Volatility of capital flows is a big challenge especially for transition economies that don’t have very well developed financial architecture. What are the priorities for capital account liberalization in Ukraine and how the experience of other countries can be used for that – this, among other topics, was the focus of the NBU conference, held in Kyiv on May 19-20.

Zdenek Tuma, KPMG, moderator of the conference:

Moris Obstfeld has shown in his lecture that FDI flows are stable. But they are stable in global terms, for each particular nation FDI is volatile. FDI volatility and generally volatility of capital flows is a big challenge especially for transition economies which have not very well developed financial architecture. EM countries face several challenges – when to open [their borders for capital flows], when to liberalize, when to switch to floating exchange rate regime etc.

These issues we are to discuss at this policy panel.

Oleg Churiy, NBU. Capital account liberalization: experience of Ukraine.

I’d like to start with the history. A few decades ago capital controls were considered an anachronism, and free movement of capital was seen as a solution for capital-constrained countries. But after 2008 crisis the IMF reconsidered its long-held position of recommending free capital flows. Now it recognizes that capital flow management can be used to stabilize the economy.

Ukraine is now moving in a bit different direction than other countries [we are liberalizing when other countries are introducing capital controls].

A couple of years ago we introduced very tight restrictions – not only on capital movement but also on current account operations, on operation of commercial banks etc.

I must stress that capital flow management can’t be a substitute for economic reforms, and we only used it to buy time to implement reforms. During the last 1.5 years we introduced flexible exchange rate, cleaned the banking system, imposed more efficient prudential regulation, got rid of fiscal dominance, eliminated Naftogas quasi-fiscal deficit.

When introducing the restrictive measures, we already started thinking about their elimination, and we developed a comprehensive roadmap for capital liberalization. This liberalization plan is not time-based but condition-based. We think that sudden removal of restrictions can destabilize the market, so we are very cautious in this.

Priorities (stages) for capital account liberalization are a follows:

- Promotion of economic growth – so first we’d like to liberalize FDI and current account;

- Development of financial market. We would like to provide the market with more liquidity so that CB can stop its market-making role (one of ideas currently discussed is introduction of a market-making institution);

- Investment and funding – first of all equity but also debt funding. We would like both to attract foreign portfolio investment and to allow Ukrainian residents to invest abroad. But this is the last stage of capital liberalization.

International experience of capital liberalization is very diverse. For example, Cyprus removed capital restrictions one year after their introduction, while Iceland introduced capital restrictions after the 2008 crisis and completely relaxed them only recently.

Relaxation of capital controls depends on macroeconomic conditions. Conditions in Ukraine have very much improved – currently we have single-digit inflation, GDP growth for a couple of consecutive months; reserves increased considerably and now can cover about 3.5 months of imports compared to one month of imports at the beginning of 2015.

At the same time, many risks are still there. These risks are: very vulnerable external position of Ukraine since about 80% of our exports are commodity-linked and so dependent on international commodity prices. A large share of Ukrainian government debt is owned by the NBU. And of course the war is the very important risk factor (there is always a risk of escalation).

The process of relaxation of capital constraints is iterative – we lift some restriction, see how it works, and then introduce the next step.

Conclusion: restrictions introduced in Ukraine and their liberalization can be used as an example only for countries in very extreme situations. Last year we had a collapse of GDP, a collapse of trade, we had a war, we had bank runs – all at once. And we think the restrictions we imposed and the process of their liberalization were very adequate to the situation which we had and have now. Even if we transfer to a more liberal model, it will not mean that we will not be able to introduce some capital restrictions. Rather, these capital restriction measures can be introduced as a macroprudential regulation. The problem with Ukraine is that introduction of restrictions can be viewed as a very bad signal – even if they are introduced to limit some disruptive trends.

Other lectures at the NBU Conference

Price Selection, Inflation Dynamics, and Sticky-price Models, lecture by Oleksiy Kryvtsov

Taylor Rules versus Discretion in U.S. Monetary Policy. A Lesson for Ukraine, lecture by Alex Nikolsko-Rzhevskyy

Prudential Regulation: Are Government Bonds Safe, lecture by Igor Livshits

Andrew Levin, Dartmouth Colleg

Full presentation can be found here

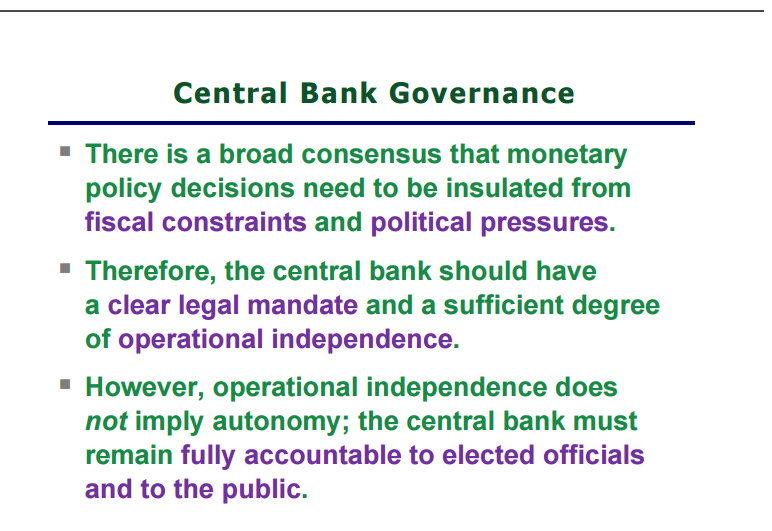

Let me start with a couple of aspects of CB governance and transparency.

First, it is very important for a CB to be insulated from fiscal constraints and from short-term political pressure. Sometimes it is called “CB independence” but I prefer to use a more precise term “operational independence”.

Think of public as an employer, and CB is an employee. A good employer does not monitor an employee very closely – he/she assigns him the task and provides operational independence. CB needs a clear legal mandate – just like an employer has to provide an employee with clear job description. At the same time, the central bank has to be accountable to elected officials and to the public, i.e. clearly and regularly report what it is doing, especially on the key strategic decisions. It is really important to maintain the confidence of the public in the Central Bank, so CB has to clearly communicate its mission and justification for its decisions.

The next thing closely related to communication is the need for CB to be systematic and transparent in monetary policy decisions. We know from many years of theoretical and empirical research that monetary policy is the most effective when it is systematic and well-understood by financial markets and general public. The more systematic and transparent monetary policy is – the stronger is the mechanism of monetary transmission, hence, the less uncertainty there is for the public (and uncertainty undermines growth).

There are three principles of CB operation that remarkably well apply to many (almost all) countries – no matter developed, EM or developing.

- CB does have a paramount task – to preserve the unit of account. When inflation is high – this unit of account is very noisy and unreliable, and it’s hard for economy to grow and prosper. And there is no other agency that can preserve price stability. Hence, the paramount task for a CB becomes price stability, which means anchoring inflation expectations.

To do this, CB has to have a crystal clear goal of medium-term inflation (the inflation target). This target should be very well understood by businesses and public, and the public should see the CB consistently targeting that goal.

To me, 5% within 2-3 years perspective seems a perfect target for Ukraine.

- CB should only rarely intervene in FX market. There are times when intervention is appropriate because it can mitigate transitory exchange rate fluctuations – but it needs to be transparent and systematic.

- Macroprudential tools are crucial for protecting financial stability and ensuring that monetary policy supports price stability.

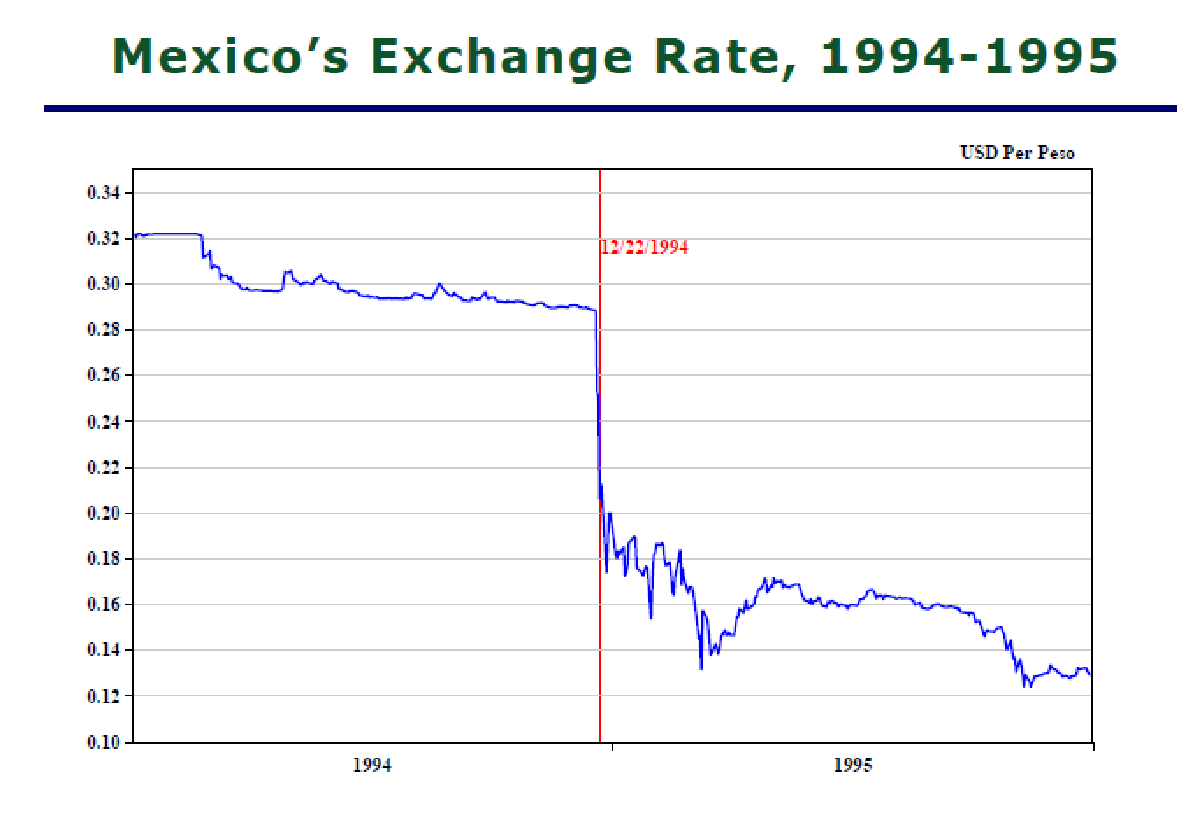

Mexico example. About twenty years ago Mexico had rather distinct political situation. It had only one party which consistently won all elections, so it was like a dictatorship. And in 1994, before the elections, a candidate for the presidency was assassinated. This was a terrible event for Mexico – comparable to assassination of Duke Ferdinand before the WWI. There was no one second in line for the presidency, so it created a lot of political instability and uncertainty. At that time Mexican CB had a crawling peg but in the situation of large uncertainty Mexican CB could not keep it. The CB of Mexico raised its interest rate and tried to support the crawling peg but over the course of the year it nearly drained its reserves. At some point it even stopped publishing its reserves data because if the public learned how bad things were, that would actually exacerbate the problem. However, by the end of 1994 they had to abandon the peg because the reserves almost disappeared (reserves fell from 28 to 3 billion in a year Dec.93-Dec.94).

Exchange rate fell abruptly causing the economic crisis.

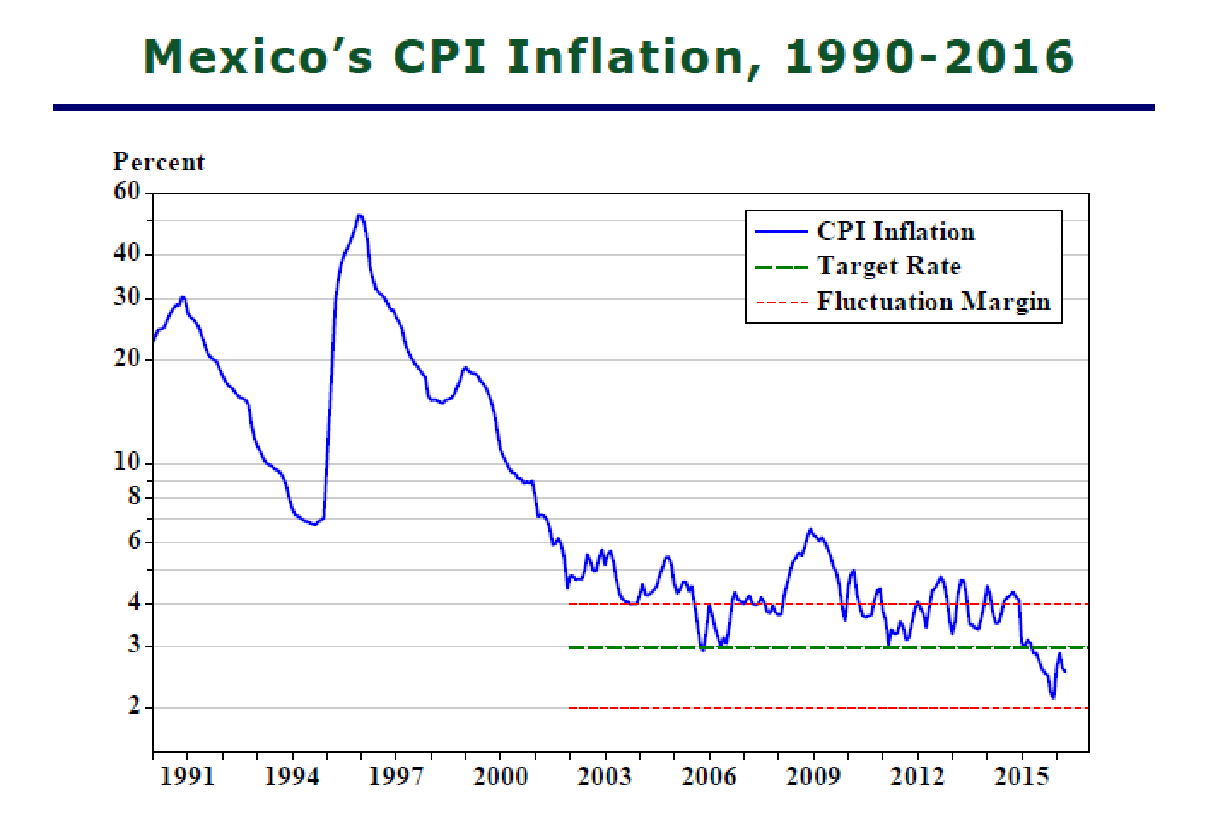

Good news for Mexico were that this provided an incentive to move to inflation targeting, which was introduced in 1996. Mexico was a pioneer in this sense among the EM countries. Since 2002 Mexico has had a single-digit inflation and target 3%-+1% has been mostly met. Mexican CB had a floating exchange rate regime, and it employed some FX interventions only during the 2008 crisis.

Lately inflation has been lower than 3%, which is a bit of concern. I think for Mexico having an inflation target of 3% is a good thing because they are not on the verge of deflation, which could cause an economic slowdown. And for a country like Ukraine having a bit higher target seems very sensitive to me.

Conclusions. CBs have to educate and inform the public about monetary policies and decision-making, not just experts or market participants. This will help build the confidence and also protect the CB from political interference. CB should identify key risks, and contingency plans for addressing these risks should be the key part of the communication. Finally, macroprudential tools play a very important role.

Marek Dabrowskiy, CAS

Full presentation can be found here

Free capital movement was a hot debate in 1990s and early 2000s but today I would argue that we are past this debate, and capital movement is de-facto free. Whether we like it or not, now we must live with free capital movement. It is difficult to reintroduce de-facto capital controls, although de jure they may exist.

In particularly, I cannot imagine effective capital controls in Ukraine when the largest business groups have their mother/daughter structures offshore and freely transfer capital there. I think, the idea that we can effectively manage these flows is very problematic.

In practice capital account or even current account restrictions mostly hit small business and population.

So rather than discussing capital controls, we should discuss consequences of unrestricted capital movement. I will concentrate on two: consequences for balance of payments management and for monetary policy.

Traditionally, BoP management concentrate on current account, and the biggest problem was how to finance current account deficit.

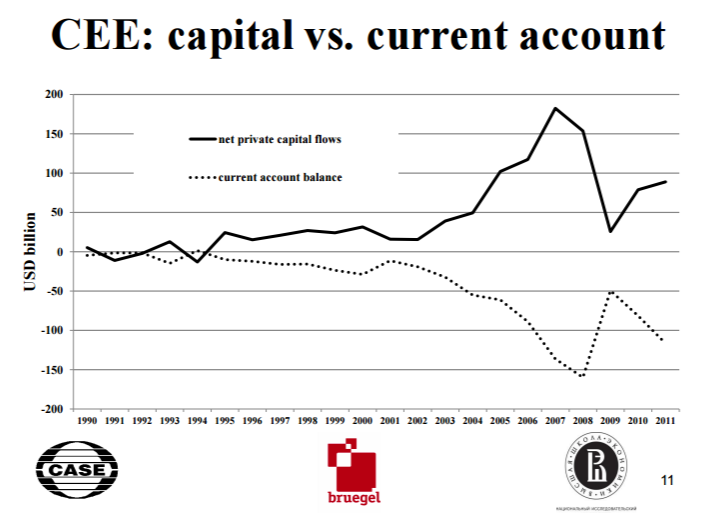

If governments could not finance it, they usually turned to some international institution, such as IMF, for help. However, now we have very different situation. The last financial crisis was mostly driven by capital accounts – in 2008-2009 problems started with an abrupt stop in capital flows. So even countries with good domestic macroeconomic fundamentals had to rapidly adjust current accounts to capital accounts – with all the consequences for domestic employment, output growth etc, and of course the exchange rate. The latest currency crises in former Soviet Union countries were also driven by capital accounts. For example, Russia never had a current account deficit but large capital outflows in 2008-2009 and 2014-2016 caused a currency crisis there. A similar situation is observed in Azerbaijan.

Do we have instruments to control capital flows? I would say that we have some but very limited (e.g. macroprudential regulation). For example, countries which have sovereign funds partly sterilized the impact with their help.

Capital mobility and monetary policy: small countries are often forced to follow large countries, their monetary policy independence is limited – and this is a serious problem (of course it differs depending on the size of economy, its sophistication, diversification and health of financial markets etc). But if there are sharp changes in exchange rate, even under flexible exchange rate regime this creates several undesired side effects in terms of financial sector stability, competitiveness of real economy etc. And it also affects (especially in case of a sharp depreciation) the attitude to domestic currency of domestic currency holders. In emerging market economies this is quite a serious problem which may cause currency substitution. Currency substitution exists even in closed economies – e.g. think about the Soviet Union.

Financial globalization increased opportunities for currency substitution. Of course we can restrict currency substitution with various administrative measures. But administrative measures cannot stop the most risky phenomenon – spontaneous dollarization, which is caused usually by various past experiences – currency crises, political instability, lack of trust to government etc. (i.e. psychological effects are very important). Government credibility is lost very easily and it is not easy to regain. Sometimes this may take decades. People who experienced economic shocks in the past have a long-lasting memory of those shocks, and therefore their reaction to current shocks (panic) exacerbates the effect of shocks.

This to some extent explains the phenomenon of “fear of floating” observed in FSU countries. That is why introducing flexible exchange rates in FSU countries takes so much time.

I don’t question the fact that exchange rate flexibility has a number of advantages. But we must be aware that it has its limits, especially if we are dealing with economies that have these historical fragilities.

Linda Tesar, Michigan Universit

Full presentation can be found here

When I started to look at integration of financial markets as a graduate student, these were the times of the “Washington consensus” – that there will be many benefits of financial markets globalization. We all know what they are, we’ve read about them in the textbooks.

So I’m going to talk about the reality check that we’ve all had – what globalization and global capital flows have and have not delivered and what lessons we’ve learned from that process.

The essence of the “Washington consensus” (early 1990s) is “introduce reforms to get prices right, and things will be efficient”. However, since then we have seen large capital flows followed by a sequence of financial crises. Hence, we had to revise the “Washington consensus” in the mid-2000s, and now we know that markets are not enough, we need “to get institutions right”, and we recognize a central role of government policy in regulation of capital flows.

We hoped that capital markets integration would redistribute capital from capital-rich to capital-poor countries, reduce the cost of capital and help countries to smooth consumption (i.e. in times of adverse shocks countries could borrow at international markets to mitigate a fall in domestic income). All of this would foster global economic growth. What have we seen in reality?

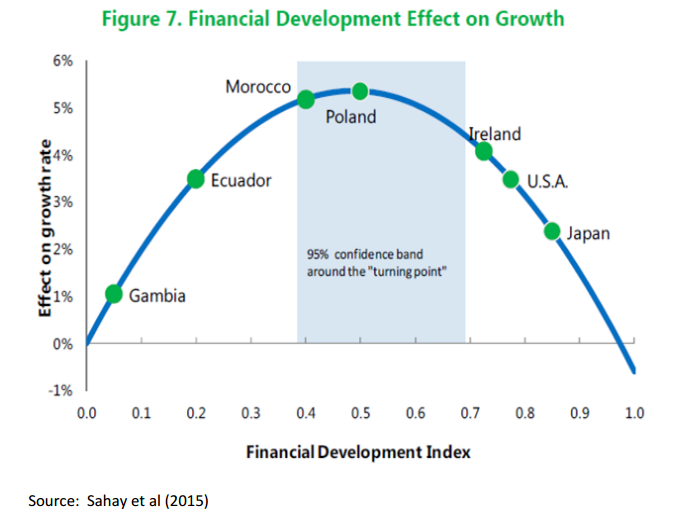

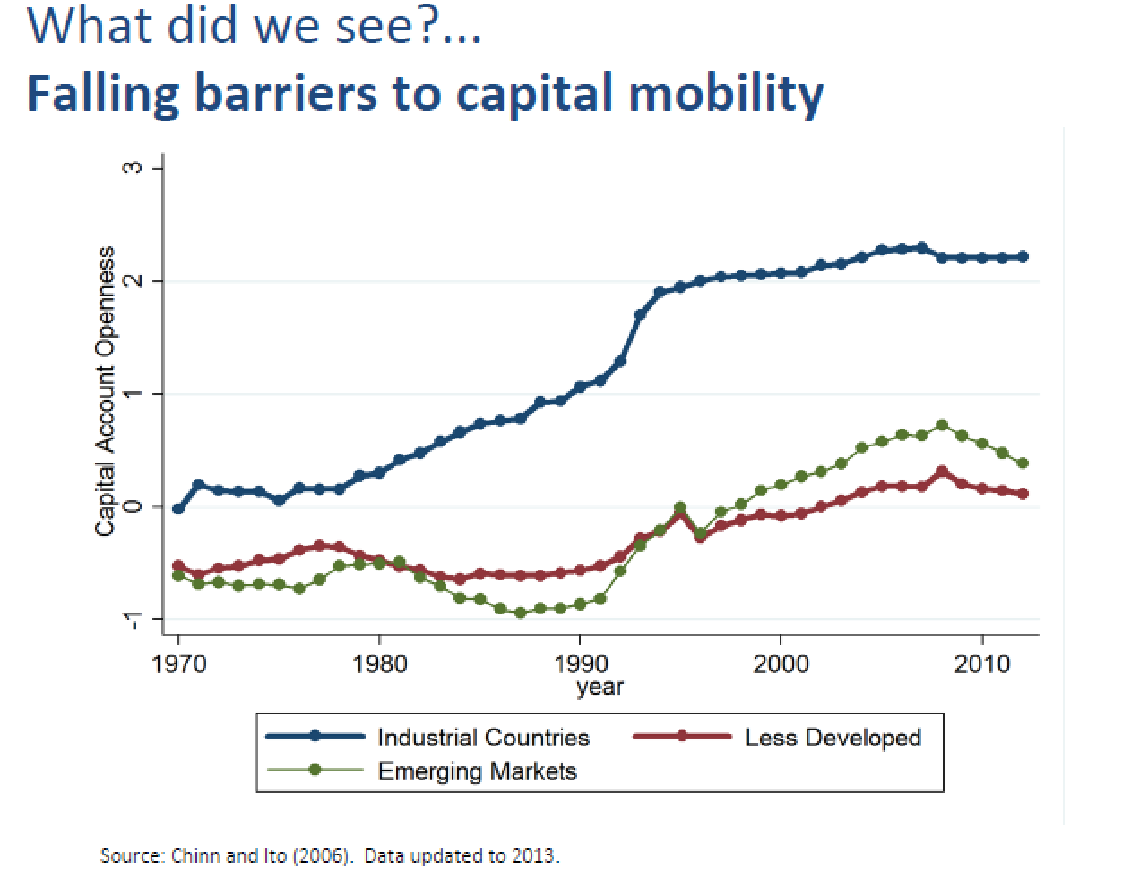

Within the last several decades, there have been a fall in barriers to capital mobility (this figure shows a rise in index of capital mobility).

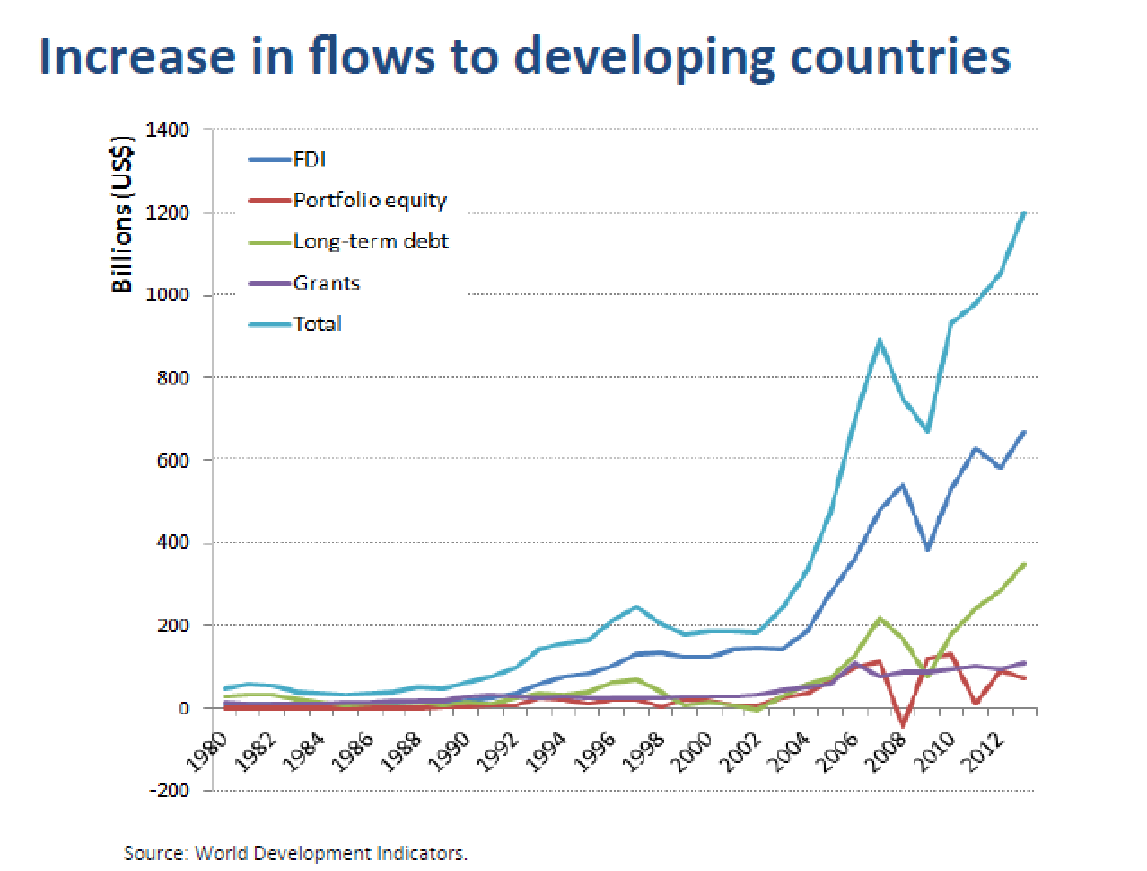

We’ve also seen a rapid increase in capital flows (great rise by 2005), particularly portfolio and debt flows – and a lot of that went to developing countries.

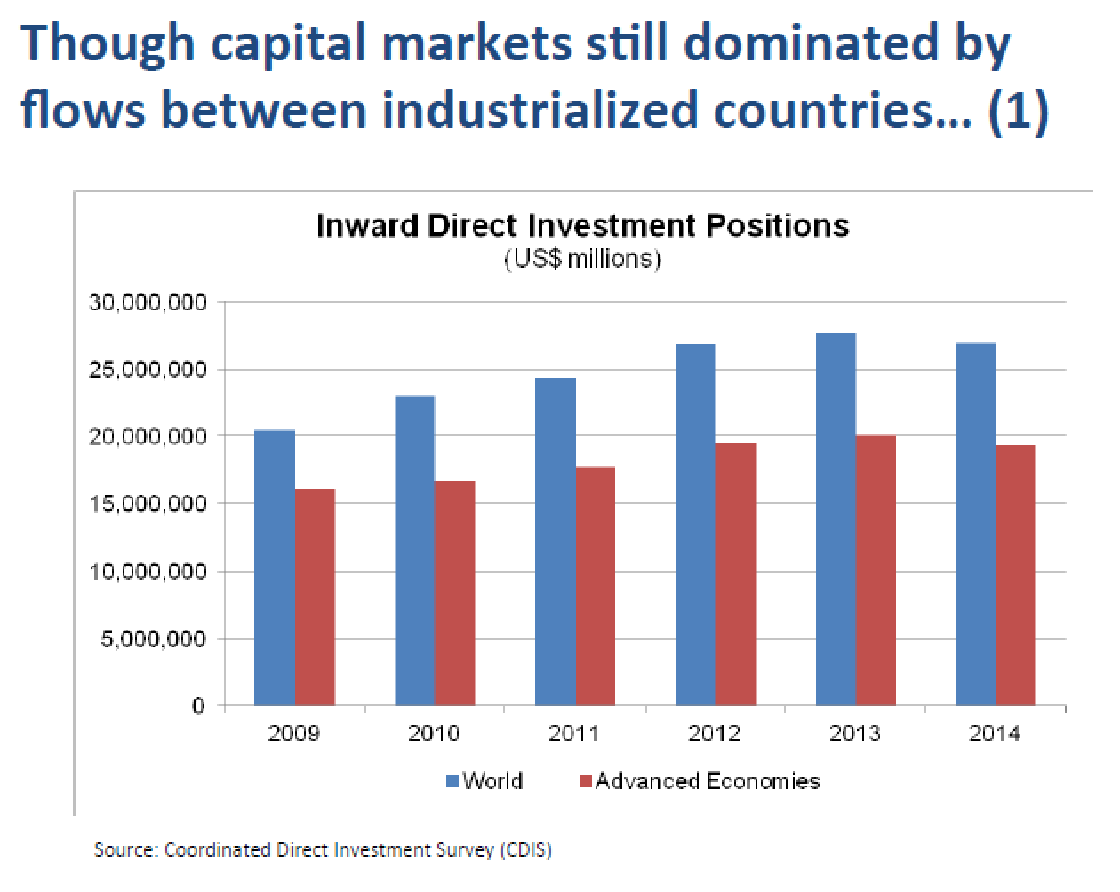

However, investment flows have been predominantly among advanced countries.

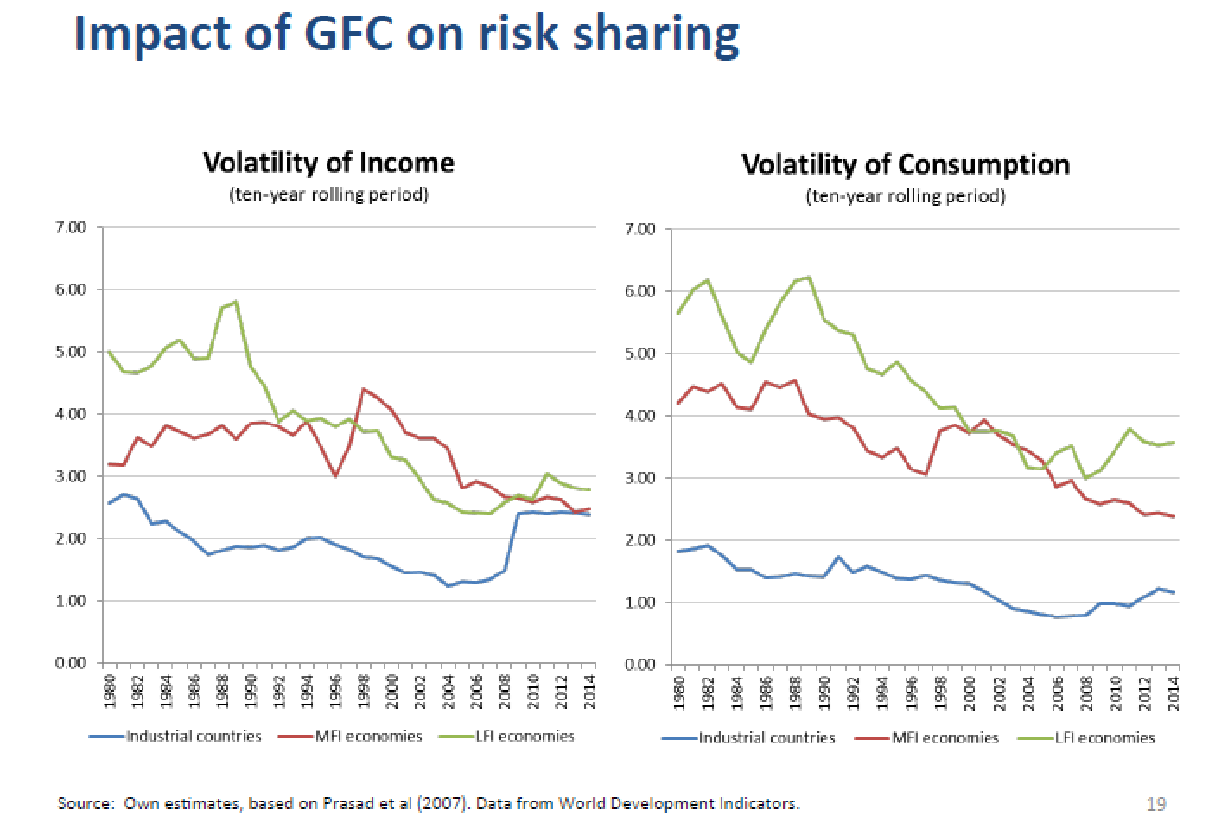

Capital markets did not redistribute wealth or capital stock across countries. Moreover, capital flows to emerging markets have been procyclical which amplified the volatility of their income and consumption rather than smoothed it. The volatility of income and consumption had been long falling because of better business cycle management, but after 2008 crisis increased again.

In the aftermath of the financial crisis there has been a huge slowdown in the financial flows, especially in the financial flows between banks.

I think both academics and policy makers were looking for risks in the wrong place. We focused on aggregate global capital flows but there was not much work on the composition on those flows. And EM crises provided some clues that financial market regulation could be important.

We are now rethinking our view on capital markets integration after the 2008 crisis. Now there is an understanding that financial sector is paramount and there should be much more of financial sector regulation – so policy assumes the central role.

Specifically, capital controls have reemerged as an effective tool while they were a taboo under the “Washington consensus”.

What capital controls can do to help manage capital flows? They can “buy time” and provide a buffer for an economy to deal with weaknesses in the financial sector and to introduce necessary reforms.

So, now the pendulum has moved to the more optimistic view on capital controls but I would take this with a bit of caution. First, by having capital barriers there you make the need to introduce reforms less pressing. Second, economic agents are taking positions incorporating those capital controls, eventually making it harder both politically and economically to take those controls away.

There has been a discussion that capital controls are useful as a temporary measure but there is the time consistency issue. And there has been no development in theory or in practice about the optimal sequence of taking them away and about commitment to lifting capital constraints ex ante.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations