Populist politicians argue that protectionism or the protection of domestic producers stimulates economic growth and reduces trade deficits. Alessandro Barattieri and co-authors use data on temporary trade barriers as a result of antidumping investigations and show that when small open economies apply protectionist policies, this can improve trade balance, but at the expense of higher inflation and recession. Protectionism is an expensive pleasure for small open economies, even if it is applied temporarily and even without taking into account the price of the revenge of trading partners.

Firstly published at VoxEU.

Global concern over a new era of protectionism has been making headlines. The consequences of protectionism dominated policy debates after the Trump administration withdrew the US from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), started renegotiating the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and imposed punitive tariffs against many trading partners.

Like-minded political leaders in other countries make no secret of their appetite for protectionism. They argue that trade policy restrictions can be an effective macroeconomic policy tool, stimulating the domestic economy by reducing trade deficits.

Research has been published on almost every aspect of the consequences of trade policy for international trade. It focuses on trade volumes, gains from trade, firm and industry outcomes (productivity, costs, markups, and misallocation), labour market effects (wages, employment, and inequality), and long-run aggregate growth (for a survey, see Goldberg and Pavcnik 2016).

Trade policy and the macroeconomy

Less is known about the effectiveness of trade policy as a macroeconomic policy tool, though Mundell (1961), Krugman (1982), and Eichengreen (1981, 1983) made important contributions. In the context of the traditional IS-LM model, Mundell and Krugman warned against the potential recessionary effects of protectionist trade policies under flexible exchange rates. Eichengreen (1981, 1983) reached the opposite conclusion by studying a portfolio balance model of exchange rate and macroeconomic dynamics. Perhaps motivated by a trend toward trade integration, academic interest then shifted to the study of the dynamic consequences of reductions in trade barriers, rather than analysing the effects of (possibly temporary) increases in protectionism.

In our recent work (Barattieri et al. 2018), we re-visit the macroeconomic effects of temporary protectionist shocks, both empirically and theoretically.

We use new evidence using data on antidumping investigations from the Global Antidumping Database (GAD), created and maintained by Bown (2016). Antidumping initiatives account for between 80% and 90% of all temporary trade barriers across countries. The GAD database provides information on the date on which antidumping investigations begin, their outcomes (the imposition of antidumping tariffs), and the products involved. Importantly, the data are recorded daily, and so the GAD makes it possible to build time series of trade policy actions at any frequency lower than, or equal to, daily.

We explore the effects of temporary trade barriers by estimating structural vector auto-regressions (VARs) on data from the GAD and standard macroeconomic time series. We consider both monthly and quarterly frequencies. Following Bown and Crowley (2013), our baseline measure of trade policy is the number of HS-6 products for which an antidumping investigation begins in a given quarter or month.[1] We include standard macroeconomic variables: a measure of real economic activity (GDP growth for quarterly data and the log-deviation of industrial production from trend for monthly data), CPI inflation, and the ratio of net exports over GDP.

The frequency of the data and institutional features of antidumping investigations allow us to disentangle the effects of protectionism on macroeconomic outcomes from the reverse effect of business cycle dynamics on cyclical use of trade policy (documented, for instance, by Bown and Crowley 2013). In particular, the opening of antidumping investigations involves decision lags stemming from technical aspects of regulation and coordination among producers. A new investigation requires filing a petition (supported by a minimum number of producers) that gathers evidence about dumped imports and a preliminary assessment of compliance. For this reason, our identifying assumption is that antidumping initiatives do not respond to macroeconomic shocks within a month or a quarter (a contemporaneous exogeneity restriction).

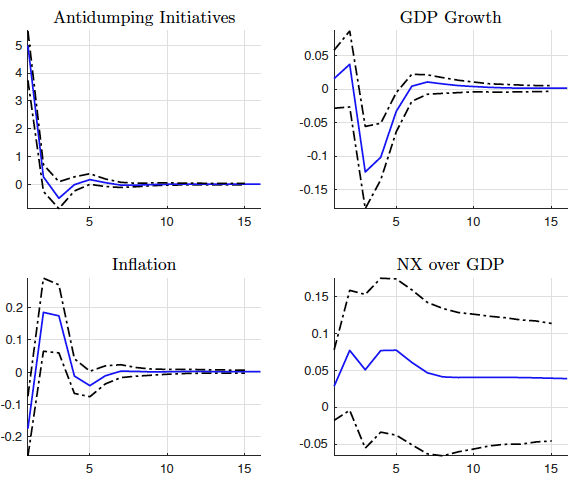

We focus on Canada and Turkey, two of the most active users of temporary trade barriers between 1994 and 2015. Figure 1 shows the impulse responses (and confidence bands) of a one-standard-deviation increase in antidumping initiatives in Canada from the quarterly VAR.

Figure 1 Quarterly VAR, one-standard-deviation increase in antidumping initiatives in Canada

Source: Barattieri et al. (2018).

Note: GDP growth and net exports over GDP are in percentage points. The inflation rate is annualised.

The key finding for Canada is that protectionism has effects similar to an unfavourable supply-side shock. Inflation rises and real economic activity falls. The effect on the trade balance-to-GDP ratio is positive but not statistically significant. We find similar qualitative results for Turkey, except that now the trade balance-to-GDP ratio displays a statistically significant improvement.

These results are robust to a variety of robustness checks, including the use of monthly data, an alternative identification of trade policy shocks, and additional controls for variables that are informative about expectations on future expected economic conditions. Results are similar for India, another active user of temporary trade barriers in the past 20 years.

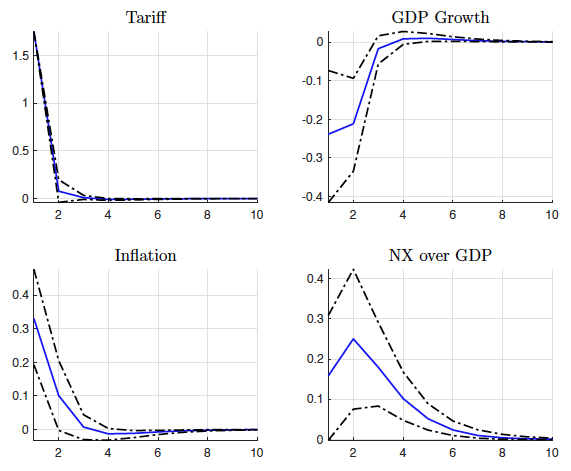

Since antidumping investigations focus on a subset of imports, we also performed an additional empirical exercise in which we used a weighted average of applied tariff rates, which is a more representative measure of trade protection. Since tariff data are available only at annual frequency, we estimated a panel VAR on 21 small open economies that operated under flexible exchange rate regimes between 1999 and 2016. Also, in this case, we focused on real GDP growth, CPI inflation, and the trade balance over GDP. Figure 2 shows results similar to the country-level analysis: the trade-balance-to-GDP ratio improved temporarily, but this was at the cost of higher inflation and lower economic activity.

Figure 2 Panel-VAR for 21 countries, impulse responses to a one-standard deviation increase in detrended tariffs

Source: Barattieri et al. (2018).

Notes: Tariffs, GDP growth, and net exports over GDP are in percentage points. The sample includes Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Iceland, Indonesia, India, Israel, South Korea, South Africa, Malaysia, Mexico, Norway, New Zealand, Peru, Philippines, Paraguay, Thailand, Turkey, and Uruguay.

A benchmark model

We also develop a benchmark small open economy model of international trade and macroeconomic dynamics that allows us to investigate what determines the dynamic effects of protectionism. The model combines key ingredients from the international business cycle literature (endogenous physical capital accumulation and nominal rigidities) with a full endogenous trade structure similar to Melitz (2003) and Ghironi and Melitz (2005).

Consistent with the focus on small economies in our empirical analysis, we assume that one of the two countries in the model is a small open economy with no impact on the rest of the world. We calibrate the model and study the consequences of a temporary increase in protectionism by the small open economy.

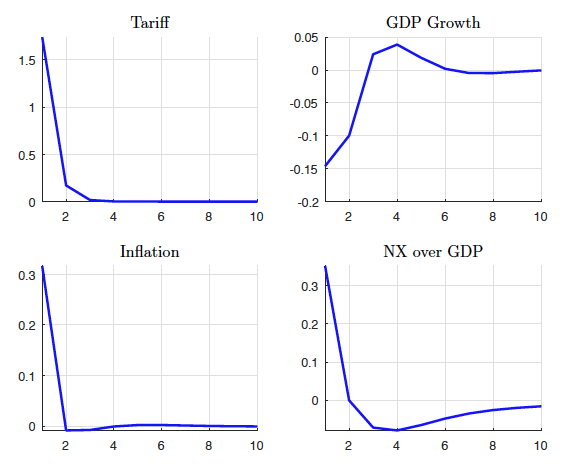

First, we focus on a tariff increase under a flexible exchange rate. This mirrors the empirical analysis described above. The predictions of the model match the robust results of the empirical evidence both qualitatively and quantitatively. Protectionism can generate a small improvement in the trade balance, but at the cost of inflation and recession (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Model-implied, annualised impulse responses to a tariff increase

Source: Barattieri et al. (2018).

Note: The tariff shock matches size and persistence of the equivalent shock in the panel VAR shown in Figure 2. Tariffs, GDP growth, and net exports over GDP are in percentage points.

The model highlights the importance of both macro and micro forces for the inflationary and contractionary effects of tariffs. Higher import prices drive CPI inflation up, and induce expenditure-switching toward domestic tradable goods. Higher tariffs also reallocate domestic market share toward less-efficient domestic producers, lowering aggregate productivity. In turn, higher domestic prices reduce aggregate real income (expenditure reduction), lowering investment in physical capital and producer entry.

Intuitively, since physical capital includes both domestic and imported goods, the import tariff increases the price of investment. Since households spend more of their real income to consume any given amount of imports, the demand for domestic goods declines, reducing the number of producers on the market.

Finally, since the trade shock acts as a supply shock, the central bank faces a trade-off between stabilising output and controlling inflation. When the response to inflation is sufficiently aggressive, the policy rate increases, further depressing current demand. Lower aggregate demand and monetary policy contraction dominate expenditure switching, causing a recession in the aftermath of an increase in protectionism. The trade balance improves, as imports decline more than exports.

Having established that our model successfully replicates the evidence, we then use it to study counterfactual scenarios for which, according to some, the use of temporary trade barriers is potentially beneficial: the presence of a zero lower bound on nominal interest rates (Eichengreen 2016) and the case of a fixed exchange rate (the recent experience of Ecuador, a dollarised economy, illustrates this scenario). Both our empirical evidence and theoretical analysis suggest that protectionism is inflationary. Through this channel, protectionism may help lift economies out of liquidity traps by reducing the real interest rate. In the second counterfactual, in which monetary policy is constrained by an exchange rate peg, the absence of exchange rate appreciation could strengthen the expenditure switching effect of tariffs.

Protectionism is costly

Contrary to basic, partial-equilibrium intuitions, we find that protectionism is contractionary in both counterfactuals. The negative effects of higher tariffs on aggregate investment, and the reallocation toward less efficient producers, continue to dominate other effects. This conclusion is robust under a variety of alternative scenarios.

In sum, protectionism is costly – at least for small open economies – even when it is used temporarily, even when economies are stuck in liquidity traps, and regardless of the flexibility of the exchange rate. The detrimental economic effects arise even abstracting from retaliation from trade partners.

References

Barattieri, A, M Cacciatore, and F Ghironi (2018), “Protectionism and the Business Cycle“, CEPR Discussion Paper 12693.

Bown, C P (2016), Global Antidumping Database, The World Bank.

Bown, C P and M A Crowley (2013), “Import Protection, Business Cycles, and Exchange Rates: Evidence from the Great Recession”, Journal of International Economics 90: 50-64.

Eichengreen, B (1981), “A Dynamic Model of Tariffs, Output and Employment under Flexible Exchange Rates”, Journal of International Economics 11: 341-359.

Eichengreen, B (1983), “Effective Protection and Exchange-Rate Determination”, Journal of International Money and Finance 2: 1-15.

Eichengreen, B (2016), “What’s the Problem with Protectionism?” Project Syndicate, 13 July.

Ghironi, F and M J Melitz (2005), “International Trade and Macroeconomic Dynamics with Heterogeneous Firms”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 120: 865-915.

Goldberg, P and N Pavcnik (2016), “The Effects of Trade Policy”, prepared for the Handbook of Commercial Policy, edited by K Bagwell and R Staiger (2016).

Krugman, P (1982), “The Macroeconomics of Protection with a Floating Exchange Rate”, Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy 16: 141-182.

Melitz, M J (2003), “The Impact of Trade on Intra-Industry Reallocations and Aggregate Industry Productivity”, Econometrica 71: 1695-1725.

Mundell, R (1961), “Flexible Exchange Rates and Employment Policy”, Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science 27: 509-517.

Endnotes

[1] HS-6 stands for Harmonised System Six-Digit. It is the most detailed level of standard disaggregation in the code system used by the World Customs Organisation to define products.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations