Corruption and lack of clear-cut rules of the game turned the Ukrainian politics into a tool for monetization and protection of business interests. Will the Law on the Public Funding of Political Parties be able to mend the situation? Can Ukraine afford such an instrument?

2016 may go down in the history books on modern Ukrainian politics as a year when the Law on the public funding of Ukrainian parties came into operation. Put simply, from now on, major political forces receive budget funds. According to the law initiators, introducing and implementing this law will help break the oligarchical and kleptocratic structure of the Ukrainian political elite. The opponents of the law, Opposition Block and Radical Party, claim it to be inefficient and wasteful and thus inappropriate regarding the poverty of the most disadvantaged groups of society.

VoxUkraine studied the global practice of funding of political parties and compared the numbers of how much should politics cost and how high a “political tax” in Ukraine is.

Law and Order

The Law on preventing and fight against corruption adopted on October 8, 2015, is aimed at reducing the dependence of political parties from financing by private donors. According to the law, each party which polled more than 2% of votes in the parliamentary elections has right to be financed from the state budget. The amount of funding is calculated using the following formula:

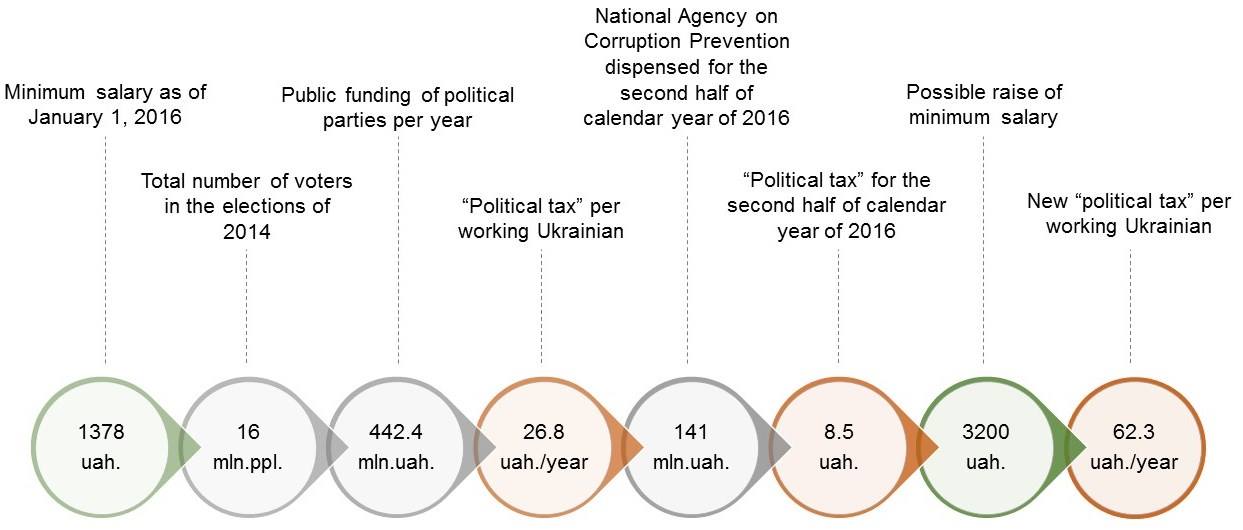

Amount of funding = 2% * (minimum salary)* (total number of voters)

If the law had come into operation on January 1, 2016 and not on July 1, the amount of funding would have amounted to over 442 mln UAH and 26.8 UAH per capita. The National Agency on Corruption Prevention dispensed the funds (141.6 mln UAH) for the second half of calendar year of 2016, that’s why the “political tax” amounted to mere 8.5 UAH. Due to the minimum salary increase to 3200 UAH, the tax will raise to 62.3 UAH.

Figure 1. “Political tax” in Ukraine

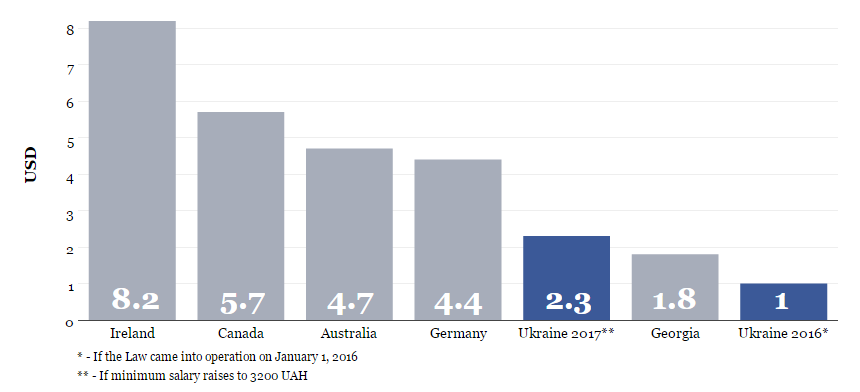

Is 26.8 UAH or 62.3 UAH a high price for democracy or not? Global experience proves that development of efficient democratic institutions cost a bit more.

In Germany, which is one of the leaders of European politics, political parties which polled 0.5% at the national level and 1% at the district level are funded from taxes. In 2009, the German Federal Government allocated 183 mln USD for political activities. According to the World Bank, the labour force in Germany exceeded 42 mln people in 2014. Calculated as per capita, a “political tax” in Germany amounts to 4.4 USD.

Canada, which has one of the best political systems in the world, funds the parties which received 2% of votes in the parliamentary elections or 5% of votes in the local elections. 112.6 mln USD per year were paid to politics from the taxes of 19.7 mln of Canadian working population.

In Australia, state reimbursement was introduced back in 1984 to reduce dependence on big corporations. Nowadays, election funding is provided to parties polling at least 4% of votes. According to the results of the last elections, 58 mln USD were paid from the budget.

In Georgia, public funding allows even small parties to survive in big politics. Following the last elections, 20 parties receive funding totalling 3.6 mln USD, which equals to 1.8 USD per working citizen.

There is an apparent global trend towards the introduction of direct state subsidies. The countries which don’t practice them discuss whether they should be introduced or not. Establishing equal conditions in a competitive electoral environment is necessary to maintain democracy, while the amount of public funding tends to increase.

Figure 2. “Political tax” per working person around the world

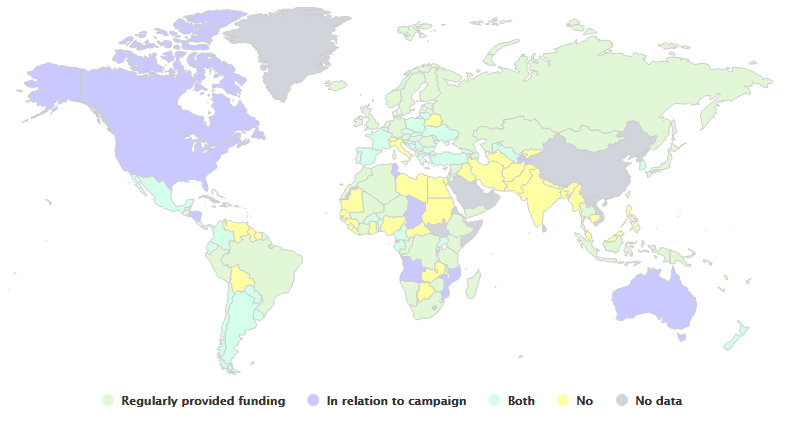

Public Funding of Political Parties around the World

Around the globe, in countries with well-established political systems it is more common for political parties to be funded through the donations of private citizens, while public funding is only used to regulate the political system. To cope with the need to establish democratic political institutions, most countries adopt legislative acts regulating the funding of political parties. There are also common practices of limiting parties’ expenses on political advertising and of post-election reimbursement. The amount of allocated funds is often based on the number of votes for a particular party in the elections. International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance calculated that globally, 21% of countries with direct public funding use a threshold for all such funding based on votes received (on average 3.5%), while 18% limit funding to parties with representation in parliament, and 15% use a combination of these two criteria. Since the 1960s, Western countries were the first to see the need for public funding because strict laws and regulations are not sufficient for providing control (and transparency) over funding political activities.

Figure 3. The provision of direct public funding for political parties

Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance

Pros and Cons of Public Funding

Most countries of the world practice public funding of political parties in one form or another. However, it doesn’t mean there’s no reasoned discussion among supporters and opponents of the idea of public funding.

Valid pros include:

- Expenses on public funding are necessary for a democratic political system. Political parties need money for their statutory activities, communication with voters, and paying to employees. If a country strives for sustainable and independent political parties, it should be ready to support them financially.

- Supporting parties with public funding will limit the influence of oligarchs and help fight corruption. If political parties receive at least partial funding from the budget, it will reduce the need to cooperate with oligarchs and industrial-financial groups which wouldn’t be able to influence their behavior and rhetoric in the Parliament.

- Requirements for receiving the public funding encourage parties to be gender sensitive. The state can regulate participation of males and females in a party by the Law. For example, the number of representatives of one sex should not exceed 2/3 of the total number of party members.

The opponents of the public funding focus on the following statements:

- According to the remaining status quo, big organised parties stay in power. Big parties in power can legislate increasing threshold for parties to receive public funding. Such a situation poses risks for new parties of not receiving a necessary support from the state. Moreover, the parties can raise the amount of public funding.

- Through public funding taxpayers support political parties and views they don’t accept. Opponents of public funding highlight that taxpayers should decide on their own which party to support with their private donations.

- The funds for the public funding of political parties could go to the infrastructure recovery, building hospitals and schools, and not to rich politicians. The state should meet many challenges with available limited resources. Not everyone considers funding of political parties to be on the list of top-priority expenditure items.

Public funding was one of the conditions for liberalisation of the visa regime with the EU. Along with its opportunities, the law poses new risks which can be minimised through combining the public and private funding. For example, Germany practices a ‘matching grants’ mechanism in which public subsidies can never be higher than the amount raised by the party itself. Such a mechanism should be coupled with a continuing monitoring of activities of political parties by an authorised state agency (the National Agency on Corruption Prevention) together with enhancing efforts of NGOs with monitoring functions (“watchdogs”). At the same time, public funding should be sufficient to cover at least basic needs of any party that has reached a certain threshold of public support to let the party fulfil its main functions of promoting civic engagement and representing citizens’ interests.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations