Since the onset of the pandemic, there has been a lot of information about COVID-19, both true and false or manipulative. We conducted our own online survey and found that people tend to assess their own awareness about the disease and compliance with quarantine measures comparing to others. Those who consider themselves to be in better health and those getting information mainly from small, local sources such as Telegram channels are less informed about the coronavirus.

2020 was marked by the global spread of not only SARS-CoV-2 but also of information on how to protect against it, often misinformed. Some theories kept replacing others with lightning speed while fact-checkers and the media often failed to verify their authenticity. The World Health Organization even introduced a new concept, “infodemic” – to denote the rapid spread of both true and false information in society.

Although it was quite natural to believe unverified information that was often harmful to the health during the first months of the pandemic, the myths we still continue to believe in one year after quarantine can be a threat to the effective curbing of the virus within the country and globally. This is especially true given the recently launched vaccination program.

There are more than two hundred thousand scientific articles published on the topic of Covid-19 today. Official briefings are often given by the WHO and statements made by experienced doctors are widely disseminated in the media and social networks. Yet what makes a large part of society stubbornly continue to believe in the miraculous power of ginger to fight the disease? We tried to explore these and other issues in the context of behavioral economics to understand how our cognitive biases affect perceptions of measures aimed at preventing disease spread.

To this end, we conducted an online survey via social networks to assess whether respondents were aware of the facts about the pandemic and vaccination. We also asked respondents to self-evaluate in terms of how aware and responsible they think they are with regard to their compliance with quarantine regulations. Similar questions were asked about their relatives, acquaintances and the country’s population as a whole.

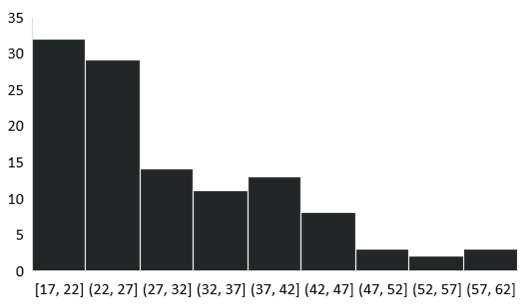

The questions were answered by 184 people, mostly from the three regions of the country – Lviv, Kyiv and Odesa. The sample comprises 70% of those aged 18 to 35 (Figure 1), with 31% of them being men employed in both private and public sectors, as well as students at local universities. Although our sample cannot be considered representative, it makes it possible to identify important trends in making daily decisions on how to behave safely i.e. decisions that ultimately determine our ability to collectively confront the pandemic.

Figure 1. Respondents’ age distribution

Source: own survey

Our study found that 33% of respondents take vitamins to combat the coronavirus, 17% believe that ginger, garlic or turmeric can enhance protection against the disease, 14% believe that moderate alcohol consumption has the same effect, with another 11% taking antivirals. At the same time, more than half of respondents are not aware that vaccination is effective against different virus strains and 42% believe that the vaccine “infects” us with the active virus first, and only then allows us to produce antibodies. Although it is hard to call our knowledge about preventive measures and vaccination perfect, most respondents acknowledge that it is more important for them to decide on how to protect themselves based on their own beliefs than to follow measures implemented by local or central governments. For more details, see below.

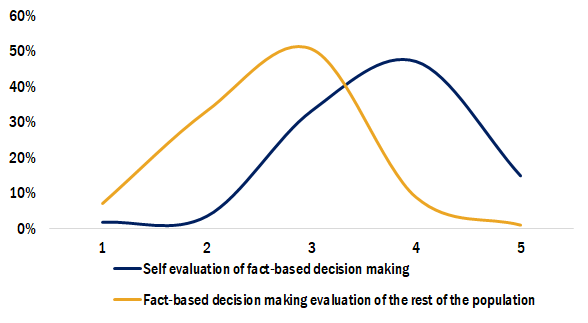

The first observation concerns how people assess their own awareness compared to the rest of the country’s population. Nearly all respondents indicated that their own awareness of the facts was an order of magnitude higher than the rationality of the rest of the population (Figure 2). Although the average value of individual awareness is 4 on a scale from 1 to 5, with 5 being the highest awareness level, the corresponding average value for the rest of society is slightly less than three. Behavioral economics explains this phenomenon by the naive realism, or “third party” effect. According to the bias, a person tends to overestimate the impact of information messages on others compared to themselves. Simply put, it seems to us that we are “the smartest in the room”. People believe that they are seeing the world objectively, while others, especially those that disagree with them, are poorly informed or irrational.

Figure 2. Respondents’ evaluation of the extent to which their own behavior (blue line) and other people’s behavior (yellow line) is fact-based

Source: own survey

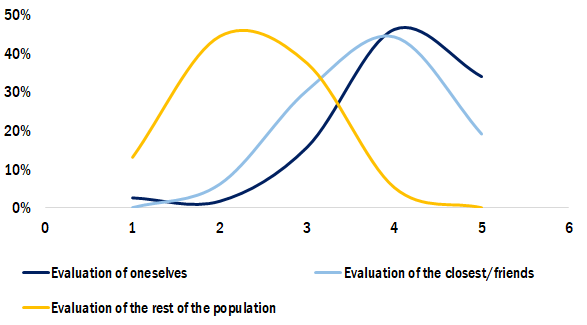

We obtained similar results for the question about compliance with quarantine regulations. On average, respondents evaluate their own responsibility for compliance with quarantine measures at almost four and a half (on a scale from 1 to 5), with the corresponding evaluation of the rest of the population being only slightly more than two (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Evaluation of compliance with quarantine regulations: respondents (blue line), their close relatives and friends (blue line) and other people (yellow line).

Source: own survey

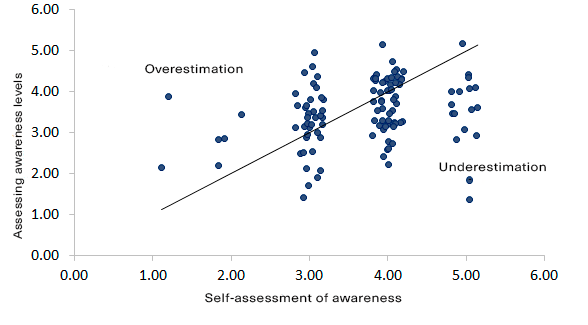

Based on responses to the 13 questions about popular myths associated with vaccination and preventive measures (e.g. vaccines “infecting” us with the virus first; masks causing oxygen toxicity; at least 10 minutes necessary to get infected when in close contact), we created an index of respondents’ awareness of the facts. The index’s values range from 1 to 5 and it is based on the number of correct answers to the 13 questions. Comparing our respondents’ awareness index with their self-assessment of awareness of the facts, we can confirm another behavioral economics bias, namely the Dunning-Kruger effect. This popular cognitive bias states that those not up to speed on the facts very often overestimate their knowledge, while better informed people are prone to underestimating themselves.

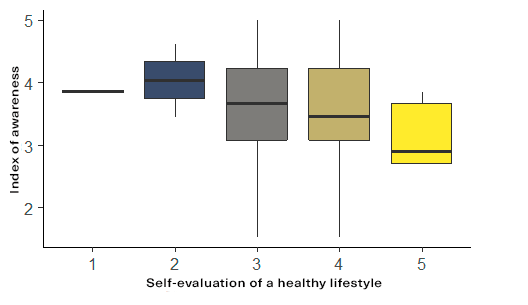

Within our sample, those who consider themselves aware of the “coronavirus” facts, did poorly to assess the veracity of popular myths. The correlation coefficient between self-assessment of their awareness and actual awareness is only 0.24. At the same time, those who provided more correct answers underestimate their ability to rely on facts when making decisions about the pandemic. Accordingly, the more we know, the more we understand that our knowledge is limited (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Self-assessment of awareness of the coronavirus (horizontal axis) and assessment of awareness based on respondents’ answers about the “coronavirus” facts

Source: own survey

Interestingly, even after receiving information about new knowledge in the field of pandemic prevention measures, people mostly remain true to their previous, often erroneous beliefs.

Thus, those with a higher awareness index generally acknowledge the increasing effectiveness of measures used to treat and prevent disease today as compared to last year. On the other hand, respondents with a lower awareness index according to our assessment are more prone to believing that the authorities and scientists are hiding information for profit reasons and that the ways of combating the disease have not improved. This can be explained by the “Conservatism bias”. If someone formed their understanding of certain remedies at the beginning of the pandemic, it is harder for them to accept new information on this issue given the large variety of such information, much less so to change their mind.

Another interesting result is that those who better assess their own health are less aware of the “coronavirus” facts (Figure 5). This can be explained by the fact that those leading a healthy lifestyle believe they can come through the coronavirus disease easily if they get it, and therefore do not care too much about learning more about the disease and appropriate safety measures.

Figure 5. Self-evaluation of a healthy lifestyle and the index of awareness of the “coronavirus” facts

Source: own survey

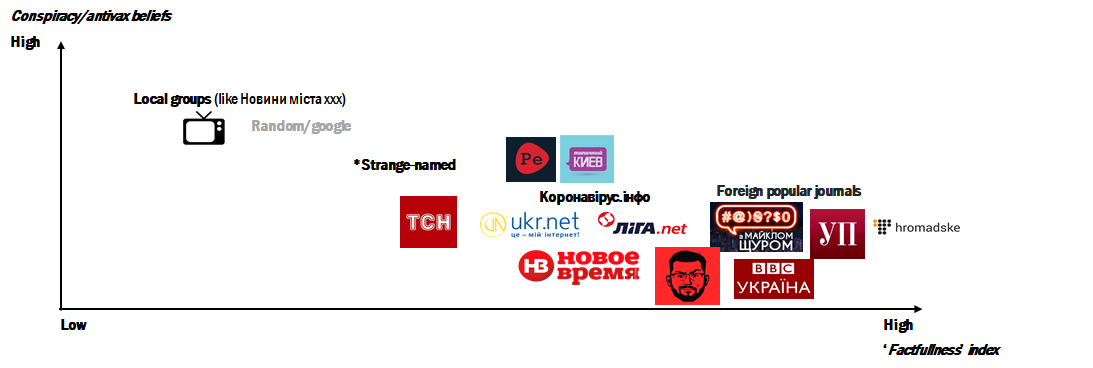

There is no sure way to tell what makes us believe in certain myths. For example, we also examined the influence of the media on the value of the index of awareness and found that those using Instagram as one of their two main sources of information have an average of 0.45 percentage points below the index value (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Main news sources, conspiracy or anti-vaccination beliefs, and the index of awareness

*’bagriova news’, ‘khrinovyny’, ‘Baba i kit’, ‘Meduza’, ‘Perepichka news’, ‘Looking for in Kyiv’ etc. Only those news sources that were mentioned more than 2-3 times are taken into account

Source: own survey

Also, those least aware of the facts and those showing considerable faith in conspiracy theories mostly get information from TV programs, random news stories in their browser or small news channels on social networks delivering mostly entertaining content. The situation is similar with the residents of small towns, whose awareness index value is on average lower.

Our survey showed that even those most confident about their own rationality often fall hostage to a cognitive bias. The first step to overcoming it is to realize that we all occasionally make mistakes, and that other people may know more than we do. There is no simple recipe for the virus: ginger cannot save us from disease, while critical thinking very well might.

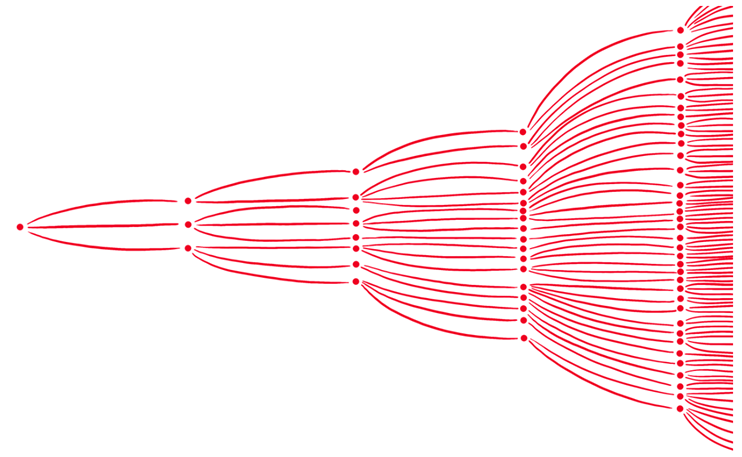

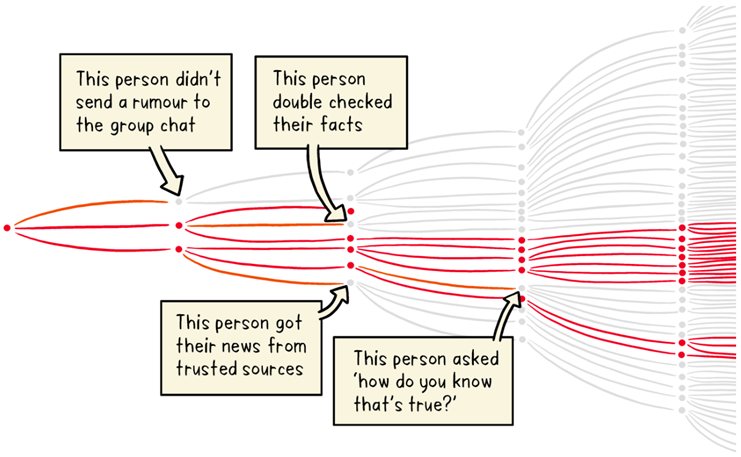

And although official communication regarding the spread of and protection against the virus and vaccination is very important, first off, we need to understand that each of us is a separate link in the spread of “infodemic”. And if one person does not spread rumors in a group chat, while another one cross-checks information using alternative sources, with a third one inquiring about what this or that statement is based on, it is possible that our collective awareness will grow over time.

Figure 7a. False information spreads like a virus

Figure 7b. However, we can considerably slow down its spread

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations