Once we’ve already caught Mr. Petrashko on a poor command of economic performance and timing. Then, for some reason, he turned a blind eye to several quarters of economic growth in a row in Ukraine and argued that the Ukrainian economy was stagnating.

This time, in the interview for Economichna Pravda, the minister shared his views on economic policy. We were pleased to learn that he is a supporter of European association, privatization and deregulation, and also supports public procurement reform (Prozorro). Moreover, he thinks that targeted projects will not help achieve sustainable economic development. As far as we understand from the interview, the basis for such development Mr. Petrashko considers in large-scale lending to the economy and the development of domestic production due to less liberal foreign trade policy (“we are not for “buy Ukrainian”, but for – “produce in Ukraine” – whatever that means).

However, the practical steps for implementation of such policies, proposed by the Minister, seemed questionable to us. Below are the checks of some (not all) controversial points of the Minister.

About the foreign trade

Manipulation

“From the point of view of the economic format: in 2014-2015 there was a misconception that the liberal foreign market would be fully open and it would work as written in the books. That never happens.

We have completely opened the markets. We, probably, have the worst conditions within the WTO in the world or one of the worst. The model, according to which we completely opened the markets, was built in a wrong way. That is why now we are working with such deplorable consequences.”

Consumers and society as a whole clearly benefit from trade liberalization, as evidenced not only by theoretical models but also by empirical research. Some producers may lose from the opening of markets: those whose goods cannot compete with imports in terms of “price-quality” ratio. And those who do not want to invest in modernization. However, as a rule, such companies have more opportunities to lobby their interests in government and parliament than consumers. Therefore, the issue of “protection of domestic producers” from time to time appears on the agenda.

Ukraine has been negotiating its accession to the WTO for 15 years (1993-2008). During this time, it has implemented most of the WTO rules into national law. Therefore, Ukraine’s accession to the World Trade Organization was not a “shock” for Ukrainian producers. On the contrary, Ukraine has received a better access to the markets of WTO member states and guarantees of maintaining the conditions of this access in the future, access to a mechanism for resolving trade disputes and the ability to influence future rules of international trade. After accession to the WTO, the average weighted import duty rate was reduced from 10.5% to 5.1%. However, certain “prohibition” rates have been maintained, for example, 50% on sugar imports and 30% on sunflower oil. Therefore, it is wrong to talk about the worst conditions of Ukraine in the WTO.

In addition to market access, Ukraine has got many other benefits from WTO membership. For example, the opportunity to accede to the Public Procurement Agreement (according to which Ukrainian suppliers can participate in the procurement of public authorities of other countries), the opportunity to negotiate free trade zones with other countries or their associations, access to the WTO arbitration mechanism, etc. The 2015 IER study shows that for the main sectors of the Ukrainian economy, the impact of WTO accession has been either positive or neutral.

Full liberalization of foreign trade has not taken place even now, after Ukraine signed the Comprehensive Free Trade Area with the EU. This agreement provides for asymmetric conditions that are more favorable for Ukraine. That is, the EU lowered the barriers for Ukrainian products immediately after the signing of the Agreement, while Ukraine was able to open its market gradually.

For example, immediately after the signing of the Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement, Ukraine abolished import duties on 82.6% of industrial goods, and the EU – on 91.8%. Ukraine got the possibility to set transition periods or create special safeguard mechanisms for some goods (e.g. cars). Reciprocal zero duties on industrial goods will apply only after the end of the transition periods.

For agricultural products, the situation is even more favorable for us: duties were immediately abolished on 35.2% of tariff lines by Ukraine and on 83.1% by the European Union. For other goods, Ukraine has introduced transitional periods of up to 7 years, partial liberalization or duty-free tariff quotas. Under the agreement, Ukraine supplies some goods (14.9% of goods are grain, pork, beef, poultry, etc.) to EU markets under duty-free tariff quotas. That is, a certain amount of goods can be supplied at zero duty, and anything above this amount – with the payment of duty.

Thus, the manipulation is that, first, Ukraine has not fully liberalized its foreign trade, and second, we have benefited from such liberalization (see 1, 2, 3), but have not lost.

Manipulation

Petrashko: “In 2004, when I was studying in the United States, exports of Ukrainian goods to foreign markets amounted to about $ 33 billion, and now, 16 years later, it has increased, but not as much as we would like it to.”

Journalist: “Why did it happen?”

Petrashko: “We were squeezed out of the markets. We were like those aborigines with “rattles”. They were bringing us money and were saying: here is your loan, and now buy our buses, our dolls, our cars and everything else. We said: great, how beautiful. At that time, businesses were closing, directions were closing, people were losing their jobs and going abroad. ”

First, we note the logical contradiction in the words of the Minister. At first he says that we were squeezed out of foreign markets (that is, foreigners bought Ukrainian goods less). And then – that this was due to the fact that we were forced to buy imported goods. However, if Ukrainians buy more imported goods, it means that they buy less domestic goods on the domestic market, than on the foreign one. That is, an increase in imports of consumer goods (so-called “rattles”) is not associated with a decrease in exports of Ukrainian metals or fertilizers.

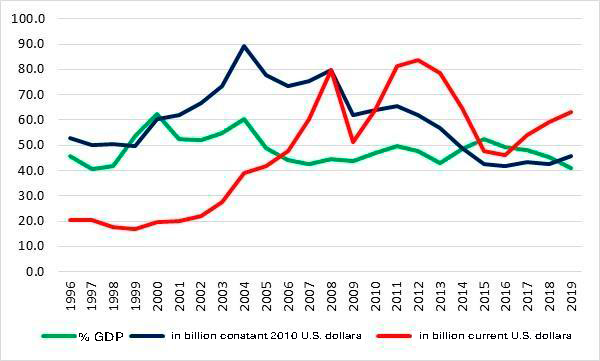

Now let’s consider these points separately. The situation with Ukrainian exports is shown in Fig. 1. We see that in current prices exports have indeed increased compared to 2004, and in constant prices and as a share of GDP, it decreased. The reasons for this are the two economic crises that Ukraine went through (2008-2009 and 2014-2015), and in the latter case the economic crisis took place amidst the Russia’s military aggression against Ukraine, which was accompanied by the loss of territory and assets. It is estimated that assets lost in the occupied territories accounted for 20-25% of Ukrainian exports.

Figure 1. Exports from Ukraine

Source: World Bank according to the State Statistics Service. Data excludes occupied territories for goods since 2014, for services since 2010.

Nobody deliberately pushed Ukrainian goods out of the markets. But the competitive advantage of the main goods of Ukrainian exports (metals, chemical products, agricultural products) was and often remains the price, not quality. Ukrainian producers could offer a low price due to three main factors: cheap labor, cheap energy and government support. Therefore, Russia’s increase in gas prices was a significant blow to the competitiveness of our exporters. Low wages compared to neighboring countries have led to labor migration of Ukrainians. And state support (including in the form of artificial restrictions on competition), although, allows inefficient enterprises to stay afloat, but is generally detrimental to economic growth.

Ukrainian governments have attracted foreign loans to finance the budget deficit. No one has imposed these funds on us, as governments could keep the deficit low or finance it solely through domestic borrowing.

The conditions for the vast majority of loans, for example, from the IMF, the World Bank and other international institutions or governments, was carrying of reforms that Ukraine needed in the first place. However, some loans were indeed provided for the purchase of imported goods (for example, Hyundai trains, trams for Lviv).

And, of course, foreign loans are not the cause of reduced production or labor migration. Businesses have been closing due to the low quality of their products and the poor investment climate, which did not allow them to raise funds for modernization. And the reasons for labor migration are low wages in Ukraine, low quality of public services, dissatisfaction of citizens with the living conditions. Low wages, in turn, are the consequence of low productivity due to outdated technology.

On the monetary policy

False

“If we are talking, say, about crediting, about the same emission of money, all of these are myths. We have no money emission. What is a money emission? The emission of money is when there is an additional issue being held.”

In fact, the central bank regularly carries emissions through currency, stock and credit channels, i.e. when the NBU:

- carries out operations on purchase of foreign currency on the interbank market;

- carries out operations on the open market for the purchase of state securities;

- supports liquidity of the banks through refinancing mechanisms.

Since the beginning of 2020, the NBU has bought $926 million of foreign currency on the interbank foreign exchange market and thus issued about UAH 25 billion. Another UAH 9 billion was issued through refinancing loans, but meanwhile operations were carried out to withdraw money from the economy (it is called sterilization) by selling deposit certificates of the National Bank. Such operations amounted to almost UAH 19 billion. Thus, the “net” emission of money this year amounted to UAH 15 billion (= 25 + 9-19).

False

“Our only target was inflation, which is not the case in any monetary country in the world.”

In the inflation targeting regime, which is currently introduced in 48 countries around the world, the main goal of central banks is inflation. Central banks often have an additional goal – economic growth or low unemployment. The Ukrainian central bank also has additional goals.

Thus, the law on the NBU states that the main goal of the National Bank is the price stability (i.e. low inflation). Other goals are financial stability and economic growth. The National Bank is working to achieve them as long as they do not contradict the main goal. Therefore, the statement that the only target in Ukraine is inflation is incorrect.

About the banking sector

False

“The reform of the banking system is not over. That is, most of our banks, which were problematic in 2014, have remained so. Look, who continues to pay high interest rates. We know how it ends…”

The NBU withdrew most of the troubled banks from the market during 2014-2015. At the end of 2013, there were 180 banks in Ukraine. During the cleanup of the banking system, 104 of them were closed. In 2016, the state recapitalized and nationalized the systemic PrivatBank, and the liquidation of the insolvent Arkada Bank has begun recently. If there were troubled banks in Ukraine today, we would see a “bankfall” during the current crisis. Instead, the banking system is doing well, and this is the result of reforms carried out in previous years.

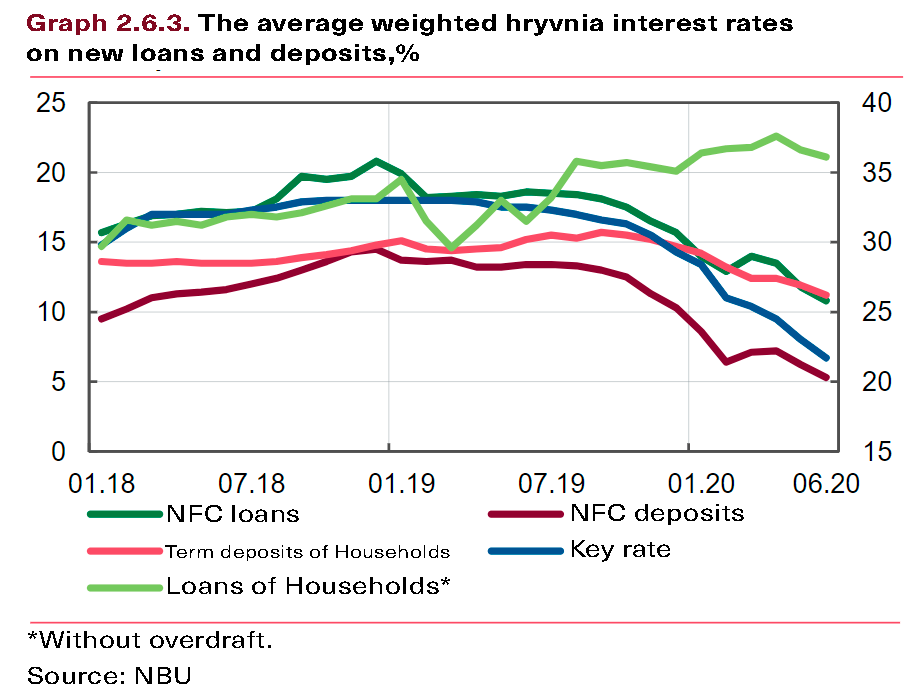

Also, most of the banks have deposit rates close to the market average, and average rates have been falling over the past year.

Manipulation

“Redistribution from the unproductive to the productive sector. Look at the profitability of the banking system over the past years. It goes overboard. Should it be like that? Look at the European Union and the United States: there banks operate at the level of marginal profitability, i.e. have real problems with profitability. Here they go beyond the scale. ”

In fact, the return (i.e. return on assets of the banking system) grew to about 2% only in 2018. Prior to that, while banks were emerging from the crisis, it was below 1% (i.e. approximately the same as in Europe), and in 2016 it was generally negative.

For comparison, from 2016 to 2020, the average return on assets of the banking system of 28 EU countries was 0.4%, the US banking system – 1.08%, and the banking system of Ukraine – 1.41%. And, although, today the return on assets of Ukrainian banks is really higher than in Europe, but there is no reason to say that it is “beyond the scale”. In the EU and the US, bank profits are less volatile than in Ukraine. Therefore, in the long run, Ukrainian banks do not receive excess profits.

The high return on assets is partly due to higher interest rates in Ukraine. But firstly, such rates were needed to reduce inflation (for example, in 2016, the discount rate was reduced too quickly, and inflation immediately rose). Secondly, banking in Ukraine is more risky due to a weak judiciary system and unpredictable policies. Accordingly, banks need to be more profitable in “good times” in order to be able to cover losses at the expense of profits during the next crisis.

Banks cannot lower down their interest rates instantly. But we see that they are gradually lowering rates following the reduction of the NBU discount rate (see graph).

About the public debt

Manipulation

“There is also an extremely expensive public debt. There is no problem that Ukraine has one of the lowest public debt-to-GDP ratios, taking into account the shadow sector. With this in mind, we generally have one of the best figures in the world, not including Asian countries, the Middle East or Russia, which are resource-oriented and do not have a large international debt…. We have the service somewhere at the level of 10-12% at 60% of debt to GDP.”

In this quote, the Minister tries to say that it is necessary to take into account not only the amount of debt, but also the cost of its service, which in Ukraine is higher than in the developed countries. This point is correct, but the Minister provides outdated or inaccurate data in support of it. But he does not explain the objective reasons of the difference in the cost of borrowing for Ukraine and for developed countries. This is the manipulation.

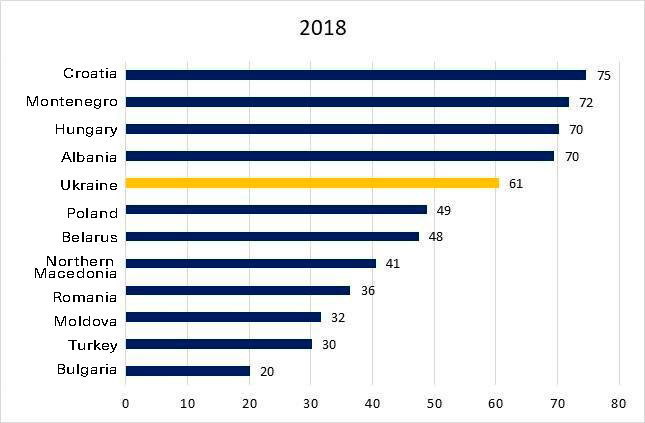

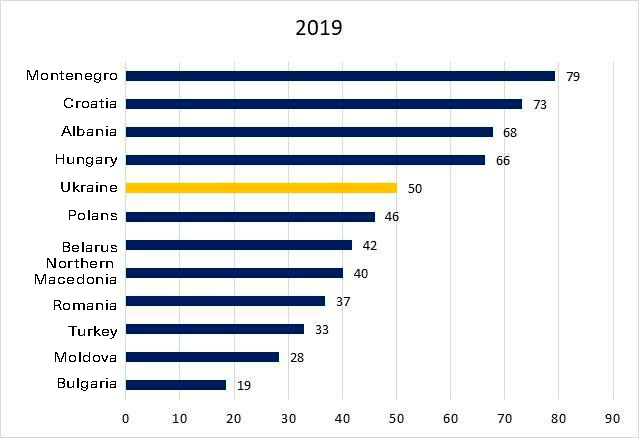

Thus, Ukrainian debt was 60% of GDP at the end of 2018, and this was not the lowest value among a group of similar countries (see Figure 2). At the end of 2019, public debt fell to 50% of GDP, and this is also not the lowest figure.

Figure 2. The ratio of the public debt to GDP in the developing European countries

The IMF data

The Minister does not state the amount “taking into account the shadow sector” of public debt. However, only official GDP (partly the shadow sector is taken into account in official statistics) is used to calculate the ratio of public debt to GDP, because the shadow sector estimates are very inaccurate. For example, for Ukraine they range from 30% to 50% of GDP. So, to talk about a low level of debt “taking into account the shadow sector” and at the same time to assess the rest of the countries according to the official data, is a manipulation.

Indeed, in 2019, 11% of budget expenditures were spent on debt service. Recently, IGLBs with a maturity of more than 1 year are sold with a yield of about 11%. Therefore, the Minister correctly named the cost of debt service. The high cost of debt is due to inflation expectations and high credit risks of the country.

In addition, it is not enough to look only at the ratio of the public debt to GDP. It is also necessary to take into account the currency structure and composition of debt holders. In Ukraine, as of August 2020, 67% of public debt is denominated in foreign currency. This carries currency risks, that is, the devaluation of hryvnia will automatically increase the debt-to-GDP ratio. Besides, a significant share of public debt is held by state-owned banks. Therefore, further growth of the budget deficit may create the effect of crowding out investment. That is, banks will invest in IGLBs instead of lending to the real sector.

According to the interview, the Minister understands this and suggests two ways to “reduce the attractiveness of IGLBs”: the reduction of the reserve requirements of the NBU and liberalization of the capital movements (which has already taken place). However, for some reason Mr. Petrashko starts talking in a negative way about foreign investors who bought a large amount of Ukrainian IGLBs in 2019 (in principle, the purchase of IGLBs by foreigners leads to an influx of foreign currency bought by the NBU and thus provides Ukrainian banks with more funds that they can invest in the real sector).

False

“Approximately $5 billion entered the IGLBs. We understand, we are all smart people, that this is a short-term investment. We understand that this money came in a speculative way, but we must understand that it will be taken away. This is not an investor, we must understand this. It was necessary to redeem everything in reserves. They were redeemed, but somewhere around 2.5-3 billion were redeemed. Because of this there was a speculative growth of hryvnia. Because it is not an investment. If it’s an investment, you may not redeem it.”

The volume of IGLBs in the portfolio of non-residents really increased in 2019 by $5 billion (from 6.3 to 115.8 billion UAH). But at the same time in 2019, the NBU bought $ 7.9 billion, and not $2.5-3 billion. That is, the NBU bought even more currency than what came from non-residents in IGLBs.

The vast majority of bonds purchased by foreigners were for a period of more than 1 year, i.e. medium-term ones (the report, Fig. 2.6.5). It is very difficult to withdraw these investments quickly due to the illiquidity of the secondary market. Simply put, there is no one to sell the IGLBs bought by foreigners to.

In addition, the issuance of IGLBs “equalizes” the debt structure – reduces the share of external debt in its total. Therefore, the Ministry of Finance’s choice of IGLBs, rather than Eurobonds, is to be welcomed.

Strengthening of the national currency is natural for countries that reduce inflation (inflation targeting provides a floating exchange rate). Short-term negative effects are offset by long-term positive effects on the economic growth. For example, a stronger hryvnia makes imports cheaper. This creates favorable conditions for investing in production capacity, as almost all equipment of Ukrainian companies is imported. And also it forces the domestic manufacturer to compete with cheaper imports. That is, consumers benefit from it.

From Petrashko’s quote, it is clear that he does not consider the purchase of IGLBs as an investment. Obviously, the term “investment” for him stands for a foreign direct investment. However, this is wrong. Investments are both investments in Ukrainian securities and the purchase of physical assets. It is not clear why currency should not be redeemed when buying physical assets. After all, a person who wants, for example, to buy a plant in Ukraine, must also exchange their dollars or euros for hryvnias. Same as a person, who wants to buy IGLBs.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations