Ukrainian electoral law provides for a clear procedure for errors’ correction in the protocols of precinct election commissions. If the inaccuracy is found in the PEC protocol, then a commission meeting is convened, at which a new protocol with the mark “specified” is adopted. In practice, the correction procedures are often violated. The article looks at the frequency of “specification” of protocols (almost 20%) in the first round of voting in the 2019 presidential election and proposes changes to the procedure that allows avoiding violations of the law.

There has long been a problem of election protocols ‘rewriting’ in the Ukrainian electoral practice. It often happens at the elections night on district election commissions. If you have been following the elections in Ukraine closely for a long time, you will not be surprised by the photos on which the commission members in different poses simply ‘rewrite’ the protocols.

We tried to evaluate the magnitude of this problem using the data from the first round of voting in the 2019 presidential election. We also tried to find out what is the quality of the protocols? What mistakes are made more often while filling in the protocols? Do these mistakes influence on the voting results? What causes these mistakes? How can they be avoided or prevented?

Why is this important?

The election protocol is a summary document that contains information on the voting results. It summarizes the individual expression of the will of citizens in the collective ‘will of the nation’.

Two things are important when drawing up the protocols. The first is that protocols display the contents of ballot boxes. Secondly, to ensure that the rules and procedures are followed when drawing up and submitting protocols. The extent to which these conditions are ensured describes a level of integrity in determining the results of the voting and the election results.

If these conditions are not met, then there are doubts both about the legitimacy of the elections and the legitimacy of the elected authorities. Accordingly, citizens have reasons to ask, on what grounds is the power exercised?

For example, in the US, so-called post-election audits are systematically conducted, one of the aims of which is to check the compliance of the numerals in the protocols with the contents of the ballot boxes. This is practiced to ensure that citizens have confidence in elections and election procedures.

Basics

Each precinct election commission (PEC) must draw up the protocol with the voting results and submit it to the district commission (DEC). The protocol shall be checked and accepted there if it is made without mistakes. If mistakes are found, then the protocol should be ‘specified’. The law requires that the ‘specification’ of the protocol being made at a PEC meeting. To do this, PEC members must return to their polling station, convene a commission meeting, correct the mistake, and draw up a new protocol with a note of ‘specified’. The ‘specified’ protocol is further again transported to the DEC for verification. This procedure shall continue until a correct protocol will be made.

‘Specification’ vs. ‘Rewriting’

The procedure is often ‘optimized’. PEC members ‘rewrite’ protocols directly in DEC premises, which is a serious violation. To do this, they provide themselves previously with protocol blank sheets and also bring the PEC seal, which must remain at the polling station during the protocol handing-over. This, once again, is a serious violation.

Not only Ukrainian researchers of the electoral process but also international observation missions pay attention to this problem. The OSCE mission made censorious remarks in its report, especially about the first round of voting of the 2019 presidential and parliamentary elections. In 49 of the 152 PECs on presidential elections on March 31, changes in PEC protocols were made directly in district electoral commissions. The observation results suggest the systemic nature of this violation.

Electronic ‘prints’ of paper protocols

Electronic messages (EM) are created in district commissions on the basis of PEC paper protocols. After the polling station brings its protocol to the district commission, the data in this protocol is entered into the electronic Information Analytics System ‘Elections’ and so that immediately sent to the CEC (Central Election Commission). Thanks to this information, the CEC can monitor over the process of determining the voting results and inform hereof the people in real-time. Also, this electronic system checks the elective ‘math’, namely – whether the results in the various points of the protocols are aligned.

Results of both primary and all ‘specified’ protocols should be entered into the system. Accordingly, being provided with the information from the primary and ‘specified’ protocols, it can be traced to what changes have occurred. These changes may relate to both the protocols’ figures and the filled-in form. We used ‘electronic’ massages data to evaluate what happened to the original paper protocols in the first round of voting in Ukrainian presidential elections on March 31, 2019.

Not all EMs are equally informative

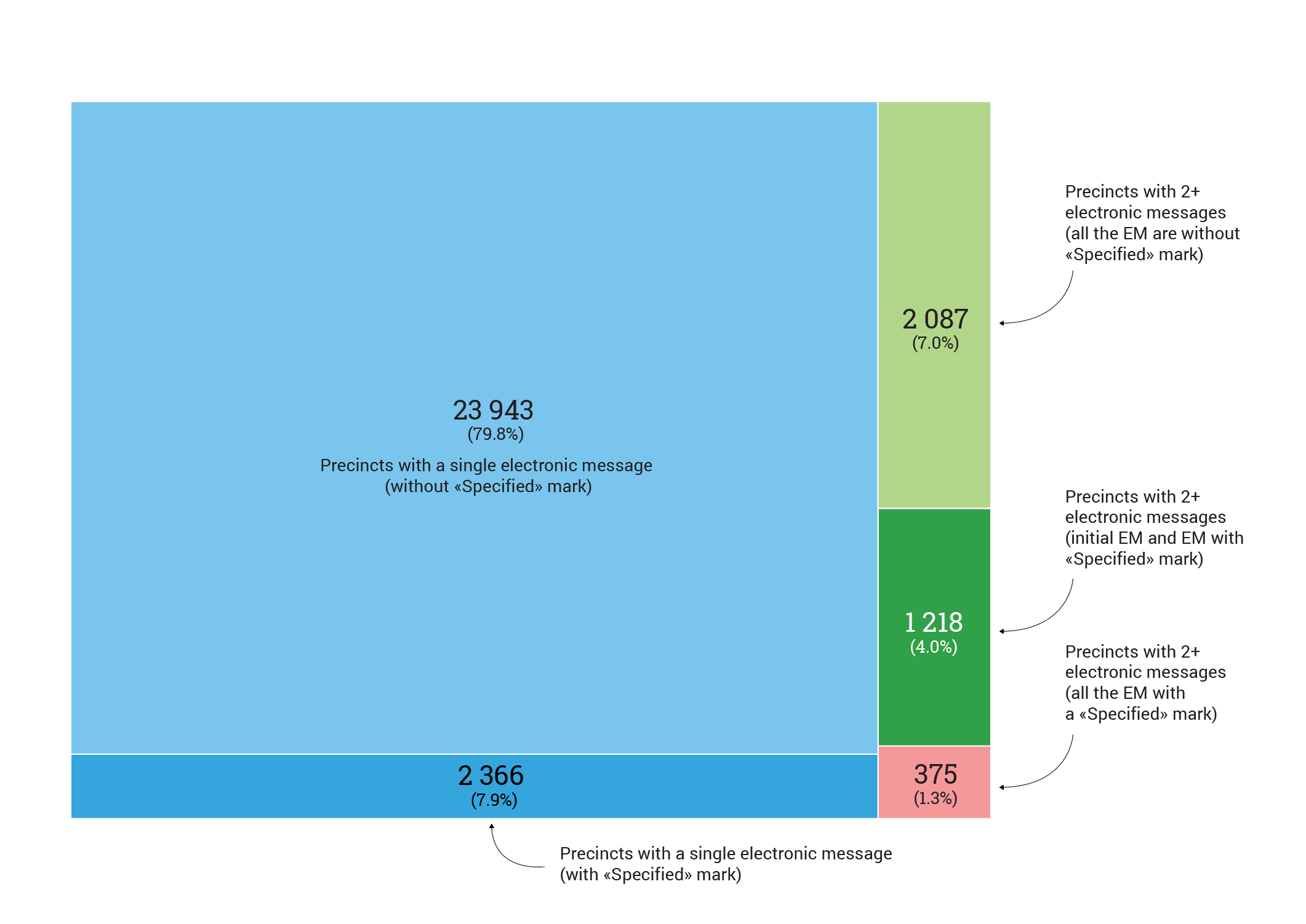

We have systematized and analyzed 34,359 electronic messages entered into the system for 29,989 polling stations. The data attest that 23,943 polling stations, which amounts to 79.8% of their total number, passed election protocols the very first time – one EM was registered into the system for each of these polling stations.

One EM was recorded for 7.9% of the polling stations in the system. However, these messages contain a ‘specified’ mark. This means that protocols were specified at 2,366 stations, but no primary protocols are available in the system. Another 1.3% of polling stations in the system have more than one EM, but all of them are marked as ‘specified’. These two groups of EMs are the most problematic since they do not allow checking the difference of results in the primary and specified protocols. Not too informative, however, these data mean that more than 9% of polling stations were unable to successfully submit protocols the very first time.

More than one EM was entered into the system for 7% of polling stations; however, secondary messages were not marked as ‘specified’. Using EM input time, we determined which ones were entered earlier and which ones were entered later. Accordingly, we interpret the contents of the EM first entered as the content of the primary protocol, and the contents of the most recent – as the content of the latest ‘specified’ protocol. This allows comparing the changes that have been made in the protocol after its ‘specification’.

Both primary and ‘specified’ protocols with appropriate markings were detected for 4% of polling stations. For example, if there were two protocols at the polling station – primary and ‘specified’, then the ‘Elections’ system, respectively, contains two EMs – the primary one and marked as ‘specified’. In general, this particular type of EM can be considered a benchmark, whereas it allows stating about changes between the primary and all subsequent protocols immediately and without prior assumptions.

Hereafter, we checked the differences in numbers between the primary and ‘specified’ EMs from the two latter groups to determine the number of mistakes and to identify their possible causes.

Common mistakes

Most corrections to the EM were made because of mistakes regarding the number of votes for candidates. In total, we found 687 such mistakes at 172 stations.

The commissions at 344 polling stations made a mistake regarding the entering information on the number of protocols that are not subject to consideration. In 243 cases, the commissions, most probably, have mixed up the number of ballots, which were not subject to the consideration with the number of invalid ballots.

Mistakes at 212 polling stations were detected when entering the data on the number of voters in the voter lists at the polling station (at the end of voting). At 120 polling stations, this index, most probably, was confused with the total number of voters who received voting ballots.

Did the ‘specification’ affect the election results?

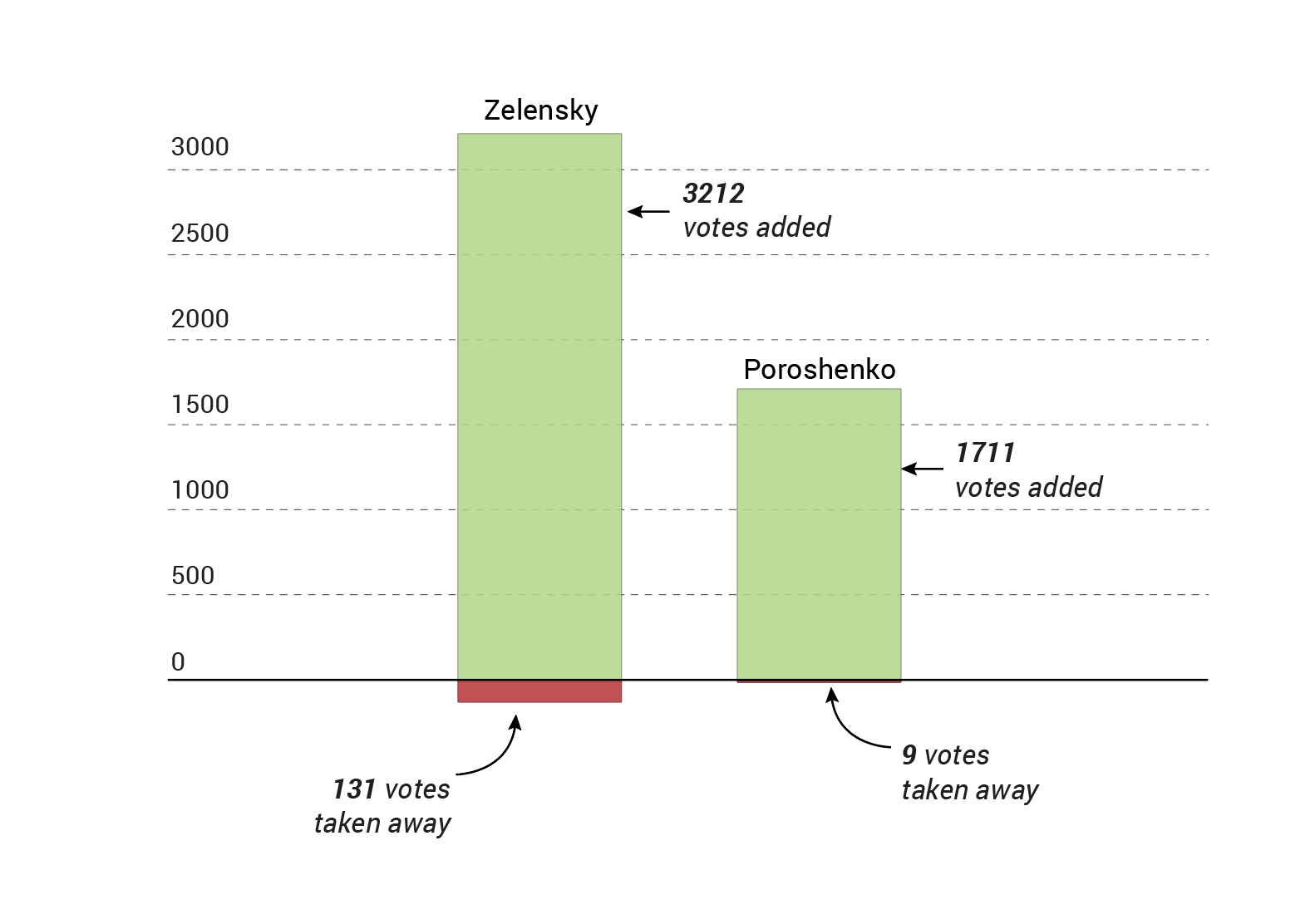

Although most corrections in the EM concerned the number of votes cast for candidates, nevertheless, these corrections did not affect the election results. For example, consider the scope of corrections for candidates Volodymyr Zelenskyi and Petro Poroshenko, who received the most votes in the first round.

Zelenskyi in the first round at 5 polling stations ‘got’ 131 votes more, and at the same time, 3,212 votes ‘have not been added’ at 35 polling stations. That means that after ‘specification’ the total number of votes for Zelenskyi increased by 3,081 (3,212 – 131 = 3,081). Poroshenko during the counting at 2 polling stations was given 9 votes more and at 22 polling stations, 1,711 votes ‘have not been added’ to him. Accordingly, after ‘specification’ the number of votes for Poroshenko increased by 1,702 (1,711 – 9 = 1,702). Considering the difference in support of Zelenskyi and Poroshenko after the first round of voting, the aforementioned difference in votes after the ‘specification’ could not affect the final result.

What the EM is silent about

EMs allow assessing changes in protocols prior to and after ‘specification’. However, there are two things to keep in mind.

Firstly, the EM discloses nothing as to the intentionality or inadvertency of protocols’ mistakes. Simply put, we do not know how the mistakes arise – either through deliberate fraud or because of commission members’ heedlessness.

Secondly, the reasons for the ‘specification’ maybe not only mistakes in numbers. Experience has proven that protocols can be ‘specified’ due to the lack of election commissions members’ signatures, grammar mistakes during filling in, poor seal imprint on the protocol, inappropriate number of PEC members when handing-over the protocols, etc. The reasons may be different. Taking this into consideration, if the ‘math’ in the EM is the same, it is impossible to determine the reason for the ‘specification’ of the protocol. We found 2,454 polling stations for which it is impossible to identify the reasons for the ‘specification’ of the protocols under the EM. In order to do that, it is necessary to analyze the primary and ‘specified’ protocols, which are stored in the Central State Archive of the regulation and administration of superior authorities of Ukraine.

Does the Electoral Code resolve protocols’ problems?

The Electoral Code came into force on January 1, 2020. Although some consider this decision to be historical, the Code does not resolve protocols’ problems. The part of the document concerning the parliamentary elections contains the mechanisms of drawing up, specifying and handing over the protocols from the previous electoral law.

It is worth noting that the version of the Code as of July 2019 allowed, under specific conditions, to amend the protocols by the district commission without returning to the polling station. But this rule has disappeared from the final version of the Code. To hope that maintaining this rule would solve all the problems associated with the protocols would, of course, be naive. However, this could quicken the procedure for accepting protocols in which minor mistakes or inaccuracies were revealed.

It is also worth remembering that the Electoral Code has introduced a new electoral system. This system not only complicates the process of votes counting, but it also provides for a new, more complex protocol form sheet.

What is to be done?

Two problems need to be solved – the poor quality of protocols filling in and, as a consequence, the massive ‘rewriting’ of protocols with violation of the procedure.

It is possible to improve the quality of protocols by raising the qualification of polling election commissions members.

On the one hand, it is a ‘homework’ for the candidates and political parties responsible for mobilization of the polling commissioners. They should involve experienced and trained administrators in the election process.

On the other hand, partial responsibility for the quality of PEC members’ training lies on the Central Election Commission, which organizes training for PEC members before each election. Approaches to the organization of these training should be reviewed in terms of completing the protocols and their specifications. It is also worthwhile to make the protocol form sheet clearer, since, as the analysis has shown, commissions are confusing protocol’s items, which leads to making mistakes.

There are several ways to prevent the unlawful ‘specification’ of protocols. An ‘electronic protocol’ can be implemented as in Poland. Then, if the protocol is rejected, you can only generate a new copy at the polling station equipment. Accordingly, it would be technically impossible to ‘rewrite’ the protocol on knees at DEC.

We can refer to the experience of Georgia, which abolished the protocol specification procedure as such. There, after the election results are established at the polling station, all PEC members are obliged to sign the protocol. Then, after the document leaves the polling station, it is no longer returned, and all comments and changes are reviewed and made at the DEC level.

There is also experience in countries such as Albania, the United Kingdom, Malta, Switzerland, Sweden, in which the vote counting and thus the documentation of voting results take place outside the polling stations. These procedures are carried out in special account centers and, thus, eliminate the need to return protocols to the station.

The aforementioned ways of resolving quality problems and ‘rewriting’ the protocols are not exhaustive and must be perceived as more likely a framework within which potential solutions to these problems may lie.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations