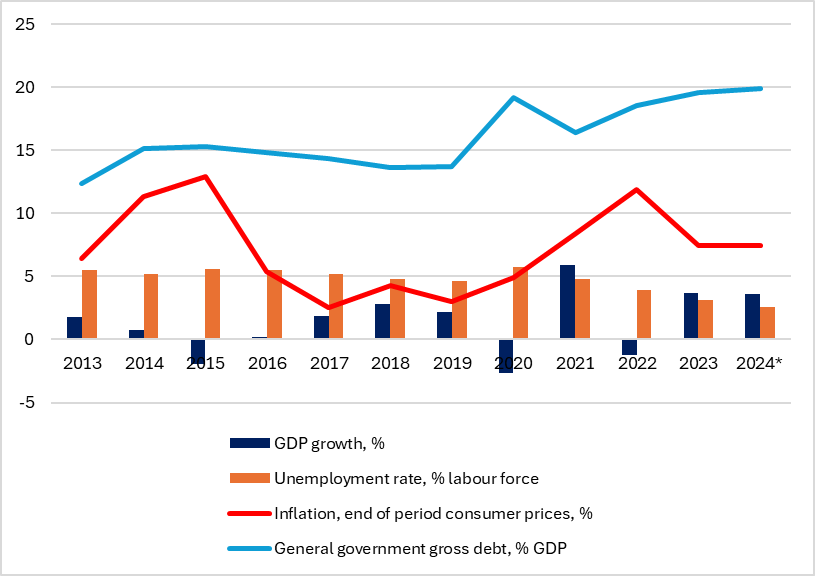

If you look at the official indicators, the Russian economy appears to be doing well (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Selected indicators of the Russian economy

Source: IMF data based on official Russian statistics, *2024 – forecast

But suddenly, in November 2024, the following news appeared:

- On November 27-28, the RUB/USD exchange rate exceeded 115, and the RUB/CNY rate surpassed 15 (the worst levels since March 2022).

- The stock market fell to a 2.5-year low (the worst RTS index value since February 2022).

- The RGBI bond index dropped below 97 (the lowest level in its entire recorded history).

- Inflation went through the ceiling: weekly inflation from November 26 to December 2 reached 0.5%, while monthly inflation for November stood at 1.7%, marking the worst figures since April 2022.

What happened in November? One might think that the U.S. sanctions against Gazprombank announced on November 21 had a significant impact. However, these sanctions will only take effect on December 20, 2024. Therefore, they were likely just a trigger for panic in the stock and currency markets. The fundamental problems in the Russian economy have been developing for years. We discuss them in turn.

Since the Russian economic model is unstable, the collapse of the Russian economy (just like the collapse of the Soviet economy) is only a matter of time, and this time can be shortened with sanctions. Of course, the Russian economy is more resilient than the Soviet one, as it is more integrated into the global economy. For this reason, Western countries are trying to impose sanctions on Russia in such a way as to minimize harm to themselves. Additionally, China, India, and Central Asian countries are helping Russia circumvent sanctions.

However, the war turned out to be an overly expensive “project,” even with relatively weak sanctions and high energy prices (oil and gas revenues account for about one-third of Russia’s budget revenues). So, what awaits the Russian economy? Before answering this question, let’s take a step back and examine the components of Russia’s “economic miracle” in 2022–2024.

What sustained the Russian economy in 2022?

In 2022, Russia experienced a massive influx of dollars and euros due to exceptionally high revenues from energy exports, as prices soared following the full-scale invasion (although Russia started raising gas prices in Europe by limiting supply already in 2021). At the same time, Russian population quickly realized that ruble would depreciate and imports would be restricted due to sanctions, so it was better to invest money in something valuable immediately.

For example, in late February and March 2022, Russians actively purchased cars, household appliances, and apartments. Additionally, Russian entities effectively acquired the assets of Western companies that exited Russia for next to nothing. From the perspective of the real economy, this was merely a transfer from one pocket to another, but statistically, the investment-to-GDP ratio rose from 23% in 2021 to nearly 26% in 2023.

Additional factors that contributed to the resilience of the Russian economy in 2022 included the existence of old contracts (both for the supply of Russian goods and the purchase of imports), which often remained operational despite sanctions. Furthermore, Russian businesses had stockpiles of spare parts and equipment, which could be used while new economic supply chains and sanction-evasion schemes were being established. Budget gap could be covered using the National Wealth Fund (NWF), which accumulated years of savings from hydrocarbon sales.

However, by the end of 2022, it became evident that these factors were running out: sanctions were intensifying, commodity prices had fallen (e.g., natural gas prices in Europe dropped from over EUR 300 to less than EUR 50 per MWh), reserves were depleting (liquid NWF assets shrank by more than 3 trillion rubles or nearly a quarter), old contracts were expiring, new ones were not being signed, and the queue of Western companies exiting Russia was declining.

By the end of 2022, the Russian government even had to “strongly request” that Gazprom contribute over 1 trillion (!) rubles to the budget (4% of that year’s budget revenues).

Thus, after 2022, new “brilliant” ideas were needed to sustain the economy. And the Russian government produced these ideas.

What kept the Russian economy afloat in 2023–2024?

The main idea underpinning the Russian economy in recent years has been a significant shift toward a wartime footing through budgetary spending. This involves channeling a substantial portion of resources into the military-industrial complex, primarily via direct government funding. For example, the 2023 federal budget allocated 4.91 trillion rubles to “national defense,” a 1.5-fold increase compared to the previous year. In 2024, Russia directed nearly 30% of its budget expenditures toward the war effort, compared to 19% in 2023 and 17% in 2022. As a result, government orders for arms manufacturers increased substantially, leading to a sharp rise in industrial production growth rates (3.5% in 2023 compared to 0.7% in 2022). Additionally, revenues for these enterprises and wages for their employees considerably increased.

Another key strategy in 2023 was flooding the economy with loans. The ground for this approach was laid in 2022 when, following the Central Bank’s shock interest rate hike in February 2022 from 9.5% to 20% (to curb potential inflation and stabilize panic from sanctions), the rate was lowered to 8% by the summer of 2022.

Low interest rates, combined with increased incomes of people involved in the war effort, triggered a credit boom in both individual and corporate sectors. This included a surge in private loans (mortgages, consumer loans) and significant borrowing by corporations, primarily enterprises in the military-industrial complex.

For instance, in 2023, the volume of loans issued in Russia grew by more than 1.5 times. Banks approved loans to the population totaling RUB 16.8 trillion (USD 198 billion at the average annual exchange rate of 85 RUB/USD). Nearly half (47%) of all new loans were mortgages: banks issued almost 2 million mortgage loans to Russians totaling RUB 7.85 trillion, 1.6 times more than in 2022 (RUB 4.85 trillion).

In addition, in 2023, nearly 34 million cash loans worth RUB 6.87 trillion were issued to the population, a 45% increase compared to 2022. Auto loans also surged, with volumes growing 2.2 times compared to 2022, reaching a new record of RUB 1.54 trillion (USD 18 billion).

In the short term, both strategies worked—production and consumption increased. However, strategically, these approaches are harmful because they embody the concept of “living today at the expense of tomorrow.” Why?

Risks of increased military spending and credit expansion

Investing money in military production is essentially throwing it into the wind, as the products of military enterprises are quickly consumed (and, unfortunately, used to destroy Ukrainian cities and villages).

Military goods are neither consumer goods (they do not meet population demand) nor investment goods (they cannot be used to produce other goods). Therefore, significant investments in military production benefit only workers of these enterprises, who start to receive higher wages. However, since the production of consumer goods does not increase, these workers can only spend their wages on a limited range of goods, which inevitably leads to higher prices for these goods.

The Russian government has effectively attempted to replace the economic principle of “money-goods-money+” with its own version: “money-goods-money−.” According to the traditional approach, an entrepreneur invests an amount X in production and sells the resulting goods for an amount (X+Y). For the entrepreneur, Y (profit) is the incentive to engage in this activity and a resource to expand the business. In contrast, the Russian model assumes that investing X in production (primarily of weapons) only to have the final goods immediately destroyed (obviously generating no profit), is akin to an economic perpetuum mobile—a self-sustaining cycle of production growth. However, the 2024 increase in defense spending by more than USD 45 billion (67% compared to 2023) shows that this is only overheating the economy with budget funds. Yet, these funds are not infinite: for instance, the liquid assets of the NWF decreased from USD 87 to USD 56 billion in 2023.

On the other hand, a significant increase in loans outstanding is like building a debt pyramid, where older loans are repaid with newer, larger ones. Such a pyramid can be sustained for a while in an environment of low interest rates. However, it collapses catastrophically if interest rates rise. Higher rates increase the number of entities unable to service their loans, leading to bankruptcies of banks and triggering a recession (as was the case during the global financial crisis of 2008).

The significant growth in both private consumption and government spending in 2022–2023 predictably led to rising inflation. To combat inflation, interest rates must be increased, which could trigger a debt crisis and subsequently a banking crisis. By 2024, the Russian government ran out of “creative” ideas, and thus it, as well as the Russian central bank, simply scaled up their 2023 policies. The government increased military spending from 3.9% to 6% of GDP, while the central bank raised the interest rate from 12% in August 2023 to 21% in November 2024, with further hikes expected to 23% or even 25%.

At the same time, the budget ran out of funds for subsidized mortgages, which had been the foundation of the mortgage boom. While the government continues to subsidize already issued loans, it has largely stopped providing for new mortgages.

Scenario for the Russian economy

What can we expect next? The most logical analogy seems to be either the developer crisis in China or the global financial crisis. Without subsidized mortgages, the mortgage lending bubble in Russia will burst. This will lead to bankruptcies of developers, as no budgetary funds are available to bail them out. Signs of this are already visible.

For example, in the third quarter of 2024, new sales by the largest developer, Samolet, dropped by 50% compared to the same period of the previous year. Another top-ten developer, LSR, reported a 47% decline in revenue and an 83% drop in profit for the first half of 2024 compared to the previous year. These financial results occurred before the cancellation of subsidized mortgages when people were still buying real estate under favorable terms.

After the government’s withdrawal from subsidized mortgages, the situation began to deteriorate rapidly. For instance, sales in new residential districts in Moscow and the Moscow region fell by 46% in October compared to the same period last year.

The stock market followed. Four of the ten largest Russian developers are publicly traded companies, with their shares listed on the stock exchange. Over the past year, the stock price of the largest developer, Samolet, dropped by about 80%. The market capitalization of the second-largest company, PIK, fell by more than a half, while shares of LSR (ranked seventh) and Etalon Group (ranked ninth) have declined by approximately 50%.

The decline in profitability or outright bankruptcy of developers will inevitably lead to problems in the banking sector, as it will be a challenge to sell assets backing mortgages. Additionally, rising interest rates increase the likelihood of defaults not only on mortgages but also on other loans (consumer, auto, etc.). For legal entities that obtained loans at 10% rate in 2022, paying the current rates of about 30% will be a significant challenge too. In this scenario, the financial crisis could resemble what happened in 2008–2009.

The financial crisis is highly likely to trigger a payment crisis and, eventually, a systemic economic crisis characterized by a decline in both production and demand for goods. In a “typical” situation (e.g., during the 2008–2009 crisis or the pandemic), governments would soften the blow by injecting money into the economy—refinancing banks, subsidizing households, and even purchasing corporate bonds, and, of course, lowering key interest rates. However, the Russian government has already exhausted the tool of “flooding the economy with money,” and lowering rates would inevitably lead to rising inflation.

Thus, since November, the Russian economy began paying the price for the policies of the past two years. The decline in the ruble exchange rate, stock markets, and bond markets are merely the harbingers of the coming crisis, as speculative capital tends to be the earliest to respond to crises.

What’s next? By the end of the year, the “money rain” will intensify, as in the first 10 months of 2024, RUB 29.9 trillion were spent from the Russian budget (an average of nearly RUB 3 trillion per month), while total budget expenditures for the year are planned at RUB 39.4 trillion (including RUB 2.3 trillion for servicing public debt). This means more than RUB 9.5 trillion (USD 103 billion at the average annual exchange rate of 92 rubles per dollar) will need to be spent in November–December. The central bank will undoubtedly raise interest rates to curb inflation, but this is unlikely to have much effect (e.g., Turkyie’s current central bank rate is 50%, while inflation remains at 47%). However, such a move will accelerate the onset of financial and payment crises.

Additionally, Ukrainian drones and missiles are inflicting losses on Russian production, amounting to hundreds millions of rubles per month. Due to sanctions, these losses cannot be quickly recovered. The damage from a recent operation by the Ukrainian Armed Forces in the Kursk region has already reached nearly RUB 1 trillion (~USD 11 billion). Moreover, further degradation of Russian infrastructure can be expected. Utility networks in Russia are worn out by 40%, and there is neither funding nor a sufficient workforce to implement the necessary repairs. Winter is coming.

Photo: depositphotos.com/ua/

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations