This study examines the effects of the ongoing war on interpersonal trust within Ukrainian society.

The key finding suggests that the conflict contributes to a decline in trust, primarily due to its various adverse impacts on individuals. However, the broader institutional context of the country influences the extent to which individuals feel affected by the war. Those who report higher levels of trust in public institutions tend to demonstrate greater resilience to the war’s negative effects on various dimensions of their lives.

The ongoing war with Russia is undeniably affecting all segments of Ukrainian society. Beyond its individual consequences, war also has the potential to reshape collective cooperative behaviour by influencing trust among the population (Rohner et al., 2013). Interpersonal or social trust—commonly defined as the belief that others will act reliably and keep their commitments—is assumed to be shaped by the perceived risks inherent in trusting relationships (Dohmen et al., 2012; Molm, et al., 2000). Armed conflict can substantially alter these risk perceptions, changing the overall level of trust within society (Fiedler, 2023).

A substantial body of research suggests that the influence of conflict on interpersonal trust tends to be primarily negative (Cassar et al., 2013). Trust, in particular, appears to decline significantly in regions directly affected by violence, primarily due to post-traumatic stress disorder or destroyed social ties (Lewis & Topal, 2023). As such, individuals who identify as victims of war frequently report lower levels of trust in others.

In contrast, other studies highlight a potential positive association between conflict and trust (Bellows & Miguel, 2009; Hall & Werner, 2022). Their findings show that individuals who have been more heavily exposed to violence or victimization during war may demonstrate increased prosocial behaviour compared to those with lower exposure (Gillian et al., 2014).

To reconcile these contradictory findings, several studies distinguish between in-group and out-group trust, suggesting that conflict may enhance interpersonal trust within in-groups while diminishing trust toward out-groups (see Fiedler (2023) for a comprehensive literature review). Accordingly, trust in individuals from one’s own community is assumed to remain stable or even increases during conflict, whereas trust toward those outside the community tends to decline and may stay low even after the conflict ends.

This research investigates the impact of war on trust in others by examining the case of Ukraine. As a post-communist society, Ukraine has traditionally exhibited moderate levels of interpersonal trust. The question is whether the ongoing war could further reduce individuals’ trust to compatriots, and if so, through what mechanisms this effect occurs.

The analysis draws on original survey data collected by Research.ua LLC in November 2024. The sample includes 850 respondents aged 16 to 55, with the age boundaries reflecting the specific focus of a broader research project from which this dataset has been derived. A detailed description of the survey is available here.

Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) is employed as the primary methodology for empirical investigation as it enables the simultaneous estimation of relationships among multiple variables, including both observed (measured) and latent (unmeasured) ones. In particular, some variables in this study, such as the experience of war, cannot be measured directly with only one question. Instead, it is measured using several related questions or indicators. SEM combines these indicators to represent the overall idea underlying the variable more accurately. In this way a latent variable is estimated through other information. Furthermore, SEM allows the estimation of both direct and indirect effects between two or more variables, enabling the modeling of all the different ways in which conflict might influence people’s trust in others.

In this analysis, the response variable is interpersonal or social trust (STr), measured through a conventional question asking respondents to specify whether one can trust strangers or one should be careful in dealing with them. The response scale varies from 1 to 7, with higher values reflecting greater trust in others.

In modeling interpersonal trust formation, trust is viewed as an outcome of both individual and contextual resources available within society. Individual resources refer to factors under the direct possession or control of individuals that may influence their trust level through their willingness to take risks. For example, education is associated with greater trust, as more educated individuals are often more inclined toward risk-taking (Delhey & Newton, 2003). Similarly, individuals with greater financial resources are generally more trusting, as their material security reduces the perceived cost of potential trust violations (Bjornskov, 2005).

Considering this multitude of individual resources, they are modelled as a latent variable, using three observable indicators: (a) Education level (Edc), coded from 1 (“Incomplete secondary education”) to 7 (“PhD degree or similar”); (b) Household monthly income (Inc), coded from 1 (“Less than 5,000 hryvnias”) to 5 (“More than 50,000 hryvnias”), and (c) Overall financial situation (Wlt), coded from 1 (“There is not enough money even for food”) to 6 (“Our family can easily buy a house or an apartment”).

Similarly, contextual resources refer to contextual conditions that shape the level of risk associated with trusting others in society. Literature commonly highlights the role of institutions, such as the legislative process, the sanctioning system, and the effectiveness of law enforcement (Rus, 2005), as key factors in promoting interpersonal trust. These institutions are able to reduce the risks associated with interpersonal trust by ensuring accountability and punishing breaches of trust-based expectations (Rothstein & Stolle, 2010). In line with this perspective, the contextual component is modelled as a latent variable by using respondents’ self-reported trust in the government (TrG), courts (TrC), and police (TrP). Each of these is assessed using a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“No trust at all”) to 7 (“Complete trust”).

The impact of war is also modelled as a latent variable, since it represents a complex experience that cannot be captured by a single question. Instead, it is estimated using several self-reported indicators that reflect individuals’ psychological and behavioral responses to the ongoing conflict. These indicators include (a) MhC – the perceived effect of the ongoing war on mental health (ranging from 1 = “Deteriorated a lot” to 6 = “Did not change at all”); (b) Sft – current perceived level of personal security (1 = “Feel entirely unsafe” to 7 = “Feel entirely safe”); and (c) Alt – the degree of altruistic orientation (1 = “I do not feel obliged to help others during the war” to 7 = “I feel obliged to help others during the war”). All items are coded such that higher values reflect greater resilience to the effects of war. Additionally, a measure of alignment with the war scope (UAU) is included, captured by respondents’ assessment of how important they consider it for Ukraine to restore its territorial unity (1 = “Not important at all” to 7 = “Very important”). Higher values are assumed to reflect more alignment with the in-group, while those who choose lower values are considered part of the out-group.

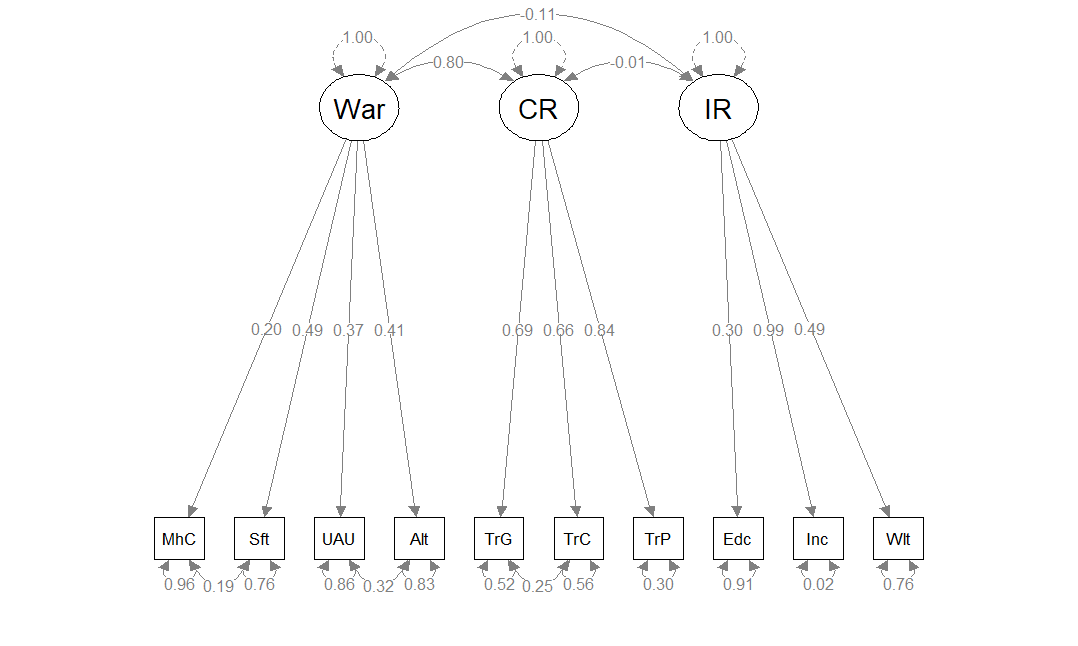

The measurement model for the three latent constructs is shown in Figure 1, including individual resources (IR), contextual resources (CR), and impact of war (War). Each of these latent variables represent an unobservable construct inferred from the commonality in the variances among the observed items which were selected for their estimation. In particular, the latent variable “War” is defined by mental health deterioration (0.20), perceived safety (0.49), territorial unity (0.37), and altruism (0.41), while contextual resources (CR) are strongly predicted by trust in the police (0.84), government (0.69), and courts (0.66). Individual resources (IR) are most strongly associated with income (0.99), followed by wealth status (0.49) and education (0.30). The numbers in brackets represent standardized factor loadings, measuring the strength of the relationship between each observed item and its underlying latent variable, with higher values denoting stronger associations.

Additionally, a strong and statistically significant covariance (0.80) is observed between the war construct and contextual resources (see the curved arrow between War and CR in Figure 1). While the causal direction is not specified, the positive relationship between these two latent constructs is consistent with the theoretical understanding that war can deteriorate trust in various public institutions. Individuals may attribute the failure of protecting them from the enemy or negative consequences of war to public institutions, reducing trust in them (Fiedler (2023). By contrast, covariances between the war construct and individual resource variables, as well as between individual and contextual resources, are not statistically significant.

Figure 1: Path diagram for the measurement model

Notes: The standardized estimates are reported for the paths. The interpretation is as follows: For example, the latent variable “individual resources” is measured through three observed items: respondents’ education level, household income, and overall financial situation. This latent construct shows a correlation (loading) of 0.30 with education, 0.99 with income, and 0.49 with financial situation. Those correlations reflect how strongly each observed item is associated with the underlying latent variable. They are calculated through the maximum likelihood estimation based on the commonality in variances among the observed items. The numbers displayed under each item represent the unexplained variance—that is, the portion of each indicator not accounted for by the latent variable. For instance, only 2% of the variance in income is unexplained by individual resources, meaning that income is very closely aligned with the latent construct. In contrast, 91% of the variance in education is unexplained, suggesting it is less directly tied to this latent factor. The residual or unique variance for each item is calculated as follows: For instance, if the factor loading of education on the latent variable “individual resources” is 0.30, squaring this loading (0.30² = 0.09) indicates that only 9% of the variance in education is explained by the latent factor, leaving 91% as residual variance. Lastly, the numbers on the curved arrows between the latent variables represent the standardized covariances between these underlying constructs.

Overall, the model (M1) demonstrates a satisfactory fit to the data (see row M1 in Table 1), supporting the validity of the measurement approach. To achieve this satisfactory fit, three additional correlations were introduced (Figure 1): First, a correlation was allowed between confidence in government and confidence in courts, reflecting the theoretical and empirical overlap in trust toward various institutions. Second, a correlation was added between perceived deterioration in mental health and safety in one’s place of residence, acknowledging the likely interdependence between psychological well-being and personal security. Third, a correlation was specified between support for Ukraine’s territorial unity and levels of altruism, based on the assumption that a stronger identification with the war is associated with a stronger sense of collective responsibility. These modifications are theoretically grounded and do not compromise the model’s validity. In fact, some degree of local dependence between the items of the same construct can be expected when they share conceptual or empirical proximity (Bauer & Curran, 2019).

Table 1: Summary of fit statistics for estimated models

| χ2 | df | CFI | TLI | AIC | BIC | SRMR | RMSEA (95% CI) | |

| M1 | 87.81 | 29 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 29029.56 | 29200.39 | 0.034 | 0.049 (0.037-0.061) |

| M2 | 105.54 | 37 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 32151.27 | 32341.08 | 0.034 | 0.046 (0.036-0.057) |

Notes: M1 corresponds to the model visualized in Figure 1, while M2 refers to the model presented in Figure 2. CFI: comparative fit index; TLI: tucker-lewis index; AIC: akaike information criterion; BIC: bayesian information criterion; SRMR: standardized root mean square residual; RMSEA: root mean square error of approximation.

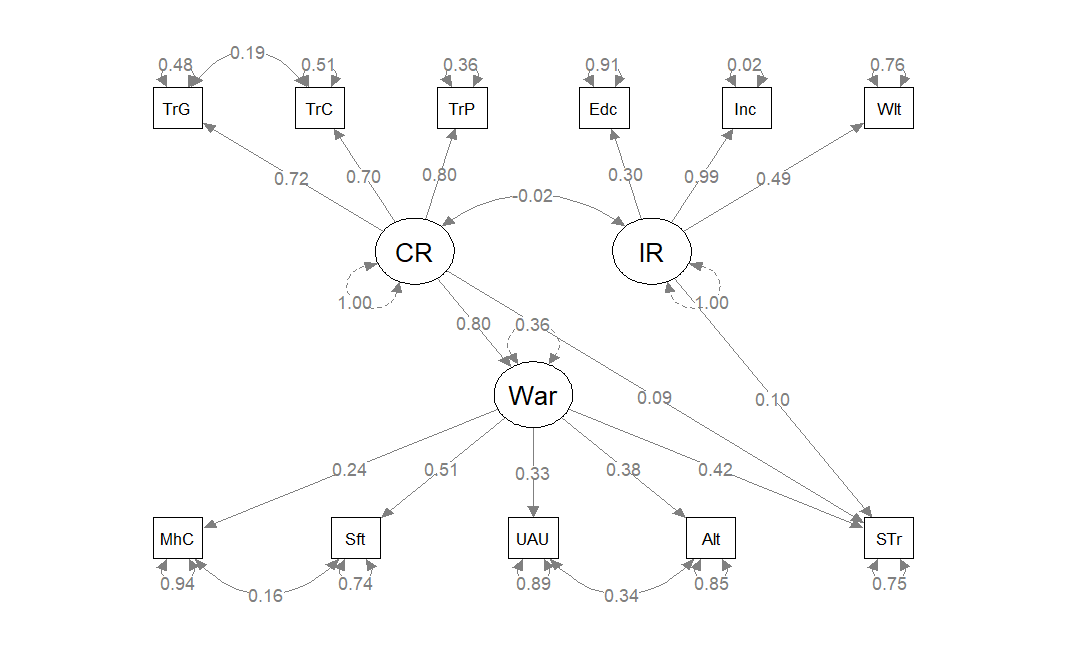

Lastly, a structural model has been estimated. The model that could yield a satisfactory fit (see M2 in Table 1) is visualized in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Path diagram for the structural model

Notes: The standardized estimates are reported for the paths. The numbers adjacent to the observed items and latent variables represent the residual variances. For identification purposes, the means of the latent factors are fixed to 0, and their variances are fixed to 1.

In this structural model, social trust is significantly predicted by both individual resources (β = 0.10, p = 0.002) and war (β = 0.42, p = 0.003), while contextual resources have no statistically significant direct effect (β = 0.09, p = 0.550). However, contextual resources strongly predict war-related experiences (β = 0.80, p < 0.001). This is likely due to the fact that conflict increases both risks and costs for individuals, while the institutional framework determines how these burdens are distributed across the population. When institutions are exclusionary—benefiting only a select few—citizens tend to experience greater stress, insecurity, and a diminished sense of belonging to the state. As a result, they are less inclined to support others who might benefit from these biased institutions. In contrast, when institutions are inclusive and equitably distribute the risks and costs associated with conflict, citizens perceive themselves as equal members of society. They are more likely to believe that the state will protect them regardless of their individual characteristics, which in turn reduces the perceived personal impact of war. Lastly, covariances between individual and contextual resources are low which suggests that they function as distinct constructs in the model.

Table 2 summarizes the above mentioned factor loadings and covariances, suggesting that the ongoing war significantly impacts interpersonal trust within Ukrainian society. The coefficient for this effect is positive (0.42), indicating that individuals who perceive themselves as less affected by the war tend to exhibit higher levels of trust in others (the arrow from War to STr). Conversely, those who feel more intensely affected by the war are more likely to display lower levels of interpersonal trust. However, the broader context of the country, measured through trust in the selective public institutions, influences the extent to which individuals feel affected. Those who express confidence in institutions tend to feel more resilient to the effects of the war on various aspects of their life (the arrow from CR to War).

Table 2: Factor loadings and correlations for the structural model depicted in Figure 2

| Standardized loadings | z-value | P(>|z|) | |

| Latent variables | |||

| War =~ | |||

| Mental health deterioration (MhCh) | 0.244 | 3.873 | 0.000 |

| Perceived safety (Sft) | 0.512 | 4.941 | 0.000 |

| Important to restore territorial unity of Ukraine (UAU) | 0.328 | 4.617 | 0.000 |

| Altruism (Alt) | 0.384 | 4.875 | 0.000 |

| CR =~ | |||

| Confidence in the government (TrG) | 0.721 | 19.427 | 0.000 |

| Confidence in courts (TrC) | 0.700 | 18.742 | 0.000 |

| Confidence in the police (TrP) | 0.800 | 22.130 | 0.000 |

| IR =~ | |||

| Education (Edc) | 0.297 | 6.881 | 0.000 |

| Income (Inc) | 0.989 | 10.579 | 0.000 |

| Wealth status (Wlt) | 0.489 | 8.893 | 0.000 |

| Regressions | |||

| Social trust (STr) ~ | |||

| Individual resources (IR) | 0.103 | 3.112 | 0.002 |

| Contextual resources (CR) | 0.094 | 0.597 | 0.550 |

| War (War) | 0.416 | 2.960 | 0.003 |

| War ~ | |||

| Contextual resources (CR) | 0.797 | 4.645 | 0.000 |

| Covariances | |||

| Confidence in the government (TrG) ~~

Confidence in courts (TrC) |

0.185 | 2.760 | 0.006 |

| Mental health deterioration (MhCh) ~~ Perceived safety (Sft) | 0.165 | 3.814 | 0.000 |

| Important to restore territorial unity of Ukraine (UAU) ~~ Altruism (Alt) | 0.340 | 8.110 | 0.000 |

| Contextual resources (CR) ~~ Individual resources (IR) | -0.024 | -0.614 | 0.539 |

Notes: The “Latent variables” section displays factor loadings, which quantify how strongly each observed item (e.g., education, income, etc.) is associated with its underlying latent construct (e.g., War, Contextual Resources (CR), Individual Resources (IR)). The “Regressions” section presents standardized regression coefficients, indicating the directional relationships between variables as specified by the tilde symbol “~”. Finally, the “Covariances” section lists covariances, reflecting the degree to which two latent variables covary without implying a causal relationship.

Drawing upon the above findings, the ongoing war can be expected to reduce trust among Ukrainians, which is not surprising given the multiple negative effects that the current conflict produces on individuals, including deteriorations in mental health, sense of insecurity, etc. Interestingly, the local dependence between these subscales (items) may provide additional insights: On the one hand, perceived safety in one’s place of residence is positively correlated with mental health deterioration (0.16), as shown in Figure 2. Since mental health is measured on a reverse scale, the positive estimate suggests that individuals who feel safer are less psychologically affected by the war. This aligns with previous research indicating that mental health is often severely impacted by conflict (Kurapov et al., 2023).

On the other hand, the positive correlation of 0.34 between the individuals’ opinion on maintaining Ukraine’s territorial unity and their level of altruism (see Figure 2) suggests that those who are more committed to the idea of the return of all the occupied territories are more likely to exhibit a stronger propensity to help others and cooperate during the war. This is consistent with existing studies showing that altruism tends to increase during wartime, particularly among in-group members united by a common cause, such as resistance against a shared enemy (Rohner et al., 2013).

In summary, the results suggest that the war is likely to lead to a decline in social trust among the population of Ukraine. This decline is dangerous as it can have significant consequences for social cohesion within Ukrainian society. However, as the analysis indicates, improving the quality of institutions could enhance the trust-building process by mitigating the adverse impacts of war. By making state institutions more inclusive and responsive to citizens’ needs, the government can limit the negative effects of the war, rebuilding public confidence and fostering a more prosocial culture. Such policies would increase the collective effort for a rapid and effective reconstruction of the country.

Photo: depositphotos.com/ua

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations