Last week, United States Institute of Peace had a round table to discuss three important questions about how to economically re-integrate the Donbas back into Ukraine when U.N. Peacekeeping Force arrives to the territory occupied by Russian backed rebels. We participated in this round table along with other KSE and VoxUkraine affiliates. In this post, we provide an overview of thoughts expressed by us and other participants.

Question #1: What has been the impact of the war in the Donbas on the economy of the regions of Donetsk and Luhansk, and on the national economy of Ukraine? And, how has the economy of the region affected the war?

We have good data to document that the war in the Donbas was very costly for the rest of Ukraine. For example, production chains linking the suppliers/buyers across Ukraine were disrupted thus contributing to in a large economic downturn. In similar spirit, the financial sector had a high exposure to the Donbas economy which nearly destroyed the sector. Indeed, Ukrainian banks’ liabilities to residents of the Donbas are still recognized but loans issued to households and firms in the Donbas quickly became non-performing. As a result, all Ukrainian banks had negative capital which greatly limited their ability to credit the economy in parts of the country not affected by the war directly. Ukraine also lost a significant source of fiscal and export revenue. All of these led to panics and runs on the hryvnia and the banks further exacerbating the crisis. The freefall of the economy was eventually stopped and the Ukrainian economy is on a recovery trajectory but it will likely take many years before the economy catches up to its prewar level.

In short, the available data for the occupied Donbas are consistent with misallocation of resources and weak economy.

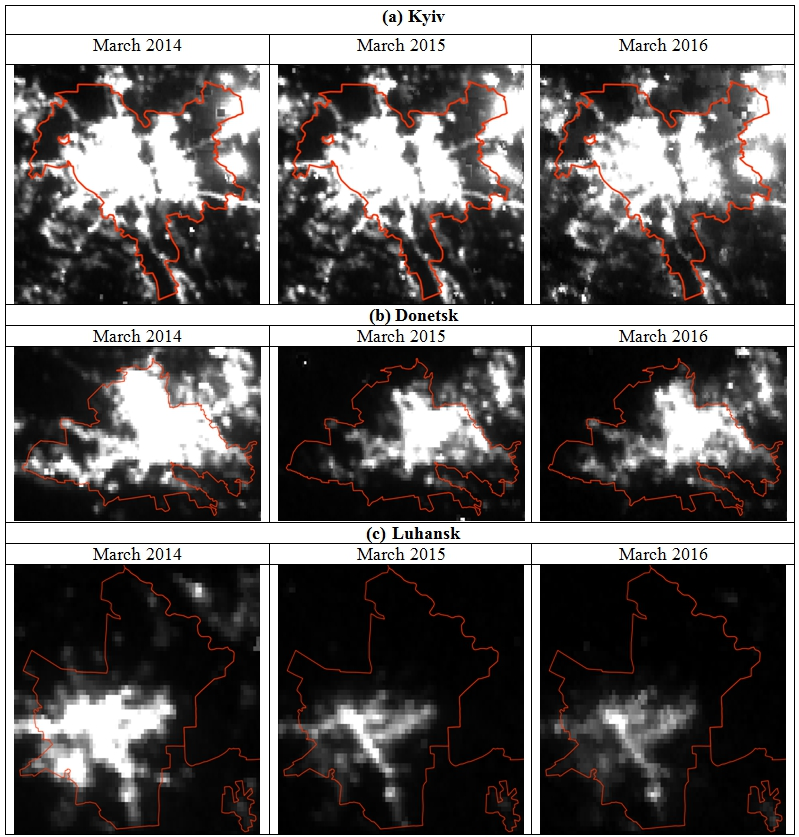

There is much less high-quality information about the state of the economy in the Donbas outside Ukrainian control. However, we have indirect measures of economic activity. For example, a VoxUkraine study documents that nighttime light intensity declined considerably (50-70 percent) in the occupied part of the Donbas. Since light intensity and economy activity are highly correlated, one should expect a massive collapse of economic activity in the occupied Donbas. Another VoxUkraine study documents large price dispersion across cities in the occupied Donbas which is often a symptom of markets not functioning well. Intuitively, price dispersion is generated by local shortages of goods which should not happen if economic activity is not constrained. In short, the available data for the occupied Donbas are consistent with misallocation of resources and weak economy.

Figure 1. Night time images of Kyiv (a), Donetsk (b) and Luhansk (c) in March 2014, 2015 and 2016

Question #2. There’s been much talk about the possibility of a UN Peacekeeping Force and Interim Administration to administer the region for 2-3 years during a transition to Ukrainian control of the territory. What are the economic issues that a UN operation might face?

Obviously, security is the central issue. However, sustained peace is unlikely to happen unless the economy of the currently occupied part of the Donbas takes off. There are numerous issues one should address to restart the economy. First, infrastructure in the occupied Donbas is in an increasingly poor shape due to negligence and willful destruction. Because infrastructure is a backbone for any economy as well as for any large-scale peacekeeping mission, one should prepare resources to rebuild critical infrastructure quickly, especially bearing in mind not only economical but environmental hazards in the region. Significant resources should also be directed to remove landmines and other weapons that jeopardize the lives and the economy in the area.

Because infrastructure is a backbone for any economy as well as for any large-scale peacekeeping mission, one should prepare resources to rebuild critical infrastructure quickly, especially bearing in mind not only economical but environmental hazards in the region.

Second, the future U.N peacekeeping mission should learn from the experience of Ukrainian authorities that regained control over cities occupied at some point by the rebels. In short, the Ukrainian forces saw a humanitarian crisis and the Ukraine government had to address critical shortages of medicine, food, and other basic necessities. Thus, the U.N. should prepare to couple the military force with a large humanitarian aid program.

Third, the temporary administration will have to address a crisis of property rights in the currently occupied Donbas. Indeed, for four years the region was controlled by rebels with their own institutions and notions of ownership. When Donbas residents who are currently displaced to other parts of Ukraine return to the Donbas, they are likely to find that their property is occupied by other people. While Ukraine does not recognize changes in ownership authorized by the rebel, one should expect acute conflicts between former and current owners.

Figure 2. Cross-sectional standard deviation of log (price)

Question #3: What will it take to rebuild Donbas and re-invigorate the economy so that it provides the economic growth and jobs to sustain the peace? What will be required to reintegrate Donbas into the Ukrainian economy?

As we discussed above, sustained peace requires a strong economy. Indeed, research shows that areas where jobs were at a greater risk under the new Ukrainian authorities were more likely to have violence. People in the occupied Donbas should see tangible changes in the quality of their lives and these changes should dispel beliefs about their jobs being at risk. Rebuilding infrastructure can provide many well-paid jobs for current residents. Workers in the public sector (teachers, doctors, etc.) are likely to experience material salary raises as they join the ranks of public sector workers in the “mainland” Ukraine. These and similar elements can give a short-run boost, but one should also contemplate a strategy for a long-run growth. Specifically, the war induced many high-human-capital people to leave the region. They have been away for nearly four years and likely they have started new businesses and settled in their new places. Whether they will want to return is a key question because these people still have local networks and thus they are most likely to be engines of the local economy. A system of incentives (tax breaks, cheap credit, security, etc.) should be in place to give these people reasons to return to their former homes and launch their businesses.

A system of incentives (tax breaks, cheap credit, security, etc.) should be in place to give these people reasons to return to their former homes and launch their businesses.

Another key question is what kind of economy one should be building in the new Donbas. The pre-war Donbas was similar to the Rust Belt in the U.S.: industry in the region largely comprised of declining sectors (coal mines, base metals, etc.). The war destroyed part of the pre-war industry thus clearing a way for a new economy. Ukraine and the Donbas should use this tragedy as an opportunity to build a modern economy rather than a 20th century economy. For example, Pittsburg (an American version of Donetsk) reinvented itself into a major research hub and one should learn from this experience.

In any case, one should expect that rebuilding the Donbas will be expensive. Ukraine does not have resources to pay for it. A coalition of donors to share the burden should be ready before the U.N. forces come to the Donbas so that no day is wasted under the new regime.

Main photo: depositphotos.com / DenysKuvaiev

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations